As the spread of Covid-19 grips the world, health officials on the African continent have called for help for essential supplies such as masks and ventilators. While some are trying to fill the physical gap, a grassroots effort to get out the information on how to prevent the virus -- washing hands, keeping a distance from others, coughing into your elbow -- has been effective in communicating vital information.

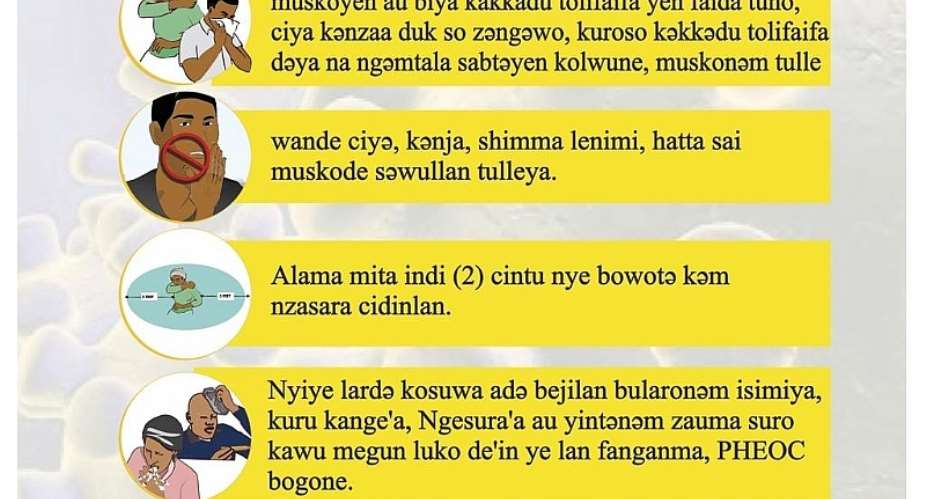

Journalists, filmmakers, graphic designers, and those who can speak or write effectively in one of the estimated 3,000 local languages on the African continent have mobilized to get the message out on how to prevent the deadly virus that is spread by breath droplets as they are coughed or sneezed. Coronavirus can also be transmitted when a person touches their face after touching a contaminated surface. The virus can be absorbed through mucus membranes.

While some governments and health ministries have launched local language information, journalists like Elia Ntali and Kudzanai Gerede, who both work for the Harare-based Zimbabwe newswire 263Chat, translated information on Covid-19 in Shona and Ndebele, respectively.

For Gerede, a business journalist originally from Bulawayo, it was second nature to get the information out in Ndebele, a local language spoken by many who feel marginalized in the south of the country.

“Very few people think about translating information into Ndebele,” Gerede tells RFI. He put forward the idea to write stories in Shona and Ndebele during an editorial meeting where journalists were discussing how to make the Covid-19 information as clear as possible for their audience.

“I suggested to do a write up in Ndebele and asked my other colleague if he could do the same in Shona. The editor liked it and then we just took a government statement written in English and paraphrased it in local languages since we realised there wasn't any literature in these languages,” he says.

Although he grew up speaking Ndebele, he said that he had to think about how to translate words such as quarantine and social distancing.

“Of course, that was a little challenging, but it wasn't that difficult because the language is broad, there are words that also mean the same as distancing oneself from others,” the journalist says. “I managed to put it across the best way possible, using phrases to describe one word,” he adds.

The news portal received good feedback in more ways than one.

“I'm happy to say a few days later I saw government also trying to do the same in indigenous languages,” says Gerede, adding that they also received positive feedback on their WhatsApp groups.

In DRC, from Ebola to Corona

The eastern Democratic Republic of Congo discharged its last Ebola patient nearly one month ago, and now local health educators are trying to bring communities up to speed on how to protect themselves from coronavirus. Confusion about the similarities and differences between Ebola and Covid-19 is rife, says Laure Venier, a community engagement program coordinator for the DRC with Translators Without Borders (TWB).

“A lot of people are expressing that they feel safer because they know how to take care of themselves because of the hygiene measures put in place for Ebola,” she tells RFI.

Vernier says that rumors have already begun that this is another disease intended to make money. During Ebola, some Congolese believed that the fatal hemorraghic fever was created for international non-governmental organisations to make money.

“That's a really sad aspect and we need to communicate about this. I think the good thing would be do it openly and honestly,” she says. Ensuring that people have the vital information in their own language will stem the spread of misinformation. Venier says that rumors such as drinking tea will prevent Covid-19 has been flagged in TWB media monitoring, and the misinformation such as the tea cure is spreading internationally, too.

The Congolese authorities have created a helpline in nine different local languages that is open from 8h00 to 20h00, which Venier says is useful, acknowledging that creating a helpline in all 400 local languages would be a near-impossible task.

Nigerian solidarity

While Nigeria is trying to deal with how to maintain social distancing and put food on the table, a number of people as well as UN agencies have come together in order to get the word out in some of the local languages in Africa's most populous country.

Nigerian filmmaker Niyi Akinmolayan, famous in his own right for directing The Wedding Party 2, the highest-grossing Nollywood movie of all time, used his skills to create a short video that he then dubbed into a number of Nigerian languages, including Igbo, Pidgin and Hausa. Akinmolayan has been promoting them on social media to ensure everyone knows about how easily Covid-19 is spread.

The United Nations, which usually operates in six official languages, has expanded their public information campaigns to include posters in Hausa, Kanuri, Yoruba, and Igbo, and have included a misinformation feature as well.

One woman produced a video in Fulfulde, a language spoken by the Fulani people mainly in Adamawa state in Nigeria, in addition to two northern provinces of Cameroon. The video was shared on the US Embassy in Yaoundé's Facebook page.

Information is available across the length of the continent

South Africa is tackling misinformation regarding Covid-19 by running a WhatsApp helpline in five of the country's 11 official languages—English, Sotho, Zulu, Xhosa and Afrikaans. South Africa's News24 reported that although the helpline initially only took questions in English, the Health Department added four more to accommodate more South Africans.

It has also created a number of videos, including this one in Zulu.

In Morocco, it was the initiative of yet another journalist, Hammou Hasnoui, and graphic designer Aissam El Nehali who created a video with subtitles in Tachelhit and Tarifit, two Moroccan Tamazight (also known as Berber) dialects. They have posted their videos on Youtube and Facebook in order to get the word out to the Berber minority in the country.

Information needed for African refugees based in Europe

Many on the continent have answered the call to get information out, but groups who work with refugees and asylum seekers in Europe are also working to ensure the most vulnerable understand how the disease is spread.

The Linguistic and Intercultural Mediations in a context of International Migrations group (LIMINAL), has already asked online for help in translating coronavirus information into a number of languages, including 15 African local languages. A member of the group told RFI that they have already had translations into Sudanese Arabic and Tigrinya, a language spoken in Ethiopia and Eritrea.

The British site for medical charity Doctors of the World has information translated into a number of languages, including Somali and Tigrinya.

French residents have had to print out and carry an authorization to leave their homes. For refugees who do not speak French, the Anti-Authoritarian Group for Toulouse and its Surroundings (IAATA) has translated the French guidelines and has provided the authorization letter in a number of languages, including Amharic, Bambara, Diakhanke, Igbo, Malagasy, Peul, Soninke, Sussu, and Tigrinya.

Ireland's national health service has also translated Covid-19 guidelines into a number of languages, including Yoruba.

Lay KPMG audit report on SML-GRA contract before Parliament – Isaac Adongo tells...

Lay KPMG audit report on SML-GRA contract before Parliament – Isaac Adongo tells...

Supervisor remanded for stabbing businessman with broken bottle and screwdriver

Supervisor remanded for stabbing businessman with broken bottle and screwdriver

NDC watching EC and NPP closely on Returning Officer recruitment — Omane Boamah

NDC watching EC and NPP closely on Returning Officer recruitment — Omane Boamah

Your decision to contest for president again is pathetic – Annoh-Dompreh blasts ...

Your decision to contest for president again is pathetic – Annoh-Dompreh blasts ...

Election 2024: Security agencies ready to keep peace and secure the country — IG...

Election 2024: Security agencies ready to keep peace and secure the country — IG...

People no longer place value in public basic schools; new uniforms, painting wil...

People no longer place value in public basic schools; new uniforms, painting wil...

'Comedian' Paul Adom Otchere needs help – Sulemana Braimah

'Comedian' Paul Adom Otchere needs help – Sulemana Braimah

Ejisu by-election: Only 33% of voters can be swayed by inducement — Global InfoA...

Ejisu by-election: Only 33% of voters can be swayed by inducement — Global InfoA...

Minority will expose the beneficial owners of SML, recover funds paid to company...

Minority will expose the beneficial owners of SML, recover funds paid to company...

Prof. Opoku-Agyemang has ‘decapitated’ the NPP’s strategies; don’t take them ser...

Prof. Opoku-Agyemang has ‘decapitated’ the NPP’s strategies; don’t take them ser...