In our weather calendar, Uganda has two seasons: wet season and dry season. However, with the increasingly erratic weather conditions engendered by climate change, can we still proudly stand and swear it is wet or dry season?

Whether it’s our weather bureau forecasting or just a layman predicting, rains can come today or a dry season can last months!

The month of August 2016 is ending today. I am walking down a dusty road branching off a tarmac road stretching to Mbale, that Eastern Ugandan district once home to banana and coffee production. It is not a stranger passing the same road since this is my own county, but for the first time since I am a man, I am witnessing a strange dry spell.

The bus drops me at the edge of a village of my destination. Down the bend, begins a landscape of fields of unhealthy crops with seared pale leaves wilting in the hot weather. A bare land on my distance is conspicuously gleaming with heat as though there’s fire underground.

Rains normally came in plenty between March and April and between August and October often in the greater part of the country with exception to semi-arid areas like Karamoja region in the far north, but this dry spell is puzzling to even the meteorological department.

In the country where agriculture employs 85% of the population, and 95% of farm outputs is directly dependent on natural weather, rain is worshiped and treasured.

Every country man like me has in the head, an imaginary chip of calendar marked with dry season months, wet season months and cold and hotter days but is mine getting corrupt and distorted by a natural ego to find a tranquiller hamlet?

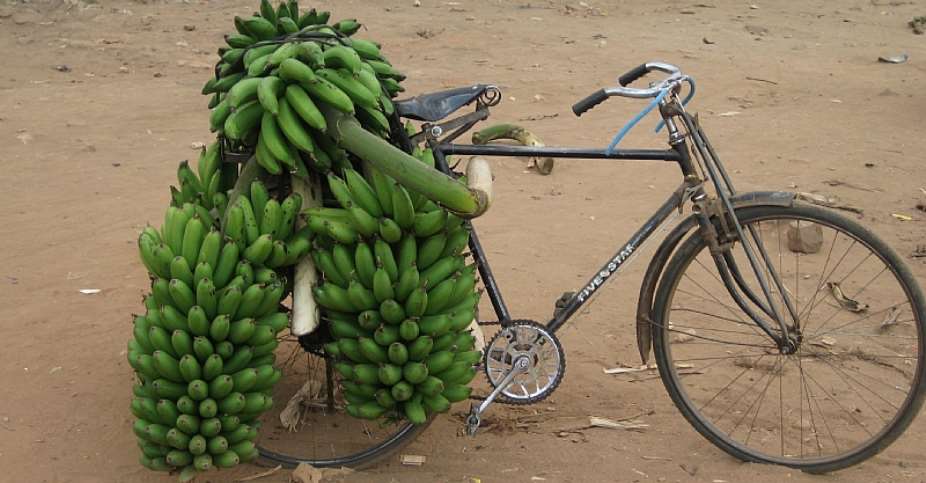

The first man I am meeting sloping downhill rolls a superannuated bicycle loaded with five bunches of banana. He calls me son because he knows I am born of the locality despite that looking for greener pastures elsewhere sometimes keeps us away from one another. He is Mr. Masaba, going in his banana trade.

Masaba: “Son, glad to see you, have visited this village with too much sun”

Me: “Father, I hope to eat a lot of Matooke and take some dry coffee beans with me.”

Masaba: “See for yourself.” He said as he jumped aside to take a look at the small bunches on his bike “these bunches look smaller from what is normal. There has never been a drop of rain two months in a row. No one knows what’s happening these days.”

I could have told Mr. Masaba that all is strange is the impacts of climate change. But that would have been too much for a layman to take. Instead, I simplified the sentence and said: the world is changing.

This is how local people phrase climate change, because yes, they see changes but they cannot see the hidden triggers behind these changes.

The most visible feature of these changes is the poor farm output, for the fact that most local farmers let alone peasants cannot afford improved farming techniques such as irrigation.

Widely known is the fact that after planting, you must keep your fingers crossed lest hot-spells should invade. But seldom does nature answer these prayers in full request. Along the path of crop husbandry, the manifestations of the ‘evil’ of climate change torments from sowing to harvesting.

First, there is a wide-spread banana disease called ‘weevil’ alongside coffee borer beetle. The two are allies of a warmer environment.

Secondly, warmer weather stiffens soils making it difficult to weed. What usually happen is that labour stays redundant humbly waiting for rains to come before drudgery can resume.

Then finally that strong wind that usually blow down acres of banana trees, another appalling curse causing wretchedness among farmers.

Such, have always often surrendered Uganda to the hands of food handouts from the World Food Programme. Between 2007 and 2009, northern Uganda was hit by what is known to be “the worst hunger in 60 years” which reverberated throughout the region, extending to South-Sudan, Ethiopia and Somalia. Over 4000 perished and more than 60,000 wandered for food and water.

These sayings make it obvious that “water is life”. But this is wrong. The Ugandans insist water is life to only those who have never drowned in floods. Those who have experience the ordeals of floods curse heavy downpours with the same might as dry days.

So when it’s too dry, it is deadly. When it is too wet, it is deathly.

And yet these are the very extremes the threats of climate change purports to touch—so threatening to food and economic security as we have seen.

To alter the above fates, urgent mitigation and adaptation actions should be taken to contour global efforts in curbing carbon-dioxide emissions, the source of all the troubles. Only by this can we will restore the natural order of our planet to outwit unpredictable weather conditions.

Written by Boaz Opio

'Kill whoever will rig Ejisu by-election' – Independent Candidate supporters inv...

'Kill whoever will rig Ejisu by-election' – Independent Candidate supporters inv...

Ashanti Region: ‘Apologize to me for claiming I owe electricity bills else... – ...

Ashanti Region: ‘Apologize to me for claiming I owe electricity bills else... – ...

Ghana is a mess; citizens will stand for their party even if they’re dying — Kof...

Ghana is a mess; citizens will stand for their party even if they’re dying — Kof...

Internet shutdown an abuse of human rights — CSOs to gov't

Internet shutdown an abuse of human rights — CSOs to gov't

Free SHS policy: Eating Tom Brown in the morning, afternoon, evening will be a t...

Free SHS policy: Eating Tom Brown in the morning, afternoon, evening will be a t...

Dumsor: A British energy expert 'lied' Ghanaians, causing us to abandon energy p...

Dumsor: A British energy expert 'lied' Ghanaians, causing us to abandon energy p...

What a speech! — Imani Africa boss reacts to Prof. Opoku Agyemang’s presentation

What a speech! — Imani Africa boss reacts to Prof. Opoku Agyemang’s presentation

Dumsor: Tell us the truth — Atik Mohammed to ECG

Dumsor: Tell us the truth — Atik Mohammed to ECG

Dumsor: Don't rush to demand timetable; the problem may be temporary — Atik Moha...

Dumsor: Don't rush to demand timetable; the problem may be temporary — Atik Moha...

Space X Starlink’s satellite broadband approved in Ghana — NCA

Space X Starlink’s satellite broadband approved in Ghana — NCA