“With the exception of Nigeria, Brazil is the country with the largest African population in the world. It is therefore not only strange but also scandalous that such a country defines itself only through a Eurocentric model, for the final objective of the Eurocentric ideology is the elimination of African descendants: a type of subtle and hypocritical genocide which does not leave any traces of its crime”. Abdias do Nascimento, Orishas: The Living Gods of Africa in Brazil.

My interest in Brazil goes back many years. I have always been intrigued and fascinated by the huge castles the Europeans built on the West Coast of Africa especially those at Elmina and Cape Coast, in Ghana. These massive structures were built first for trading in gold, spices and later, for the nefarious slave trade. I always wanted to know where the millions of persons they took from Africa finally ended.

Elmina Castle (O castelo São Jorge da Mina) was built by the Portuguese in 1482. Other castles built by the Portuguese were: Forte de São Antonio (1503, Axim), Forte São Sebastião (1520, Shama) and Forte de São Francisco Xavier (1640). Other Europeans also came to Ghana (then Gold Coast) Brandenburger (Germans), French, Swedish, Danes, Dutch and, of course, the British.

The Portuguese were in Ghana from 1470 until 1637 when they were defeated by the Dutch.

I also got to know or hear about a lot of persons with Portuguese names, such as Olympio, D'Almeida, Da Costa, Da Silva, De Souza, Dos Santos, who were very much at home in West Africa. These persons who are called “Brazilians” in Ghana, Togo, Benin and Nigeria had relatives in Brazil and were the descendants of Africans who returned from Brazil, especially in 1830's after the government there had turned against Africans and was making life impossible for them. They were accused of being the ring leaders of the various slave revolts which shook Brazil in that period, especially the Male revolts.

I am therefore not the first African to go to Brazil but I believe I am one of the very few who have travelled there to see how the Africans there are faring. The first Africans, as we know, went to Brazil under the inhuman conditions of slavery. The traumatic journey across the Atlantic and the terrible fate they met in Brazil are well known. Are their descendents now enjoying better conditions than those that made some of their ancestors flee Brazil? Do they now enjoy full freedom? Do they still experience racial discrimination? These were some of the questions I asked myself before embarking on this journey which was an educational journey. A journey of emotions because the suffering of other Africans in slavery and colonialism affects us even today. Europeans may not understand that the continuing racial discrimination and obvious injustice suffered by persons because of their colour affects all those with the same or similar skin-colour, no matter their social condition or country of origin.

Our original plan was to go directly to Bahia which is the most African of Brazilian cities but our Brazilian friends advised us that one could not visit Brazil without seeing Rio de Janeiro, the most beautiful city. So Rio became for us a station on the way to Bahia.

RIO DE JANEIRO, A STOP ON THE WAY TO BAHIA

We arrived at Rio de Janeiro on 4 November, 2006 after a very long journey of several hours, Frankfurt - Sao Paulo-Rio. But our discomfort was surely nothing compared to our brothers and sisters who were abducted and sent across the ocean. Chained, rowing, without much food or drink, they made their way in the dirty ships with the whips of their masters ensuring that they never relaxed. We were rather lucky to be flying in a modern aircraft with friendly and helpful flight personnel.

We drove from the airport to our hotel, right in the middle of Copacabana. What a breath-taking view from our hotel! I have never seen a place like the Copacabana beach. The street, Avenida Atlantica, with its wavy black and white patterns by the famous landscape architect, Burle Marx, is itself an art work. From our hotel we had a fantastic and clear view of the Sugar Loaf Mountain (O Pão do Açúcar) which is one of the main symbols of Rio, after the Statute of Christ the Redeemer (O Cristo Redentor).

We visited many museums: Museum of Fine Arts (Museu das Belas Artes), Museum of Modern Art (Museu da Arte Moderna) a post-modern construction which is situated in a very extensive and beautiful park, Flamingo Park (O Parque do Flamingo). Another impressive sight was the Metropolitan Cathedral (O Catedral Metropolitana), a conic structure soaring into heaven. The most impressive of all the buildings we saw was the Museum of Contemporary Art (O Museu da Arte Contemporanea) at Niteroi, a few kilometres from Rio. As one approaches the museum, one sees arising, as it were, from the sea a structure looking more like an UFO.

This building was designed by the most famous Brazilian architect, Oscar Niemeyer who is hundred years old. I believe that if the architect had constructed only this building in his entire career, he would have earned his place in the history of world architecture. Neither before nor after our visit to Brazil have I seen any building as imposing and as ultra modern as the Museum of Contemporary Art at Niteroi.

We also visited the Botanical Garden (O Jardim Botánico) in Rio. What a vegetal explosion of colours! Many of the tropical plants were known to me since we have them also in West Africa but nowhere did the plants appear to be as alive as in Rio. The Botanical Garden seemed to have all that is beautiful in a tropical climate.

Another interesting place was the Sambódromo, a huge structure with capacity for 40,000 constructed by Oscar Niemeyer. Here is the climax of the Carnival where all the various groups must present themselves before a jury that decides which is the best group. There is also a Carnival museum where one can admire the costumes of previous carnivals.

Rio de Janeiro is indeed a marvellous city, “Cidade Maravilhosa” but after ten days of visiting various places and enjoying the hospitality of the “Cariocas”, as the inhabitants of this wonderful city are called, we decided to move on to our main destination: Bahia.

BAHIA, BAHIA, BAHIA

The arrival in São Salvador de Bahia de Todos Santos (Saviour Saint of the Bay of All Saints) on 14 November 2006 was in itself a source of profound satisfaction and spiritual contentment. I felt I had at last reached the destination of most of the brothers and sisters who were dragged across the Atlantic, against their will to unknown destinations by those greedy nations who are now very busy preaching human rights to the rest of the world. They are loud in their magnificent orations about human liberty and dignity but they are the very first to do violence to human beings. I had heard so much about Bahia in connection with the Brazilians or African Brazilians who returned to West Africa. Moreover, the novels of Jorge Amado had also made us familiar with many places in Sao Salvador. I felt I knew Bahia even before going there.

The writings of Abdias do Nacsimento had also revealed the real existential problems of the African Brazilians in facing discrimination in a land which even denied the existence of such discrimination.

Contrary to the advice of our travel agency, we insisted on staying in a hotel in the Pelourinho, the old city, the historical centre in order to be close to all the places of historical importance and to be able to visit places of interest on foot.

The name “Pelourinho,” pillory, is actually the name of the place where slaves were openly punished, mostly whipped by their masters in order to show their power and authority and as example to others. The Portuguese slave masters decided to erect the pillory right in the centre of the city, in the very large open space where the Casa Jorge Amado is now located.

AFRO-BRAZILIAN RELIGIONS

In the Pelourinho, I felt I could hear the cries and tears of the African slaves who must have been asking themselves what sins they had committed for God to place them in the lamentable and painful situation they were in; they were asking why the others, the Portuguese, human beings like themselves were causing them immense suffering and unbearable pains without any obvious justification. The cries and lamentations of the African slaves were often so loud and noisy that the Catholic churches demanded that the punishments should be administered in other places and not so close to the churches. The loud cries prevented the churches from concentrating or continuing their services. The contradictions between Catholic theology of love and the nefarious practice of slavery could not have been more patent than in São Salvador, in the Bay of All Saints.

It appears that the African deities assisted the African slaves in their travail on the other side of the Atlantic. Evidently, the orisas crossed the Atlantic Ocean without too much damage. The African slaves kept their religions but had experienced much difficulty in their religious practice in view of the massive repression of their masters and the Catholic Church. To avoid unwanted external control, the slaves adopted the names of Catholic saints for African deities and thereby created a mixed religion, candomble which now has many followers in Brazil, including many whites or people of Portuguese origin. Another such African-Brazilian religion is the “umbanda” which has also several adherents of all races. The African-Brazilian religions constitute the second religious force in Brazil, after the Catholic Church.

Brazilians seem to be very religious. In any case, there are numerous churches and religious festivities in Brazil. Some of their churches were designed by well-known architects such as Oscar Niemeyer whilst many more were built in the colonial days by the Portuguese. We had the impression that there were more churches in Salvador da Bahia than in the rest of the world. It is often said that there are in Salvador at least 365 churches, one for every day of the year: Catederal Basilica, São Pedro dos Clerigo, Igreja São Domingos de Gusmao, Igreja e Convento de São Francisco (which is filled with gold plated walls and altars) Igreja Nossa Senhora do Rosario dos Pretos (built by the Africans because the whites did not accept the presence of the blacks in their churches), Igreja de Nosso Senhor do Bonfim.

A few minutes after our arrival in São Salvador, we started visiting all the important places of the old city which is built on hills. We visited the Casa Jorge Amado (Jorge Amado Foundation) which is right in the middle of the Pelourinho. Many of the works of the great Bahian and Brazilian author are found in the house. The building is very modest and we had the impression that neither the Brazilian government or the Bahian government wanted to invest much resources and efforts in the memory of the most important Brazilian and Lusophone author whom most people thought should have been awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature. We were really not prepared for this small and somewhat modest house after all the big and extremely interesting architecture we had seen in Rio de Janeiro. In any case, we were very disappointed to see what little importance was attached to the man who made Bahia and Brazil better know by the rest of the world. Next to the Casa Jorge Amado, on the left, is the Museu da Cidade (The Municipal Museum) which is really not worth visiting. You learn very little about the development of the city in this museum. They did not even have paintings or drawings on the development and changes of the various parts of the city over the centuries. Hardly any information on the population of the city throughout the ages. Naturally, they had no catalogue or booklet which a visitor could take home and read.

Not far from the Pelourhino, is the Praça Terreira de Jesus where the Museu-Afro-Brasileiro (Afro-Brazilian Museum) and the Igreja Sao Francisco are located.

The Museu Afro-Brasileiro has many objects from Africa and tries to depict the material and spiritual life of Africans and Bahians but it is evident that the museum does not have the resources necessary for its ambitious task. In the same building is an Archaeological and Ethnological Museum where one can see a few pre-colonial and colonial artefacts and the cultural patrimony of the indigenous people of Bahia and Brazil. But in general there is little information about the Indios and other peoples who lived in Bahia before colonization. The most impressive items in the museum are the wooden panels of the orisas by Carybe, depicting each orisa with his arms and his liturgical animal.

After visiting these museums with little resources, we went to another which had all one would expect: The Carlos Costa Pinto Museum. Already, the exterior of the building, the perfectly mowed green surroundings suggested that we were entering a mansion of the rich. The interior confirmed the promises and expectations of the exterior. Gold and silver objects, impressive oil paintings showed that this museum was in a different category from what we had so far seen.

The museum is in a big bourgeois mansion, with a marvellous garden and a fountain. The collection of a rich Bahian who died in 1946 shows the incredible wealth which the colonizers and slave masters accumulated in the New World. There are porcelain plates and figures imported from China and Japan. The tea service was imported from France and other items from Great Britain and Germany.

We also visited Solar da Unhão, a huge complex which had several facilities, including an exhibition hall. We saw in this complex, an Afro-Brazilian show on orishas, capoera and other African dances. Brazilians are excellent organizers and gave us a perfect show even though many aspects of the representation was simplified for the benefit of tourists who cannot be expected to understand within a short evening the whole sophistication and complexity of Yoruba cosmology. The orisas, African gods, were completely simplified.

Before the show, we ate a sumptuous meal in the same restaurant where the show was going to take place. There is no doubt that Afro-Brazilian cuisine is one of the best in the world. It is basically African food, modified with certain European and Brazilian elements and ideas. We ate more in Brazil than we normally do in Europe because of the good quality. It is difficult to resist when presented with tropical fruits, bananas, plantains, coconuts, cassava, yams and a variety of fish. This type of meal is clearly not for those who want to lose weight! Brazilian coffee has been known for centuries as one of the best and we could verify that it even tastes better in Brazil.

We also saw on 15 November, an exhibition of African masks entitled “Playing Masks” (“Mascaradas que tocam”) by Emilia Biancardi, with the assistance of a school of dance (“Escola de Dança da Fundação Cultural”). This scenic exhibition was constructed on the basis of studies of elements, symbols and masks of different African nations recreated with sounds played by the bodies of the dancers.

A very interesting construction in Salvador de Bahia is the “Elevador Lacerda”, the Lift, which at the Praça Tome de Souza, links the old city with the new city. Constructed in 1930, some 72 meters high, this construction allows one to do in five minutes a distance which could take about a half an a hour on foot.

After an intensive occupation with cultural matters, we left the city to visit the beaches in the region. We took the route in direction of the green line for the northwest of Salvador, with the aim of visiting, “Mangue Seco”, (Dried Mangrove). What an enchanted view all around. I have never seen any beaches as beautiful as those in this area.

PIERRE VERGER.

Before leaving Salvador, we visited the “Fundação Pierre Verger “ (Pierre Verger Foundation). Pierre Verger was a Frenchman who devoted his life to African culture and especially, to African religion of voodoo and the history of slavery between Brazil and Africa. He spent 17 years in West Africa and came to Salvador de Bahia where he stayed for fifty years until his death. (2) We were very well received at the Fundation by its officials who explained to us their work in organizing the legacy of the writings, photos and films of Verger who seems to have been working all the time.Veger was not only a scholar of African religions and culture but also a photographer who travelled in many parts of Africa, Asia and Latin America.

Verger wrote many books on African culture, religion and slavery, the best know being, Flux and Reflux of the Slave Traffic between the Benin Gulf and the Todos os Santos Bay (1976) .( Fluxo e Refluxo do Trafico de escravos entre o golfo de Benin e Bahia de Todos os Santos(1987)). The followers of candomble, the Afro-Brazilian religion, have great respect and affection for this extraordinary man who along with Carybe and Jorge Amado, is regarded as one the pillars of culture in Bahia. Verger was a friend of Carybé, Amado and Gilberto Gil.

CARYBÉ

Carybé was illustrator, ceramist, sculptor, muralist, historian, researcher, painter and journalist. His father was Argentinean but his mother was Brazilian. He settled in Salvador after some years of working as a journalist for an Argentinean newspaper and contributed in making Bahia a region well-known in the world for its religious and mythical character. He produced some 5000 pieces of work and illustrated books by Jorge Amado and by Pierre Verger. His 27 wooden panels representing the African gods, orisas of candomble, are in the Afro-Brazilian Museum in Salvador. Carybé had the honorific title of Oba de Xango and died of heart attack during a session of candomble.

AFRO-BRAZILIAN DANCE AND MUSIC.

As one can imagine, we heard a lot of music in Rio and in Salvador. Brazilian music is known all over the world, especially the so-called Música Popular Brasileira (MPB), made popular by Gilberto Gil, Jobim, Buarque and others. There is a wide variety of music, such as bossa nova, funk, reggae, samba reggae, jazz samba, samba rock, batuca, forro, maracatu, repentismo, frevo, carimbo, bumba-meu boi, pagoda and others which have no equivalent elsewhere. Brazilian funk seems to consist in using a few words and a simple rhythm but repeating it to death.

We heard many groups of musician rehearsing in the historic centre of Salvador da Bahia but we often had the impression that the music, especially the sound of the drums, was just too loud in the hot climate. We also visited the group Oludum which was celebrating its thirtieth anniversary as a group. As you may know, most of the musicians of MPB come from Bahia, especially Salvador - João Gilberto, Caetano Veloso, Maria Bethânia, Gilberto Gil (once a Minister for Culture) Magareth Menezes, Daniela Mercury, Carlinhos Brown and Gal Costa are some of the musicans from Bahia, the most African state in Brazil. Of course, there are musicians from other states and cities - Antonio Carlos Jobim, is a Carioca (name for a person from Rio) who with a Bahian guitarist, João Gilberto composed pieces such as the Girl from Ipanema. These two muscicians are considered as the creators of bossa nova.

It is with pleasure and a feeling of pride for an African to realize that African music and dance have contributed tremendously to Brazilian culture. We felt at home in much of the music and dances we experienced. A strong and intensive re-africanization is noticeable in the music and dance of groups such as Oludum, Ile Aiyê, Banda Dida, Are Ketu, Malê Debalê and other groups called Blocos Afros, that in cooperation with Afoxes,(cultural associations, that work with the candombles), try to achieve the recognition and identification of their past and the African legacy of Brazilians. Many of the musical instruments that the Brazilians use are of African origin, for example, agogo, atabaque. We could enjoy much of this culture without difficulty and with much fraternal emotion. It appears that wherever Africans were sent in slavery, a new and strong culture developed.

CAPOEIRA

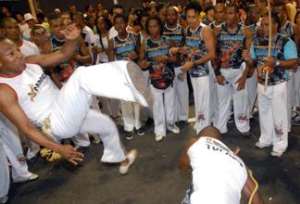

As most readers know, Brazil is well-known for capoeira, an Afro-Brazilian martial art, a mixture of dance and struggle accompanied by music and part of the African culture which is very evident in Brazil and above all, in Salvador da Bahia. Music is an integral part of capoeira and most of the instruments used are of African origin. We saw many groups of young capoeristas training at public places in Salvador, especially in areas where tourists were present. This dance/fight was developed by African slaves in Brazil in order to resist their white oppressors. The physical agility and speed required for the various bodily movements are just astonishing and are not recommended for those who have no previous training!

Capoeira was viewed previously as a subversive activity punishable by a law of 1890, a year after the abolition of slavery in Brazil. Repression and imprisonment of capoeristas continued until 1941 when it was recognized as a sporting activity. Today capoeira is practised in the whole world and there are associations of capoeiristas in many countries. This dance/struggle sport brings many tourists to Brazil and especially to Bahia.

FAVELAS

What can one say about favelas, those ghettos of the poor? These places which frighten even the police who do not dare to enter that part of the town without fear? Violence, drugs and criminality rule in the favelas. There are some 700 favelas in Rio de Janeiro with a population of 3 million inhabitants. Most of the houses have neither potable water nor electricity and families with four or five children could be found in very small rooms. But the favelas are places of much artistic creativity. Many musicians, painters and other creative black artists live there in incredible conditions. The famous Carnival of Rio survives mainly because of the contributions of the samba schools that exist in the favelas. In Rio, the favelas are not very far from the beautiful residential areas of the rich. There is only a short walking distance between the favelas and rich areas such as Ipanema, Lapa and Copacabana.

What kind of world is this? The authorities cannot control certain parts of the town and this has been going on for decades. What a shame! In reality, one has the impression that the presence of a majority blacks and other poor people in these areas explains the attitude of the Brazilian government. Somebody should explain how a people that can construct some of the most beautiful buildings in the world with magnificent gardens cannot manage to solve the question of the favelas. It appears to be a conscious political attitude.

In many countries it is evident that the houses of the poor, what the French call ”maisons de fortune” are temporary constructions of variable dimensions but in Brazil one has the impression that these houses are built according to established norms and that these constructions are not going to disappear so soon. They are accepted as integral parts of social structures and will not change. This is a very depressing perspective.

RACISM

Brazil is a magnificent country with very friendly people but there are few things which surprised me. There exists a very subtle racism which does not show itself but an experienced observer cannot fail to notice racial discrimination in the country. If you ask a Brazilian whether there is racism in the country, he or she would certainly reply that there is no such thing there. But how is it that the better jobs are all in the hands of the whites and the blacks have the menial jobs? Even in the most African of Brazilian cities, Salvador da Bahia, we did not see black persons at bank counters. If there was a black employee at a bank, he was either a security personnel or a cleaner. Besides, the majority of blacks live in favelas. In general blacks earn half of what the whites earn. How should one describe this situation if not as racism? Many Brazilian say they have African blood but this does not excuse or justify the racial discrimination we observed. Certainly, the Brazilians do not practice the kind of racism you meet in the United States or in some European cities. In public life, we had the impression from time to time that there were no blacks in the country. They do not take part in some public activities. For example, in museums you hardly see any black visitors. The same goes for the theatres or cultural activities unless the blacks are musicians or actors or officially participating.

What also surprised us is the way people looked at us. Everywhere we went, people seemed surprised, if not shocked, to see an African with a European lady. In museums and restaurants people appeared to be more interested in us than in the exhibition or in the food. This behaviour was certainly a reflection of the social reality of Brazil or at least the parts in Rio and Salvador we visited. It became evident for us that it is not normal in Brazil for blacks and whites to move together. We seldom saw mixed couples. The white women went with white men, the black men went with black women and women of mixed parentage went with men of mixed parentage. In the twenty days we were in Brazil, we hardly saw any interracial couple. The mixing of races seems to have taken place long ago.

But most Brazilians say they have African blood. This is true but it does not explain or justify the kind of subtle racism we think we saw in Rio and Salvador.

We were also surprised at the way people dressed in Rio, especially around Copacabana: tight tee-shirts and Bermuda shorts. This was alright for the slim persons but the fat ones were quite noticeable. Many women seem to feel obliged to show parts of their bodies. We were often confronted with women who seemed under some compulsion to show whatever they had.

On the whole Brazil is worth visiting and certainly one of the most beautiful countries of the world. An African in Brazil, especially, in Salvador will feel much at home and would also realize what our countries could be like in the future. He would also notice that the Brazilians always keep time. There is no such thing as Brazilian time. During all the time we were there no one was ever late. Exhibitions opened on time. Drivers arrived at expected time. Offices opened at the indicated time.

We left Brazil with the feeling that, except for the favelas and the subtle racial discrimination, the country had everything one would wish for and that when the Brazilians say that God is a Brazilian, they are probably not very far from the truth. About how many other countries can one say that? Nature has been extremely generous in this part of the world.

Kwame Opoku, 23 August, 2008.

|  |

|  |

|  |

|  |

| |

| View All | |

NOTES

(1) “O Brasil se constitui no maior país negro do mundo, excluindo-se somente a Nigéria. Não só é estranho como também escandaloso o fato do país se definir pelo padrão eurocentrista, pois o objetivo final dessa ideologia é a

extinção do descendente africano: uma espécie sutil e hipocritica de genocídio que não deixa as marcas do seu crime.” Abdias do Nascimento, Orixás: Os deuses vivos da África 1995, p. 33 IPEAFRO/Afrodiaspora, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

Abdias do Nascimento,economist, writer, dramatist, poet, painter, actor, emeritus university professor, founder of the Museum of Black Art in Rio de Janeiro in 1968, founder of the Black Experimental Theatre (TEM) in 1944, was born in March 1914. He was the first Black senator in the Brazilian Federal Parliament in 1995. Abdias do Nascimento has written several books and articles on racial discrimination in Brazil and spent sometime under the military dictatorship in Brazil. He has been since his infancy an activist in the fight against racial discrimination in Brazil. See also, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Abdias_do_Nascimento; “Abdias do Nascimento: The Only Brazilian I'm Proud Of !” http://www.verinhaottoni.com/abdiasdonascimento/texts/bio.html

http://www.abdias.com.br/ excellent site; see also “ Brazil: The Cult of Whiteness”, where Nascimento declares, inter alia,

“Race and colour discrimination is one of the most important factors of unemployment, and racial income and employment inequalities are a well-established fact of Brazilian life.

Brazilian ruling society still adheres to the theory that racial inequalities are a function merely of class barriers. Yet we exist as Africans and as Africans we are excluded, this is the indisputable fact. Because of our African origin, we suffer endless limitations at the collective, personal and spiritual levels.”

New African, No433, October 2004. http://findarticles.com

(2) See also “O Bresil de Pierre Verger” http://www.youtube.com

'Kill whoever will rig Ejisu by-election' – Independent Candidate supporters inv...

'Kill whoever will rig Ejisu by-election' – Independent Candidate supporters inv...

Ashanti Region: ‘Apologize to me for claiming I owe electricity bills else... – ...

Ashanti Region: ‘Apologize to me for claiming I owe electricity bills else... – ...

Ghana is a mess; citizens will stand for their party even if they’re dying — Kof...

Ghana is a mess; citizens will stand for their party even if they’re dying — Kof...

Internet shutdown an abuse of human rights — CSOs to gov't

Internet shutdown an abuse of human rights — CSOs to gov't

Free SHS policy: Eating Tom Brown in the morning, afternoon, evening will be a t...

Free SHS policy: Eating Tom Brown in the morning, afternoon, evening will be a t...

Dumsor: A British energy expert 'lied' Ghanaians, causing us to abandon energy p...

Dumsor: A British energy expert 'lied' Ghanaians, causing us to abandon energy p...

What a speech! — Imani Africa boss reacts to Prof. Opoku Agyemang’s presentation

What a speech! — Imani Africa boss reacts to Prof. Opoku Agyemang’s presentation

Dumsor: Tell us the truth — Atik Mohammed to ECG

Dumsor: Tell us the truth — Atik Mohammed to ECG

Dumsor: Don't rush to demand timetable; the problem may be temporary — Atik Moha...

Dumsor: Don't rush to demand timetable; the problem may be temporary — Atik Moha...

Space X Starlink’s satellite broadband approved in Ghana — NCA

Space X Starlink’s satellite broadband approved in Ghana — NCA