‘African art, like any great art, some would say, in any case, more than any other, and for a long time if not always, is first of all in man, in the emotion of man transmitted to objects by man and his society.

This is the reason one cannot separate the problems of the fate of African art from the fate of the African man, which is to say the fate of Africa itself.’ - Aimé Césaire, Discours sur l’art africain,1966. (1)

The recent lull in the restitution of African artefacts has left a vacuum filled with activities that, although not directly anti-restitution, do not directly promote restitution.

After the restitutions of 2021 and 2022, few restitutions seem to have taken place in 2023, mainly due to the ‘shocked’ reaction of Cambridge and Oxford universities, which refused to sign agreements with Nigeria on the Benin bronzes, alleging their surprise and dismay at the decree of the then-outgoing President Mohammadu Buhari affirming the ownership of the Oba of Benin in the Benin artefacts returned to Nigeria. Using their alleged shock at the President’s affirmation of the long-established fact of the ownership and guardianship of the Oba, the two institutions and others alleged that their understanding was that a new museum would keep the returned artefacts. Other people in Germany, Britain, and France cried foul, claiming a breach of promise by Nigeria. Meanwhile, the then-Director-General of the Nigerian National Commission on Museums and Monuments said he was awaiting clarifications and instructions from his government. (2) The alleged vacuum left by inactivity was filled, among other things, by a newspaper alleging waning public interest in restitution. (3)

We then heard experts suggest we should de-emphasize the violence in colonial acquisition methods and concentrate on the new relationship between the restituted objects and those remaining in Western museums. But are violence and robbery not the very essence of colonialism and imperialism? Can we discuss the restitution of Benin artefacts without examining the horrendous British attack on Benin City in 1897? Can we understand the implications of restituting Namibian artefacts without discussing the cruel and brutal extinction order of Lothar von Trotha, the German commander who wanted to wipe out the Herero and ordered that all Herero, man, woman, or child, with or without arms, should be exterminated? Can one fully understand the restitution of Congolese artefacts by Belgium without some idea of the ruthless regime of the brutal King Leopold II, whose exploits will make many sick? The Western acquisitions of the precious treasures of African peoples has been a story of great violence and destruction. Accounts of colonialism are accounts of the violence that facilitated robbery of cultural artefacts among other objects.

Michel Leiris and other writers have documented abundantly the connection between colonial acquisition methods and cultural artefacts in the Western world. Afrique Fantôme does not deal with ghosts but with violent colonial acquisition of African cultural artefacts that are now in Musée du Quai Branly, Paris. (4)

We should note that during the period that may appear as a time of inactivity on the restitution front, Fowler Museum, Los Angeles, returned to the Asantehene in Kumase, Ghana, seven of the gold treasures that the British had looted in their invasion of Kumase in 1874. The Los Angeles Museum may soon restitute other African artefacts. At about the same time, the British Museum and the Victoria and Albert Museum unashamedly announced they would be returning to Ghana thirty-two items from the notorious British invasion of Kumase on loan for three years, described in British museum language as long-term loans. (5) Did Fanon not warn us in The Wretched of the Earth that the colonised people must realise that colonialism never gives anything away for nothing.?

Looted artefacts were also recently restituted to the Lebang people in Cameroon.

I was surprised when I read about a seminar called’ Exhibiting Difficult Histories: Benin Objects and their Potential for New Forms of Representation. The announcement declares boldly, ‘The recent dynamics around restitution and the transfer of ownership have resulted and continue to result in new ways of presenting Benin works. On the occasion of launching a newly curated part of the Benin exhibition in the Humboldt Forum, this panel focuses on the display of Benin objects in current exhibitions and their potential for new forms of representation. We bring together case studies from different museums in Germany, Britain, the US, and Nigeria, all of which deal with the objects they house from their very own situatedness.

Together with our guests, we investigate museum strategies of exhibiting: Which forms of representation do they adopt to historicize the collections? How do they aim to incorporate a polyphony of voices in their exhibitions? Which role does modern and contemporary art play in newly curated Benin exhibitions?’ (6)

What are the organizers of this symposium trying to achieve?

The Benin artefacts still need to be fully restituted, and some scholars are already thinking about what other representation they could signify other than that they represent the culture of the Benin (Edo) people. Any other alleged significance or representation before the West returns the artefacts in large numbers could only be a diversion from apparent facts and should not be encouraged. They are jumping into the post-restitution period before we have reached there, so it may not even be necessary to get there.

What difference does it make to the people of Benin to know what Felix Luschan and other Europeans said about the reception of the Benin artefacts in Europe? Whether they considered the Benin artefacts as evidence of a highly civilized African culture or proof of a low level of development does not detract from the fact that the British savagely attacked Benin in 1897, stole about five thousand artefacts, and refused to return them. The British Museum, where the bulk of the artefacts are, is still unwilling to talk about the return of the objects or the repair of the injustice caused by a European power that took advantage of the weakness of an African kingdom and robbed its cultural treasures, thus putting an end to a kingdom, culture, and civilization that had been in existence since the 11th century. The same imperialist violent invasions had taken place in China in 1860, Ethiopia in 1868, Asante in 1874, and Benin in 1897, with the resulting massive transfer of wealth on display in Western museums. Do these scholars and curators want the Benin people’s illegally and illegitimately acquired treasures returned or not?

Scholars should be more concerned with the violent destruction involved in the notorious attacks and the possible restitution and compensation rather than seek to provide post facto justifications that inevitably result in diverting attention from the moral and material deficiencies that these notorious attacks reveal, and the continuing injustice involved. But the real danger in the above-mentioned approach became clear when we read the following:

‘Two additional showcases will expand the process-based Benin exhibition. While the first part of the exhibition focuses the restitution debates and Benin’s art history, the two new showcases will broaden the perspective on the kingdom. Among other things, they show how pre-colonial entanglements—in particular, the trade in enslaved people—still have an impact on the latest restitution debates. (7)

It seems from the above quotation that the Humboldt Forum is giving some weight to the view that looted Benin artefacts should not be returned to the Oba because of Benin’s alleged role in the Transatlantic slave trade; the objects should remain in the Western museums where they are now.

Those espousing such a view seem to ignore the crucial role of the Great Britain, France, Germany, Holland, Norway, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, and the United States in the notorious crime against humanity. We do not need to lecture anybody on the infamous trade that involved Europeans and Africans, but to recall a few salient points. The victims of this inhumane trade that brought at least twelve million people from Africa to North America, mainly to the USA, and to South America, mainly to Brazil, were Africans; those who benefited most from the notorious trade were primarily Britain, France, Germany, Holland, Spain, Portugal, and the United States. (8)

The Industrial Revolution in the Western World would not have been possible without the massive transfer of material wealth from America and Africa and the cheap labor provided by the slave trade. Marine transport, insurance, and banking systems were all primarily developed through the slave trade. Prof. Kehinde Andrews rightly states:

“The entire Western economic system depended on the wealth from slavery. That wealth remains with us to this day, as does the poverty created through the brutal system. We think of slavery as belonging to the distant past, but the world we live in remains created in its image.’’ (9)

The blame for slavery cannot, therefore, be placed solely on Africans. Given the preceding points, how can anybody suggest that Benin artefacts looted by the British army should be left in Britain, France, Germany, Holland, and the United States but not returned to Benin because Benin participated in the transatlantic slave trade? Are the European and United States less guilty of this inhumanity than the Benin Kingdom?

Does the Humboldt Forum, via the Prussian Cultural Foundation, to whom Nigeria has lent many Benin artefacts, not have a duty to observe a minimum respect for facts concerning Benin and Nigeria?

Would the Humboldt Forum give credence or weight to a theory that suggested that victims of Nazi confiscations were themselves involved in the infamous transatlantic trade and, therefore, not entitled to recover objects seized from them by the Nazi criminals?

We should observe that in such cases, one is making Great Britain or Germany a judge in their case. In the matter of slavery, Western States have no moral or legal standing to determine that looted African treasures should stay in their countries because of African participation in the notorious trade.

The hurry to find new representations of the Benin artefacts reminds one of the speed of colonial missionaries in baptizing African children as soon as they reached missionary premises and in giving them Christian names to replace African names, thus giving them new significance of their birth.

The Humboldt Forum building, built at the location of a former palace of slave traders, with the pompous golden cross fixed atop its dome and its pseudo-biblical citation, is a Christian premise despite attempts by Monica Grütters, former German Culture Minister of Germany, to play down the symbolic significance of the Christian cross, which the widow of a German capitalist had financed. (10) Would the Humboldt Forum encourage the discussion of the role of the Hohenzollerns in the slave trade and Germany’s contribution to the sordid business? Suppose we accept participation in the slave trade as a ground for depriving Benin of its rights to its looted artefacts. Should we not use participation in colonization as grounds for taking away rights to artefacts and other property? Colonization, with all its horrible massacres and genocides in the Congo, Namibia, Kenya, Tanzania, South Africa, and Algeria, was also a crime against humanity, as even French President Macron admitted. (11)

If we sanction Benin for participation in the slave trade, we must sanction all other states or peoples, including Westerners, who participated in the horrendous business or benefitted from this cruel trade

After all this, one might realize that the best solution to the issue of looted artefacts would be to return them to those who produced them, as Amadou Mokhtar M’Mbow suggested in 1978. (12)

The Nigerian-German arrangements on restitution of looted Benin artefacts are in several memoranda of understanding and agreements, which have not all been published and are not likely to be released soon to the public. When I asked those who should know, I was informed the documents were not available to the public.

Those agreements that have been published, such as the Agreement on the Return of Benin Bronzes between the Stiftung Preussischer Kulturbesitz and the Federal Republic of Nigeria, dated August 25, 2022, revealed very favourable provisions for Germany. (13) For example, Section 3, Liability Clauses, provides as follows:

(1) In consideration of the Foundation’s transfer of ownership of the objects to Nigeria, Nigeria hereby releases, acquits, and forever discharges the Foundation and the Federal Republic of Germany from any and all liability for all claims, demands, damages, actions, causes of action, or suits at law or in equity, of whatsoever kind or nature, which Nigeria had, has, or may in the future have arising from or relating to the Foundation’s possession of the objects prior to the date of this agreement and the return of the objects to Nigeria pursuant to this agreement

.

(2) In addition, Nigeria shall not hold the Foundation and the Federal Republic of Germany liable for any third-party claims involving the objects, especially claims based on ownership or possession, as well as corresponding claims for damages.

This very extensive exemption clause frees Germany and the Prussian Cultural Foundation from all liability based on the Benin bronzes, whether related to damages to the objects or the deprivation of their use by Nigerians for over a hundred years. Effectively, this clause will defeat any claims of compensation. Did the Oba and his advisers see such a clause, and were they asked for their assent or consent? Was the document ever presented to the Nigerian government, apart from the National Commission on Museums and Monuments? If such a clause becomes the standard in future agreements between African States and Western museums relating to restitution, then we can abandon any hope of receiving compensation of any kind for the hundred years of deprivation we have experienced. As a matter of justice, we have demanded, in our writings and talks, compensation for the loss of use of our artefacts and damages resulting from the violent attacks and removals of the artefacts. (14)

It comes as a surprise to realize that in our days when everybody is crying out for transparency in matters of public interest, museums are allowed to hide agreements relating to artefacts. Section II of the agreement of August 25, 2022, between Nigeria and Germany, entitled Transition and Loan, Subject Matter, provides

that ‘Upon the passing of title to the objects, Nigeria shall grant the Foundation the possession and use of the objects listed in

Appendices 1 (objects to be returned to Nigeria in the short term) and 2 (objects that will remain on loan) are free of charge. These appendices have not been published. How do we know which objects are being loaned to Germany?

The suggestion for a clear break between the period of illegal detention of Benin artefacts and legal possession from the date of the agreement has not been accepted. We also suggested that, for a stated period, the artefacts that have been away for more than a hundred years would return home to enable Nigerians to see them and that, for a limited period, Western museums should not exhibit Benin artefacts. It appears indecent to organize an exhibition of Benin artefacts ostensibly for the last time before they are returned and to see them still in the same museum a week later. Shame and decency are not qualities prevailing in some places.

The speculation on what significance the Benin artefacts can have other than representing Benin culture has only become relevant since Nigeria loaned many precious treasures to Germany and other Western museums that had previously refused even to discuss the possibility of restitution. They feel emboldened to claim other representation from the looted/loaned artefacts. Would they have speculated on different representations of the Benin artefacts if they did not now legitimately have a considerable number in their collection? Indeed, some of the finest Benin artefacts are still in Western museums. (15)

Shall we hear in the future that Benin artefacts must remain in Germany or elsewhere in the Western world because they are necessary for educational purposes? Shall we also hear that the admiration and appreciation of Benin objects are part of the culture of educated Germans? (16)

Eventually, the search for another representation of the Benin bronzes, other than representing Benin culture, would end in another version of the theory of the universal museum, which Western theoreticians and museums have not entirely abandoned. Even some Westerners who support African restitution think that African artefacts are rightly held in Western museums. Some African artists and scholars do not see what is wrong with the present situation. Funds for research on the restitution of African artefacts at present comes only from Western sources that may have no interest in an independent African view which challenges the hegemony of Western scholars and museum officials.(17)

We should note that the universal museum concept survives in different forms. It may be presented as ’retain and explain policy’,’ but it is part of our history.’ Has anyone ever heard a thief, or his accomplices insist on holding onto stolen goods as part of their history? Should we allow bank robbers to hold on to their stolen millions as part of their history instead of returning them? Western museums have grown used to keeping thousands of stolen artefacts of other peoples, being assured by some ethnologists that they have thereby saved the objects from perdition.

The museums have often served as handmaidens of imperialist governments, born at the height of imperialism or, if preferred, born in the European Enlightenment, which established a scale of human development with Europeans on top and Africans at the bottom.

The current revival of ideas of the universal museum coincides with recent attempts at recolonization, whereby the former colonial masters seek to dictate directly to former colonies the forms of their social organizations and warn about the forfeiture of aid assistance while fomenting attempts to destabilize weaker states, alleging violations of human rights in the African States whilst they themselves are actively violating the human rights of Africans through the cruel Western immigration policies. The violations of the human right to culture appear unknown to these avid supporters of human rights. The extreme right and liberals seem united in their brazen interference in the affairs of former colonies, which we did not see even in the heydays of Western imperialism.

The search for other representations of the Benin artefacts is preparing the ground for future contentions and disputes about what was agreed upon by Germany and Nigeria in their agreements. Germany has an established record for preserving documents and other objects, and one can imagine future disputes and their resolution. German cultural heritage will be extended to cover treasures looted from Africa that have been in Germany for hundreds of years. If the experience with the restitution of artefacts looted by Napoleon is anything to go by, Benin children may never see the bust of Queen-mother Idia that is at present in the Humboldt Forum, Berlin, Germany. Some artefacts looted by Napoleon and his invading army in Belgium, Italy, and Germany are still in the Louvre in Paris, France.

We should remember that the British Museum has not restituted any artefact, alleging that this is not allowed by the British Museum Act 1963. We have shown in many articles that this is not true if one looks at the text of the law as opposed to the policy of the venerable museum. While welcoming the museum’s new director after the theft scandal that shook confidence in the museum, we do not expect much change concerning looted artefacts. The museum will only propose loans to the owners of stolen looted artefacts, as it has offered to the King of Asante.

France restituted twenty-six artefacts to the Republic of Benin in 2021 and has since not returned any looted artefacts, although it is busy reforming the law. However, the Sanchez Report appears to be an announcement of the burial of African artefacts in France. The French still keep the statue of the God of war, Gou (Benin Republic), in Musée du Quai Branly-Jacques Chirac, the British Museum, continues to keep the famous ivory hip mask of Queen-mother Idia Benin, Nigeria. At the same time, the Germans still hold the bust of Queen-mother Idia in the Humboldt Forum. We could extend the list of African icons that Western museums are keeping, some with the consent of African governments. Did they realize what the game was about?

Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Holland, Italy, Norway, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, and Portugal have not made any concrete restitution of African artefacts.

Westerners show their greatest contempt for Africans on the question of looted artefacts, where the colonial mentality still reigns unchallenged. How can the British Museum and the Victoria and Albert Museum offer a loan of thirty-two artefacts to the Asante owners from the thousands of artefacts that the British stole from the Asante in the various invasions? When Nigeria loaned Benin artefacts to Germany and other States, they were for ten years and automatically renewable unless there were objections from one party.

Many seminars and other activities are held to create the impression that Africans are associated with activities of Western museums, but they tend to minimize the evident disparities between former colonies and the Western States and thus legitimise indirectly existing power differentials without addressing this issue.

Hardly had any looted African artefacts been restituted when discussions started on the fate of the restituted objects, resuming old arguments and questions. Could Africans look after their cultural artefacts? Are these artefacts open to public view ? Are they in private palaces of kings such as the Oba of Benin, now considered or degraded by many to a private person. They thus display their limited knowledge about Benin and African kingship generally. Western scholars appear thus more interested in the fate of the few restituted objects more than the thousands of African treasures still in Western museums and institutions.

The motive for the reluctance of Western museums to restitute looted artefacts is clear. They are determined to keep their control on the fate and narrative of African/Benin history and art history. The quest for other representation and multi-perspectivity (an ugly word) clearly shows a desire to deny the Benin people the sole control over the narrative of their history. Benin interpretation of their art and culture would be one among many other views and there could be no claim to exclusivity. Benin scholars and people would have to admit the validity of other interpretations of Benin culture.

Did we ever hear Africans and Asians dispute with Europeans about the interpretation and representation of European art? Could European art represent any culture other than European culture?

Westerners are determined to keep their control and hegemony over African art. They are using all means, including provenance research, to re-assert their control over African art.

Plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose. (The more it changes, the more it is the same.)

The intransigence of Western museums and States on the issue of restitution of looted African artefacts will lead many Africans, especially the youth to consider new ways of resolving the matter, seeing that their elders are not finding acceptable solutions. The methods of the elegant and eloquent Mwazulu Diyabanza, not approved by all, signify only the beginning of such rethinking. The youth born after Independence do not have the inhibitions, complexes and complicities of earlier generations and are thus, able to act, free of neo-colonialist restraints, with only the interests of their people in mind.

NOTES

1.Aimé Césaire, Discours prononcé par Aimé Césaire à Dakar le 6 avril 1966 », Gradhiva [En ligne], 10 | 2009,

https://www.erudit.org/fr/revues/etudlitt/1973-v6-n1-etudlitt2193/500270ar/

2. K. Opoku, ‘Does Affirmation of the Rights of the Oba in Benin Artefacts Confuse some Western Museums?’ https://www.modernghana.com/news/1227999/does-affirmation-of-the-rights-of-the-oba-in-benin.html

3. Restitution, Reparation Efforts See Halting Progress Across Europe and the US, amid Shifts in Public Opinion,https://www.artnews.com/art-news/news/restitution-repatriation-art-efforts-europe-united-states-progress-1234696438/

4. Michel Leiris, Afrique fantôme, 1934, Gallimard, Paris. Phantom Africa by Michel Leiris, translated by Brent Hayes Edwards, Seagull Books, 2017.

With this excellent English translation of Afrique Fantôme ,English readers have now the possibility to appreciate the significance of the historic book by Leiris. Anyone interested in the restitution of African artefacts or colonialism will do well to read this major work, which is available also in German, Portuguese, Spanish and Italian.

See also K. Opoku, https://www.no-humboldt21.de/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/Opoku-MacronPromisesRestitution.pdf

The literature on colonial violence is enormous and we can only mention a few publications here:

Dierk Walter, Colonial Violence: European Empires and the Use of Force,2016, Oxford University Press.

Lauren Benton, They Called It Peace: Worlds of Imperial Violence, 2024, Princeton University Press Toyin Falola, Colonialism and Violence in Nigeria, 2009, Indiana University Press, Caroline Elkins, Legacy of Violence: a History of the British Empire, 2023,Vintage.

5. K. Opoku, ‘British Museum and Victoria and Albert Museum Loan Looted Asante Artefacts to Asante /Ghana: Where Is The Morality?’ https://www.modernghana.com/news/1295729/british-museum-and-victoria-and-albert-museum-loan.html

7. Exhibiting Difficult Histories, ibid.

8. Aimé Césaire has rightly proclaimed:

And I say to myself, Bordeaux, Nantes, Liverpool, and New York and San Francisco not an inch of this world devoid of my fingerprint, my calcaneus on the spines of skyscrapers, and my filth in the glitter of gems!

Who can boast of being better off than I am?

Virginia, Georgia, and Alabama Monstrous putrefaction of revolts stymied, marshes of putrid blood trumpets absurdly muted Red, sanguineous, consanguineous land.

Notebook of a Return to the Native Land ... by Aimé Césaire, translated by Clayton Eshleman & Annette Smith

https://susa-literatura.eus/kaierakm/aime-cesaire-cahier_d'un_retour_au_pays_natal.pdf

9. Prof. Kehinde Andrews rightly states:

“The entire Western economic system depended on the wealth from slavery. That wealth remains with us to this day, as does the poverty created through the brutal system. We think of slavery as belonging to the distant past, but the world we live in remains created in its image.’’

The New Age of Empire: How Racism and Colonialism Still Rule the World, Penguin Books, 2021, p.57.

10. K. Opoku, Golden Cross On Humboldt Forum : Arrogance, Stubborness, Provocation And Defiance.

https://www.modernghana.com/news/1013271/golden-cross-on-humboldt-forum-arrogance-stubbor.html

11. Macron admits that colonization was a crime against humanity

Will Macron's new commission face up to all of France's colonial atrocities?

12. A Plea for the return of an irreplaceable cultural heritage to those who created it: an appeal by Mr. Amadou-Mahtar M'Bow, Director-General of UNESCO

https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000046054)

13. Agreement on the Return of Benin Bronzes between the Stiftung Preussischer Kulturbesitz and the Federal Republic of Nigeria, 25 August 2022.

14. African Art Award Honoring Dr. Kwame Opoku,

https://dia.org/events/margaret-herz-demant-african-art-award-honoring-dr-kwame-tua-opoku

https://www.modernghana.com/video/1/394741/

15. Digital Benin, https://digitalbenin.org/

16. During a debate on the Parthenon Marbles in the British House of Lords in connection with an amendment of the British Museum Act 1963 Lord Eccles declared:

‘I salute the ancient Greeks for their wonderful history, but the Greeks of the 20TH Century should know that we, too, have a history. Part of our history is expressed in our admiration for their art. We should not open the door to political campaigns for the return of works fairly acquired and now splendidly cared for.’

See Hansard, British Museum Act 1963(Amendment) Bill Hl, Volume 444: debated on Thursday 27 October 1983, cited in Jeanette Greenfield, The Return of Cultural Treasures, Third Edition, 2007, p.107.

The comment of Lord Eccles is praise for ancient Greeks and a defiant challenge to modern Greeks. He praises the culture of the ancient Greece and challenges the present Greeks to deny what he takes as established that the British are also successors to that magnificent culture and denies to modern

Greeks any claim to exclusivity of ownership of the achievements of the old culture, including the Parthenon Marbles which the British saved from destruction in Athens, and which are now perfectly preserved in the British Museum. They would have been destroyed in Athens if Lord Elgin had not saved them from the terrible conditions in Athens.

This British argument is similar to that of James Cuno that the present Egyptians are different from the ancient Egyptians who created ancient Egyptian civilization. They do not eat the same food, follow the same religion, and wear the same clothes as the ancient Egyptians.

See K. Opoku, Do Present-Day Egyptians Eat the Same Food as Tuthankhamun? Review Of James Cuno’s Who Owns Antiquity?

https://www.modernghana.com/news/168893/1/do-present-day-egyptians-eat-the-same-food-as-tuth.html

Napoleon and the French used arguments similar to that of the British in stealing, Italian, Belgian, and German art treasures; they were saving those treasures and bringing them to Paris which was the new Rome where they would be better cared for in the Louvre.

17. Molemo Moiloa, Reclaiming Restitution:

Centering and Contextualizing the African narrative, Academic Fellows Report, Africa No Filter, July 2022 https://africanofilter.org/documents/Reclaiming-restitution-2022.pdf Introduction.

IMAGES.

Humboldt From with a Golden cross, Berlin, Germany with the inscription on the dome: ‘ There is no other salvation ,there is no other name given to men, but the name of Jesus, in honour of the Father, that in the name of Jesus all of them that are in heaven and on earth and under the earth shall bow down on their knees.’

Original text from Kaiser Friederich Wilhelm IV who combined two Biblical citations from Act 4.12 and Philippians 2.9.

Sylvie Njobati, Founder of REGARTLESS gets royal honour from the Fon of Fontem,Cameroon.

On the cruel exactions of the Germans against the Bangwa and the efforts of the Bangwa to recover their artefacts looted by the German colonial troops sent to punish them, see Chief Charles A. Taku, ‘The Legal and Moral Conscience of Justice in European Collections of Colonial Provenance:

The Bangwa Quest for Restitution and Reparations’’ in

, Provenance Research on Collections from Colonial Contexts, Edited by Claudia Andraschke, Lars Muller and Katja Lembke, 2023, art historicum.net.

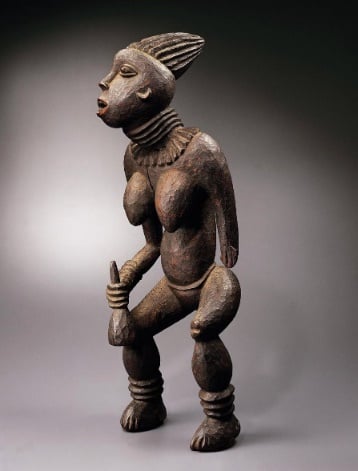

Bangwa Queen, Bangwa, Cameroon, looted by German colonial agent, Gustav Conrau now with Musée Dapper, Paris, France. The Bangwa Queen, once held by Helena Rubinstein and photographed by Man Ray, was bought in 1990 by Musée Dapper at a Sotheby auction for $3.4 million . The museum closed in 2017 for lack of public attendance and expensive costs arising from maintaining a first-class museum in an elegant expensive area in the heart of Pari,16 arrodissment, since 1986 Musée Dapper was certainly one of the best museums for African art.

Bettina von Lintig, The Bangwa Queen, A Journey into Art History. https://www.academia.edu/104275146/THE_BANGWA_QUEEN_A_Journey_into_Art_History

German slave castle, Grossfriederichsburg,1683, Princes town,Ghana.300,000 slaves were sent from this German fort. https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Princes_Town,_Ghana

Earlier attempts to deny German involvement in the Transatlantic Slave Trade have been largely abandoned.

German Involvement in the Transatlantic Slave Trade and Colonialism in Africa

Atlantic Slavery and Its Repercussions in German-Speaking Territories, c.1650 -1850 https://dkan.worck.digital-history.uni-bielefeld.de/?q=atlantic-slavery-and-its-repercussions-german-speaking-territories-c-1650%E2%80%931850

German Entanglements in Transatlantic Slavery

Edited By Heike Raphael-Hernandez, Routeledge,2019.

VIDEO: A German colony in Ghana? The Atlantic slave trade and the fortress of Grossfriedrichsburg. Roberto Zaugg Atlantic Slavery and Its Repercussions in German-Speaking Territories, c. 1650–1850 | DKAN | WORCK (uni-bielefeld.de)

Akufo-Addo’s recent attitude, utterances connote an arrogant nature, smack of an...

Akufo-Addo’s recent attitude, utterances connote an arrogant nature, smack of an...

NDC calls for immediate termination of contracts between SML and GRA

NDC calls for immediate termination of contracts between SML and GRA

NDC demands retrieval of monies paid to SML, calls for the prosecution of person...

NDC demands retrieval of monies paid to SML, calls for the prosecution of person...

NDC accuses President Akufo-Addo of attempting to cover up corruption and crimin...

NDC accuses President Akufo-Addo of attempting to cover up corruption and crimin...

Election 2024: ‘I don't want issues of independent candidature to plague NPP’ — ...

Election 2024: ‘I don't want issues of independent candidature to plague NPP’ — ...

2024 elections: Bawumia avoiding economic discourse because he has failed — Kwak...

2024 elections: Bawumia avoiding economic discourse because he has failed — Kwak...

Mustapha Ussif’s ‘Best African Sports Minister’ award signifies his exceptional ...

Mustapha Ussif’s ‘Best African Sports Minister’ award signifies his exceptional ...

Anti-LGBQI+ Bill: High Court’s verdict was predetermined – Sam George

Anti-LGBQI+ Bill: High Court’s verdict was predetermined – Sam George

Justification for continuation of SML-GRA contract ‘hogwash’ – Sammy Gyamfi

Justification for continuation of SML-GRA contract ‘hogwash’ – Sammy Gyamfi

Bawumia is a liar, google it and see – Osofo Kyiri Abosom

Bawumia is a liar, google it and see – Osofo Kyiri Abosom