'our research methods resemble the interrogations of an investigating magistrate much more than amicable conversations, and because, nine times out of ten, our methods of collecting objects involve forced purchases, if not requisition. All this casts a certain shadow over my life, and my conscience is only halfway clear. When all is said and done, as much as adventures like the taking of the kono finally leave me without remorse, because there is no other way to obtain such objects and because sacrilege itself is a rather grandiose notion, still all this constant buying leaves me perplexed, because I have a strong impression that we are going in vicious circle: we pillage the Negroes under the pretext of teaching people to understand and appreciate them-that is, ultimately in order to mold other ethnographers who will go in turn to "appreciate" and to pillage them.'

Michel Leiris. Phantom Africa, 2017. (1)

If the Sarr- Savoy report sought to free looted African artefacts from the long detention in French museums,(2) it can be said that the report entitled Shared Heritage: Universality, Restitutions, and Circulation of Works of Art, by Jean- Luc Martinez, the former director of the Louvre Museum, Paris, is clearly aimed at restraining African artefacts from leaving French museums or at any rate to ensure that a considerable number of them remain in France. (3) This recent report requested by President Emmanuel Macron on 27 October 2021 during the ceremony of restitution of twenty-six artworks to Benin, has suggestions that, if adopted by the French legislator, could also tend to bury the spirit of the Sarr-Savoy report.

The Martinez report was delivered on 25 April 2023 to the Minister of Culture, Rima Abdul Malak, and the Minister of Europe and Foreign Affairs Catherine Colonna. It is interesting to note that unlike in the case of the Sarr-Savoy report, there seems to have been no written request from President Macron to Martinez for a report but only verbal communication of the request. The report was received by the Ministers of Culture and Foreign Affairs as the President was in dispute with the Trade Unions and other groups on the reform of the pension system. His dealing with a cultural report would have been seen as either a diversionary tactic or lack of concern with the serious question of pensions.

The Martinez report proposes conditions for restitution that would prevent any quick return of looted African artefacts and seems to symbolize the awakening of groups against returning, believing the Sarr-Savoy went too far.

As we will see later, restricting restitution is done through several methods, some are evident in their intentions: others are more refined and demand some reflection.

Martinez submits twelve propositions

1. A new French law on restitution must recall the attachment of France to the principles of universality as understood in France and the inalienability of collections

2. Recall that restitution for diplomatic reasons is an ancient practice. Underline it is reasonable to frame this practice within a doctrine objective and favourable to writing a narrative between France and source countries in order to develop new partnerships. Future law or laws should enable the development of a new general legal framework to authorise the restitution of works to their countries of origin.

3. Elaborate a French restitution doctrine favouring a bilateral approach as distinguished from a normative, ahistorical, and multilateral system.

4. Criteria of 'restitutability' for cultural objects.

Three criteria of receivability

- The demand must come from the State of origin.

- Assure that no other State is demanding the same objects.

- Ensure that the request does not contradict previous bilateral agreements.

Two alternative criteria relating to the mode of acquisition:

- illegal character or

- illegitimate character

Four contextual criteria:

- A willingness for cooperation from the demanding State must accompany the restitution project.

- The requesting State must accept to conserve the patrimonial nature and presentation of cultural objects to the public.

- Requests must remain focused ('ciblées')

- The demands must remain strictly patrimonial and cannot include demands for financial reparations.

5. Additional precision concerning objects resulting from gifts or legacy.

The administration must first obtain the agreement of the donors or the successors.

6. Supplementary recommendations concerning objects resulting from war captures-prises de guerre.

7. Five criteria concerning human remains

- The demand must come from a State

- The remains must be du ly identified.

- The persons whose remains are sought must have died after the year 1500.

- Proof that the conditions of their exposition violate the principle of dignity of the human being.

- When returned, the remains must not be exposed.

8. Concerning the NAZI spoliations

- Extend to the years 1933-1945, the area of research of CIVS. (Commission d’Indemnisation des Victimes de Spoliation)

- Intensify research on acquisitions or gifts after 1945.

9. An original provision as a constructive response to demands concerning specific symbolic works that do not fulfill the criteria of 'restitutability': the notion of 'shared heritage .' It is a question of overcoming the question of legal property to envisage the question from the angle of accessibility of works by authorizing a form of depot, implying, in the long term, a common narrative of a shared history of objects.

10. Europeanise restitution by proposing specific tools for restitution demanded by Africans:

- A common declaration by African and European States on principles of restitution, on the model of the eleven principles of Washington' concerning the looted works in the context of antisemitic persecutions (1998).

- The creation of an Africa-Europe Fund public-private dedicated to African patrimony.

11. A historical and scientific analysis explains a transparent, collaborative, and scientific solid procedure limiting a maximum of 3 years delay between initial demand and the political decision on the substance.(not a national commission but bilateral experts) case by case.

12. After adopting the proposed laws, parliament shall be regularly informed of the demands for restitution and the government's decisions.

The government could also transmit to parliament a report on restitutions every year. For complex cases, the government could send to parliament the inter-governmental agreements formalizing the cultural cooperation projects accompanying the restitutions, including the creation or renovation of museums intended to house the restituted works.

We want to comment on some of the proposals by Martinez.

Universalism

Recalling the notion of universalism is to ignore criticisms that have been made against this notion and the fact that a form of universalism, connected with the European Enlightenment was at the base of colonialism in Africa and Latin America; the concept implied a debasement of all peoples and cultures outside Europe. Does France need to invoke this concept when dealing with restitution which inevitably recalls the colonial period with all its horrors and injustices? It can also be a manifestation of colonialism to insist on a concept that has caused so much harm in the world.

Conditions for restitutability

The first condition of receivability posed by Martinez is that the demand for restitution should come from a State. This is aimed at excluding cultural and ethnic groups that do not constitute a State. These groups, often called communities, are thus excluded. Ironically, most African cultural objects were looted from ethnic groups that do not now have a State but at the time of the colonial encounter, were either States or on the way to becoming one. African peoples resisted colonial aggression under the leadership of their kings and chiefs. Such restrictions constitute a denial of the rights of Indigenous people as provided in the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (2007).

Article 11, para 1 provides:

1. Indigenous peoples have the right to practise and revitalize their cultural traditions and customs. This includes the right to maintain, protect and develop the past, present and future manifestations of their cultures, such as archaeological and historical sites, artefacts, designs, ceremonies, technologies, and visual and performing arts and literature.

Shared Heritage.

Martinez reintroduces the concept of shared heritage which we thought had been abandoned. This concept is as an answer to restitution demands concerning objects that do not fulfill the conditions of 'restitutability' and attempts to go beyond the legal concept of property by adopting a form of the deposit that tends towards a common narrative on a shared history of the objects.

Martinez notes that there is no unanimous view in the African countries concerning restitution. According to him, some countries such as Benin or Côte d'Ivoire seek to reconstruct a future and common imagination based on a logic of partnership. Other African voices- especially those of the diaspora- do not share this view and consider that restitution must be unconditional. They say it is not for the thief or his 'accomplice' to fix the conditions for the return of stolen objects.

Martinez wants to lay the basis for new forms of partnership, to circulation of works and not view the question exclusively from the angle of the legal property but rather on the accessibility of French collections in Africa and elsewhere. Martinez calls in aid of this 'shared heritage' scholars such as Souleymane Bachir Diagne for his expression 'objets-rhizome,' objects that are said to be 'métisses.' According to Martinez, the idea is to construct a common world through this 'patrimoine partagé.'

We learn from Martinez that many African artefacts in France entered France 'legally,' and 'legitimately.' This view will surprise many. According to Martinez, he dug up this notion of 'shared heritage' at the demand of Ivoirian and Benin partners.

After several consultations, it appeared to Martinez desirable' to go beyond the question of legal property in order to envisage the question from the angle of accessibility.'

This gigantic revolution will enable one to view many questions concerning restitution from the perspective of accessibility, especially if we consider possibilities under modern digital systems.

Martinez does not envisage the establishment of a list of works that fall into this category of symbolic works. (4) Whether an African work falls into the category of shared heritage will, therefore, be decided on case by case. The issue must be solved by an agreement between the two States to send the object out as a deposit in France or Benin. If the former director of the Louvre and his formidable team of consultants and advisers cannot tell in advance which African work of art falls into the category they have created, who else can?

With all due respect to Martinez, this talk of shared heritage is just a means to keep the African artefacts that the French like and do not want to part with.

Gou, Fon god of war and metal, now a French-Fon god of war?

Fascination as justification for retention.

Readers will recall that when France restituted twenty-six artefacts to Benin in 2022, the famous statue of the Fon god of war, Gou was not on the list. President Talon, Benin, drew attention to this absence and his dissatisfaction in his speech at the signing ceremony of agreements between France and Benin. President Talon said he could not be expected to be satisfied with the twenty-six artefacts he received, especially since the god Gou was not among them. He envisioned a second wave of transfers to follow. When President Macron visited Benin in July 2022, the authorities there informed him that they were still waiting for Gou.

I looked at the web pages of the Louvre and could not find Gou. Suspicious of Western States in matters of African artefacts, I wrote:

'But the quest for the return of Gou will be a long-drawn-out battle since the French think that African treasures that look extremely modernistic such as the sculpture of Gou are more French than African and should stay in Paris* under one pretext or other. They consciously or unconsciously reverse the historic imitation of African art by modern French artists such as Picasso. Pablo Picasso and Guillaume Apollinaire admired the Gou statue.' (5)

I was not surprised that the statue of Gou was named as a possible object for this flexible classification (6) This classification as shared heritage may help to bring Gou to Benin, but it can also ensure that he will return to France. We will have to look at the precise wording of the agreement between France and Benin on this statue. Such a classification would also imply that the figure does not belong to Benin alone!

The classification in this category could also be helpful when provenance research does not give any clear indications to decide on the legality or legitimacy of a reclaimed object.

But was there ever any serious doubt that this impressive work of art belonged to the Dahomean King Béhanzin and was looted by the French General Dodds and his troops after the defeat of the African King in 1892?

Common Declaration of African and European States on principles of restitution.

One suggestion by Martinez is to have African and European countries adopt a joint declaration on restitution principles on the model of the Washington Principles on Nazi-Confiscated Art (1990) to avoid the diversity of European approaches to African restitution. Hermann Parzinger from the Prussian Foundation for Cultural Heritage(PSK) also suggested in 2018 that we needed a set of rules on the Washington model. We argued we would be better off to abide by the United Nations resolutions on the return of cultural property to their country of origin. The delays in getting States to agree on general principles of restitution at a time when Europeans did not even want to hear the word restitution. Western States have reluctantly and slowly restituted a few African artefacts. Museums such as the British Museum are not inclined to follow other museums on the restitution path. African States do not have a common policy. Any attempt to secure an agreement between Western and African States on general principles can only be to the advantage of opponents of restitution; there will be a long delay. Besides, we need evidence that the Washington principles are working as well as one might wish.

An administrative, transparent, and collaborative procedure for restitution.

Martinez proposes an administrative procedure that may seem reasonable but complicates it with other conditions. He suggests that even before restitutions start, the Ministries of Culture, Armies, Higher Education, and other cultural institutions encourage their institutions to do provenance research and put online the basic facts concerning artworks and their archives.

States requesting restitution should receive a first answer within two months based on the receivability criteria. Requests should be sent to the Minister of Culture. If the first response is negative because it is too general, the demanding State might be sent a proposal for collaboration in order to define better the request made.

If it is decided to receive the request, relevant provenance ce research will be done with scholars from the country of origin of the object in question.

Martinez proposes a bilateral commission decided by France and the country concerned together and which will have within it a scientific committee whose duty it will be to draft a report base on scientific expertise establishing the provenance of the objects, conditions of acquisition, its history and applicable legislation at its time of acquisition at the end of which it advises on the restitution.

Martinez prefers such an ad hoc commission to the alternative of a permanent scientific commission. Martinez explains his preference for an ad hoc commission thus: a permanent commission presupposes that representative scientific scholars are omniscient, but we know there is no universal knowledge, and such a commission may never acquire scientific credibility.

The report of the scientific committee will be solemnly to the two governments and should be published.

The opinion of the scientific committee will not be binding on the political decision-makers.

The costs involved in restitution requests - missions of members of the scientific committee, transport of the works, eventual restoration of the pieces -shall be at the expense of the demander of the request!

The nature and intentions of the Martinez report come out here. The French who took these works from the colonies, often with violence, and kept them for hundred years, earning income from exhibitions and loans of the artworks and not paying any compensation to the African States, are again to benefit from new payments from the African victims.

The final decision on restitution will by a decree of the French Senate, which will again examine whether the decision conforms to the criteria of 'restitutability.' The decision could also take the form of an intergovernmental agreement which in French law is superior to ' loi ‘and can constitute an exception to the principle of inalienability.

Martinez proposes that the demand for restitution and the final decision should not take more than three years.

We have difficulties with some of Martinez's proposals, but we hope the French legislator will not accept them. We mention here a few of these objections.

The proposition that all demands must come from State and not individuals or communities deprives individuals and Indigenous peoples of their rights as provided by the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. Most demands will come through the State but suppose the State, for political or racial grounds, does not support the request, should 'le pays de liberté at least not have a look at the demand?

To insist that when States seek restitution, they must demonstrate a will and readiness for partnership projects seems wrong. It is a neo-colonial device for continuing to control and supervise African countries in the use of their artefacts and resources. Restitution should be unconditional, without limitations binding the demander with cooperation agreements that limit their rights or control their use.

Similarly, to insist that the demanding State should undertake to preserve the heritage character of objects and their public presentation is neo-colonialist. Martinez goes as far as to suggest that illicit traffic may be a relevant factor in this classification. He even suggests that President Talon of Benin classified the 26 artefacts returned Benin as national treasures and not royal treasures as a safety measure.(7) President Talon, like many other African Presidents, may have other reasons, more important than traffic in cultural good, for wishing to convert, as quickly as possible, looted royal artefacts from France into Benin national treasures. For multi-ethnic or multinational countries in Africa, the stability of the State and national cohesion are overriding factors.

To require in advance that an African State requesting restitution of a cultural object must promise to maintain its heritage nature and display it in public indicates that the French still need to give up their ideas of assimilation. We Africans are not Europeans and may not have a museum for displaying an object, but we want it back. The item may be sacred or religious and not intended in our traditions for public display. Will the French try to keep this back even though it is looted or stolen if we cannot make the promise they are requesting?

Another reason for insisting on the patrimonial nature of the demand and rejecting any financial compensation is to prevent communities from demanding reparation, as appears to have been the case of the Bijans, who sought monetary compensation of 150 million euros for the detention of the Djidji ayôkwé talking drum the French took in 1916. Thus, the French are determined not to pay anything for the considerable damage and deprivation they caused. But is this French position compatible with any sense of justice and fairness?

The idea to obtain the consent of donors of gifts of objects to museums before proceeding with restitution seems strange. Certainly, donors or their successors should be informed of any demand for restitution concerning their donation but is their consent necessary if it is established beyond doubt that the object was stolen or looted?

When President Macron requested a former director of a museum with many looted artefacts to reflect on the questions of restitution, none of us expected sweeping proposals facilitating returns. Museum officials are trained to preserve the objects in their museums and are certainly the wrong persons to entrust with such a task. The French government and parliamentarians will no doubt discuss the Martinez report and determine what recommendations to retain. Whatever they may think of restitution, they are aware of the fundamental changes since the Sarr-Savoy report of 2018 that followed the historic speech of President Macron in 2017 at Ouagadougou. They know the enthusiasm caused by the French restitution of twenty-six artefacts to Benin in 2022. They will have noticed the restitution of Benin bronzes from Britain to Nigeria, and despite the British Museum, the transfer of legal rights in 1130 Benin bronzes to Nigeria by Germany. The promises of restitution by Belgium, and the Netherlands, are factors they will also consider besides the Martinez report.

Macron and his government must fulfill the hopes and promises raised by his famous Ouagadougou declaration and reinforced by the Sarr-Savoy report if we are ever to have genuine cordial relationships between Africa and Europe. The subtitle of the report by Felwine Sarr and Bénédicte Savoy, The Restitution of African Cultural Heritage. Toward a New Relational Ethics, 2018, was a summation of what our time requires.

It is no use trying to create an impression of common heritage if European States are unwilling to resolve restitution issues by returning items they stole or looted from Africa. We must accept that Africa and Europe have no shared history in any positive sense. You cannot consider slavery and colonialism as common history unless the slave and his master, the murderer, and his victim, can be said to have a common history in the sense of having been involved in the same action. The idea of common history only comes up in restitution when Africans demand the return of their artefacts. I have never heard anybody suggest that the Nazis and their victims whom they robbed and killed have a common history.

Pope Francis has recently expressed support for restitution:

But let us go back to restitution. To the extent that one can make restitution, which is a necessary gesture, it is better to do it. There are times when one cannot, there is no political possibility or a real, concrete possibility… But to the extent that one can make restitution, let it be done, please, this is good for all. So as not to get used to putting one's hands in other people's pockets! (8)

Will the French listen to the head of the Catholic Church?

Let us face history, however ugly it may be, with realism and demonstrate our determination to develop better relations through concrete actions. Rhetoric alone will not help us.

"In my experience,most museum people are very well-meaning and are the first to acknowledge problems in the sector. But it's rhetorical. Few people are ready to grapple with their own inadvertent complicity in a system that benefits them, or that rewards them for a professionalism that is actually quite harmful. It is hard to admit that many of the practices you have been trained in are violent in how they make different forms of knowledge and people invisible or invaluable.

So, there is resistance which manifests itself in all kinds of ways. But no one will come out and admit they actually don't support the change because they are more afraid of being called' racist' or' colonial' than looking inward at what may be subconsciously doing that upholds a racist colonial system". Ngaire Blankenberg. (9)

NOTES

1. Leiris letter to Zette, September 19,1931 cited at p.163 in Phantom Africa by Michel Leiris, translated by Brent Hayes Edwards, Seagull Books, 2017, ISBN: 978 0 8574 2 3771. With this recent English translation of Afrique Fantôme by Michel Leiris, first published by Gallimard, Paris in 1934, English readers have now the possibility to appreciate the significance of this historic book by Leiris. Anyone interested in the restitution of African artefacts or colonialism will do well to read this major work which is available also in German, Portuguese, Spanish and Italian: The German translation of the French original, Afrique fantôme is entitled, Michel Leiris, Phantom Afrika - Tagebuch einer Expedition von Dakar nach Djibouti 1931-1933, Band 1 und Band II, 1980, Syndikat Autoren-und Verlagsgesellschaft, Frankfurt am Main. The Portuguese version is entitled A África Fantasma, 2007, published by Cosac Naify, Sao Paulo, Brasil. The Spanish edition is entitled: El África fantasmal, by Tomás Fernández AZ and Beatriz Eibar Barrens, 2007, Ed. Pre-Text’s. The Italian edition is entitled, L’ Africa fantasma by Aldo Pasquali, Rizzoli Editore,1984.

2. Felwine Sarr and Bénédicte Savoy, The Restitution of African Cultural Heritage. Toward a New Relational Ethics

https://drive.google.com/file/d/1jetudXp3vued-yA8gvRwGjH6QLOfss4-/view

3. Jean-Luc Martinez, Patrimoine partagé : universalité, restitutions et circulation des œuvres d’art, Remise du rapport Patrimoine partagé : universalité, restitutions et circulation des œuvres d’art de Jean-Luc Martinez (calameo.com)

4. Martinez states :

‘Pour certains de ces cas, les neuf critères de restituabilité proposés dans le présent rapport n’auraient pas été opérants car ces œuvres étaient entrées légalement et légitimement dans les collections publiques françaises. Il s’agissait pourtant à chaque fois d’objets à valeur symbolique, dans un contexte diplomatique spécifique’.

A la demande de nos partenaires ivoiriens et béninois notamment, nous avons dans un premier temps creusé l’idée d’une propriété partagée. Mais ce concept – que nous avions déjà envisagé, au Louvre, à l’occasion de l’acquisition en 2016 de deux tableaux de Rembrandt, les portraits des époux Soolmans, qui intéressaient la France et les Pays-Bas – est incompatible avec le droit patrimonial français.

Après de nombreuses consultations et au terme de notre réflexion, il nous semble souhaitable de dépasser cette question de la propriété juridique pour envisager la question sous l’angle de l’accessibilité.’pp.69-71

‘Nous ne préconisons pas la création d’un inventaire à partir des œuvres des collections nationales : un tel travail prendrait des années voire des décennies et serait très difficile à réaliser dans la mesure où cette notion de valeur symbolique reste subjective : le caractère symbolique d’une œuvre ne peut être appréciée que du point de vue des autorités du pays d’origine et pourrait évoluer dans le temps. Nous proposons donc une approche au cas par cas.’

5. K. Opoku, How far have we gone in the struggle for the Restitution of African artefacts?

https://www.modernghana.com/news/1179136/how-far-have-we-gone-in-the-struggle-for-the-resti.html

6. ‘L’une des premières œuvres qui pourrait entrer dans cette catégorie d’un « patrimoine partagé » pourrait être la statue du dieu Gou : l’historique de cette œuvre tend en effet à montrer qu’elle ne remplirait pas les critères justifiant une restitution (ce n’est pas une saisie car l’œuvre aurait été abandonnée volontairement). Pour autant c’est une œuvre à la fois importante pour l’histoire du Bénin mais qui, depuis plus d’un siècle qu’elle est en France, a inspire des artistes et a été exposée dans des expositions internationales. Elle est donc devenue une œuvre riche de cette histoire plurielle. Son exposition au Bénin par le truchement de ce dispositif « patrimoine partagé » permettrait certainement de répondre aux attentes béninoises et d’apporter une nouvelle contribution à la coopération culturelle avec ce pays africain.’

7. C’est pour cette raison que, lors des restitutions au Bénin, le Président Talon a tenu à présenter les 26 œuvres de retour comme des biens nationaux et non royaux : « les objets sont partis comme bien royaux et reviennent comme trésors nationaux ». Cette obligation du maintien du caractère patrimonial du bien nous paraît pertinente même si elle est parfois contestée. Martinez, p.57.

8.https://www.vatican.va/content/francesco/en/speeches/2023/april/documents/20230430-ungheria-voloritorno.pdfhttps://apnews.com/article/vatican-restitution-indigenous-parthenon-0e486d653bcac89f94854430ce29faf0.

9.Ngaire Blankenberg, on her resignation from the Smithsonian Institution where she was the director of the Museum of African Art. She had been largely responsible for the initiative in establishing the Smithsonian’s policy of ethical returns, inter alia, that made her unpopular with certain quarters in the museum world. https://www.theartnewspaper.com/2023/05/09/smithsonian-national-museum-african-art-ngaire-blankenberg-resigned

IMAGES

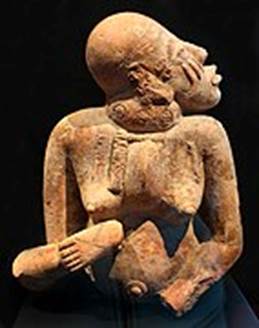

Djenne female figure, Mali, now in Musée du quai Branly-Jacques Chirac, Paris, France.

Kwayep, mother and child, Bamileke, Cameroon, now in Musée du Quai Branly-Jacques Chirac, Paris, France.

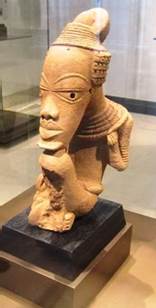

Produced in 1858, by Akati Ekplekendo, Benin, now in Musée du Quaui Branly-Jacques Chirac at the Pavillon des Sessions ,Paris, France. Among the impressive African objects in the Pavillon is the sculpture of Gou, God of iron and of war that the French looted in 1892 from the former French colony ,Dahomey, now in the Republic of Benin. Benin has requested the restitution of Gou who was not among the twenty-six artefacts France returned in November 2021.

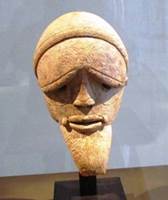

Nimba shoulder mask, Guinea, now in Musée du Quai Branly-Jacques Chirac, Paris, France.

Gold jewel of two crocodiles, Baule, Côte d’Ivoire, now in Musée du Quai Branly-Jacques Chirac, Paris, France.

Djidji Ayokwe,’ tambour parlant’ ,Côte d’Ivoire taken by the French in 1916, now in Musée du Quai Branly Jacques Chirac, Paris ,France. The drum should return by early next year to Abidjan.

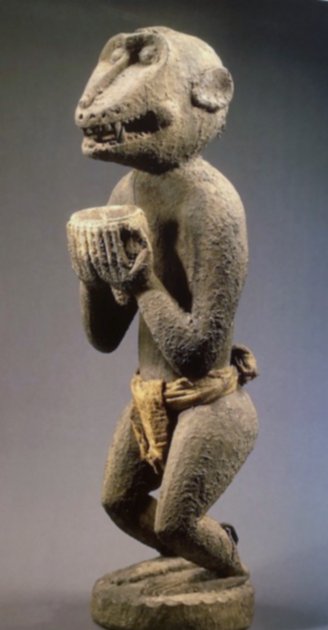

Cynocephalus carrying a bowl, Baule, Côte d’Ivoire, now in Palais des Sessions, Musée du Quai Branly-Jacques Chirac, Paris, France.

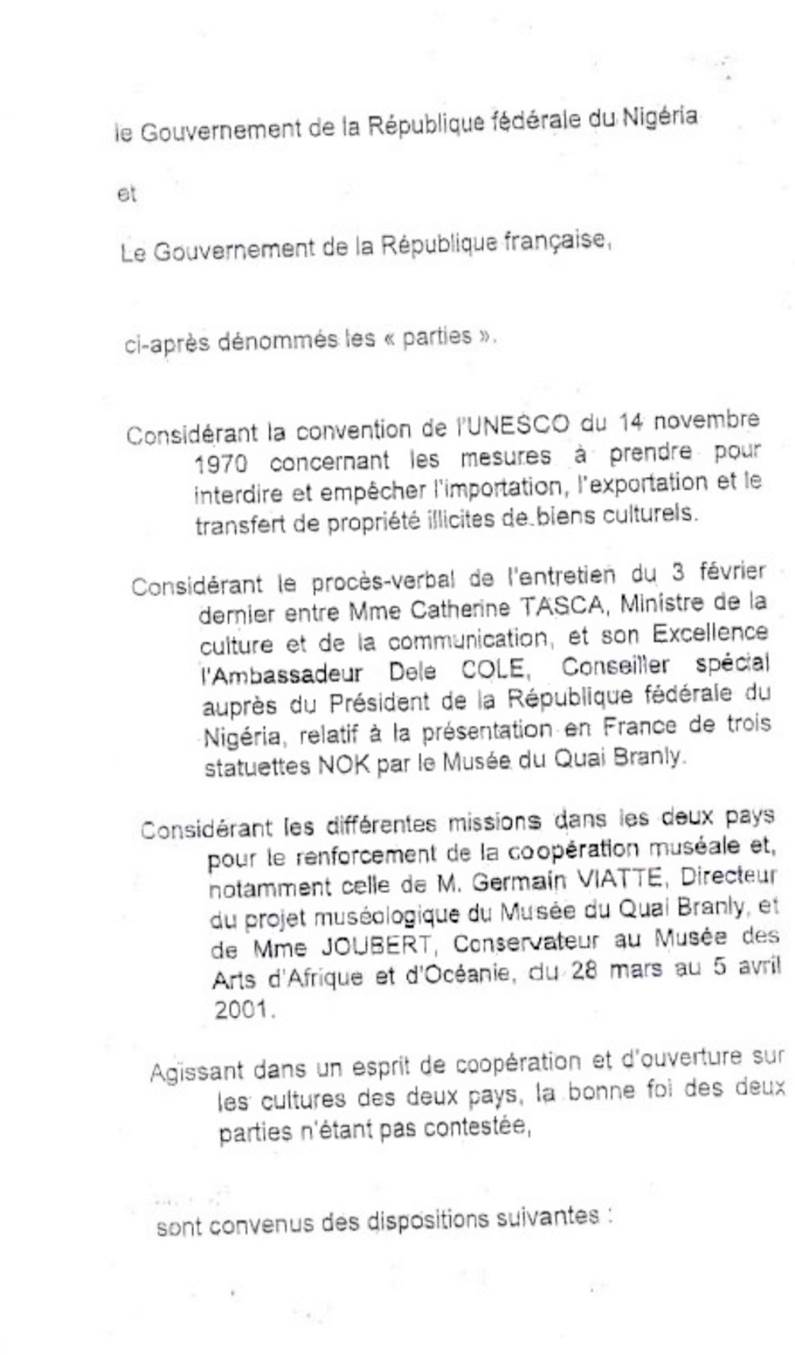

ANNEXE I

AGREEMENT BETWEEN NIGERIA AND FRANCE

(February 2002)

We publish below the text of an agreement between Nigeria and France in 2002 that was widely criticized and condemned although the agreement itself was not revealed to the general public.

The agreement concerned three Nok sculptures which the French had bought in an auction in Belgium, knowing fully well that the items were illegally smuggled out of Nigeria. The ICOM Red Book on Africa had forbidden the export of such objects that were fundamental to the history of Nigeria and Africa. After serious condemnations from writers and ICOM, France and Nigeria entered into a post-factum agreement that would legalize the illegal purchase. Lord Renfrew described the act, and the role of the French President Jacques Chirac as follows:

‘His attitude is dishonourable. I regret that Nigeria was weak enough to accept to sign an agreement in order to give an appearance of legality to this acquisition. But above all, the fault lies with the French president who made the request. The responsible officials of the museum should be ashamed to have placed their Head of State and their own country in such a deplorable situation’’.

Lord Renfrew, in interview with Noce Vincent in Liberation, entitled,’’ L’attitude de Chirac est déshonorante,’’ http://www.liberation.fr See also

Paris conforte l’archéologie, http://ww.libération.fr ‘Des pillages alignes sur le marché’

The agreement with French shocked many who were concerned with the preservation of Nigerian culture. The leading Nigerian authority on cultural law, the late Prof. Folarin Shyllon described the agreement as an ‘unrighteous conclusion,’ F. Shyllon, Negotiations for the Return of Nok Sculptures from Nigeria-An unrighteous Conclusion, http://portal.unesco.org

Shyllon, Folarin. « Negotiations fo the Return of Nok Sculptures from France to Nigeria – An unrighteous Conclusion ». Art, Antiquity, and law 8 (2003): 133-148.

See also, Kwame Opoku, Revisiting Looted Nigerian Nok Terracotta Sculptures in Louvre/Musée du Quai Branly. Arthemis,

Affaire Trois sculptures Nok et Sokoto – Nigéria et France

It is encouraging to see that Martinez cites the illegal purchase of Nok treasures and their later irradiation from the list of inventories of the Musée du Quai Branly-Jacques Chirac as a ground why France should now adopt a proper legal doctrine to avoid such contortions. He does not however mention that the three Nok sculptures are still in the Palais des Sessions as on depot based on the agreement cited below. The agreement is for 25 years, renewable. The depot concept could be used to keep many African artefacts, deemed as shared heritage, in France.

The three Nok sculptures illegally bought by the French, now in possession of Musée du Quai Branly -Jacques Chirac, the Palais des Sessions, Louvre, Paris, France. These sculptures are held in Paris with a post factum consent of the Nigerian authorities even though the ICOM Red Book for Africa forbids their export outside Nigeria.

Seated male figure.

Terracotta piece with figures in low-relief.

Figure of a bearded male.

Lay KPMG audit report on SML-GRA contract before Parliament – Isaac Adongo tells...

Lay KPMG audit report on SML-GRA contract before Parliament – Isaac Adongo tells...

Supervisor remanded for stabbing businessman with broken bottle and screwdriver

Supervisor remanded for stabbing businessman with broken bottle and screwdriver

NDC watching EC and NPP closely on Returning Officer recruitment — Omane Boamah

NDC watching EC and NPP closely on Returning Officer recruitment — Omane Boamah

Your decision to contest for president again is pathetic – Annoh-Dompreh blasts ...

Your decision to contest for president again is pathetic – Annoh-Dompreh blasts ...

Election 2024: Security agencies ready to keep peace and secure the country — IG...

Election 2024: Security agencies ready to keep peace and secure the country — IG...

People no longer place value in public basic schools; new uniforms, painting wil...

People no longer place value in public basic schools; new uniforms, painting wil...

'Comedian' Paul Adom Otchere needs help – Sulemana Braimah

'Comedian' Paul Adom Otchere needs help – Sulemana Braimah

Ejisu by-election: Only 33% of voters can be swayed by inducement — Global InfoA...

Ejisu by-election: Only 33% of voters can be swayed by inducement — Global InfoA...

Minority will expose the beneficial owners of SML, recover funds paid to company...

Minority will expose the beneficial owners of SML, recover funds paid to company...

Prof. Opoku-Agyemang has ‘decapitated’ the NPP’s strategies; don’t take them ser...

Prof. Opoku-Agyemang has ‘decapitated’ the NPP’s strategies; don’t take them ser...