On the lack of Mirrors in Ghana

Some of these nations’ development journeys, when in hindsight looked back on, seem almost flawless. As though a hand, unknown, put together series of events, each meaning something, each interconnected, enabling the expansion of the West. Sometimes the hand looked as though that of the devil him/herself, but other times as though none other’s, but the Creator Him/Herself. Because when the Industrial Revolution happened, as gradual yet steady as it was, a spillover effect was seen in every aspect of the West’s individual national lives—particularly that of America’s.

It is almost silly being this philosophical when the matter at hands is movies. But as we saw last week, this industry as seemingly flimsy as its end may seem—entertainment—the birth of the industry itself was by a painstaking process of industry, of ingenuity, science, and technology. And as it always is the case in any national life, the economic aspect goes on to inform sociological dynamics. A country like America is what it is now, it thinks how it does now, because of its own peculiar set of events experienced. America’s journey—among others, its industrial journey, its economic journey—those go on to form the very crust of the American ideology.

I am going to go ahead and note right here in this third paragraph of today’s piece. Let’s not drag matters, the ultimate aim of this new series of article— starting from last week’s ‘America’s Hay Days’—is to delve into Africa’s pretentiousness, one borne out of a very much expected Stockholm Syndrome suffered owing to our past, one that with conscious efforts, we can work to uproot, but one that we seem to be comfortable festering in.

I really got myself giggling last week when I wrote, “...Persistence of vision is that which keeps the viewer from seeing those blank or black spaces, or breaks existing between those successive images made to move past in awfully quick paces. Whether it is the human brain that tricks the eye into believing; or the eye, the brain; or as some conclude, both, this phenomenon is, at the end of the day, made possible—courtesy our sensory organs.” I thought I was being slick with that because you see, underneath that harmless description of the ‘persistence of vision’ phenomenon, what I was actually honing was a metaphor.

In this fast-paced world, driven—and let’s be frank here—not by us, but by the developed world, with things moving with the speed of light, it is very easy for a developing nation like ours, Ghana, to be tricked into not seeing the blank or black spaces in between certain successive Western events—the ‘blank or black spaces’ being our Black reality. A friend of mine keeps saying something: “Whenever I see a very beautiful lady, in my mind I feel like I look exactly like her, and then I look in the mirror, and that delusion is quickly erased.” That is one powerful act of self-deprecation and brutal honesty. Don’t worry about her, she’s way too brilliant to be genuinely bothered by this. But this delusions our minds and eyes, or both are capable of causing on us, they are very powerful. So, it is very understandable that a developing country like Ghana, having looked at this lady called America for so long, having been flooded with her way of living for so long, it is mighty understandable that this lady, Ghana, would begin to think herself, America. It doesn’t help matters the history we have had with the West, where we were literally forced into replication. “Look at me! Learn from me!” has been the theme song of our peculiar history with the West. Powerful, this claws of delusion. But all it takes is for one to look in the mirror...

Now tell me if the term ‘persistence of vision’ doesn’t make you giggle.

America doing it’s thang!

We promised ourselves last week, movies this week. So, let’s get right to it. And let’s start from the 1920s. Because having developed sound-on-film, cinema as we know it now had taken real form. And as we discussed last week, storytelling in film was now a realised artform. But what is it they say…? Oh! sex sells. They keep saying this and keep forgetting about violence. Violence sells just as equally, experience has shown. I cannot tell precisely why this is so. Maybe it’s sadism, the urge to see another commit in pretense, an act one cannot, on their own accord, commit upon another; or maybe it’s Schadenfreude, the happiness one feels from witnessing the downfall, shame, or failures of another; or maybe it’s the feeling of catharsis we are after. For it wasn’t long before Hollywood, the new age storytellers, were flooding the public space with movies sex-and-violence dense. Let’s not hide behind the otherwise distinguished notion of ‘art’ to hide the fact that what drove this trend was pure capitalism—money.

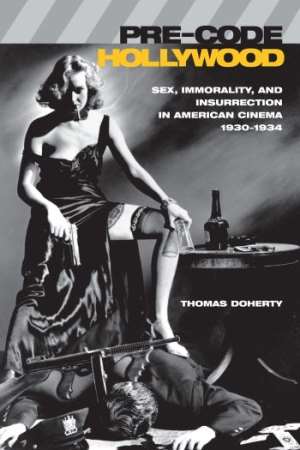

The Pre-code Era

In the hay days of cinema, before the institution of the Hays Code and all subsequent code systems to regulate the movie industry, contents released for general viewing were rife with sex, sex, and sex—infidelity, promiscuity, prostitution—illegal drug use, profanity, violence, miscegenation, etc. Yes, you heard me right. I could shout it out if it helps: pre-late-20-century America when listing immoral acts had right there, atop those lists and amidst acts like violence, illegal drug use, prostitution, etc., romantic relationships between Blacks and Whites. Marriage between Black and White people was deemed offensive to the fabric of public morality. It was a crime in fact. But more on that later.

But with these pre-code era movies, these ‘immoral acts’ although shown on film, were not so done, so as to demonise them. Yes, I put immoral acts in sarcastic quotation marks, because of ‘miscegenation.’ Storylines sometimes in the end had bad guys donning the cloak of protagonist—crime was glorified to no end. Not only was Hollywood seeming to be implying that ‘sex / crime sells in cinema’, but also that ‘sex / crime sells in actual life’.

Take the movie, ‘Scarface’, a 1932 gangster flick loosely based on the life of Al Capone, a.k.a. Scarface, an American gangster who ruled Chicago in early 1920s at the age of 26 years; a bootlegger of America’s infamous Prohibition Era, one who would blow up establishments with bombs, killing about hundred people as a result, when they failed to patronise his illegal activity—his booze business.

‘Scarface’, the movie, chronicles the life of its protagonist Tony, as he navigates the gang scene of Chicago, ruthlessly rising from rock bottom to becoming leader of a crime syndicate. Like all American portrayal of Italian gangster lifestyle, it had its fair share of ‘Tonys’ and ‘Johnnys’ warring it out, balancing strict adherence to brotherhood of the gangster-code, with a trademark unapologetic war-like gruesomeness. Throughout the movie, the audience cannot help but find itself rooting for Tony, owing, I guess, to some sort of ‘the better of two evils’ effect, where one in the confines of cinema, cannot escape evil—hence has to make a choice between two evils, Tony or Jonny. At the end of the movie, Tony, the twisted protagonist (if you will) dies, but this does not erase the romanticisation of crime that ensues throughout the movie and a lot like its kind.

The Code Era

The Code Era of Hollywood was bound to happen. Because, among a couple of other factors, these actors and actresses perhaps having played pretend for so long, found themselves, victims of the fantasies they themselves played. It wasn’t long before scandals after scandals was hitting the industry. Its players were replicating their characters in real life, it seemed. Notable among these scandals was the gory murder of actor/director William Desmond Taylor, the notorious drug use of Wallace Reid, and the false accusation and trial of Fatty Arbuckle (the mentor of none other but Charlie Chaplin himself) for rape and murder.

Fatty was acquitted, for there were truly no real grounds for this accusation, but Hollywood had its taint spread all across its players. The public didn’t seem to care whether or not the man was actually guilty; so far as he was employed by the leviathan of an organisation, Hollywood, he was inherently guilty of all things atrocious. It goes without saying that this wave of scandal-fueled film industry was fueled by yet another communication medium—the media. America’s media’s dedication to printing the ‘truth’—by that we mean unnecessary sensationalism, glorified gossips—was unparalleled. Again, let us not hide behind ‘art’ when that which drove these incessant flooding of the public with these gratuitous stories was once again the monarch-supreme—money.

Hollywood was a money-making industry, but it was at this point in crises mode. The American public, still then, pretty much in tune with the notion of right and wrong were rallying against this industry—although many times that which comprised ‘right’ and ‘wrong’ were woefully misguided and were themselves immoral. Hollywood had morphed into some sort of glorified brothel and gangland—it had to be done away with. States responded to public demands by enacting censorship codes, beginning as early as 1897 (with the passing of Maine’s censorship law against exhibiting boxing films), to the censorship law of Chicago in 1907, and that of New York in 1908. By early 1920s, a total of thirty-seven states had issued in total close to one hundred film censorship codes.

This was bad for businesses. What ensued, as noted last week, in an otherwise national phenomena such as movies, was inconsistent censorship laws from one state to the next regulating the same piece of art. That meant if thirty-seven states censored one movie according to their differing codes, thirty-seven versions of the same movie had to be made. This was insane. One obvious solution to this pocket-size legislative irregularities seemed to be federal regulations. So then inconsistent state legislations, coupled with the threat of federal government’s involvement in the censorship legislation game, meant Hollywood had to act quickly. Thus came the self-censorship era.

To be Continued…

Let’s pull a ‘to be continued’ as movies do and end this week’s piece right here. We will pick up from here next week, delving further into the sociological, economic, and socioeconomic backdrop that inspired one aspect of America’s national cake—its artform, cinema. But we will cap off properly with ‘Scarface.’

[Let me quickly add that we will begin a new series on Ghana’s energy sector—a series resulting from a series of discussions had with the nation’s top brains on the matter. Coming soon on a B&FT near you, each and every Thursday…]

Title reads: ‘Scarface’

In the 1920s, Tony, a young Italian man arrives in America’s Chicago. Naturally, he finds himself in bad company, particularly in the arms of Johnny, an Italian mafioso. Johnny orders Tony to kill a certain ‘Big’, the head of a crime ring in South Side. Tony wins big putting down Big. And after killing Big who’s the captain now? Johnny. Gaining control of the deceased Big’s crime organisation, Johnny naturally makes Tony his right-hand man.

They engage in bootlegging activities, resorting to intimidations, murders, etc. to undercut competitors. But not all competitors are cut from the same cloth, so Johnny warns Tony never to mess with the Irish gang that ruled the North Side and was led by the ruthless O’Hara. Tony responds, “yoo mate”, but in fact, he didn’t “te”, as he went on and did the exact opposite. Driven by youthful exuberance and anarchy, Tony was raiding bars owned by O’Hara, calling to himself the attention of the police and competitor gangs alike. Of course, O’Hara was not happy with this. And fearing O’Hara, Johnny was himself not happy with this. This Tony mentee of his had grown cancerous; he had to cut him off. By that I mean whack him; by that I mean kill him—it’s the gangster thing to do. Tony responds to this by further stoking the flames—going after Johnny’s girlfriend, Poppy (I’m not making these names up). Once again, it is the gangster thing to do.

Now, we have here Tony who has Johnny and O’Hara chasing him, even while he’s chasing Poppy. Does he run? No, that’s not gangster. What a real Mafia would do is to go after those who come after him. Which is exactly what he did, first to O’Hara. Tony didn’t waste time sending one of his flunkies to kill O’Hara. Successful, he spreads his dominion over the North Side. But a dead leader didn’t mean the original North Side crime organisation was disbanded. Seeking to avenge their dead boss, the North Side gang members wage war against Tony and his gang. Tony wins once again as one after the other, went these gang members to their early yet impending graves.

But why go through all these killings if not so you could dance with your boss’s girlfriend right in front of him? This is exactly what Tony does with Poppy to Johnny. It was settled: Johnny must kill Tony. But what in fact happened was: Tony killed Johnny, making Tony the one and only leader of the North Side gang. He had killed all his enemies, he was king of his criminal organisation, and most importantly he ended up with the girl.

But who is Tony if he doesn’t proceed to live the dramatic? He kills his sister’s lover, because he loved his sister too much to bear the thought of this. His sister is angry at him because of this and avows to kill him in revenge. But she comes to find her brother being raided by the police. To kill or not to kill was her dilemma, but she chose to join forces with her brother instead against the police. She’s shot down and dies. He’s next to go—into a gutter he went. Onlookers cheer at their downfall, as an electric billboard a recurring theme in the movie, flickered the words ‘the world is yours’.

Fin.

Outro

‘The world is yours’ indeed. Ironic because it never is…

[Published in the Business & Financial Times (B&FT) - 11th November, 2021]

Lay KPMG audit report on SML-GRA contract before Parliament – Isaac Adongo tells...

Lay KPMG audit report on SML-GRA contract before Parliament – Isaac Adongo tells...

Supervisor remanded for stabbing businessman with broken bottle and screwdriver

Supervisor remanded for stabbing businessman with broken bottle and screwdriver

NDC watching EC and NPP closely on Returning Officer recruitment — Omane Boamah

NDC watching EC and NPP closely on Returning Officer recruitment — Omane Boamah

Your decision to contest for president again is pathetic – Annoh-Dompreh blasts ...

Your decision to contest for president again is pathetic – Annoh-Dompreh blasts ...

Election 2024: Security agencies ready to keep peace and secure the country — IG...

Election 2024: Security agencies ready to keep peace and secure the country — IG...

People no longer place value in public basic schools; new uniforms, painting wil...

People no longer place value in public basic schools; new uniforms, painting wil...

'Comedian' Paul Adom Otchere needs help – Sulemana Braimah

'Comedian' Paul Adom Otchere needs help – Sulemana Braimah

Ejisu by-election: Only 33% of voters can be swayed by inducement — Global InfoA...

Ejisu by-election: Only 33% of voters can be swayed by inducement — Global InfoA...

Minority will expose the beneficial owners of SML, recover funds paid to company...

Minority will expose the beneficial owners of SML, recover funds paid to company...

Prof. Opoku-Agyemang has ‘decapitated’ the NPP’s strategies; don’t take them ser...

Prof. Opoku-Agyemang has ‘decapitated’ the NPP’s strategies; don’t take them ser...