Indigenous and protected parts of the Amazon rainforest seen as an important buffer against climate change are emitting previously undetected amounts of carbon, scientists say.

The researchers used advanced satellite imaging technology to measure and analyse emissions caused by forest degradation and disturbance, as well as by deforestation.

Their study, published Monday in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, found that indigenous and protected lands emitted almost a half billion tons of carbon, with forest degradation and disturbance accounting for more than 75 percent of losses in seven of the Amazon region's nine countries.

However, the study also revealed the vast majority of lost carbon comes from non-protected parts of the Amazon – reinforcing the crucial contribution that indigenous people make to limiting climate change.

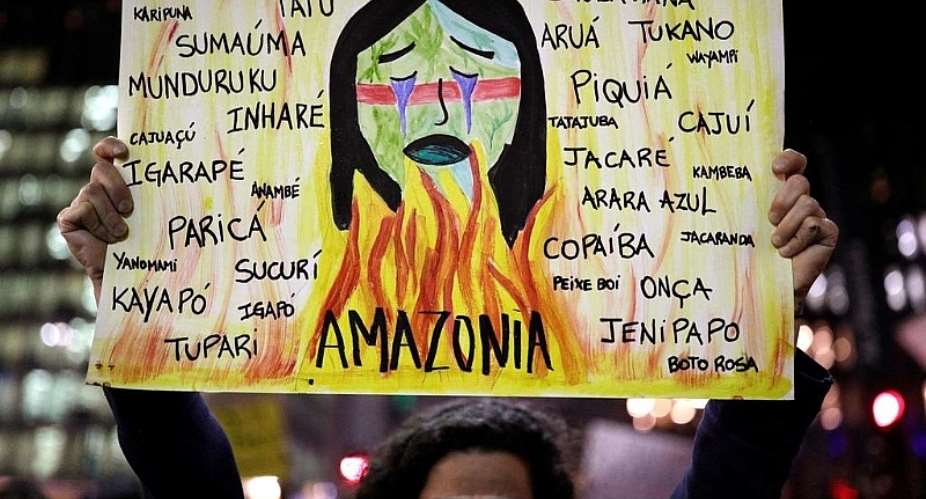

Illegal activities and growing weaknesses in the rule of law is putting protected lands at risk, the report says, especially as global demand for mineral wealth, fuel and commodities grows.

De facto guardians of the forest

For the last 15 or 20 years indigenous territories, usually in the more remote parts of the forest, have been actively keeping out groups looking to clear the land for cattle or other uses, explains David Kaimowitz, an expert on forests and conservation.

“When they have title from the government, or other types of support, they've been able to keep that deforestation out pretty effectively,” he says.

Over the past few years, however, that support has been waning in tandem with the growing threat of forest fires, which in turn are making the forest drier.

The study's authors want governments to urgently ramp up support for indigenous peoples, and to enforce existing laws protecting forests.

“While these indigenous communities have been protecting the forest very well, the threats are growing and so now the response has to grow as well,” Kaimowitz says.

“That's why the authors of this paper are calling for much stronger action to title the indigenous territories that still don't have title, to help the ones that do keep out groups coming to destroy their forest, and to help indigenous people have the livelihoods they need to keep their forest intact.”

While the Amazon is often referred to as “the lungs of the world” and is seen as a hedge against climate change, recent years have shown that human activity has altered the forest to the point where it's becoming an emitter of carbon, rather than a carbon sink.

Protected lands contribute far fewer emissions

Indigenous lands and protected areas make up 52 percent of the forest, and store 58 percent of its carbon. However, their net emissions are low, researchers say, accounting for just 10 percent of the region's lost carbon.

“Our findings suggest that ITs (indigenous territories) and PNAs (protected natural areas) were more effective than other land in maintaining their overall stock of carbon intact,” explains co-author of the study Carmen Josse, scientific director of Ecuador's Fundación EcoCiencia.

“In most countries, ITs and PNAs were either at or near net zero emissions, ranging from a small net source in Brazil to a small net sink in Peru.

“But with deforestation outside ITs and PNAs growing rapidly, our findings on the impact of degradation and disturbance suggest that significant, sustained support for indigenous people is now an urgent priority.”

Election 2024: Ghanaians will vote to erase Akufo-Addo’s horrifying legacy – Nii...

Election 2024: Ghanaians will vote to erase Akufo-Addo’s horrifying legacy – Nii...

BP killed ex-Weija-Gbawe MCE – Tina Mensah reveals

BP killed ex-Weija-Gbawe MCE – Tina Mensah reveals

Limited voter registration exercise: NDC slams EC over mass technical challenges

Limited voter registration exercise: NDC slams EC over mass technical challenges

UK, America will one day come to Ghana to borrow Akufo-Addo to be their presiden...

UK, America will one day come to Ghana to borrow Akufo-Addo to be their presiden...

EOCO returns fire at OSP over Cecilia Abena Dapaah’s money laundering case

EOCO returns fire at OSP over Cecilia Abena Dapaah’s money laundering case

Anti-corruption endeavours must be rooted in systems, investigations and prosecu...

Anti-corruption endeavours must be rooted in systems, investigations and prosecu...

We’ve not introduced 1% cybersecurity levy on banking transactions – BoG

We’ve not introduced 1% cybersecurity levy on banking transactions – BoG

EU hits out at sidelining of Chad election observers

EU hits out at sidelining of Chad election observers

‘Be calm; we’re having engagements on new fee implementation’ — KNUST SRC assure...

‘Be calm; we’re having engagements on new fee implementation’ — KNUST SRC assure...

Bawumia is compassionate, unique politician without corruption tag — Miracles Ab...

Bawumia is compassionate, unique politician without corruption tag — Miracles Ab...