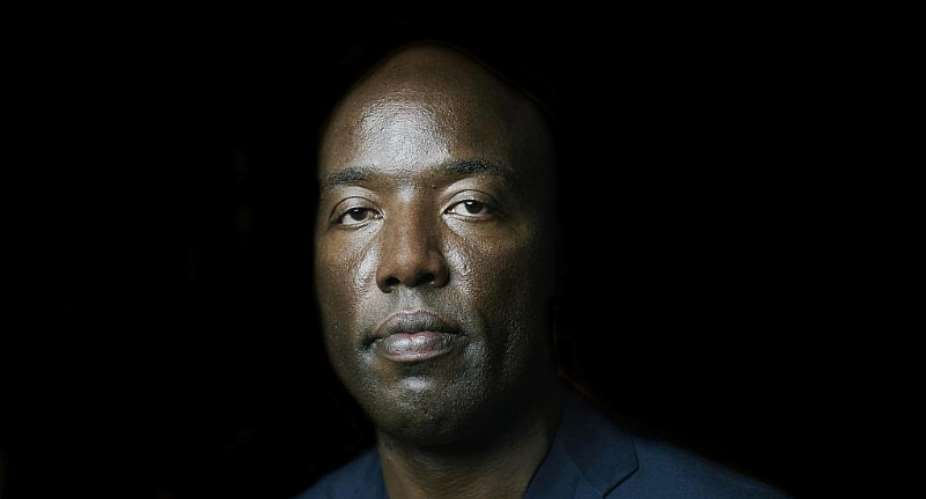

A former death row prisoner has spoken out against capital punishment on the 17th World Day against the death penalty, saying it deprives convicts of contrition. Pete Ouko was sentenced to death in Kenya for alleged murder in 2001. Now free, he is fighting to end the death penalty everywhere.

Pete Ouko remembers the day he was sent behind bars.

"Twenty one years ago, my wife was found killed outside a police station," he told RFI on Thursday as the world gathered to mark World Day Against the Death Penalty.

"I got a call about it, I went to the police station to be told what had happened. Some people decided to say I should be locked in, some people who were related to me. And that's the genesis of my being in prison," he said.

Ouko was charged with murder and sentenced to death, but has always mantained his innocence.

"We were working with a very corrupt criminal justice system," he comments.

"There are cases where judges never used to write judgments, they would get money from persons in court that are facing them, they write the judgment and they just bring for the judge to sign (…) Kenyans lost faith in the justice system."

But Ouko never lost his faith.

"I didn't believe for any moment that I was going to die for something I didn't commit. (...) Everyday I would wake up and say I'm going home the next day. So I kept hope alive and I focused on my kids. I said to myself these kids don't have parents right now, how do I get to see them again?"

Cleaning up justice system

The judge who tried Ouko would become the first judge to be sacked for corruption in 2003, as Kenya set about overhauling its justice system.

"Things have changed. We now have judges who take the government to court," says Ouko of the surprise decision in 2017 by the Supreme Court to overturn President Uhuru Kenyatta's election victory.

"We've had rulings even against the mandatory nature of the death penalty in Kenya," continues Ouko.

"Previously judges were told their hands were tied. If they found you guilty of the slightest offence under the penal code, they would sentence you to death. Today, judges have the discretion to make sentences as they deem fit."

The prison reform advocate hopes that Kenya, which currently has a moratorium on the death penalty, will eventually scrap it altogether.

"I know it's only a matter of time before it's over and done with".

Dangerous game

Some 170 countries have either abolished capital punishment or suspended it.

But UN figures show 23 countries have carried out at least one execution in the past decade.

Twelve African countries still retain the death penalty, with sub-Saharan states leading the way.

In most cases, the choice to keep the policy is "political" reckons Ouko, although warns it's a dangerous game.

"Look at Egypt, look at Sudan. The presidents are now behind bars. Now they're facing the death penalty themselves."

For the former death row prisoner, who today runs a charity to keep young people out of crime, capital punishment does not help convicts or victims.

"It's retributive but it doesn't solve the problem. The problem is if there are crimes that are being committed, that person who is committing that crime needs to be corrected. That person needs to know they've done something wrong and that they can change. I believe in second chances."

Second chances

Ouko was given a second chance in 2016, when he was pardoned by the president.

"I took a leap of faith and wrote to President Uhuru. I told him 'Sir, I don't agree with the decision of the court but I respect it. I've not attended any of my kids' graduations or plays, and now they're graduating, as a parent, I shouldn't miss this'".

On October 2016, Kenya commuted the death sentences of all 2,747 prisoners on the nation's death row, including Ouko's.

Since his release, the ex-prisoner has campaigned to end the death penalty in Kenya and around the world to prevent a potential miscarriage of justice.

"We need to give people a second chance, and I say that from what I saw in prison. In prison, people who had committed crimes would say I'm sorry I've done this, I need a second chance to make things right."

"When somebody is down, you don't continue hitting them, you help them to rise up again," he said.

Election 2024: Ghanaians will vote to erase Akufo-Addo’s horrifying legacy – Nii...

Election 2024: Ghanaians will vote to erase Akufo-Addo’s horrifying legacy – Nii...

BP killed ex-Weija-Gbawe MCE – Tina Mensah reveals

BP killed ex-Weija-Gbawe MCE – Tina Mensah reveals

Limited voter registration exercise: NDC slams EC over mass technical challenges

Limited voter registration exercise: NDC slams EC over mass technical challenges

UK, America will one day come to Ghana to borrow Akufo-Addo to be their presiden...

UK, America will one day come to Ghana to borrow Akufo-Addo to be their presiden...

EOCO returns fire at OSP over Cecilia Abena Dapaah’s money laundering case

EOCO returns fire at OSP over Cecilia Abena Dapaah’s money laundering case

Anti-corruption endeavours must be rooted in systems, investigations and prosecu...

Anti-corruption endeavours must be rooted in systems, investigations and prosecu...

We’ve not introduced 1% cybersecurity levy on banking transactions – BoG

We’ve not introduced 1% cybersecurity levy on banking transactions – BoG

EU hits out at sidelining of Chad election observers

EU hits out at sidelining of Chad election observers

‘Be calm; we’re having engagements on new fee implementation’ — KNUST SRC assure...

‘Be calm; we’re having engagements on new fee implementation’ — KNUST SRC assure...

Bawumia is compassionate, unique politician without corruption tag — Miracles Ab...

Bawumia is compassionate, unique politician without corruption tag — Miracles Ab...