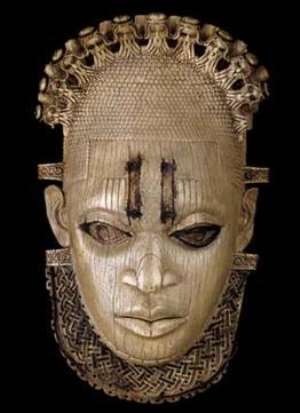

Queen-mother Idia, Benin/Nigeria, now in the British Museum. (1)

Seized by the British during the invasion of Benin in 1897.

Will she ever be liberated from the British Museum?

Normally, in cases of claims for stolen property or illegally detained objects, it is sufficient for the owner to establish beyond reasonable doubt that he is the rightful owner of the object in dispute and that the present holder of the object has no lawful right to the object. The present holder of the object then has to establish his right e.g. that he bought the object lawfully from a third party.

In the case of request for restitution of stolen objects in the British Museum, the situation has been radically changed by the British Museum, the British Government and the British Parliament. The question of legal ownership is not even posed. The fact that the object belonged to you or your family or community is rendered irrelevant. The question which is fundamental to all claims of property, the legal right to ownership, has been displaced and the main question here is not whether you have a legal right to the object but whether the British Museum can afford to dispense with the object in question i.e. whether it can and will de-accession the object. This issue came up in a recent exchange of correspondence between Toyin Agbetu, Head of Social and Education Policy, The Ligali Organization, London, and Neil MacGregor, Director, British Museum, London.

In answer to Toyin Agbetu’s request for the repatriation of stolen African objects in the British Museum, Macgregor referred him to the museum’s policy on de-accession (2). MacGregor also added that: “We are only able to consider requests from a representative body, such as a national government. We have never received a request for the repatriation of any artefacts in our collection from an African government.”

Some of the provisions in the policy document attached to MacGregor’ letter seem to us to deserve comments and careful study by Africans and others who are interested in the question of restitution of stolen African cultural objects now lying in their thousands in the depots of the British Museum in London and elsewhere.

The preamble of the policy document mentions at the beginning the acquisitions in the collection of the British museum that are covered, by purchase, gift or fieldwork. There is no mention of acquisition by way of loot, booty or conquest. However, by all standards and common consent, most of the objects in the British Museum have been acquired as booty, by looting or conquest. Since there is no mention of these modes of acquisition, one may presume that those illegal modes of acquisition come under fieldwork. Paragraph 2.1 however makes clear that objects acquired in controversial circumstance are also covered. The policy set in the document covers “other disposal (including disposal in response to any third-party claim for restitution or repatriation of an object in the Collection.”)

Paragraph 3.3 of the document states that the museum will not dispose of objects unless (a) the object is a duplicate of another object held in the collection, or (b )in the opinion of the Trustees the object is unfit to be retained in the Collection and can be disposed of without detriment to the interest of the public or scholars; or (c) it has become useless for the purposes of the Museum by reason of damage, physical deterioration, or infestation by destructive organism. These provisions are really remarkable. What do they mean or imply?

(a) object is a duplicate of another object held in the museum

It is extremely rare that a museum such as the British Museum has a duplicate of an object already in the museum. Mostly, the objects are unique even though there may be similar ones. As far as African cultural objects are concerned, they are mostly unique. On this ground alone, hardly any Africa object in the British Museum could be released. In any case, how does a claimant know that there is a duplicate in the British Museum since most of the African objects are kept in depots and there is no readily available document or catalogue listing all the items in the museum? It seems most museums do not want their public to know too much about what they have. So even if one were to accept this provision, it would be only the British Museum which could verify and certify its application. In any case only the Museum and not another party decides this issue. For the outside claimant, this provision is unhelpful. The British Museum once sold some Benin bronze works to Nigeria on the ground that they were duplicates. Years later they expressed the view that they had been mistaken in their assessment and that the works sold were originals and not duplicates. (3)

(b) in the opinion of the trustees the object is unfit to be retained in the Collection and can be disposed of without detriment to the interest of public or scholars

There will hardly be a stolen African cultural object that could be said to be unfit to be retained in the museum where they have been for hundreds of years after having been secured through wars and bloodshed. What the interest of the public is, will be determined by the British Museum. Scholars of African culture, especially those who have spent a life time in studying a particular people or culture can easily demonstrate that the removal of a particular object from the museum would hinder their research and publications. The general interest of scholars and students will also prevent such a finding of unfitness as paragraph 3.5 of the document makes clear. So this provision is also not very helpful for any claimant. In any case, if the object is unfit to be in the museum, the policy requires that the object “shall be disposed of in a way that prevents it being rediscovered and mistakenly reinterpreted.” Even at this point, the British Museum claims a monopoly of interpretation. So Africans will have to contend with interpretations of their culture from the British Museum even if they managed, in an improbable constellation of facts, to recover some of their stolen cultural objects released for being unfit in the museum.

(c) it has become useless for the purposes of the Museum by reason of damage, physical deterioration, or infestation by destructive organism

Who would want an object that has become useless through damage or deterioration? And how often will highly paid museum officials agree that cultural objects in their care have become useless due to damage or deterioration? This provision is also not very helpful for a claimant for restitution.

Paragraph 3.9 of the document emphasizes the “Trustees shall regard deaccession as a last resort that will only be considered if they regard it as the only fair and sufficient response to the claim.” Even in the exceptional case when de-accession is decided, the document provides that “the object should be transferred to another institution within public domain rather than to private individuals or organizations (particularly where there is a risk that the object will be reburied, disappear or be destroyed).” When one considers the nature of many religious and ceremonial or festive African objects, one can see the difficulty here. There are some religious objects which were not meant to be seen by the uninitiated or were meant to be seen only once in a while. What do we do, should we manage to get them back from the British Museum? The museum requires us to keep it in a public museum. What about if there is no museum at all in the area, as is the case in many African towns and villages? So even at this point, the British Museum is not willing to relax its control over a stolen cultural object which the owner has recovered. It pretends to have a God-given duty to watch over how other peoples use their cultural objects!

A quick consideration of the policy document shows that there is no serious intention on the part of the British Museum to consider demands for restitution nor on the part of the British Parliament which passed The British Museum Act 1963 which is alleged to be the basis of such a policy that allows the museum the greatest and widest freedom to decide when it will release objects in its collection, irrespective of how the objects got onto its inventory. For obvious reasons, no exception is made for stolen or looted objects. The British Government which was responsible in the first place for the massive looting of African art objects, appears to be satisfied with such an act which it passed in 1963, shortly after the independence of most African countries. Most of these African cultural objects should have been transferred with the transfer of power to the Independent Government as part of the right of the people to exercise self-determination in the cultural area. By retaining looted or stolen cultural objects, the colonial power has confiscated part of the independence it appeared to be granting. It is a pity that those who negotiated our Independence did not seem to attach much importance to our stolen cultural objects or were not in a position to secure their return.

In his letter of 20th July 2007 to Toyin Agbetu, Neil MacGregor states that the British Museum can only consider request from representative bodies such as a national government. However in the attached policy statement, there is no mention of such a requirement. Presumably, the basis for this requirement is to be found elsewhere. Should the British Museum not clearly indicate to Toyin Agbetu this very important condition which is not mentioned in the policy document? What else is missing in the policy document? Or should one find this out after going through with other conditions? Is this a way of wearing out the claimant?

MacGregor does not go into the demands of Toyin Agbetu except to seek his agreement that “there are no easy answers to the great questions of history from the 19th and 20th centuries”. MacGregor refers to “a representative body such as a national government”. Does this exclude other authorities such as kings and queens of Africa who were robbed of their cultural objects by the British? What about Benin, would they not accept a request from the Oba of Benin or could this only be accepted from the Nigerian government? Surely, the British Museum should enlighten its clients, that is, if Pan African Organizations, such as The Ligali Organization, are also included in the clients of a museum which pretends to hold stolen cultural objects on behalf of humanity.

It is remarkable that the British Museum, a British institution created by a British act of parliament, not an international or universal museum as the director and his supporters sometimes try to make us believe, can declare that it only deals with national governments. With all due respect, there is nothing in International Law to support such pretence from a national institution. If the museum has in its collection stolen items, such as the Benin Bronzes, there will be no justification for refusing to consider a claim from the Oba of Benin. In any case when the items were stolen, Benin was a sovereign State.

MacGregor mentions that “We have never received a request for repatriation of any artefacts in our collection from any African government”. Does “we” include the British Parliament to which the Oba of Benin has sent a formal request (4) or does the British Museum take the position that requests to the British Parliament do not concern the British Museum? So when you go to the British Parliament it sends you to the British Museum and when you go to the British Museum it says you are not a “national government”? With such cheap tricks one could try to avoid all African claims for restitution since most of the States in existence at the time of British invasion and colonization no longer exist as national States. So the African peoples lose their claims for stolen cultural objects?

With this policy of the British Museum, it is no wonder that no self-respecting African government is willing to submit itself to dealing with the museum as regards the restitution cases. Such requests will be futile given the stated policy of the museum. For example, in a case involving Nazi Era-looted drawings seized by the Gestapo from a Dr. Feldmann and which ended at the British Museum in 1946-1949, it was said that under UK law the British Museum could not deaccession unique art works. (5) Most African art works are unique. This is remarkable. All parties to the case acknowledged the fact that the art works in question had been wrongfully confiscated by the Nazis and yet the British authorities were unwilling to return the stolen objects on the ground that this was not possible under English Law. Could the Court not have reasoned that Parliament surely did not intend to approve wrongful acts of the Nazis against whom the sons and daughters of the land had to sacrifice their lives and that there was a presumption that Parliament does not intend to act against common morality and International Law which have condemned Nazism and its evil acts? Once again, it seems that where British material interests are involved public morality and International Law are not really relevant. It is interesting to know that in Austria when a museum or art gallery is found with Nazi-stolen art objects, everybody gets involved and the museum is put under considerable pressure from all sides to either return the object to the owners or find a solution acceptable to the owners. It seems in accepted in Great Britain that nothing can be done about Nazi-looted objects once they enter the British Museum.

That the British Museum will do every thing except de-accession is further illustrated by the extraordinary handling of the Ethiopian tabots in the museum in 2004.These tabots are part of the large number of treasures the British Army looted when Britain invaded Maqdala, then Ethiopian capital, in 1868. during a punitive expedition. According to the Art Newspaper, the museum director, Neil MacGregor decided that no one, not even he, should see the tabots which the Ethiopians consider to be the original Ark of the Covenant which contained the Ten Commandments.

The tabots are not supposed to be seen by anyone except the senior clergy of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church. The tabots were moved from a British Museum depot in Hackney, London to a special room in the basement of the main museum building in Bloomsbury, London:

“They were carried by a senior member of the Ethiopian church in Britain and were covered during the transportation. Once inside the special room, and alone, the priest placed the tabots, wrapped in cloth, on a shelf covered with conservation-quality purple velvet. No museum staff, not even curators or conservators, are permitted to enter the locked room.

It is, of course, somewhat pointless for a museum to hold objects that can never be seen by scholars, let alone by the general public. Delicate discussions are therefore underway for a long-term solution. The BM has begun discussions which could lead to the loan of the tabots to the Ethiopian Orthodox church in London, possibly on a renewable five-year basis.

The tabots would then be housed securely in the London church, where they would remain out of view. A loan would avoid the legal constraints on deaccessioning by the BM. It is also evident that keeping the tabots in the UK would avoid problems that might arise from a loan to Ethiopia, since there could well be pressure to retain these tabots indefinitely.” (6)

The British Museum was prepared to follow instructions and prescriptions relating to the sacred nature of the tabots, the Director of the Museum visited Addis Ababa and was prepared to consider a loan, not to the Ethiopian Orthodox Church in Ethiopia, but to the Church in London. Clearly, there was a will to do everything except the right and simple thing: return the tabots to the rightful owners in Ethiopia.

Why keep African cultural objects for which the British have no practical or religious need and which cannot be shown to the public? Where then are the pretences to inform or educate the public about the cultures of the world? Where then are the pretences of the “universal museums” for which MacGregor, Cuno and Philippe de Montebello seem ready to sacrifice all moral principles? De-accessioning seems to be a sacred taboo for the British Museum. So what was the Director trying to convey to Toyin Agbetu in his letter with a document on the de-accession policy of the museum? Openness and frankness everywhere except in the British Museum? What kind of morality and service to humanity does this approach reveal?

The unwillingness of the British Museum is partly explained by the fear to set a precedent since there are thousands of precious treasures from many African countries, including Ethiopia that are in various British institutions, such as the very respectable universities of Oxford, Cambridge and Edinburgh and the venerable museums -Victoria and Albert Museum, British Museum etc. A decision by one institution to return cultural objects will release, it is feared, an avalanche of demands for restitution of the stolen objects, some of which are alleged to be in the possession of the British Queen. But is such a fear a justification for not doing the correct thing?

University of Edinburgh seems to follow closely the British Museum in this matter and has also refused to return Ethiopian manuscripts. An Advisory Group set up to examine a request by AFROMET (Association for the Return of Maqdala Ethiopian Treasures) for the return of the manuscripts stolen from Maqdala recommended that the University should not accede to that request and recommended that; “every effort should be made, following discussion with AFROMET and the University of Addis Ababa representatives, to ensure that the manuscripts are accessible to the Ethiopian people and scholars through appropriate surrogates.” (7) The Advisory Group also recommended that the University of Edinburgh contribute microfilm copies of the manuscripts to the Institute of Ethiopian Studies at Addis Ababa. It appears that Ethiopia had paid the British Library £10,000 for microfiches Maqdala manuscripts. Is there no shame in the British cultural world? The report includes statements which surprised me and revealed the usual arrogance, hypocrisy and insensitivity; “Although there is a lack of clarity as to how precisely the manuscripts came to be in Magdala, the Advisory Group accepts that the Emperor Tewodros II (Theodorus) had gathered manuscripts from across Ethiopia and brought them to Magdala. The Advisory Group noted that the concept of the church was embodied in the Emperor and, as such, it is acknowledged that the original owner had therefore been Theodorus.” (8)

Did anybody, except the Advisory Panel, ever have any doubts that those treasures stolen by the British troops in 1886 from the palace of the Emperor Tewodros in Maqdala belonged to the Emperor?

The report mentions that it would be inappropriate to give any of the manuscripts to AFROMET although AFROMET had not asked for any manuscript to be given to it. It requested the University to consider whether it would not be appropriate for such manuscripts to be returned to their country of origin: Ethiopia. The report goes on to say that items similar to those held by the University of Edinburgh also exist within Ethiopia and that no evidence was presented to suggest that those manuscripts in Edinburgh are objects of major cultural, religious or scientific importance.

The usual arguments and insinuations based on alleged conservation and security grounds are also advanced or hinted at in the Edinburgh report. As I have already demonstrated in several articles, the conservation and security arguments of the British museum and other holders of illegal cultural property are dishonest, baseless and hypocritical. Who looked after these manuscripts and objects before the British military invasion in Maqdala? The Ethiopians had preserved these manuscripts and other precious objects for centuries before they were brutally removed by the British invasion army. A British institution now tells the Ethiopians you cannot look after your manuscripts and it is better they are kept in Europe. Against a determined and aggressive British army, few countries can protect their cultural property. Supposing the British Army decided to attack the Hofburg , Vienna, Austria, for the many cultural items there, would anybody guarantee afterwards that the Austrians will able to look after their cultural objects? This is what happened to Ethiopia and to Benin.

The dishonest and self-serving arguments statements are coming from University people dealing with the precious manuscripts relating to the history of an African people. How would the British scholars feel if they had to go to Accra, Addis Ababa, Timbuktu or Harare to consult basic and important documents concerning their history and culture? The statements in the report create an impression as if the Ethiopians were asking for some kind of assistance from the University. The Edinburgh scholars do not seem to be conscious that they are dealing with a nation that is asking for the return of its cultural objects stolen by Britain. With the way of reasoning of the Edinburgh scholars nothing will ever get out of Edinburgh or London.

What the African governments should do is to approach directly the British Government. It is the correct counterpart for dealing with matters between the African States and Britain and not the British Museum. Moreover, most of the stolen items were confiscated or looted by the British Army acting on instructions and on behalf of the British Government and the Head of the British State. Here lies the responsibility for ensuring the return of our cultural objects and not the British museum which is an internal institution of the British Government and Parliament. The Museum may pretend to be independent of the British Government and the British Parliament. But an examination of the appointment of the Trustees of the museum clearly indicates who their masters are. The twenty five Trustees of the British Museum are appointed as follows: one by the Queen, fifteen by the Prime Minister, four by the Secretary of State, and five by the Trustees of the British Museum. There is no way the Trustees can deny that they act in the interest of the British Government and, perhaps people. (9) Certainly, they do not act in the interest of mankind or of the African peoples. They are governed by a British legislation and not an international convention.

It seems evident from what has been said above that once a valuable or unique art object enters the inventory of the British Museum, there is no way it can be removed or will be removed from its inventory. The British Parliament, the British Museum and the British Courts seem to work together to make restitution very difficult if not impossible. If one cannot recover art objects stolen by the Nazis then it seems excluded that one can recover cultural objects stolen by the British.

The British Museum which has some 13 million objects on its inventory does not appear to be prepared to dispense with a few no matter how immoral and illegal their provenance. So what was Neil Macgregor, Director of the British Museum trying to convey to Toying Agbetu? Why did he not tell him straight away that there was no way, under present British Law, to recover the stolen African cultural objects and that only a request from African Governments addressed to the British Government may have a chance of success if this leads to a change in the present governing act of the museum, The British Museum Act, 1963? Or are honesty and frankness not part of the requirements of the position? Knowingly given misleading or useless advice and information comes close to not conveying the truth.

Dr. Greenfield has succinctly sumarized the position of the British Museum as follows:

“The museums’s official position on claims for the return of cultural property has been understandably defensive. The line taken has always been that legislation has prohibited it from permanently disposing of any object, than duplicates, and that its aim is to preserve exhibits “for the benefit of international scholarship and the enjoyment of the general public.” (10)

Kwame Opoku, 11 May, 2008.

NOTES

(1) This ivory hip mask represents an image of the Queen Mother Idia, mother of Oba Esigie, who ruled Benin in the 16th century. Another Idia hip mask is in the Metropolitan Museum of Art,New York. This mask has become a symbol of Pan Africanism and was used as the official logo of FESTAC 77, an African cultural festival. When the Nigerian Government requested the British to lend the mask for the purposes of the African festival the British refused. After all kinds of excuses, that the mask could not travel, they asked for a high insurance premium which the Nigerians were willing to pay but the British refused finally. This great disrespect to the people of Benin, all Nigerians and the entire continent of Africa has not been forgotten but apparently the British Government does not care. I have no sign or information that such an insult will not be repeated. It would have been a magnificent opportunity to make some amends, albeit small, if the British Parliament had passed a law immediately after this disgraceful refusal to make the return of Queen-mother Idia possible.

An interesting comparison of the two Idia ivory masks has been made by the

Comprehensive Business and Investment Data on Nigeria www.marketsandinvestments.com/images/mask2

The 16th century mask at the heart of our logo has its roots in the ancient city of Benin, in modern day Edo State of Nigeria. It represents the Queen Mother IDIA, mother of Oba Esigie who ruled the Benin Kingdom at the time. It is one of two near identical masks taken to Britain by Sir Ralph Moore K.C.M.G, Counsel General of the Niger Coast Protectorate, following the British Punitive Raid on Benin in 1897. It was bought by a Professor Seligman in 1909, from a relative of Sir Ralph Moore to whom it passed on his death, and later passed to the British Museum where it is displayed to this day.

In 1977 it was used as the symbol for FESTAC 77, The 2nd Black and African Festival of Arts and Culture, hosted by Nigeria. Between 1979 and 1992 it featured on the back of Nigeria’s One Naira Note. In 1996 we adopted it at the heart of our logo to convey Nigeria’s unique heritage … and our depth of understanding of the Nigerian market.

|  |

| On display at the Metropolitan Museum, New York, USA. | On display at the British Museum, London, |

After the British refusal to lend the original 16th century Idia pendant mask, the Nigerian authorities set about to find an alternative; they obtained a replica of the ivory pendant made by Joseph Alufa Igbinovia which was subsequently presented to the Head of State of Nigeria as the symbol of FESTAC 77. As Peju Layiwola stated:

“The refusal of the loan and the following public discussion in Nigeria contributed to the fact that this mask became one of the most reproduced African artworks and a powerful icon for African culture and history”

(Adepeju Layiwola, in Barbara Plankensteiner (Ed) Benin Kings and Rituals: Court Arts from Nigeria ,Snoek Publishers. 2007, p.505).

Third Mask

FESTACT 77 emblem (replica, 1977)) by Alufa Igbinovia, pending return of the original from the British Museum. The National Commission for Museums and Monuments, Nigeria

The third mask, by Alufa Igbinovia, has served as temporary replacement for the original 16th century carving, whilst waiting for the return of the original from the British Museum. In the unlikely case that the British realize the mistake they have made and in a desire to make amends for the insult to the African peoples, they return the original mask, we would expect an official celebration of the homecoming of this most beloved symbol of Pan-Africanism. But do colonialists ever learn and regret their grave mistakes? Have they ever apologized for slavery and all the atrocities they committed? We have to be realistic and go by historical experience.

(2) See Annex I.

(3) “British Museum Sold Benin Bronzes” http://www.forbes.com/)

(4) See Annex II.

(5) See Annex III Two British museums pay compensation to keep Nazi-loot http://www.theartnewspaper.com/;

(6) http://www.assatashakur.org/

(7) University of Edinburgh-Report of Advisory Group-Ethiopian Manuscripts

(8) Ibid.p.3

(9) The governance of the British Museum has been described as follows:

In technical terms, the British Museum is a non-departmental public body sponsored by the Department for Culture, Media and Sport through a three-year funding agreement. Its head is the Director. The British Museum was run from its inception by a 'Principal Librarian' (when the book collections were still part of the Museum), a role that was renamed 'Director and Principal Librarian' in 1898, and 'Director' in 1973 (on the separation of the British Library).[32]

A board of 25 trustees (with the Director as their accounting officer for the purposes of reporting to Government) is responsible for the general management and control of the Museum, in accordance with the British Museum Act of 1963 and the Museums and Galleries Act of 1992.[33] Prior to the 1963 Act, it was chaired by the Archbishop of Canterbury, the Lord Chancellor and the Speaker of the House of Commons. The board was formed on the Museum's inception to hold its collections in trust for the nation without actually owning them themselves and now fulfil a mainly advisory role. Trustee appointments are governed by the regulatory framework set out in the code of practice on public appointments issued by the Office of the Commissioner for Public Appointments. For a list of current trustees, see here. See http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/British_Museum

(10) Jeanette Greenfield, The Return of Cultural Treasures, Cambridge University Press, Third Edition, 2007, p.103

ANNEX I

FROM THE DIRECTOR

Mr Toyin Agbetu

Head of Social and Education Policy

The Ligali Organisation

PO Box 1257

London

E5 OUD

20th July 2007

Thank you for your letter of 21st June and for setting out the historical and cultural background to heritage issues in Nigeria as you see them. Perhaps we can agree on one thing: that none of this is simple or straight forward, and that there are no easy answers to the great questions of history fromthe 19th and 20th centuries.

I would like to address some of the points you make in your letter, in particular your assertion that I was unwilling to meet with you. As stated in my previous letter, I offered to rearrange my schedule at very short notice on the day that you were in the Museum in order to meet with you, however you declined this offer.

With regard to your request for the repatriation of African artefacts I would refer you to our policy on de-accession, of which I have enclosed a copy.

This can also be found on our web site at the following URL

www.thebritishmtiseum.ac.uk/the_museum/about_us/management_and_governance/museum_governance.aspx

We are only able to consider requests from a representative body, such as a national government.

We have never received a request for the repatriation of any artefacts in our collection from an African government.

As you know, the British Museum is working with overseas museums and

institutions – including those in Nigeria – in a way in which the collections held in trust at the British Museum can be shared worldwide in the context of the universal museum. It is through such partnerships that we believe we are best able to promote public understanding of Africa's culture and history worldwide.

Neil MacGregor

Great Russell Street, London WC 1 B 3DG Telephone +44 (0)20 7323 8340 Facsimile +44 (0)20 7323 8480

[email protected] www.thebritishmuseum.ac.uk

BRITISH MUSEUM

POLICY ON DE-ACCESSION OF REGISTERED ITEMS FROM THE

COLLECTION http://www.britishmuseum.org/pdf/Deaccession.pdf

1. Preamble

1.1 This policy covers all objects registered as part of the collection of the British Museum, whether they were acquired by purchase, gift or fieldwork. This Policy should be read alongside The British Museum Policies on Acquisitions; Human

Remains; and Storage, Conservation and Documentation.

2. Purpose

2.1 This document sets out the policy of the Trustees of the British Museum on the exercise of their powers of de-accession from the Collection whether by sale,

exchange, gift and other disposal (including disposal in response to any third

party claim for the restitution or repatriation of an object in the Collection).

3. The Legal Duty and Powers of the Trustees

3.1 The British Museum Act 1963 ("the Act") is the governing instrument of the

Trustees of the British Museum.

3.2 Objects vested in the Trustees as part of the Collection of the Museum shall

not be disposed of by them otherwise than as provided by the Act'. Therefore

the Trustees' power to de-accession objects from the Collection is limited and

there is a strong legal presumption against it.

3.3 Decisions to dispose of objects comprised within the Collection cannot be made with the principal aim of generating funds though any eventual proceeds from such disposal must be used to add to the collection'. The Trustees do not have the power to sell, exchange, give away or otherwise dispose of any object vested in them and comprised in the Collection3 unless (a) the object is a duplicate of another object held in the collection,

ss 3(4) ibid

2 Where an object has been acquired with the aid of an external funding organisation, any conditions

attached to the original grant will be followed including the repayment of the grant if appropriate 3 ss

3(4) ibid

or (b) in the opinion of the Trustees the object is unfit to be retained in the Collection and can be disposed of without detriment to the interests of the

public or scholars4;

or (c) it has become useless for the purposes of the Museum by reason of 52 damage, physical deterioration, or infestation by destructive organisms

3.4 Objects that are duplicates: The Trustees do not normally de-accession duplicate objects from the Collection unless they are identical in all material respects (see

3.9 below).

3.5 Objects that are "unfit". The Trustees would not normally consider that an

object that has been added to the Collection could be regarded as "unfit".

Before concluding an object was unfit, the Trustees would have to be

satisfied that it could be disposed of without detriment to the interests of

students or the wider public.

3.6 Human Remains: See the Trustees Policy on Human Remains.

3.7. National Museums and Galleries: There exist limited powers 6 for the Trustees to transfer objects in the Collection, by way of sa7le , gift or exchange, to any of the listed institutions in the United Kingdom

3.8 The charitable status of the Museum: The Museum is an "exempt" charity8 and the Trustees are therefore subject to the English trust and charity law and the

supervision of the Attorney General/the Charity Commissioners in the exercise

of their legal powers and duties.

3.9 Procedures: In those exceptional cases where the Museum is legally free to

dispose of an item from the Collection, any decision to do so will be taken by

the Board of Trustees only after full consideration of the merits of the case by

reference to the principles set out above and on the basis of curatorial, legal and

other appropriate advice and authority. Where there is an external claim for

the de-accessioning of an object within the Collection, the Trustees shall regard

de-accession as a last resort that will only be considered if they regard it as the

only fair and sufficient response to the claim. Once a decision to dispose of an

object from the Collection has been taken, the Trustees would normally expect

that, in the absence of strong reason to the contrary, the 4 ss 5(1) ibid(nb: where an object has become vested in the Trustees by virtue of a gift or bequest these

powers of disposal are not exercisable as respects that object in a manner inconsistent with any condition attached to the gift)

5 under ss5(2) ibid

6 s 6 Museums and Galleries Act 1992.

7 Schedule 5, Museums and Galleries Act 1992

8 see section 3(5) and Schedule 2 paragraph (p) Charities Act 1993

object should be transferred to another institution within the public domain

rather than to private individuals or organisations (particularly where there is

a risk that the object will be reburied, disappear or be destroyed). Full records

will be kept of all such decisions and the items involved and proper

arrangements made for the preservation and/or transfer, as appropriate, of the

documentation relating to the items concerned, 3 including photographic

records where practicable.

3.10 Any object proven unfit for retention in this collection or other public

collections shall be disposed of in a way that prevents it being rediscovered

and mistakenly reinterpreted.

4. Assurance

In the annual assurance statement Keepers shall confirm that this policy is

understood and implemented by the staff in their departments

5. Review

This Policy will be reviewed from time to time and at least once every five years. In the event that significant changes to the Policy are made, every reasonable effort will be made to notify stakeholders, including the Council for Museums, Libraries and Archives.

This Policy was approved by the Trustees of the British Museum in 26 March 2004 and will be reviewed no later than 2009.

ANNEX II

Select Committee on Culture, Media and Sport Appendices to the Minutes of Evidence Appendix 21.

The Case of Benin

Memorandum submitted by Prince Edun Akenzua

I am Edun Akenzua Enogie (Duke) of Obazuwa-Iko, brother of His Majesty, Omo, n'Oba n'Edo, Oba (King) Erediauwa of Benin, great grandson of His Majesty Omo n'Oba n'Edo, Oba Ovonramwen, in whose reign the cultural property was removed in 1897. I am also the Chairman of the Benin Centenary Committee established in 1996 to commemorate 100 years of Britain's invasion of Benin, the action which led to the removal of the cultural property.

HISTORY

"On 26 March 1892 the Deputy Commissioner and Vice-Consul, Benin District of the Oil River Protectorate, Captain H L Gallwey, manoeuvred Oba Ovonramwen and his chiefs into agreeing to terms of a treaty with the British Government. That treaty, in all its implications, marked the beginning of the end of the independence of Benin not only on account of its theoretical claims, which bordered on the fictitious, but also in providing the British with the pretext, if not the legal basis, for subsequently holding the Oba accountable for his future actions."

The text quoted above was taken from the paper presented at the Benin Centenary Lectures by Professor P A Igbafe of the Department of History, University of Benin on 17 February 1997.

Four years later in 1896 the British Acting Consul in the Niger-Delta, Captain James R Philip wrote a letter to the British Foreign Secretary, Lord Salisbury, requesting approval for his proposal to invade Benin and depose its King. As a post-script to the letter, Captain Philip wrote: "I would add that I have reason to hope that sufficient ivory would be found in the King's house to pay the expenses incurred in removing the King from his stool."

These two extracts sum up succinctly the intention of the British, or, at least, of Captain Philip, to take over Benin and its natural and cultural wealth for the British.

British troops invaded Benin on 10 February1897. After a fierce battle, they captured the city, on February 18. Three days later, on 21 February precisely, they torched the city and burnt down practically every house. Pitching their tent on the Palace grounds, the soldiers gathered all the bronzes, ivory-works, carved tusks and oak chests that escaped the fire. Thus, some 3,000 pieces of cultural artwork were taken away from Benin. The bulk of it was taken from the burnt down Palace.

NUMBER OF ITEMS REMOVED

It is not possible for us to say exactly how many items were removed. They were not catalogued at inception. We are informed that the soldiers who looted the palace did the cataloguing. It is from their accounts and those of some European and American sources that we have come to know that the British carried away more than 3,000 pieces of Benin cultural property. They are now scattered in museums and galleries all over the world, especially in London, Scotland, Europe and the United States. A good number of them are in private hands.

WHAT THE WORKS MEAN TO THE PEOPLE OF BENIN

The works have been referred to as primitive art, or simply, artifacts of African origin. But Benin did not produce their works only for aesthetics or for galleries and museums. At the time Europeans were keeping their records in long-hand and in hieroglyphics, the people of Benin cast theirs in bronze, carved on ivory or wood. The Obas commissioned them when an important event took place which they wished to record. Some of them of course, were ornamental to adorn altars and places of worship. But many of them were actually reference points, the library or the archive. To illustrate this, one may cite an event which took place during the coronation of Oba Erediauwa in 1979. There was an argument as to where to place an item of the coronation paraphernalia. Fortunately a bronze-cast of a past Oba wearing the same regalia had escaped the eyes of the soldiers and so it is still with us. Reference was made to it and the matter was resolved. Taking away those items is taking away our records, or our Soul.

RELIEF SOUGHT

In view of the fore-going, the following reliefs are sought on behalf of the Oba and people of Benin who have been impoverished, materially and psychologically, by the wanton looting of their historically and cultural property.

(i) The official record of the property removed from the Palace of Benin in 1897 be made available to the owner, the Oba of Benin.

(ii) All the cultural property belonging to the Oba of Benin illegally taken away by the British in 1897, should be returned to the rightful owner, the Oba of Benin.

(iii) As an alternative, to (ii) above, the British should pay monetary compensation, based on the current market value, to the rightful owner, the Oba of Benin.

(iv) Britain, being the principal looters of the Benin Palace, should take full responsibility for retrieving the cultural property or the monetary compensation from all those to whom the British sold them.

March 2000

ANNEX III

Law prevents UK museum from returning stolen art: British Law Prevents Restitution of Stolen Art

Posted Sat May 28, 2005 12:00pm AEST

The British Museum is prevented by law from returning four Old Master drawings looted by the Nazis, even though it wants to hand them back to their Jewish owners' heirs, a judge has ruled.

Senior High Court judge Sir Andrew Morritt says that the 1963 British Museum Act, which protects the famous London-based institution's collections for posterity, could not be overridden.

Not even by a "moral obligation" to return works known to have been stolen.

The ruling was requested by Attorney-General Lord Peter Goldsmith, the Government's chief legal officer.

He had asked for clarification after warning that if there was a moral obligation to restore such objects it could give Greece a method by which to reclaim the Elgin Marbles.

The marbles are hundreds of marble sculptures taken from the Parthenon in Athens in 1801 and 1802 by British diplomat Lord Elgin, who later sold them to the British Museum.

Greece has long demanded the sculptures' return, something Britain is resisting.

Justice Morritt was asked to rule on the museum's obligation to return the four drawings by artists including Nicolo dell'Abbate and by Nicholas Blakey.

The paintings were stolen from the home of Dr Arthur Feldmann in 1939 when Germany invaded Czechoslovakia.

Dr Feldmann and his wife died at the hands of the Nazis, and the four drawings were acquired by the British Museum shortly after World War II.

A spokesman for the Commission for Looted Art in Europe, which is representing Dr Feldmann's heirs, says the judgement shows that Britain's Government should amend the law.

"The commission very much regrets that this avenue to achieve the return of the drawings is not now open to the museum," he said.

The museum agreed three years ago to return the artworks.

Minority will expose the beneficial owners of SML, recover funds paid to company...

Minority will expose the beneficial owners of SML, recover funds paid to company...

Prof. Opoku-Agyemang has ‘decapitated’ the NPP’s strategies; don’t take them ser...

Prof. Opoku-Agyemang has ‘decapitated’ the NPP’s strategies; don’t take them ser...

Abubakar Tahiru: Ghanaian environmental activist sets world record by hugging 1,...

Abubakar Tahiru: Ghanaian environmental activist sets world record by hugging 1,...

Prof. Naana Opoku-Agyemang will serve you with dignity, courage, and integrity a...

Prof. Naana Opoku-Agyemang will serve you with dignity, courage, and integrity a...

Rectify salary anomalies to reduce tension and possible strike action in public ...

Rectify salary anomalies to reduce tension and possible strike action in public ...

Stop all projects and fix ‘dumsor’ — Professor Charles Marfo to Akufo-Addo

Stop all projects and fix ‘dumsor’ — Professor Charles Marfo to Akufo-Addo

Blue and white painted schools will attract dirt shortly – Kofi Asare

Blue and white painted schools will attract dirt shortly – Kofi Asare

I endorse cost-sharing for free SHS, we should prioritise to know who can pay - ...

I endorse cost-sharing for free SHS, we should prioritise to know who can pay - ...

See the four arsonists who petrol-bombed Labone-based CMG

See the four arsonists who petrol-bombed Labone-based CMG

Mahama coming back because Akufo-Addo has failed, he hasn't performed more than ...

Mahama coming back because Akufo-Addo has failed, he hasn't performed more than ...