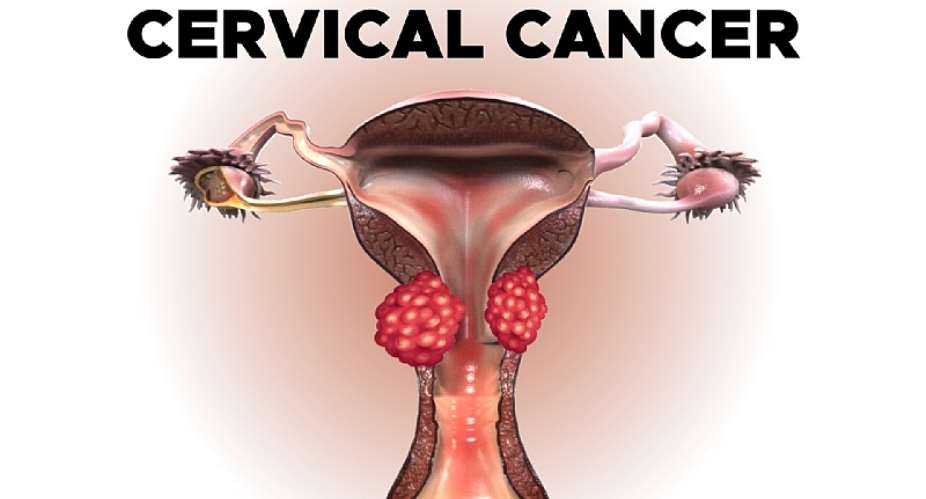

In 2022, Kenya’s population was 49.4 million of whom 16.8 million were women aged 15 years and above and at high risk of developing cervical cancer. Every year over 5000 women are diagnosed with cervical cancer, and more than 3000 die from the disease. 1,2 The majority of cervical cancer incidence and mortality still occurs in low- and middle-income countries, many of which are African. This demonstrates the inequities marked by the lack of access to national HPV vaccination programs, cervical cancer screening, and treatment services, driven by social, economic, cultural, and even personal barriers.2

Cervical cancer is not at the top of many people’s lists of hot discussion topics, yet HPV is the most common sexually transmitted infection in the world. Globally, both men and women have a 50% risk of being infected with HPV at least once in their lives, and the risk is highest in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), with an average of 24%.3 What makes these numbers even more shocking is that cervical cancer – is caused by persistent infection with the human papillomavirus (HPV) – can be prevented or treated, provided a vaccine has been administered or the cancer is detected early.2

Cervical cancer can affect anyone, regardless of their economic circumstances, and there is no shame in being tested – especially as our primary caregivers are most at risk. Oxfam’s 2019 Household Care Survey in Kenya found that women spent about five hours per day on care as a primary activity, compared to men who spent one hour. These are our wives, mothers, grandmothers, sisters, and aunts who, aside from being primary caregivers, also constitute almost 50% (49.7% in 2022) of the Kenyan workforce, so it makes both social and economic sense to protect them.4,5

In Kenya, while there is a National HPV Vaccination Program, data indicates that in 2021, only 31% of the primary targeted demographic – adolescent girls and young women (AGYW) – received the required two vaccine doses.2 In the past, getting screened for cervical cancer required a pap smear performed by a medical practitioner. Many women avoid this procedure because it is expensive and invasive. Feelings of embarrassment and, in some cases, cultural bias or stigma prevent women from going for the test. Thankfully, however, testing has evolved.

Today, the National Cancer Screening Guidelines of Kenya recommends Human Papillomavirus Screening (HPV) as the Primary screening tool for women above 30 years.9 HPV testing is based on the detection of DNA from high-risk HPV types in vaginal and/or cervical samples. Since persistent HPV infection is the cause of 99.7% of cervical cancer, a positive test result indicates that there may be an existing lesion or a risk of future precancerous and cancerous lesions.

A significant benefit of using HPV testing for Cervical cancer screening is that healthcare facilities can now provide women with HPV self-collection kits. These kits empower women to collect their own samples and submit them for testing. A further benefit is that HPV testing is now widely available as the testing is done on the same instruments established across Kenya for HIV testing. The convenience and privacy created by the self-collection kit is finally breaking barriers in the uptake of cervical cancer screening.

Let’s consider a working Kenyan woman in rural Turkana – a small-scale farmer and primary caregiver for her family. She goes to the clinic for her baby to be vaccinated and incidentally, the healthcare worker might suggest Visual Inspection with Acetic Acid (VIA) – the default testing method.

To be tested, she would have to leave the farm for the day. Arriving at the clinic, she waits to be assisted by a healthcare worker who is tending to over a hundred patients a day, making the experience laborious for both the patient and the healthcare worker. Self-collection addresses this problem twofold. A single healthcare worker can lighten their load by training several women at once to collect their own samples, significantly reducing the burden of time for both patient and healthcare worker. Once the women have collected their own samples, the samples can be aggregated and sent to the nearest HPV testing center and results returned within the shortest possible time.

Studies show that self-collected HPV-based cervix screening (SCS) is a feasible and cost-effective solution to addressing barriers to screening – especially in low-resourced and rural areas, and studies conducted throughout Africa on SCS uptake in local communities have been positive. For example, a recent study conducted in 16 villages throughout rural Uganda, using a door-to-door implementation method, resulted in 100% uptake from participants.6

Every family has a story about cervical cancer – perhaps a colleague who had to take time off work for treatment or a family member who had a hysterectomy to prevent cancer progression (this is common). Every survivor is here as a result of early diagnosis – and a living testament to the fact that cervical cancer can be avoided or treated successfully.

Public-private partnerships have made immense progress in eliminating cervical cancer. For example, the Go Further public-private partnership between PEPFAR, the George W. Bush Institute, the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS, Merck, and Roche is working towards ending AIDS and cervical cancer in Sub-Saharan Africa within a generation, by investing in partner countries to integrate and scale-up cervical cancer screening and treatment. But there is still so much work to be done, as mortality continues to rise across our continent.6

On the cusp of the recent adoption of the WHO Resolution on Strengthening Diagnostics Capacity, we have a framework that governments, policymakers, and private sector partners must work towards. The Resolution, while not mandated, acknowledges the value of diagnostics, urging government stakeholders to mobilize and significantly ramp up access to testing.

We have a responsibility to our primary caregivers – mothers, sisters, daughters, and partners – to change the statistics. Now is the time for the private and public sectors to come together to eradicate this preventable killer. We need a collective, concentrated effort to establish better testing and HPV vaccination programs in the highest-risk areas.

Cervical cancer can be beaten. Let’s work together to give Africa’s women the lives they deserve.

By Taofik Oloruko-Oba, Head of East Africa Network at Roche Diagnostic, Kenya.

References:

- 2022-Kenya-Facts-Figures.pdf (knbs.or.ke)

- https://hpvcentre.net/statistics/reports/KEN_FS.pdf

- https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cervical-cancer

- https://www.icrw.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/Technical-Brief-Unpaid-Care-2_uid_64be3e40b7b18.pdf

- https://www.statista.com/statistics/1233978/share-of-women-in-the-labor-force-in-kenya/

- https://www.nature.com/articles/s41591-023-02288-6

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC10433907/

- https://www.state.gov/partnership-to-end-aids-and-cervical-cancer/

- Kenya National Cancer Screening Guidelines -2018

We saved $57.9million from procurement of new verification devices, registration...

We saved $57.9million from procurement of new verification devices, registration...

Ejisu by-election: Aduomi is a betrayer – Ahiagbah

Ejisu by-election: Aduomi is a betrayer – Ahiagbah

Dumsor: I’ll be in police custody if I speak, I vex — DKB

Dumsor: I’ll be in police custody if I speak, I vex — DKB

We'll give daily evidence of Akufo-Addo's supervised thievery from our next gene...

We'll give daily evidence of Akufo-Addo's supervised thievery from our next gene...

Asiedu Nketia crying because they've shared the positions and left him and his p...

Asiedu Nketia crying because they've shared the positions and left him and his p...

Mahama's agenda in his next 4-year term will be 'loot and share' — Koku Anyidoho

Mahama's agenda in his next 4-year term will be 'loot and share' — Koku Anyidoho

If you're president and you can't take care of your wife then you're not worth y...

If you're president and you can't take care of your wife then you're not worth y...

Foreign Ministry caution Ghanaians against traveling to Northern Mali

Foreign Ministry caution Ghanaians against traveling to Northern Mali

GHS warns public against misuse of naphthalene balls, it causes newborn jaundice

GHS warns public against misuse of naphthalene balls, it causes newborn jaundice

Our education style contributes to unemployment - High Skies College President

Our education style contributes to unemployment - High Skies College President