Kranyanh Weefur, a Liberian Ambassador and progressive, departed this world on June 14, 2023. He was buried on July 8, 2023, in Mesurrado County, Liberia. He was 82 years old. Kranyanh was birthed in Monrovia on December 24, 1941, and was the son of Mr. Moses Kranyanh Weefur, Sr., Cecelia Weefur, and Mrs. Ida Ammah.

The ambassador graduated from the College of West Africa (CWA), a high school in Monrovia, Liberia, in 1966. He obtained a Bachelor's degree in political science and sociology from St. Peter College and a Master's degree in International Affairs from Columbia University in the US. After serving as Second Secretary and Vice Consul at the Liberian Embassy in Washington, DC, and as First Secretary at the Liberian Embassy in Rome, Italy, he became an Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary to the Republic of Cote d'Ivoire. He performed exceptionally well in these positions.

But while his education and positions were important, they did not mainly define his person. He was uniquely different. He stood for something. His cultural and social awareness and his progressive advocacy constituted his legacy. I will personally discuss them below.

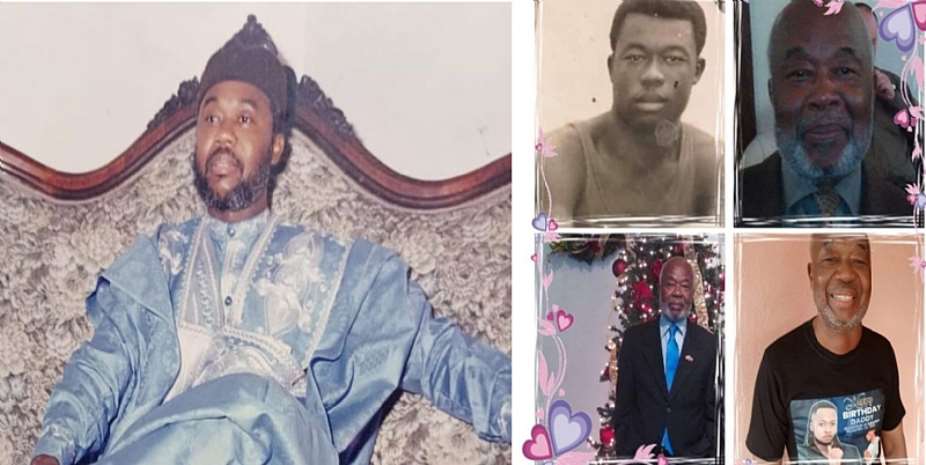

I met Kranyanh at CWA in the early 1960s (His high school picture on the right). We resided at the Methodist Boys Hostel, the school dormitory, with his three brothers, Richard, Clarence, and Moses, and other students, including Joseph Boakai, the late Willie Knuckle, and Eugene Peabody. I was surprised to hear him speak Kru, our traditional language. During those days, it was not fashionable to publically speak tribal languages or dialects, as some people called them. Most educated native parents who had obtained government positions did not encourage and motivate their children to speak traditional languages; for fear that the children would be considered "country children" if they spoke native dialects. And most native children, including me in the cities, wanted to speak English and become Americo-Liberians, the ruling class who descended from American Black ex-slaves who settled in the land now called Liberia in 1822. We admired their Western-oriented culture and, at the same time, were ashamed of ours.

Kranyanh was born speaking English. At about seven, he went to live in Grandcess, his father's village, which is now part of Grand Kru County. He became famous for his English-speaking ability. His peers adored him because of that, as Nyudueh Morkomana recalled. But while Kranyanh enjoyed this popularity, he realized that it isolated him from the general population that spoke Kru. He could not participate in general conversation. He felt terrible about this isolation. Within a few months, Kranyanh learned and spoke Kru fluently. He was happy to become part of his people and their culture.

At CWA, Kranyanh was one of my big brothers. They included Benjamin Dugba, Ralph Marshall, Lawrence Nya Taryar, and Eugene Peabody. As indicated in my autobiography, I looked up to them on campus, and they guided me.

When Kranyanh came to the US for further education, he became a founding member of Awina, thanks to Nyundueh. He told him of Krus in America, thinking about founding an organization called Awina, meaning in Kru, "Our Voice." Awina intended to advocate against Americo-Liberians' domination and for multi-party democracy in Liberia. The country had one political party then. Kranyanh was excited about the idea. Awina was organized in the early 1970s in New York. Its membership grew, entailing other Liberian natives in various American states.

On March 14, 1975, Awina staged a peaceful demonstration at the Liberian Embassy in Washington, DC. It was the first protest by Liberians in the Diasporas against the Liberian government. The regime in Liberia was stunned. It had not seen this before. At the march, we announced to the world Awina's manifesto:

"We organized to address the general issue of native suppression and repression in Liberia. We believed that only through a radical approach would the regime in Liberia take us seriously and improve the condition of all Liberians. Moreover, AWINA is dedicated to liberating Liberia from Black Colonialism as a revolutionary organization. We view the struggle as the people's struggle because the people and only the people alone are the motives in making history."

Teniweti Toh, Kranyanh, Nyundueh, and others headed the demonstration. Teniweti led Awina as national leader. Comrade Siahyonkron Nyanseao and I functioned as editors of the Awina Drum, the organization's newspaper.

Kranyanh was also active in the Union of Liberian Associations in the Americas (ULAA), representing the New York-New Jersey association. Several years after the protest, in 1979, ULAA held a mass demonstration in Washington, DC, and in New York against the Tolbert government. The advocacy responded to the administration's killing of unarmed Liberians in the rice riot. Kranyanh was part of the demonstrations.

Kranyanh's self-awareness can also be attributed to his father, Moses Kranyanh Weefur. The father served as a principal of the Booker T. Washington Institute (BWI) in Liberia during William Tubman's presidency. Under the administration of William Tolbert, he headed the JFK Hospital. He later served as a representative of Margibe County in the Liberian House of Representatives. Mr. Weefur told me he met hardship as a boy in Grandcess. He became a ward living with influential ruling-class people to acquire an education. He lived with a man called Diggs in Grand Bassa County. Diggs named him Moses Diggs. Later he resided with Clarence Simpson, former Vice President under Tubman. Mr. Simpson named him Moses Simpson, but the father politely resisted. He returned to his family name, Weefur or Weefluh, meaning Big Road in Kru. In appreciation of Simpson's help, he named his second son Clarence in Simpson's honor. "I was tired of taking other people's names. I was losing my identity, and I was unhappy", he said.

In addition to his self-awareness and progressive advocacy, Ambassador Weefur was honest, cheerful, and likable. He loved dressing and liked fine clothing. He controlled his emotions and did not display undue anger toward others. Moreover, he was not pompous. He was modest. Before he worked in the Liberian Foreign Service, he returned home. Without a job, he became a taxi driver in Monrovia. When he came back to the US and told me, I asked.

"Did you ready do that?"

He answered, "Yes I did, and I was not ashamed for I was earning honestly. I did not beg, nor requested help from family members."

I admired his independence and personality. Upon his appointment to the Liberian Embassy in Washington, DC, he and his wife Hawa stayed with me briefly until they found their place in Silver Spring, Maryland. Again I noticed his love for clothing, displaying his refined style. His favorite dish was palm butter. He liked it "souppee souppee", as he described it.

Kranyanh was first married to Hawa Beyslow, a Liberian. He later married Zeineh Ahmed, an Ethiopian. Lastly, he wedded Christina Akel, a Liberian. His wife, Christina, his children, Wortaji, Semah, Laila, Tecumpla, Linda, Kranyanh, and many siblings survived him.

Before his death, I visited him in Monrovia. He had returned from the Foreign Service and was not too well. I had not seen him for about 20 years since our meeting in the US. He greeted me, saying in Kru, "Na fluh da," meaning how your body is?

"Na fluh noon shun," meaning my body is well. I replied.

Then I asked, "Kind na fluh da?" How is your body too?

He replied. "Na fluh ne Neswa kleh," saying my body is with God.

He told me about his health: he suffered from high blood pressure and diabetes. We talked about the old good days at CWA and in America. He asked about old US friends; some, unfortunately, had died. We talked and laughed. Before, he introduced his family to me. I was happy to meet them. His youngest child, Linda, about 4 years old, played with him, touching his beard as we spoke. His son, Semah, was sitting next to me. Semah was born blind, Kranyanh told me.

"I am sorry about that," I said. But Semah was friendly.

"Uncle Nyanfore, I am happy to meet you. Daddy has talked about you a lot", Semah said.

I was moved by Semah's spirit. He was genuine.

I spoke about Favour (Chinedu Okoli), the famous Nigerian musician, his excellent work, and his collaboration with a blind Liberian boy. Then Kranyanh laughed and said, "The boy is Semah sitting next to you."

I was pleasantly shocked.

"You mean your son, Semah?" I asked.

"Yes," he replied.

"My God, this is wonderful. I am in the present of a celebrity whose music is international". I said happily.

Semah was smiling. "Do you want me to sing for you, Uncle Nyanfore?"

"No thanks Semah, your talent followed you. I am happy for you. God will continually bless and be with you", I said.

Then Kranyanh and I talked about other things. Semah had left. I asked Kranyanh the reasons for his recall from the diplomatic service by President Ellen Johnson Sirleaf. He told me he did not really know. I asked if he tried to know.

"I did but could not be informed of the reasons." He answered.

"Did you ask your CWA classmate former Vice President Boakai to find out?" I followed.

He laughed. "I did but Boakai said he could not interfere. Boakai was correct. The president has the constitutional right to appoint and dismiss at will." He said, smiling.

Here he showed his maturity and emotional control. I said to myself. "This guy has a good personality. He speaks without anger and malice".

Interestingly, Sirleaf called his mother Cecelia, aunty when the mother was alive. Also, Sirleaf's late husband, Doc Sirleaf, worked with Kranyanh's father at BWI. Kranyanh and Benedict Rick, whom the Sirleafs raise, was Kranyanh's best friend. In other words, Sirleaf knew Kranyanh very well. But why could she tell him the reasons for her action? I asked myself.

Kranyanh displayed a similar attitude in a situation with the late Ernest Eastman, then Foreign Minister under President Samuel Doe. According to Kranyanh, he gave his CV to Eastman for presentation to the president for consideration for appointment in the Foreign Service. Eastman sat on the CV and failed to discuss it with Doe, giving Kranyanh the run-around. Fortunately, Kranyanh met Doe's armed forces chief, Henry Dubar, who took a copy of the CV to the president resulting in Kranyanh's appointment to Washington, DC. When Eastman found out, he got angry with Kranyanh, saying Kranyanh passed over him to talk to Doe. Eastman made life difficult for Kranyanh in DC. But Kranyanh did not react negatively toward Eastman. He was calm. Eastman observed Kranyanh's composed and peaceful behavior and finally befriended Kranyanh. "We became good friends after," Kranyanh recalled.

On his dying bed at the hospital, his wife Christina said he asked to see his family. Christina brought the children. They prayed for him and cried. He consoled them. Later he died with a smile on his face. When Christina told me what happened, I said, "He wanted to say goodbye, and was happy to be with his ancestors."

The church was parked during his funeral. Family, friends, organizations, the Liberian government, and Favour paid tributes to him. I, too, did as a family member. A former ambassador praised him as an honest man.

He was an inspiration. We will remember him not for his education and political appointments but for what he stood for; his honesty, integrity, personality, cultural pride, and advocacy for social justice.

I pray that his soul rests in perfect peace!

Azumah Nelson faces Irchad Razaaly in a match to empower youth

Azumah Nelson faces Irchad Razaaly in a match to empower youth

Ejisu By-Election: I’m not a traitor, NDC people appreciate me – Independent can...

Ejisu By-Election: I’m not a traitor, NDC people appreciate me – Independent can...

Some people expect us to be dogmatic, sycophantic supporters of Akufo-Addo even ...

Some people expect us to be dogmatic, sycophantic supporters of Akufo-Addo even ...

NDC Campaign: James Agyenim Boateng is the right man to handle communications

NDC Campaign: James Agyenim Boateng is the right man to handle communications

Mahama pledges to contribute to the development of Gonja Kindom

Mahama pledges to contribute to the development of Gonja Kindom

“Ghanaman Time”: We've normalized the abnormal, accepted the unacceptable — Dots...

“Ghanaman Time”: We've normalized the abnormal, accepted the unacceptable — Dots...

Bawumia begins nationwide campaign, starts in Eastern Region today

Bawumia begins nationwide campaign, starts in Eastern Region today

Bawumia kicks off nationwide campaign with “bold solutions” for Ghana's future

Bawumia kicks off nationwide campaign with “bold solutions” for Ghana's future

You cannot choose your successor; it’s only God who can – Mahama to Akufo-Addo

You cannot choose your successor; it’s only God who can – Mahama to Akufo-Addo

Ejisu by-election: Vote for independent candidate Kwabena Owusu Aduomi to uphold...

Ejisu by-election: Vote for independent candidate Kwabena Owusu Aduomi to uphold...