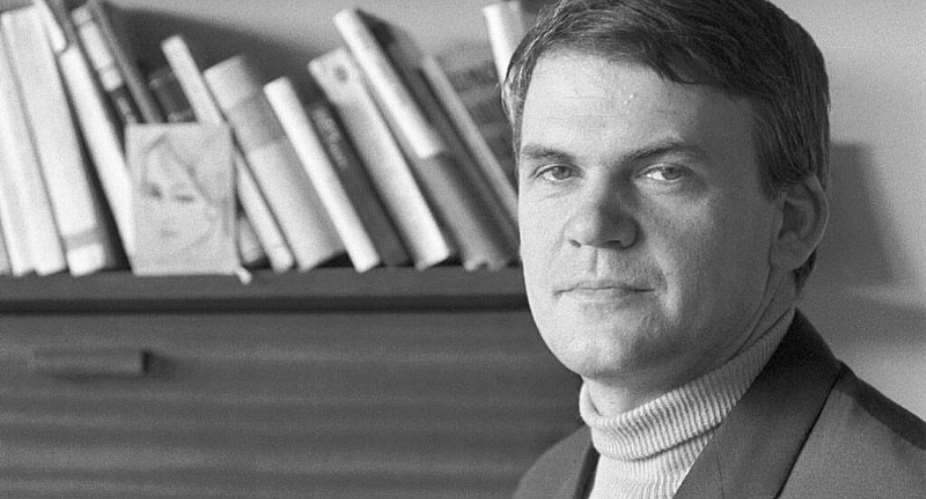

Czech-born writer Milan Kundera, who has died in Paris at the age of 94, lived almost half his life in France. A self-described Francophile, he wrote his later works in French and was convinced that being exile enriched his writing.

"The spiritual atmosphere of my entire Czech youth was marked by passionate Francophilia," Kundera wrote in 1994.

In an essay for French literary magazine the Revue des deux Mondes ("Review of the Two Worlds"), the author positions France as the seat of European culture.

Among his generation of Czech intellectuals, he writes, admiration for the country persisted in spite of the politics that saw France, along with the United Kingdom and Italy, agree to Nazi Germany's annexation of a swathe of what was then Czechoslovakia in 1938.

"How did it survive? Because the love of France was never located in admiration for French statesmen, never in identification with French politics; it was exclusively in passion for French culture: for its thought, its literature, its art."

Embraced by France

This passion was evident in Kundera's earliest work, which included translations of poems by French poet Guillaume Apollinaire. References to other French writers are scattered throughout his novels.

The admiration was mutual. In the 1960s, when intellectuals in both countries were drawn to certain elements of communism while being alienated by the parties that were supposed to embody them, Kundera's debut novel "The Joke" – the tale of a young man expelled from the party for a sarcastic remark to a girlfriend – was embraced by French readers.

Poet Louis Aragon wrote the foreword to the French edition, in which he called it "one of the greatest novels of the century".

He also introduced Kundera to the renowned French publisher Charles Gallimard, who would eventually convince the writer to emigrate to France when he was expelled from the Communist party himself in the aftermath of the Prague Spring. Gallimard and his contacts helped secure a teaching position for Kundera at the University of Rennes in Brittany, starting in 1975.

"I'm a Francophile, an avid Francophile. But the reason I'm here is really because the French wanted me. I came to France because I was invited, because people here took the initiative and arranged everything," Kundera told the New York Times in 1984. "And I was lucky because I do feel good here – much better than I feel in, say, Germany."

By then, Kundera and his wife Vera had been in France for nine years. When they first left Prague for Rennes in the summer of '75, carrying visas that granted them the right to stay in France for "730 days", as Vera Kundera would later recall to French newspaper Le Monde, her husband was convinced he would return.

"Life as a permanent migrant would depress me," he told a German magazine a few months later.

But by 1984, he had taken French nationality, the Kunderas were settled in Paris and Milan had just published what would become his best-known novel, "The Unbearable Lightness of Being". Written in Czech and set in Prague, the novel appeared first translated into French, then in English.

In an interview with French television the same year, Kundera said that his life in exile had served to enrich his work as a novelist.

"There's a certain cliché that everyone repeats of a man like me practically chased out of his country. It's a situation that we think of as tragic, and it is tragic. But luckily all human situations are paradoxical – it's always the paradox that saves us," he told the literary talk show Apostrophes.

"The paradox in my case is that I lost my first country, and that I'm very, very happy in France."

'I chose France'

Kundera would go on to transition into writing in French, the original language of most of his work from the mid-1990s onwards. Critics were divided over the choice, with some reviewers hailing it as self-reinvention and others finding the results lacklustre.

But as Kundera saw it, he faced a choice: "Do I live like an emigré in France or like an ordinary person who happens to write books? Do I consider my life in France as a replacement, a substitute life, and not a real life? ... Or do I accept my life in France – here where I really am – as my real life and try to live it fully?"

He told the New York Times: "I chose France – which means that I live among Frenchmen, make French friends, talk to other French writers and intellectuals. There is such a rich intellectual life here, and for us that means a circle of friends who are themselves a kind of protection against these questions. It means that whether or not I'm actually 'at home' in France, I have nice amiable friends with whom I am at home."

In the same interview, he observed that French lacks a single word for "home", and wondered "if our notion of home isn't, in the end, an illusion, a myth".

Kundera may have been able to let go of the idea of home, but he refused to give up his idea of France. He continued to live here long after the fall of communism and the government that stripped him of Czech nationality in 1979. (It was eventually restored in 2019.)

Even as the rest of Europe and France itself changed, Kundera remained attached to the values that it stood for in his mind. As he wrote in his 1994 essay, the fact that others seemed to regard them less only gave him "another reason for me to love France; without euphoria; with a love that is anguished, stubborn, nostalgic".

2024 elections: Campaigning for 'incompetent' Mahama an insult to Ghanaians — Fo...

2024 elections: Campaigning for 'incompetent' Mahama an insult to Ghanaians — Fo...

Bawumia promises release of monies owed nursing trainees

Bawumia promises release of monies owed nursing trainees

2024 elections: We'll not tolerate NPP's intimidation, 'killing' tactics — Musta...

2024 elections: We'll not tolerate NPP's intimidation, 'killing' tactics — Musta...

ECG workers rubbish Bawumia's 'ransomware attack' claim

ECG workers rubbish Bawumia's 'ransomware attack' claim

Mahama created unemployment when he was president; we have created jobs for Ghan...

Mahama created unemployment when he was president; we have created jobs for Ghan...

"Help my tenure to be a memorable one" — Finance Minister tells GRA staff at Afl...

"Help my tenure to be a memorable one" — Finance Minister tells GRA staff at Afl...

Bawumia has selected running mate already – Sammi Awuku reveals

Bawumia has selected running mate already – Sammi Awuku reveals

Dismiss Addai-Mensah as KATH CEO – Group petition Akufo-Addo

Dismiss Addai-Mensah as KATH CEO – Group petition Akufo-Addo

VRA Senior staff association kick against privatisation calls

VRA Senior staff association kick against privatisation calls

Prices of goods to increase as traders can’t restock, repay bank loans due to ce...

Prices of goods to increase as traders can’t restock, repay bank loans due to ce...