Every country is battling with corruption in one form or another. This does not spare those countries often heard lecturing others on the subject. Corruption, if it be known, is not a straightforward term never mind figuring out 'who the cap fits'. Whilst its notions of immorality, thievery and all manner of wrongs seem in hand, its political usage is incredibly problematic.

As a result, the war against corruption often ends up as one of words instead of clear-cut action. The dilemma for Ghana is how to ensure that whatever is proposed as a solution is founded on descriptors that are clear to the whole nation.

One of the key indicators in the fight against corruption is the sense of how the citizenry generally view their country. Ghana, for this matter, cannot be seen as being 'out-of-touch'. Providing that its citizenry can abstract what is theirs as a stake, well-meaning Ghanaians will jump onboard.

The country must, at all times, visibly demonstrate that it is gaining grounds on combating corruption even if working structures are still in their infancy. However, this logic is often lost in the 'over-politicisation' of allegations which in turn adds more confusion and very little by way of a lasting solution.

To avoid the frustration of governments coming and going with little or no progress, Ghana has to deliberate what is viable as an approach. So far, differentiating the citizenry into the people and politicians in its notion of an 'us and them' situation has not delivered the goods.

In the 'mix up', few attempts are made to expound corruption as a function of power. As such, the inter-dependable relationship that is critical to its resolution is defunct of the attitudes, values and integrity to make an impact. In this vicious circle, things usually end up back at square one.

Irrespective of who is in charge, an incorruptible state must be courageous in its exaction of leadership. This means doing the right thing at all costs. Furthermore, the process has to be 'shored up' by guidance and directives as clarification of the powers and rights available to the citizenry.

Moreover, anti-corruption measures have to be 'watertight' in their modus of accountability, probity and transparency right through to their enforcement. This said, the whole process requires a culture of openness in which people will not be scared to 'call a spade a spade'.

Reverence of the state is perhaps the only real antidote to fighting corruption. This is where statutes such as the constitution, legislative framework and so on come into play. In this sense, the state's authority is not only paramount but also resolute in its articulation of the collective will.

But without blaming any particular camp, aspects of Ghanaian politics have not always measured up to this benchmark. Until the intervention of the Supreme Court Judges, Ghana was reeling under the vices 'political tin gods' who felt that there was one rule for them and another for the rest.

Good governance, in the fight against corruption, means achieving national aspirations through people. As such, the satirical view of Ghanaians 'haggling' as if they have a price tag on their forehead does not help. At the same time as distorting the collective will, it sets back good governance.

Moreover, it sends the wrong signals to those at the helm of the state, politicians and public servants alike regarding the authority at their disposal. Despite being paid handsomely, the miscreants amongst them will let greed get in the way of their consciences in a cue to 'chop and loot' as if there is no tomorrow.

Without being pedantic, corruption is founded on negative power. Accordingly, it downgrades the ethical and moral duty on the citizenry to police and safeguard Ghana's interests. At worst, sections of the population adopt a 'galamsey' attitude towards everything about the state not just its mineral resources.

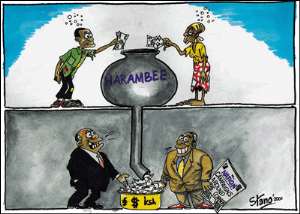

Overall, it paints a disturbing picture of a Ghana where 'few live-it-big' whilst the rest including those who want to do right thing and have the potential to transform the country are marginalised. If this is what some prize as democracy, corruption is not budging yet,

Africa, politically, for decades has been a caricature of 'political opportunism' fuelled by greed and individual wealth accumulation at the expense of ordinary Africans. Much of this aligns itself with a 'colonial legacy' to frustrate the continent's development.

Sadly, many Africans, not just Ghanaians, refuse to see the 'train-of-thought' of what they can do for their country rather than the other way around. Despite all the noises on democracy, if Africa cannot put right this fundamental problem, it will continue to be plagued by corruption even with leaders of good intent and integrity.

The dilemma facing Ghana's anti-corruption crusade can be summarised by way of two important questions. Why do people continue to throw huge sums of money at politics despite other ways of cementing a lasting legacy? Likewise, why do Ghanaians buy into this modality of existence?

Understanding how both layers marry into instruments of corruption will help to overcome the dilemma. Be it a war of words or action, Ghana has to be clear about the context that it will rely on to fight this scourge in order to make good of its resources capabilities.

We saved $57.9million from procurement of new verification devices, registration...

We saved $57.9million from procurement of new verification devices, registration...

Ejisu by-election: Aduomi is a betrayer – Ahiagbah

Ejisu by-election: Aduomi is a betrayer – Ahiagbah

Dumsor: I’ll be in police custody if I speak, I vex — DKB

Dumsor: I’ll be in police custody if I speak, I vex — DKB

We'll give daily evidence of Akufo-Addo's supervised thievery from our next gene...

We'll give daily evidence of Akufo-Addo's supervised thievery from our next gene...

Asiedu Nketia crying because they've shared the positions and left him and his p...

Asiedu Nketia crying because they've shared the positions and left him and his p...

Mahama's agenda in his next 4-year term will be 'loot and share' — Koku Anyidoho

Mahama's agenda in his next 4-year term will be 'loot and share' — Koku Anyidoho

If you're president and you can't take care of your wife then you're not worth y...

If you're president and you can't take care of your wife then you're not worth y...

Foreign Ministry caution Ghanaians against traveling to Northern Mali

Foreign Ministry caution Ghanaians against traveling to Northern Mali

GHS warns public against misuse of naphthalene balls, it causes newborn jaundice

GHS warns public against misuse of naphthalene balls, it causes newborn jaundice

Our education style contributes to unemployment - High Skies College President

Our education style contributes to unemployment - High Skies College President