About 80km east of Pretoria in South Africa, near the town of Bronkhorstspruit, there's a rocky outcrop in a secluded ravine in the countryside. There's nothing remarkable about this outcrop – which has, over the years, made it a good place to shelter or hide. But the rock shelter's back wall contains a remarkable piece of South African history.

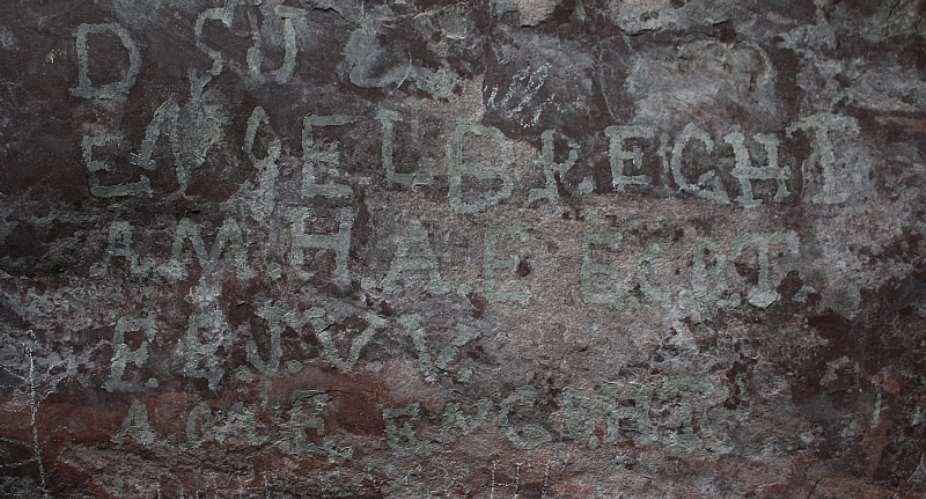

There you can see images of women in crinoline dresses, as well as names and initials, painted onto the rock. The surname 'Engelbrecht' is repeated in several places with the initials 'A.M.H.A.E.' as well as 'D.S.J.' and 'A.M.E.'. Other names and initials include 'J.D. van Schalkwyk' and 'E(F?).B.J.V.V.'.

This “graffiti” was made by Boer women hiding from British soldiers during the South African War, also known as the Boer War. “Boer” is an Afrikaans word which translates to “farmers” but also refers to the forebears of South Africa's Afrikaans people. These women left their farm homes and lived outdoors in the countryside to avoid being captured by British forces and sent to a concentration camp .

My colleagues and I wanted to know more about the site's occupants, their lives while in hiding, and the “graffiti” they left behind. So we analysed these painted images, as well as others left there earlier by different groups like indigenous hunter-gatherers, herders and farmers. This helped us to understand the site's painted sequence and the context of its occupation over time. An examination of family stories helped fill in the gaps in the women's stories.

Stories like the kind stored in this place, known as Telperion Shelter, provide history to a landscape and people. Women were important participants in the war through the contributions and support they provided to commandos, units of Boer fighters. This is seldom spoken of; their stories and experiences are neglected. Telperion confronts these hidden stories.

The South African War

The South African War was declared between the British and Boers in 1899 after a period of economic and political instability.

The scattered Boer troops engaged in guerrilla tactics, crippling British resources, terrorising battalions and cutting off supply lines.

Two of the strategies the British used had devastating effects on the Boers' home life. One involved burning down farmsteads and destroying crops and livestock. The other was to intern the Boers in concentration camps.

Women left without homes would often be forced to subsist in the veld – the open, uncultivated grasslands. It was a dangerous option: they faced capture, retribution, food insecurity, disease and death. But it meant avoiding the concentratin camps, which were overcrowded, undersupplied and poorly maintained, with a constant threat of disease. Nearly 50,000 people died in the camps.

While in the veld, women were also able to give their husbands in the commandos supplies and information about soldier movements. This was often vital to a commando's ability to continue fighting. Going to the veld, in this sense, was about resilience, rebellion and defiance. Unfortunately, because most of these stories, histories or experiences were never written down or recorded, they are poorly known.

Stories on the stone

When we first visited Telperion Shelter, the farm manager told us a story about those who had lived there. Black, Sotho-speaking families and white Boer families hid there from patrolling British troops. They set up a small garden inside a poplar tree thicket nearby and even kept a pig.

One day the pig escaped and nearby troops happened upon it; this led them to discover the families. All were captured and sent to a concentration camp.

Nothing more is known. But we felt that the paintings inside the shelter might tell us more about the site's occupants and their experiences.

The “graffiti” includes the names I've mentioned as well as images of two groups of people. One group is five women wearing large crinoline dresses, which would have been worn at the time of this war, and holding what look to be stalks, which could be maize or something yet to be identified. The second group is to the right and almost identically resembles Sotho images of people, painted by earlier Sotho communities using the site for boys' initiation. It is drawn in the same paint as the women. These two groups might reflect the two occupant communities using the shelter.

Our most important task was to find out who used the site and what happened to them; if we could do so we would be able to assess whether the story we were told was accurate and perhaps add to it. Fortunately, all of the concentration camp records have been digitised and are available online .

Poring through these records, we were eventually able to identify Alida Maria Hendrika Aletta Engelbrecht (A.M.H.A.E) and her husband and children, some of whom also have their names painted in the site. According to the records, she and her children were all captured on the farm Sterkfontein, where Telperion Shelter is found. It appears as though we have found the people in the story and who used the site.

These images do more than just verify the story we were told. They add layering to it. And they commemorate the experiences that many women and children underwent and the difficulties of living in the veld. Ultimately, they are a different form of story telling.

Tim Forssman receives funding from the Palaeontological Scientific Trust and the National Research Foundation.

By Tim Forssman, Senior lecturer, University of Pretoria

Elisu By-election: "If you call yourself a man, boo Chairman Wontumi again" — Bo...

Elisu By-election: "If you call yourself a man, boo Chairman Wontumi again" — Bo...

Fuel tanker driver escapes with his life after tanker goes up in flames near Suh...

Fuel tanker driver escapes with his life after tanker goes up in flames near Suh...

Uniform change: ‘Blue and white are brighter colours’ — Kwasi Kwarteng explains ...

Uniform change: ‘Blue and white are brighter colours’ — Kwasi Kwarteng explains ...

MoE not changing all public basic school uniforms but only newly built ones — Kw...

MoE not changing all public basic school uniforms but only newly built ones — Kw...

We’re only painting new public basic schools blue and white – Dr. Adutwum clarif...

We’re only painting new public basic schools blue and white – Dr. Adutwum clarif...

Bawumia has lost confidence in his own govt’s economic credentials – Beatrice An...

Bawumia has lost confidence in his own govt’s economic credentials – Beatrice An...

I fought WW2 at age 16 – WO1 Hammond shares At Memoir Launch

I fought WW2 at age 16 – WO1 Hammond shares At Memoir Launch

GRA-SML deal: Regardless of what benefits have been accrued, the contract was aw...

GRA-SML deal: Regardless of what benefits have been accrued, the contract was aw...

April 26: Cedi sells at GHS13.75 to $1, GHS13.18 on BoG interbank

April 26: Cedi sells at GHS13.75 to $1, GHS13.18 on BoG interbank

Champion, promote the interest of women if you become Vice President – Prof. Gya...

Champion, promote the interest of women if you become Vice President – Prof. Gya...