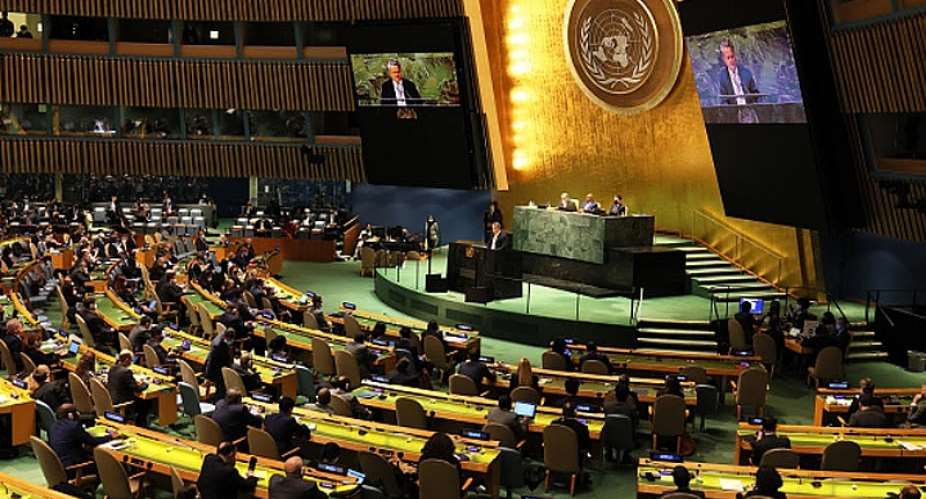

In recent weeks, the world has witnessed the most tense situations in international relations since the end of the Cold War with Russia's invasion of Ukraine. These tensions were noticeable during the deliberations and during the vote of the members of the United Nations on the resolutions calling on Russia to end its invasion and withdraw its forces from Ukraine. These events also served to test the resilience of military and political alliances.

The 54 African countries, (or 27.97% of the total vote) considerably influenced the vote.

First, a meeting with the 12 members of the Security Council was held on February 25, 2021. The three countries representing Africa, namely: Gabon, Ghana and Kenya, along with eight other countries have voted for the resolution. However, Russia used its veto power to block it. This veto prompted the United States and 94 countries to call an emergency meeting of the United Nations General Assembly on February 27, 2022, at which a similar, but non-binding, motion was introduced. This is the first emergency meeting of this Assembly in 40 years.

The resolution providing, among other things, for the condemnation of the Russian decision “to raise the level of alert of its nuclear forces was adopted by the two-thirds majority required by all the Member States.

The African votes were less unanimous in the General Assembly than in the Security Council where the allocation of non-permanent seats, even if they obey a certain geographical distribution, does not oblige the representative countries to be the bearers. words from their region.

The majority of African countries clearly sided with Ukraine – 28 out of 54 (or 51.85%). Only Eritrea voted against this resolution. But almost a third of them abstained from taking sides (or 17 out of 54) – assuming that abstention is halfway between yes and no. Eight countries were absent.

My research focused on the similarities and differences in how countries respond to crises. As an example, I looked at the 2015 refugee crisis in Europe and the contradictory reactions of Western and Eastern European countries, which I explained by their different identities, i.e. by "Who are we? ".

I also reviewed the Valletta Joint Action Plan, an immigration pact signed by the European Union and the African Union in response to the refugee crisis. I demonstrated that the plan, which helped to relaunch relations between the AU and the EU, was based on the interdependence which allows the parties to preserve their interests (territorial integrity for Europeans and economic development for Africans), while acknowledging (especially the more powerful Europeans) that they need each other to advance these interests.

Research by authors such as the Dutch political scientist Erik Voeten further proves that voting in the General Assembly is – in general – driven by interests. But, as American political scientist Alexander Wendt has revealed, what constitutes an interest depends on the perception of each government, so much so that two rival countries can sometimes vote for the same resolution.

As Voeten pointed out, historically speaking, electoral trends have been influenced by the big issues of the moment. In the 1950s, colonialism pitted European countries against Asian and African countries; from the 1960s to the 1980s, it was the Cold War and the division between the Eastern and Western blocs. More recently, these electoral tendencies have been structured by the desire of developing countries to obtain or retain aid from developed countries and, increasingly, between the liberal, illiberal divide of democratic and authoritarian regimes.

This divide trumps other possible explanations for the electoral trends of the General Assembly's emergency meeting on the invasion of Ukraine. A country's degree of proximity to the West or Russia can also serve as an additional explanation.

The line of demarcation

The group of 28 African countries in favor of the resolution was mainly made up of Western-aligned democracies such as: Benin, Botswana, Cape Verde, Comoros, Democratic Republic of Congo, Gambia, Ghana, Kenya, Lesotho, Liberia, Malawi, Mauritius, Niger, Nigeria, Sao Tome and Principe, Seychelles, Sierra Leone, Tunisia and Zambia.

But a few undemocratic or hybrid regimes made the list, such as Côte d'Ivoire, Gabon, Libya, Chad, Egypt, Mauritania, Rwanda and Somalia. They had, however, one thing in common: being allies of the West, with close military ties (military bases and joint military operations against the jihadists).

Conversely, most of the 17 African countries which abstained or which, like Eritrea, voted against the resolution, are authoritarian or hybrid regimes; these include, among others, Algeria, Angola, Burundi, Central African Republic, Congo, Equatorial Guinea, Madagascar, Mali, Mozambique, South Sudan, Sudan , Tanzania and Zimbabwe.

Some of these countries have close military and ideological ties with Russia, sometimes dating back to the Cold War, such as Algeria, Angola, Congo, Mozambique, Zimbabwe, Mali and the Central African Republic.

A few exceptions to the rule were also noteworthy.

A number of functioning democracies – Namibia, South Africa and Senegal – also abstained. All have strong affinities with the West. However, in the case of Namibia and South Africa, their ruling parties (the People's Organization of South West Africa respectively) received support from the Soviet Union during their struggles for independence.

The case of Senegal is more puzzling, this country being the darling of the West due to its long democratic tradition. The Senegalese government said its abstention was in line with "principles of non-alignment and peaceful settlement of disputes". However, the official statement of its President, as current President of the African Union, like that of the President of the AU Commission, could be interpreted as support for the territorial integrity of Ukraine.

This liberal and illiberal divide conveys points of view of three kinds.

First, the world is being turned upside down by the kind of clash of civilizations predicted by American political scientist Samuel P. Huntington, who claimed that cultural identity would be the fault line in global conflict. This would prepare the ground for world civilizations: Western, Chinese, Islamic, Latin, Slavic and perhaps African. If the idea that he had of a confrontation – and of identity as a driving force – seems to materialize, this identity is based on ideology and not on culture, illiberalism having replaced communism.

Simply, we had not yet reached the stage of the triumph of democracy proclaimed by the American political scientist Francis Fukuyama, in his book entitled The End of History, published in 1992 after the fall of the Berlin Wall.

Second, authoritarian regimes find comfort and support for their survival in proximity to similar regimes, and it serves as their insurance policy. Since Russia has shown its determination to rescue authoritarian regimes, such as Syria, these countries do not want to rule out the possibility of resorting to its assistance, in the event of a threat to their survival.

Third, if the war in Ukraine escalates globally and a China-encompassing Cold War 2.0 takes hold, African countries would split into several blocs instead of presenting a common front.

Placed in the context of the renewed partnership between the EU and the AU, this divide makes even more sense now than at their summit in Brussels, a week before the outbreak of the conflict, during which they proclaimed a common vision for 2030 and sought to form a strategic alliance.

In terms of democracy and alignment, the EU could probably make more demands and will naturally seek to deepen its relations with like-minded African countries.

Mahama Tawat does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

By Mahama Tawat, Research fellow, Université de Montpellier

There’s enough time to make significant contributions - Akufo-Addo tells new Min...

There’s enough time to make significant contributions - Akufo-Addo tells new Min...

Akufo-Addo calls on media to uphold integrity, ethics

Akufo-Addo calls on media to uphold integrity, ethics

NPP has run out of ideas on how to resolve issues facing Ghanaians — Mahama

NPP has run out of ideas on how to resolve issues facing Ghanaians — Mahama

NDC has the people to turn Ghana’s fortunes around and put us back on track — Ma...

NDC has the people to turn Ghana’s fortunes around and put us back on track — Ma...

SSNIT hotel divestiture: ‘There’s no breach in Rock City’s deal’ — Bryan Acheamp...

SSNIT hotel divestiture: ‘There’s no breach in Rock City’s deal’ — Bryan Acheamp...

You were appointed to provide public service not to appropriate personal gain — ...

You were appointed to provide public service not to appropriate personal gain — ...

Ghanaians are experiencing too much pain — Archbishop Duncan-Williams laments

Ghanaians are experiencing too much pain — Archbishop Duncan-Williams laments

I'll work hard to ensure Ashanti region reaches its full potential if voted pres...

I'll work hard to ensure Ashanti region reaches its full potential if voted pres...

SSNIT hotel divestiture: Scale down real estate business to end politician inter...

SSNIT hotel divestiture: Scale down real estate business to end politician inter...

May 21: Cedi sells at GHS14.79 to $1, GHS13.84 on BoG interbank

May 21: Cedi sells at GHS14.79 to $1, GHS13.84 on BoG interbank