Introduction

The passage of the Mental Health Act in 2012 was an important milestone for Ghana’s mental health system, considering the system’s “lunatic” history. In the ensuing paragraphs, this article offers a brief narrative about the history of mental health in Ghana, highlights certain important legislative issues which needs to be addressed and discusses why the implementation of the Mental Health Act will be an additional burden to an overwhelmed mental health system.

History of Mental Health in Ghana

Attempts to regulate mental health in Ghana date back to the latter part of the 19th Century. In 1888, the Lunatic Asylum Ordinance (LAO) was enacted under the governorship of Sir Griffith Edwards. This ordinance was rather draconian, as it labelled the mentally ill “insane” and ensured their arrest and imprisonment. Such was the zeal and fervour to carry out the provisions of the Ordinance that by the close of the century, the special prison in which the mentally ill were reposed, had become congested. This called for the construction of a “lunatic asylum” in 1906. This asylum is the present Accra Psychiatric Hospital.

In 1951, the Accra Psychiatric Hospital had its first Psychiatrist in the person of Dr. E.F.B Foster, a native of Gambia. He continued reforms undertaken by his predecessors Dr Maclagan (1929-1946) and Dr. Wozniak (1947-1950) and furthered steps to eradicate the prevailing injustice and make the facility more humane. He transformed the “lunatic asylum” into a hospital. Indeed, this semantic transformation was an imperative response to the equity and justice question: if mental illness is just like any other illness, then why should the mentally ill be treated differently from the others? Under the leadership of Dr. Foster, more Doctors and Nurses were trained in addition to other initiatives to improve the hospital. The Accra Psychiatric Hospital was the only established Psychiatric facility in West Africa in the early 50s. Two additional psychiatric hospitals were built in 1950 and 1970 respectively.

After Ghana’s independence in 1957, part of a comprehensive plan for the health sector was the construction of five new mental health hospitals supported by Psychiatric units to accommodate about 1,000 people. At the time, Ghana’s population was below eight million.

The ordinance still remained enforceable until the enactment of the Mental Health Act 1972 (NRCD 30), which focused on institutional care taking into account the patient, the property of the patient and voluntary treatment.In 1983, under the Provisional National Defense Council’s (PNDC) regime, improvement of psychiatric services especially at the Accra Psychiatric Hospital became a concern. A committee which was formed in this regard, saw the need to integrate mental health within the larger health sector. Their recommendation led to the creation of a Mental Health Unit within the Ministry of Health.

Currently, there are only three Public Psychiatric Hospitals (Accra, Pantang and Ankaful) in the country, all located in the Southern part of the country with 1200 beds altogether. There are about six privately operated ones. From 1957 to date, 59 years and counting, the strategic vision for five new mental health hospitals is yet to be realised.

Mental Health Legislation: Inconsistencies and Illogicalities

In 2004, the mental health bill (now an Act) was introduced in Parliament. The bill took into account modern trends, standards and best practices and also made provisions for the regulation of public and private mental health facilities in the country. The bill spent eight (8) years on the shelves of Parliament before being passed into law. Below are some legislative issues before and after the passage of the bill into law:

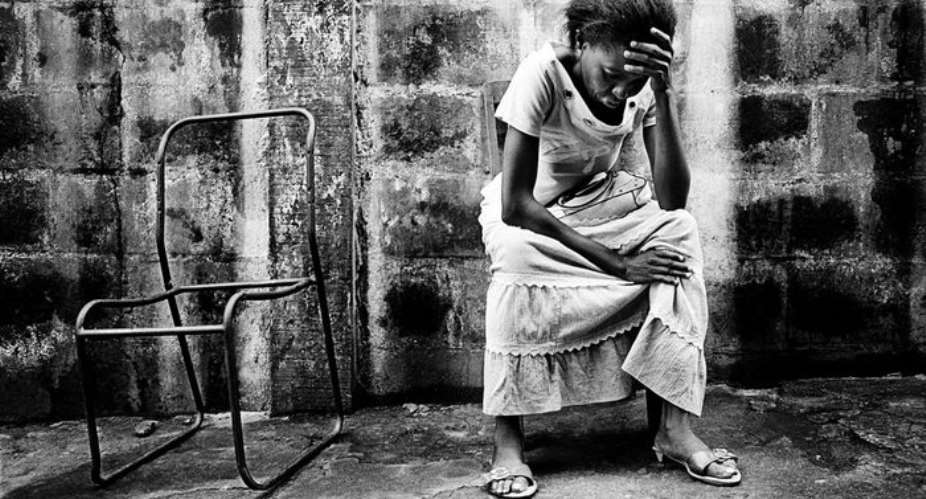

- Though the 1992 Constitution of Ghana, article 15, paragraph 2 states that “no person shall...be subjected to (a) torture or other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment, (b) any other condition that detracts or is likely to detract from his dignity and worth as a human being,” we have not yet included the offense of torture, as defined in article 1 of the Convention against Torture and other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, in our Criminal Code, 1960 (Act 29). Denial of adequate food, shackling to trees or metal objects and arbitrary flogging are some of the cruel, daily experiences of some mentally ill persons. These practices are tantamount to torture.

Human Rights Watch, in its 2012 report, “Like a Death: Abuses against Persons with Mental Disabilities in Ghana” found that persons with mental disabilities in Ghana often experience a range of human rights abuses in some prayer camps and hospitals. These patients are ostensibly sent to these institutions by their family members, police, or their communities for help. Abuse takes place despite the fact that Ghana has ratified a number of international human rights treaties, including the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD), which was ratified in July 2012. The abuse includes denial of food and medicine, inadequate shelter, involuntary medical treatment, and physical abuse amounting to cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment.

The findings by Human Rights Watch were similar to an earlier graphic narration of human rights abuse at the Accra Psychiatric hospital by Anas Aremeyaw Anas.

The Mental Health Act provides for the establishment of a Mental Health Tribunal to oversee, among others, human rights violations. However, implementation of this Tribunal is still in the pipeline. For this Tribunal to function effectively we must train Health Lawyers to help interpret, advocate and enforce the Mental Health Act, and to protect patients’ rights. But according to Doku, Wusu-Takyi and Awakame (2012), "the law faculties of the University of Ghana and Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, do not offer elective courses of study in Health law hence lawyers trained in Ghana qualify without exposure to health law training, let alone mental health law”. So the threat of non-fulfilment of the mandate of the Tribunal or breach of patients’ rights is real.

- Our Criminal Code, 1960 (Act 29) criminalises suicide. Section 57 of Ghana’s Criminal Codes states that, “whoever attempts to commit suicide shall be guilty of misdemeanour”, making suicide and corruption “criminal mates”. Meanwhile, a content analysis of media reports on adolescent suicide in Ghana showed that from January 2001 through September 2014, a total of 44 adolescent suicides were reported; 40 cases were completed suicide and four were attempted suicides. Barely three months ago, a Police Officer in uniform, who is supposed to know the laws of the land better, committed suicide after killing his mother-in-law and two children. If the criminalisation of suicide serves to deter people from attempting the act, then it needs a second look; because suicide is the product of clinical depression and destructive thinking.

In other jurisdictions, the illogicality inherent in the criminalisation of suicide has been recognised and appropriate steps have been taken. For example, The Indian Government was moved to take steps to reform its national health policy when the country’s suicide rate hit 258,000; the highest number of deaths by suicide globally according to the World Health Organisation (2014). The Indian Government decriminalise the act of suicide, ‘with the aim of improving possibilities for discussion and intervention around suicidality’.

Another Burden?

There are fears that the aforementioned legislative issues will add to the catalogue of existing burdens our mental health system is carrying. Already, 3.2 million Ghanaians are estimated to have mental disabilities (disorders); 650,000 are reckoned to have severe mental disabilities. For the treatment of both mild and severe mental disabilities, the country has 600 (demoralised and poorly paid) severe mental disabilities. For the treatment of both mild and severe mental disabilities, the country has 600 (demoralised and poorly paid) Psychiatric Nurses and 12 practicing Psychiatrists; all contained in three under-funded Public Psychiatric Hospitals (all located in the Southern part of the country).

Though the Mental Health Act seeks an orderly resolution of these heavy burdens, it is unlikely that it will achieve this in the foreseeable future. Unless there is flexibility and innovation in our approach toward mental health issues . A notable example is the Public-Private Partnership (PPP) between the Ghana Health Service and BasicNeeds Ghana. Using the mental health and development model, this partnership has made mental health care accessible; providing medicines and counselling in primary care settings (homes) to 43,312 people with mental disorders and epilepsy in the Northern parts of the country and, delivering economic opportunities to families affected by mental illness through 253 self-help groups.

Conclusion

In principle, the Mental Health Act is an essential document which keeps pace with modern developments in the delivery of mental health services, protects the human rights of mentally ill persons and ensures orderly conduct of public and private mental health facilities. But the reality is that, to date, we have ‘mad persons’, male and female, roaming the streets of Ghana naked. Instead of the proper treatment and rehabilitation of these persons, we have a Criminal Code which fails to overtly prohibit all manner of torture against the mentally ill but puts them among tycoons of corruption; and an educational system which cannot nurture Specialised Lawyers to serve as advocates for their human rights.

Author: Ernest Armah is a Social Policy Researcher with passion for service, driving positive results and creating opportunities. Contact: [email protected]

Court dismisses Serwaa Amihere case against Henry Fitz, two others

Court dismisses Serwaa Amihere case against Henry Fitz, two others

Stolen BRVs: Bi-partisan parliamentary probe non-negotiable — Dr. Omane Boamah

Stolen BRVs: Bi-partisan parliamentary probe non-negotiable — Dr. Omane Boamah

Bawumia begins regional campaign tour on Monday

Bawumia begins regional campaign tour on Monday

With great urgency backed by verifiable data, facts and figures dismiss COCOBOD,...

With great urgency backed by verifiable data, facts and figures dismiss COCOBOD,...

EC’s statement on obsolete BVDs discovery “lies, half-truths, pure fantasies” – ...

EC’s statement on obsolete BVDs discovery “lies, half-truths, pure fantasies” – ...

Nalerigu court impound vehicles of DCE, Director of Chereponi district for owing...

Nalerigu court impound vehicles of DCE, Director of Chereponi district for owing...

Cop, 7 others grabbed over $523,000 Gold Scam

Cop, 7 others grabbed over $523,000 Gold Scam

Akufo-Addo’s driver wins Dadekotopon NPP Parliamentary Primary

Akufo-Addo’s driver wins Dadekotopon NPP Parliamentary Primary

Investigate, jail persons liable for GRA-SML contract – Manasseh

Investigate, jail persons liable for GRA-SML contract – Manasseh

Lawyer wins Akan NPP Parliamentary Candidate primary

Lawyer wins Akan NPP Parliamentary Candidate primary