One Saturday morning, one of our classmates, I forget who, reported of having espied one of PERSCO's three carpenters making what looked like a toddler's coffin. Naturally, many of us became curious and wondered just whose tot's casket this could be; just whose beloved little child had met with such raw and untimely death. And so after breakfast, I decided to satiate my curiosity by visiting the carpenter's shed to learn things for myself.

I met the senior carpenter, Mr. Jonathan Agbeko (or some such name, if memory serves me right) who promptly confirmed to me that, indeed, the 5-year-old son of Mr. Debrah had taken suddenly ill and died the previous night. The tot's name was Kwasi Debrah, a sprightly dear little soul.

Almost every one of his students loved Mr. Debrah's little boy. Like most children his age, Kwasi Debrah was nimble and inquisitive. Mr. Debrah was our second and newest Agricultural Science master on campus. He had been posted from Akyem-Oda Secondary School, or some such other institution. At the time of his little son's death, Mr. Debrah had been at St. Peter's for just under two years.

Our other Agric Science teacher was Mr. Obiri, whom we had affectionately nicknamed “Pseudopodia.” The latter nickname had something to do with our study of bacteria. But exactly how Mr. Obiri came by his nickname was not quite clear to me, as he had already acquired it by the time that my classmates and I arrived on campus. About the only other thing that I vividly remember was that during my second year at PERSCO, Pseudopodia had been widely rumored to be seeing the elder sister of one of my classmates, Ernest Obeng, a quite remarkable athlete.

Soon enough, the rumor about Pseudopodia was validated when a handful of us classmates spotted Obeng's sister emerging from Pseudopodia's bungalow one nippy Saturday morning. She had apparently spent the night on campus. We knew Obeng's sister because she was a regular attendee at the annual intercollegiate athletic meet; she also regularly visited her younger brother. Almost every other week, bringing along quite a remarkable amount of goodies which we occasionally shared with Ernest. My immediate-elder sister, Abena Yeboaa, who attended Abetifi Presbyterian Secondary School (APSEC) with Obeng's sister, would also confirm the same to me. My sister would even inform me that, indeed, Pseudopodia had engaged Obeng's sister.

As, of course, was only to be expected, Ernest Obeng endured quite a remarkable level of ribbing from his own classmates, including me; we would wink at him from time to time, particularly when it came time for Agric Science lessons and Pseudopodia was either late or practically nowhere to be found. On such occasions, we would wonder aloud whether Mr. Obiri's absence was due to our classmate's sister having put Pseudopodia to some back-breaking adult task the previous night. For me, in particular, the area of curiosity lay in whether Pseudopodia's conjugal affinity with Obeng's sister had any influence on the grade of our teacher's in-law-to-be in our Agric Science class. There was absolutely no evidence that it did; for Ernest Obeng was just an average student in the course. And on one or two occasions, Pseudopodia even had to remark to the effect that Obeng needed to work much harder if was not to be kicked out of school. In hindsight, Pseudopodia's dating of Ernest Obeng's sister may well have negatively impacted on the academic progress of my classmate.

It was just about the same time that he started torridly dating Obeng's sister that Pseudopodia also announced to us, students, that he had sat for and passed his Advanced-Level General Certificate of Education Examination and would, therefore, cease teaching at PERSCO by the close of the 1977-78 academic year. He would be attending the University of Ghana (or was it the University of Science and Technology?) at the beginning of the following academic year.

Naturally, many of us, particularly those of us who had taken a keen interest in Agric Science, felt wistful about Pseudopodia's impending departure. He had been such an engaging teacher. But, perhaps, most significant of all, I was one of Pseudopodia's favorite students.

“Don't worry, I shall be visiting you from time to time,” Pseudopodia had almost apologetically offered.

Some of us also nicknamed Pseudopodia “Nematodes,” about something to do with organisms in the soil. “Nematodes” sounded to us like “Nima Toads.” Nima was a suburb of Accra, and the “todes” in Nematodes sounded to us like “toads,” that species of the frog family. So to us Form-One students, “Nematodes” simply meant “The Toads of Nima.” Perhaps these toads swamped the open-drainage system of one of the most notorious slums of our nation's capital after heavy downpours.

Kwasi Debrah's death agitated most of my classmates. And for me, in particular, it neither had rhyme nor reason, as it were. For how could such a noble and magnanimous teacher like Mr. Debrah lose his 5-year-old son within the whiff of a breath? Even more perplexing was the fact that at 5 years old, Kwasi Debrah had not committed any of the deadly sins proscribed in the Bible to be taken away so swiftly and suddenly from his loving parents. And even assuming that his parents, like all fallible beings, had done anything untoward in the sight of God, still, what could be the divine justification for punishing the toddler for the sins of his parents?

In retrospect, perhaps Kwasi Debrah's death brought into sharp relief my own mortality, and the absolute and tragic unpredictability of life in general. I had felt morbidly frightened, especially since this toddler's death had occurred barely a year after the reported death of Mark Hanson, our school band's diamond-voiced vocalist. I had gone through the ritual motions of breakfast; the hominy regularly served on Saturday mornings tasted like chaff in my mouth. I had even given my peanut-butter sandwich to somebody who wanted an extra helping of the same. Perhaps my foregoing breakfast on the morning of Kwasi Debrah's death had the edge of subliminal penance to it, in hindsight. Or was this purely my own private prayerful appeal to God to spare me the raw and premature fate of Mr. Debrah's son?

Shortly after Senior Awauah-Kyei had sounded the bell for the end of breakfast, I timidly filed out of the dining hall with some of my classmates and directly headed for Mr. Debrah's bungalow. It stood three blocks down the road from the Form-Five classroom building. After bashfully rapping at the door, the gentleman of the house gingerly cracked the door open to let us in. None of the handful of us present knew exactly where and how to begin the obvious. Interestingly, though, I was quite surprised at how well-composed my Agric Science teacher seemed to be. He seemed to be a strict adherent of the traditional belief that it was patently unbefitting for a man worth such functional designation to cry or weep in such a traumatizing moment of crisis. However, if one took a more careful look into his bloodshot eyes, one definitively came away with the unmistakable impression that Mr. Debrah had, indeed, broken that traditional Akan macho tenet. He appeared to have cried his heart out most of the previous night.

As he briefly narrated, Kwasi had complained of a headache the previous Wednesday or Thursday night and had been taken to the Atibie Government Hospital, some five miles away, the very next day, having also been promptly administered an analgesic. The doctor had prescribed for the toddler some medication which was promptly supplied by the hospital's dispensary. The little boy seemed to be doing fairly well, until Friday night his illness had apparently intensified beyond the strength of his medication.

I remember Mr. Debrah vividly, almost as if the last time that I met him was yesterday. And the reason is simply because he was also the first teacher who drove home to me the practical ineffectuality of an education whose acquired knowledge could not be readily applied to the crucial enhancement of one's livelihood. Mr. Debrah demonstrated this to me when upon marking my first Agric Science quiz paper in his class, he promptly recognized the fact that although I had been advised to specialize in the Liberal Arts, still, I had an uncanny flair for Agric Science, one which, in his expert opinion, necessitated that I add Agric Science to my course load. For not only was I one of the best students in the subject, I also maintained one of the most prolific vegetable beds on the school farm. Mr. Debrah firmly believed that coupled with Chemistry, a subject in which I was quite a formidable student, I should be able to take Agric Science to the “O”-Level and readily acquit myself.

Alas, Father Glatzel, our headmaster, would hear nothing of it. For “Owudo,” about the only way that I could be allowed to take Agricultural Science to the “O”-Level was if I also added Physics to my course load. Needless to say, “Owudo” was simply acting out of professional selfishness, being a physicist himself. The problem here, however, was that I had scored a dismal 45-percent on my Physics quiz just the week before; and other than my good friend Kwame Bediako-Firempong, there was almost nobody else in Form-Three (going on to Form-Four) that I could best in this most abstract of subjects, at least in my opinion. Thus ended what potentially could have shaped me into, perhaps, the greatest Ghanaian farmer.

Indeed, anytime that either Mr. Debrah's name or image – the high forehead and balding head of the 5-foot-10-ish gentleman from Akyem-Oda – flashes through my mind, which is not infrequent, the neocolonialist orientation of the sort of academic curriculum that I underwent during the course of my Ghanaian secondary school education depresses me to no end.

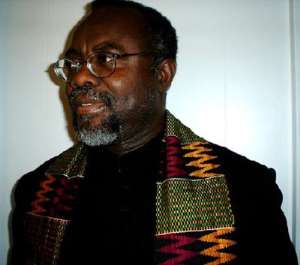

*Kwame Okoampa-Ahoofe, Jr., Ph.D., is Associate Professor of English, Journalism and Creative Writing at Nassau Community College of the State University of New York, Garden City. He is the author of twelve books, including “Dr. J. B. Danquah: Architect of Modern Ghana” (iUniverse.com, 2005). E-mail: [email protected].

#########################################

Akufo-Addo commissions Phase II of Kaleo solar power plant

Akufo-Addo commissions Phase II of Kaleo solar power plant

NDC panics over Bawumia’s visit to Pope Francis

NDC panics over Bawumia’s visit to Pope Francis

EC blasts Mahama over “false” claims on recruitment of Returning Officers

EC blasts Mahama over “false” claims on recruitment of Returning Officers

Lands Minister gives ultimatum to Future Global Resources to revamp Prestea/Bogo...

Lands Minister gives ultimatum to Future Global Resources to revamp Prestea/Bogo...

Wa Naa appeals to Akufo-Addo to audit state lands in Wa

Wa Naa appeals to Akufo-Addo to audit state lands in Wa

Prof Opoku-Agyemang misunderstood Bawumia’s ‘driver mate’ analogy – Miracles Abo...

Prof Opoku-Agyemang misunderstood Bawumia’s ‘driver mate’ analogy – Miracles Abo...

EU confident Ghana will not sign Anti-LGBTQI Bill

EU confident Ghana will not sign Anti-LGBTQI Bill

Suspend implementation of Planting for Food and Jobs for 2024 - Stakeholders

Suspend implementation of Planting for Food and Jobs for 2024 - Stakeholders

Tema West Municipal Assembly gets Ghana's First Female Aircraft Marshaller as ne...

Tema West Municipal Assembly gets Ghana's First Female Aircraft Marshaller as ne...

Dumsor is affecting us double, release timetable – Disability Federation to ECG

Dumsor is affecting us double, release timetable – Disability Federation to ECG