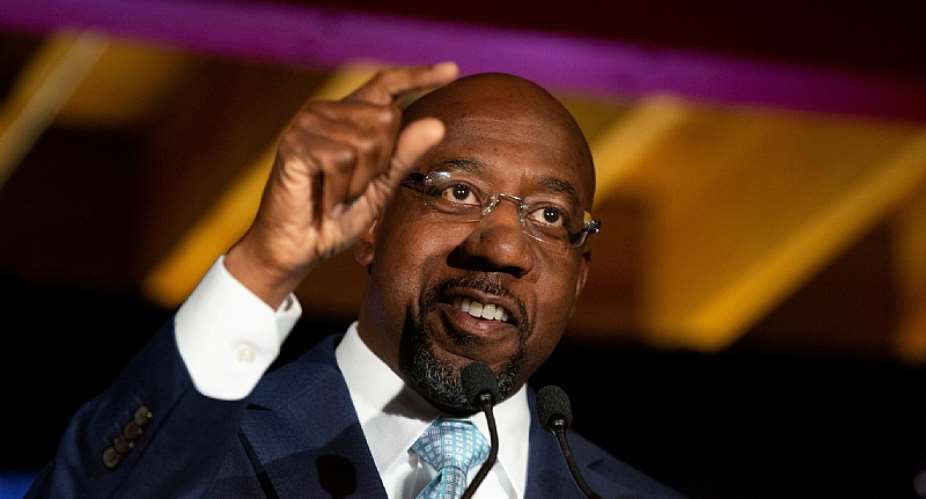

Out of the six new Black candidates for the U.S. Senate, only the Rev. Raphael Warnock of Georgia survived to fight another day. The five others crashed and burned in their respective states, including two with better-resourced campaigns. The Warnock campaign was a long-shot largely ignored by the Democratic Party. Now, however, liberal groups are trying to lay hands on his achievement – as President Kennedy noted, “Success has many fathers, but failure is an orphan”

For the Warnock campaign to win in the January run-off, however, it must avoid becoming the next darling of the American left. In Mississippi, Democrat Mike Espy was turned into a poster child of the New York Times editorial pages. In South Carolina, Democrat Jamie Harrison was seduced by the huge donations of groups seeking to retaliate against incumbent Republican Lindsey Graham.

While other factors played a role in their election defeats, both campaigns faced complication by allowing the candidates to be defined in part by the progressive wing, and both ended in defeat.

Now those same interests are gathering around a Warnock campaign that they once wrote off. His quest was considered too much of a long-shot gamble and most people bet on the campaign of Jon Ossoff, running for the second senate seat in Georgia. His run was more in the southern tradition of Black voters expected to propel white males to statewide office.

On one hand, Warnock may have benefitted from flying under the radar. It allowed him to focus on building a political organization in the Black community and to avoid the stigma of the liberal agenda. On the other hand, he suffered from limited access to capital and technical experts.

Now, the campaign will be solicited by liberal interests seeking to capture him as the new standard bearer – looking to use his network with the folk to serve the interests of the progressive wing. That makes the next two months a very tricky period for the direction of the campaign and for the existential goal of the “Georgia Imperative.”

The Georgia Imperative is a concept to build a sustainable Black political power base in the state. It is a response to the divisive politics and race relations of recent years. To ordinary folk, the lessons of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery; the Michigan militia, and the election of Trump, underscore the intransigence of white supremacy. Under periods of stress, it may only take a tweet to spur people to vigilante actions.

This reality has motivated people to seek out a safe haven in this land -- not an ethno-state as much as a place where they can rely on consistent influence to make laws and run the government. Georgia is able to become such a state. With its large and growing Black population, and its capable political class, it can be the solution to the search for a place.

In Georgia, Blacks can assume the role of a decisive voting bloc. Today, white liberals are eager to interpret the election as evidence of a New York City style coalition transplanted in the South – northern whites, Latinos, Asian, gays, and, oh yeah, the local Black voters. This is a self-serving analysis meant to minimize the dominant leverage of Black Democrats.

A more cogent interpretation would be that Black voters, with the right strategy, constitute a force for a new politics in the South. They are forming a political base with the flexibility to forge alliances of mutual interest with disparate groups.

Clearly, the Warnock campaign needs to appeal to more voters if it wants to win. However, it has probably maxed out the white liberal support in the state. To expand beyond the November turnout – and to nurture an on-going political organization – he will need to show a streak of independence from the liberal agenda.

In the context of Georgia’s politics, that means exploring areas of common interest with conservative white Christians and with agribusiness, among other sectors. That means sensible reconciliation of the interests of moderate Black Democrats with the anticipations of receptive white conservatives.

Warnock, as a Baptist minister, is well-positioned to encourage a “value of life” agenda: end the pandemic, expand Medicaid, reform prison sentencing, train police better, promote responsible gun ownership, reduce abortion rates, encourage racial understanding and investments in education, among other ideas.

In closing, the Rev. Raphael Warnock could be the best hope for Blacks to lay the foundation for the Georgia Imperative. This vision of a Black statewide power base should not override the continued pursuit of equal rights nationally, of course – but the perfect should not be made the enemy of the good.

The quest for a place where Blacks oversee the governance, laws, and police forces has merit. The Warnock campaign should serve as a recruitment magnet to college graduates, skilled workers, educated African immigrants, and independent retirees interested in building this new capital of Black America.

Roger House is an associate professor of American studies at Emerson College in Boston and the author of “Blue Smoke: The Recorded Journey of Big Bill Broonzy.” This commentary is reprinted from The Hill.

Election 2024: Bawumia to conduct house-to-house campaign

Election 2024: Bawumia to conduct house-to-house campaign

Ejisu by-election: Arrest Kingsley Nyarko now – NDC to police

Ejisu by-election: Arrest Kingsley Nyarko now – NDC to police

Urgently address ‘dumsor’ crisis – Organised Labour tells Akufo-Addo

Urgently address ‘dumsor’ crisis – Organised Labour tells Akufo-Addo

24-hour economy will help restore Ghana from turbulent times and empower our wor...

24-hour economy will help restore Ghana from turbulent times and empower our wor...

Bawumia to embark on campaign tour of Western North Region on May 3

Bawumia to embark on campaign tour of Western North Region on May 3

Armed robbers attack Mobile Money agent in broad daylight at Tumu; made away wit...

Armed robbers attack Mobile Money agent in broad daylight at Tumu; made away wit...

May Day: ICU-Ghana warns govt against short-changing public sector workers under...

May Day: ICU-Ghana warns govt against short-changing public sector workers under...

May Day: ECG workers stage walkout against Ashanti Regional Minister

May Day: ECG workers stage walkout against Ashanti Regional Minister

NPP govt bought Ejisu by-election with taxpayers’ money – CPP

NPP govt bought Ejisu by-election with taxpayers’ money – CPP

Ejisu by-election: Arrest and prosecute Kingsley Nyarko over bribery incident – ...

Ejisu by-election: Arrest and prosecute Kingsley Nyarko over bribery incident – ...