When she was approached to make a graphic novel out of Roahld Dahl's The Witches, Penelope Bagieu was pleased to get the chance to adapt one of her favourite childhood books. But she wanted to make some modifications, in particular, addressing the underlying misogyny of a story about witches.

Taking on The Witches was an interesting choice for Bagieu, a self-avowed feminist, who won the 2019 Eisner award (like the Oscars for comics) for the US edition of her book Culottées (translated as Brazen: Rebel Ladies Who Rocked the World), a series of biographies of 30 women from around the world.

Critics have pointed to the sexist undertones in The Witches, with Dahl's witches, who hate children, appearing as normal women, hiding their true identity. “All witches are women,” he writes.

Bagieu talks about addressing the issue, adding her personal (French) touch to the book, and how comics are a real form of literature in France.

(This interview has been edited for clarity, and a version first appeared in the Spotlight on France podcast)

Q: You took the story of The Witches, but you wrote your own dialogue, and you even changed some characters. How much liberty can you take with a classic of children's literature like this?

Penelope Bagieu: That was the big question! All the changes were welcomed, as long as they made sense. I had conversations with Luke Kelly, Roald Dahl's grandson, who's the 'keeper of the temple', if you will. Every time I wanted to change or adapt something to make it suit my story, as long as there was a reason, it was fine.

Q: What do you make of this piece of English literature being given to a French person to adapt?

PB: When I heard from my French publisher that they had an offer to adapt The Witches as comics, my first reaction was, 'Wow, they asked their French editor to do this?' That means we really nailed comics! We are the country of comics.

I think we have a very helpful environment in France for creating comics. It's valued as a form of literature.

We don't have superhero series [like the Marvel comics], where you write stories for a character that already exists, in a like a legacy. You create your own stories, your own characters.

And it's not very hard to be published in France. It doesn't mean that you're going to sell your books, or that you're going to make money. But if you want to write your stories, you can pretty much always find a publisher who's willing to publish you.

So once you pass the barrier of language once were translated, then there's no reason that you can't find an audience outside the borders of France.

Q: Roald Dahl is British, and The Witches is set in the UK. Is there a French touch to your version?

PB: Roald Dahl's books are really part of a lot of French children's libraries. As for the French touch, well, the grandmother in the book is really my grandmother. So she's definitely French.

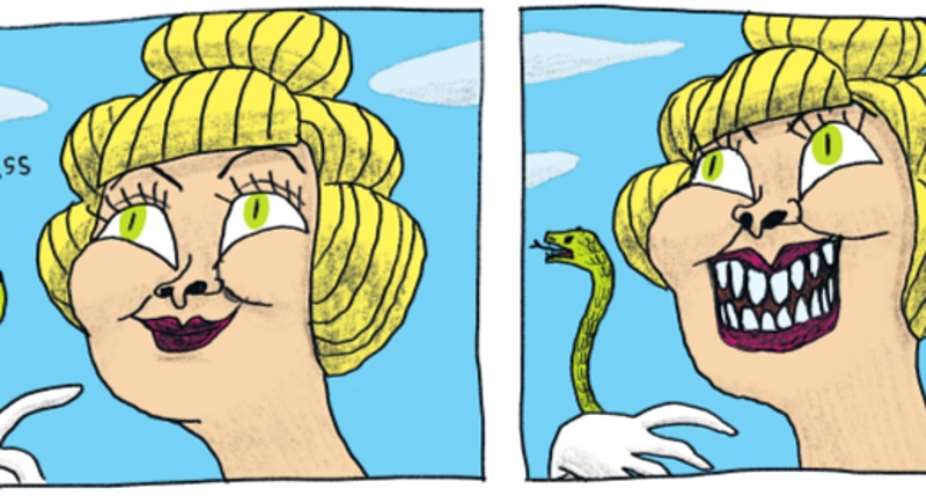

What also changed in my version is that there can be misogynist echo to the idea of women in disguise, hating children. I wanted it to be very clear in my book that the witches—these creatures—they are not women; they just take the appearance of women.

The women in my book are good, and strong, and brave, and funny. And I wanted the part in the story, at the beginning, where the grandmother explains what hunting witches used to be.

You can't talk about witches to children in 2020 without having a word about misogyny.

Q: How did you get into comics? Did you read them growing up?

PB: I was creating comics as a kid without really naming it comics. I was telling stories with characters, with words in balloons and in little frames. But I wasn't really reading comics, mostly because I couldn't find any series in which I could identify with any of the characters.

I know now that it was because there were no girls. The French comics world was really a boys club, because the production was aimed at young boys, and these little boys grew up to become comics artists.

It took a while for women to arrive in this world. A lot of that happened because of Japanese anime and manga, actually. Then a generation of girls started reading and writing their own stories, and creating comics.

That's a generation just a little after me, but I was always writing and drawing comics, even though it took me maybe 30 years to finally realise that it was comics.

Q: What is it that you can do with comics that you can't in another medium?

PB: You don't have to show everything. You don't have to explain everything. So if you want to address a difficult question, like war, or social issues, it's a great way of addressing the subject without having to be too visual. You can decide to just show glimpses of things.

Q: You wrote and illustrated a series of biographies of women, Culottées (Brazen, in English). What does it do to render the stories in comics?

PB: I knew that the book would probably end up in children's hands, so I had to find a way to talk to them about civil wars and domestic abuse, because some of these women had very tough lives. And you don't want to elude and to get rid of those parts of the story.

For instance, there's a story in my book about Phoolan Devi, an Indian activist, who was raped multiple times as a child, and abused by her husband, to whom she was married at the age of nine. You can't just erase that part of her story, because it is so much a part of her.

Her husband would take her into a little cabin at the end of the garden to molest her. So I just show the cabin from the outside, in a very quiet afternoon. You see the cabin, and you know what's going on inside, which is a million times worse than actually showing it.

To me, comics is a perfect medium. You can bring people to read about subjects they wouldn't think they would be interested in. The Trojan horse power of comics is like: 'Oh, here's a fun story about a little girl growing up', and boom, it's Persepolis, and before you know it, you've read 300 pages about that about the Iranian Revolution.

Q: Persepolis, the autobiographical graphic novel by Marjane Satrapi, was published in 2000. What impact did it have on your work?

PB: A lot. It was really unusual: it was in black in white, a long story, and the autobiography of a girl. She was talking about her makeup and her boy issues. But the historical background [of the story taking place during the Iranian Revolution] was so intense. I thought, 'Wow, so you can also talk about this in comics?'

And the immense commercial success of this book opened the door to so many, not just women, but artists, who were then able to tell their own stories. Suddenly, it was possible.

Q: As a female comics writer in France, are you able to just be a comic book writer, or is it always with a modifier, like 'feminist' or 'girly' comics author?

PB: I have seen a difference between when I started maybe 15 years ago, and today. But there are also subjects, focused on women, that we have to address. Women in comics have to be the trailblazers, because for 50 years these were subjects that weren't really important.

This interview was produced for the Spotlight on France podcast.

Akufo-Addo commissions Phase II of Kaleo solar power plant

Akufo-Addo commissions Phase II of Kaleo solar power plant

NDC panics over Bawumia’s visit to Pope Francis

NDC panics over Bawumia’s visit to Pope Francis

EC blasts Mahama over “false” claims on recruitment of Returning Officers

EC blasts Mahama over “false” claims on recruitment of Returning Officers

Lands Minister gives ultimatum to Future Global Resources to revamp Prestea/Bogo...

Lands Minister gives ultimatum to Future Global Resources to revamp Prestea/Bogo...

Wa Naa appeals to Akufo-Addo to audit state lands in Wa

Wa Naa appeals to Akufo-Addo to audit state lands in Wa

Prof Opoku-Agyemang misunderstood Bawumia’s ‘driver mate’ analogy – Miracles Abo...

Prof Opoku-Agyemang misunderstood Bawumia’s ‘driver mate’ analogy – Miracles Abo...

EU confident Ghana will not sign Anti-LGBTQI Bill

EU confident Ghana will not sign Anti-LGBTQI Bill

Suspend implementation of Planting for Food and Jobs for 2024 - Stakeholders

Suspend implementation of Planting for Food and Jobs for 2024 - Stakeholders

Tema West Municipal Assembly gets Ghana's First Female Aircraft Marshaller as ne...

Tema West Municipal Assembly gets Ghana's First Female Aircraft Marshaller as ne...

Dumsor is affecting us double, release timetable – Disability Federation to ECG

Dumsor is affecting us double, release timetable – Disability Federation to ECG