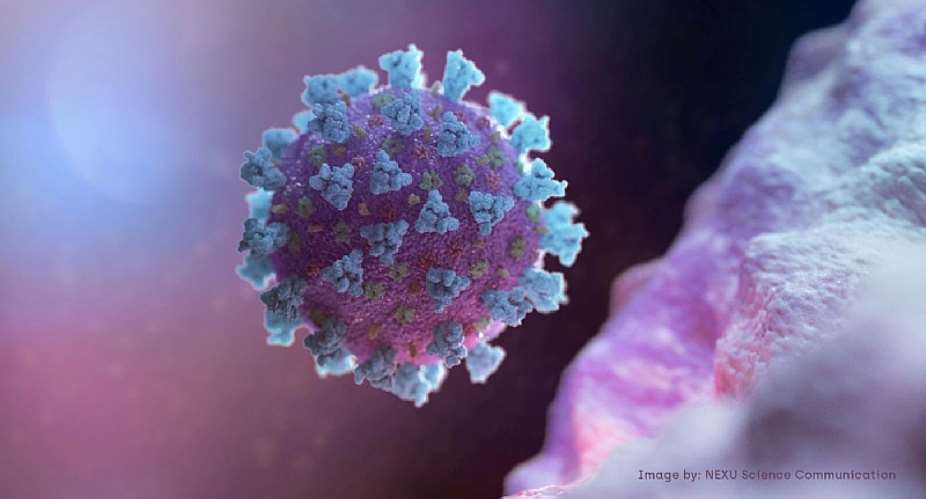

The health and economic impact of the deadly and fast-spreading novel coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic has received significant public attention. In the midst of the pandemic, a number of personal and public health precautionary measures have been suggested by the World Health Organisation (WHO) and other public health experts to reduce person-to-person spread and ultimately, contain the virus. One of such protocols is social or physical distancing. Social distancing, according to WHO, describes a set of non-pharmaceutical measures that are taken to prevent the spread of an infectious disease by maintaining a physical distance between people and reducing the number of times people come into close contact with each other. Similarly, the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) explains social distancing to mean remaining out of congregate settings, avoiding mass gatherings, and maintaining physical distance of approximately 6 feet or 2 meters from others, when possible, to forestall the spread of communicable diseases such as COVID-19. In a bid to enforce a strict compliance of the social distancing protocol and limit the spread of the virus, many governments around the globe have imposed lockdowns, stay-at-home, shelter-in-place and curfews on its citizens.

Fundamentally, the call is for all of us to remain apart from one another physically, and to act as if you have the virus and approach other people as if they have it too. It is a call for us to actively and purposefully maintain a strict personal space around ourselves to the extent that we should feel uncomfortable and threatened when others intrude. Though the call for social distancing is a good one and promises to be one of the most effective non-pharmaceutical ways to contain the spread of the virus, there are many psychosocial injuries that the social distancing compliance is likely to cause to the people of Africa and their communal norms of life. The focus of this article is to highlight some of the psychosocial pains of social distancing enforcement in Africa. I will particularly discuss how, in the face of African communal norms, the strict observance of social distancing may affect people’s sense of being/personhood and spirituality.

The concept social conjures much broader and deeper meaning in Africa than its everyday use in psychological research, particularly in western societies. In western scholarship, the term social is generally used to refer to more atomistic individuals acting together, while society or community is used to mean the aggregated sum of atomistic individuals comprising it. In contrast, the African view of social and society or community refers to a thoroughly fused collective. Thus, social conveys the African communal sense of interdependence and belonging. While many westerners are likely to have much less psychosocial problems complying with the social distancing measures, because of their daily practice of personal space, many Africans are likely to find social distancing compliance a huge challenge because of the near absence of personal space in their everyday communal life. For example, while westerners are more likely to congregate in public settings such as shopping centers, movie theaters, stadiums and religious temples and yet maintain significant personal space and avoid hand-shaking, particularly with strangers or less intimate persons, Africans are more likely not only to congregate in these public places and maintain close contact with others, but also, they are likely to shake many hands, hug people tightly, including friends, relatives and sometimes even strangers, and maintain small to no personal space. This is because connectedness of people in Africa to others and the community is not a value belief about how things ought to be, but instead, it is an ontological experience about how things are. Communal life is a matter of culture and survival in Africa.

Thus, given the African communitarian living and embedded interdependence in public spaces, an imposition of a lockdown and social distancing protocol is likely to be resisted, downplayed and/or easily forgotten by people when they have the chance to interact in public spaces such as market places and on public transport/buses (trotro). A strictly enforced social distancing protocol may thus engender psychosocial pain among the citizenry— the pain of not being allowed to freely do in public, the things that bring psychological and communal satisfaction to the individual. One such area of communal life that social distancing compliance is likely to affect in Africa is people’s spirituality. Research suggests that people in Africa do not live interdependently and derive belonging, warmth, respect, value, meaning and purpose, but they also desire to experience a sense of transcendence by maintaining harmony and unity with an ultimate being. Consciousness in Africa operates in three overlapping areas— people in Africa are self-conscious, socially-conscious and cosmically-conscious. In all aspects of their lives, Africans feel at home within their lives, in their relationship with others and with cosmic

dimension of being. Thus, connectedness serves as the glue that holds the self, others, nature and God in a cosmological balance. As long as this balance is maintained, in the worldview of the African, there is wellness and mental health. This means that a strict enforcement of social distancing measures is likely to have impactful psychosocial consequences for people’s religious and spiritual life. Though spirituality is supposed to be an individual’s private belief system, in Africa, spirituality is a public activity. For example, it is not uncommon to find religious people in the parks, classrooms, bus terminals, mountain tops and other public spaces publicly and loudly proclaiming their faith and spirituality in the form of preaching and praying. Social distancing means such people will not be able to do this for some time. The pain of not being able to appear in public spaces to proclaim one’s belief, and to experience a sense of transcendence by maintaining harmony and unity with an ultimate being, may have psychosocial and mental health consequences such as perceived lack of control over one’s life, anxiety, decreased sense of spirituality, loneliness and depression. This may account for the reason for which some religious leaders and their congregants in Ghana are reported to have defied the imposition of restrictions order to congregate in public spaces for worship. Such reactionary behaviours may represent some of the ways individuals adopt to regain control over their lives.

Another area that the social distancing measures may disrupt in Africa is people’s sense of being (personhood) as well as their sense of community and belonging. Psychological and philosophical scholarship in Africa have noted the important conceptual distinction between a human being—a biological entity—and a person—a social, moral and metaphysical entity. In the African worldview, a person is defined with reference to his/her community. One of Africa’s prolific scholars, Professor John Samuel Mbiti, aptly sums up the person-community relationship in Africa in a statement: “I am because we are, and since we are, therefore I am.” In Southern Africa, the concept of “Ubuntu” is traditionally employed to describe the person-community relationship and express the African philosophy of “I am because we are.” Ubuntu describes the relational nature of personhood and humanity towards others— knowing one’s fellow human beings and taking a keen interest in their well-being. There is a pervasive psychological awareness in Africa that a person is a person because of his/her inextricable and dialogical connection with others in the community. This implies that there is a social and moral component of African sense of personhood. In the African worldview, an individual can be a human being without being (becoming) a person or attaining personhood. As Professor Kwame

Gyekye persuasively argues, there are certain fundamental norms and ideals to which the conduct of a human being, if he is a person, ought to conform in Africa. One of such essential norms and ideals is the African sense of belonging and communal life.

The African sense of personhood and belonging to the community is so ubiquitous and significant that the primary unit of African consciousness can be said to revolve around communal relations and interdependence. Thus, the imposition of restrictions on everyday communal activities such as hand-shake, close contact interactions, social and public congregations, interpersonal face-to-face conversations, religious activities and family visitations may significantly negatively impact Africans sense of belonging and community, as well as their psychological well-being and mental health.

Communal life in Africa is more than a culture; it is also a matter of survival. People need to take public transport and mingle with other passengers in often packed buses to work, and move in crowded cities and market places. The highly contagious nature and ravaging effects of COVID-19 makes social distancing an inevitable part of the African life. However, the communal culture of African people makes it incumbent on African governments to move beyond the imposition of legal restrictions and social distancing orders to concentrate its effort on intensive and far-reaching psychological education that teaches people alternative (positive) ways of life in this crisis moment. These may include advising people to check up on friends and family regularly so they can keep social contact, speak with them on the phone, send text via SMS and social media messaging platforms throughout the day and make video calls, if they can, to ensure that they are not getting too isolated The media should also avoid sensational journalism, “infodemic” and misinformation, and rather focus its attention on educating the masses not only on the need to observe social distancing, but also and most importantly, the temporariness of the social distancing protocol and the collective health benefits it offers to the African community. Learning a “new normal” has never been easy, but with time and right information, things will get better. When people are well informed and/or have the right information regarding why they should act in a particular way, they are more likely to make sacrifices and adjust their daily lives with less or no psychological consequences. Let us all do our part to contain the spread of COVID-19 while reducing the associated psychosocial pain of social distancing.

Stephen Baffour Adjei, Ph.D.

Social and Human Development Psychologist Lecturer, Department of Interdisciplinary Studies Faculty of Education and Communication Sciences University of Education, Kumasi Campus

Email: [email protected]

Togo leader Gnassingbe follows father's political playbook

Togo leader Gnassingbe follows father's political playbook

NDC panics over Bawumia’s visit to Pope Francis

NDC panics over Bawumia’s visit to Pope Francis

EC blasts Mahama over “false” claims on recruitment of Returning Officers

EC blasts Mahama over “false” claims on recruitment of Returning Officers

Lands Minister gives ultimatum to Future Global Resources to revamp Prestea/Bogo...

Lands Minister gives ultimatum to Future Global Resources to revamp Prestea/Bogo...

Wa Naa appeals to Akufo-Addo to audit state lands in Wa

Wa Naa appeals to Akufo-Addo to audit state lands in Wa

Prof Opoku-Agyemang misunderstood Bawumia’s ‘driver mate’ analogy – Miracles Abo...

Prof Opoku-Agyemang misunderstood Bawumia’s ‘driver mate’ analogy – Miracles Abo...

EU confident Ghana will not sign Anti-LGBTQI Bill

EU confident Ghana will not sign Anti-LGBTQI Bill

Suspend implementation of Planting for Food and Jobs for 2024 - Stakeholders

Suspend implementation of Planting for Food and Jobs for 2024 - Stakeholders

Tema West Municipal Assembly gets Ghana's First Female Aircraft Marshaller as ne...

Tema West Municipal Assembly gets Ghana's First Female Aircraft Marshaller as ne...

Dumsor is affecting us double, release timetable – Disability Federation to ECG

Dumsor is affecting us double, release timetable – Disability Federation to ECG