Davina Morris examines the ongoing debate over Britain's acquisition of priceless African artefacts

FANS of the '90s BBC comedy show The Real McCoy may remember the sketch when pro-African activist Babylon (played by Felix Dexter) urged black Britons to head down to the British Museum with a big bin liner to “tek back your tings!”

Though the sketch was intended to be comedic (and it was), it highlighted the ongoing issue of whether British institutions should return the many cultural items they possess that were taken from Africa years ago.

The British Museum, the British Library and the Victoria and Albert Museum are just a few of the British institutes that hold items that were looted during the invasion of Magdala in Abyssinia (now Ethiopia) in 1868 by a British punitive expedition army. In short, the British won the battle and then proceeded to loot countless items from the defeated ruler's palace and from churches. In fact, it has been widely reported that it required a staggering 15 elephants and 200 mules to carry the loot, which included treasures and religious manuscripts.

Some of the loot was auctioned – the money raised was distributed amongst the British troops – some artefacts were presented to Queen Victoria, and others remain in public collections in venues such as the aforementioned British institutes, as well as in the Royal Library in Windsor Castle.

Four years after the looting of Magdala, the then British Prime Minister William Gladstone conceded that he “deeply regretted that those articles were ever brought from Abyssinia and could not conceive why they were so brought.”

Still, over a century on, the debate continues to rage about Britain's acquisition of numerous African treasures.

There have been many calls for the return of these items from both individuals and organisations that accuse these institutions of holding stolen property.

One such protester is Ras Seymour Mclean, London Chaplain of the Ethiopian World Federation Inc. Jamaican-born, London-based Mclean was jailed in the 1980s for the theft of over 2000 Ethiopian manuscripts from British libraries, which he intended to return to Ethiopia. His story was later turned into a Channel 4 film called The Book Liberator.

Today, the outspoken activist says he would do the same thing again “even more positively,” and continues to insist that the British should return the Magdala treasures to Ethiopia.

“The looted Ethiopian manuscripts were taken from a national church,” Mclean says. “Stealing from a church amounts to sacrilege. Prime Minister Gladstone held the same views, hence his lamentation over the looting. The manuscripts contain the spiritual and cultural history of black people of Africa all over the world and they should be returned.”

Historian and professor Richard Pankhurst – son of suffragette Sylvia Pankhurst – and one of the founding members of AFROMET (Association For the Return Of the Magdala African Treasures) mirrors these sentiments.

“These treasures belong in Africa, as that's where they were looted from,” says British-born Pankhurst, who now resides in Ethiopia and specialises in Ethiopian studies. “People of those countries should be able to see the treasures their ancestors created.”

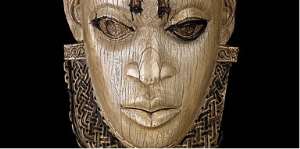

However, the British Museum – which possesses African artefacts including bronzes from Benin, Nigeria and Ethiopian tabots (that can only be viewed by priests and not by the general public) – feels that it is necessary for these items to be represented in their collection.

“It is not the case that all African material in the Museum's collection is 'looted,'” says Hannah Boulton from the British Museum. “We feel it is essential that the diverse and varied cultures of Africa are represented in the collection so that our international audience can understand the impact of African material culture on the wider world.”

But Robin Walker, author of the acclaimed black history book, When We Ruled, dismisses this notion, insisting that British museums haven't done enough to market the African treasures they possess.

“One has to ask oneself: What has Britain ever done to popularise these artefacts? What exhibitions have they staged to urge the black British community to go and see them? They've done nothing. Other than the Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, I can't think of any other British museum that has used the African artefacts it holds to inform either the black or non-black communities about African history.”

Walker also refutes the suggestion – one that has cropped up several times in this debate – that the artefacts in question are better looked after in Britain than they would be if they were returned to Africa.

“The Benin bronzes were plundered from Benin palace in 1897,” he explains. “Until the items were plundered, the people of that region were perfectly capable of looking after their items – they had done so for centuries. So why would they not be able to look after them now if they were returned? You have to hand it to whoever would put forward that kind of argument. It's like saying a thief would be better at looking after your stuff than you would.”

Professor Pankhurst agrees: “I cannot speak for all of Africa, but as for Ethiopia, I know there are at least two libraries and three museums that could house the loot taken by the British from Magdala. And if any African country does not have adequate storing facilities, the West could now start building suitable museums in Africa.”

Still, it seems that it's not as simple as these British institutes just handing over the African treasures they possess. Even though, in 2008, Ethiopian President Girma Wolde-Giorgis requested that British institutes holding looted Ethiopian cultural treasures return them, apparently it's not that straightforward.

According to Oliver Urquhart-Irvine of the British Library – which has a number of Ethiopian manuscripts in its collection – law stipulates that they can't just give back the looted items.

“The history of what happened [in Magdala] is quite clear… but the issue of restitution is a matter for the British government,” Urquhart-Irvine says. “The British Library is governed by the British Library Act of 1972. Under that act, we don't have any power to de-accession these items. This is a matter that has to be dealt with between governments.

“There was a request for the return of the items in 2008 by the [Ethiopian] President. We responded, confirming receipt of the request and we indicated some of the good work that was going on [in the British Library]. We look forward to hearing from the Ethiopian government about ways we can take forward collaborations. We've loaned items to the African Zion exhibition in the United States and we've had academic collaborations with Professor Richard Pankhurst, so we are open to collaborative projects. As long as we have the legal obligation to look after these items, we'll do our best to do so, and make the items as available as possible.”

While items in the British Library are, indeed, available for access to the general public, access to the Royal Library in Windsor Castle is obviously more restricted.

The Royal collection contains six Ethiopian manuscripts, which were presented to Queen Victoria in the 19th Century. And while a Royal Collection spokesperson told us that the manuscripts are “made available for study in the Royal Library,” it's not every Tom, Dick or Harry that will get the chance to take advantage of this opportunity.

“Serious scholarly applications can be made to view specific, unique items held in the Royal Library,” the spokesperson explained. She added: “The Royal Collection is held in trust by The Queen as Sovereign for her successors and the Nation. There has been no formal request for their return by the Ethiopian government.”

And if there was?

“This would be a matter for Her Majesty The Queen.”

Of course. So it would seem that Her Majesty has no immediate intention of handing back the manuscripts. Perhaps it is time for African governments to be more vocal about this issue, if there is to be any chance of British institutes returning looted African treasures.

However, there have been some items returned. In 2003, a German museum handed back to Zimbabwe a soapstone carved bird after 100 years. Two years later, Ethiopia successfully fought for the return of one of its national religious treasures, the Axum Obelisk, which had been looted by Italy nearly 70 years earlier. And in 2009, French President Nicolas Sarkozy returned to Egypt stolen ancient relics that had been chipped off a wall painting in the ancient Egyptian tomb of Tetiky centuries earlier.

Still, many feel that this shouldn't be an issue of government intervention, but more an issue of right and wrong. To them, there is an uncomfortable irony in the fact that there is a law that prevents the British Library from returning looted Ethiopian manuscripts – and yet the original looting of the Magdala treasures, though condemned by the then British Prime Minister, was not ruled as unlawful. The logic seems odd: it was ok for the goods to be looted but it's not ok for them to be returned?

Still, organisations like AFROMET remain dedicated to the cause of retrieving these priceless treasures and seeing them returned to Africa. Though some people fail to see the importance of ancient artefacts, arguing that Africa is blighted by more serious issues (like the much-publicized problems of poverty and AIDS), many feel that culture and heritage are equally significant matters. As Professor Pankhurst concludes: “I feel that culture is important – and can help all aspects of independence, self-respect and development. A country devoid of its culture is ill-equipped to face other problems.”

Should Britain return stolen African treasures? Tell us what you think. Visit http://www.voice-online.co.uk

France kicks off May Day rallies a year after pensions backlash

France kicks off May Day rallies a year after pensions backlash

EU probes Facebook, Instagram over election disinformation concerns

EU probes Facebook, Instagram over election disinformation concerns

Kenya’s devastating floods expose decades of poor urban planning and bad land ma...

Kenya’s devastating floods expose decades of poor urban planning and bad land ma...

May Day: We’re committed to giving you brighter future – NDC assure workers

May Day: We’re committed to giving you brighter future – NDC assure workers

Kasoa: Military officer shot dead over land dispute at Millennium City

Kasoa: Military officer shot dead over land dispute at Millennium City

'It's a digrace for Akufo-Addo gov't' – Aduomi on vote-buying allegations at Eji...

'It's a digrace for Akufo-Addo gov't' – Aduomi on vote-buying allegations at Eji...

Yagbonwura was never asked to stand and greet President Akufo-Addo – Chieftaincy...

Yagbonwura was never asked to stand and greet President Akufo-Addo – Chieftaincy...

Ejisu by-election: We must ‘aggressively’ reach out to disgruntled NPP members –...

Ejisu by-election: We must ‘aggressively’ reach out to disgruntled NPP members –...

We’ll bring back Aduomi to NPP – Stephen Ntim

We’ll bring back Aduomi to NPP – Stephen Ntim

Ejisu by-election: Provisional results so far

Ejisu by-election: Provisional results so far