It has long been my opinion that our ancestors were rather more in touch by sea than generally allowed by most sea-history authorities. To that end, a number of articles that emphasise possible African connections have been written by me and posted online on various sites. This is one of them and is more or less a follow-up to “West Africa & the Sea in Antiquity” plus “West Africa & the Atlantic in Antiquity”

There are other things to be noted. All the references are in the body of the text. Also what are often seen as Before Christ (= BC) dates are termed Before Common Era (= BCE) in these pages. Those dates generally expressed as Anno Domini (= Year of Our Lord [= AD]) are now Common Era (= CE).

Did They?

When researching for this article, the material was found to frequently involve a number of consistent features. One is just how much Africans feared the sea and this is especially persistent. So too is how particularly un-seaworthy African vessels were.

A fear of the sea in that of Africa that is Egypt in the northeast is touched on by such Classical writers as Plutarch (1st /2nd c. CE Greek) ,Porphyry (3rd c. CE Greek),etc. To this is added what another Classical writer in the form of Strabo (1st c. Before Common Era [= BCE] Greek) saying Africans above the Horn only seem to have sailed every c. 260 years. Of east Africans from below the Horn of Africa, al-Idrissi (12th Common Era [=CE] Magrebi) wrote they seemingly had no ships.

Further south still in east Africa but still on shores facing the Erythraean Sea (= western Indian Ocean) we approach what are called sub-tropical waters. It is said by numerous expert opinions that non-powered vessels cannot operate in such as these seas of the western parts of the Indian Ocean Region (= IOR).

Georg Buhler (Sacred Books of the East 1879) shows the Laws of Manu (5th c. BCE?) attest codification of the basic tenets of the Indian religion named Hinduism. Manu puts the Hindu priests called Brahmins going to sea alongside incendiaries, eaters of food given by sons of adulteresses, perjurers, etc. James Hornell (Water Transport 1946) says overseas journeying is still strongly objected to by Brahmins. We also note if they did so, they undergo elaborate penances to pay for their “sins”.

George Hourani (Arab Seafaring on the Indian Ocean in Ancient & Early Medieval Times 1995) says early Caliphs at Baghdad (Iraq) tried to prevent Arabs from going to sea as it was unnatural for Muslims to do so. It was said of the Mediterranean to “Trust it little…fear it much”. Arab crews described going from the Red to the Erythraean Sea as going through Bab el-Mandeb (= Gate of Tears). Those on the Atlantic Ocean termed it Bahr al-Zulamat (= Dark Sea).

Egypt faces the Mediterranean Sea in the north and the Red Sea in the east. Alessandra Nibbi (Revue D’Anthropologie 1995; Discussions in Egyptology 2002 & many other works) has brought up the matter of whether Egyptians ever went to sea and cites Strabo (1st c. BCE Greek) saying Egyptians feared both the sea plus sailors. James Hornell (Water Transport 1946) cited Plutarch (1st c. CE Greek), Porphyry (3rd c. CE Greek), etc, saying Egyptian priests shunned the sea.

These taboos may just be giving a religious veneer to the kind of fear already alluded to as present in parts of Africa and still with those parts of east Africa facing the IOR, we now are close to what Denis Montgomery (Seashore Man & African Eve 2005) described as subtropical waters. Montgomery (ib.) plus others are of the opinion that such non-powered watercraft as the west African dugout-canoe just cannot operate in such dangerous seas. Moreover, the peoples native to these southern parts of Africa those we will term as the Khwe (= San= Bushmen) are confidently stated not to ever have fished from boats, indeed never to have used boats at all.

This will mean they would not have ever learnt how to cope with these dangerous sub-tropical waters seen too off the shores of the western side of southern Africa. Bantu is the term descriptive most of the Black population of southern Africa and they are generally deemed not to have reached any part of western South Africa till the 1850s (esp. at Cape Town), so they also cannot have had much dealings in these seas off southwest Africa.

Further is that here was what the Portuguese called the Cabo da Tormentosa (= Cape of Storms) epitomised by the fierce giant that Luis de Camoes (16th c. Portuguese) described as warning foreign sailors away from the shores of such as Table Bay in western parts of South Africa. Camoes named this giant as Adamastor who particularly manifests himself as ferocious thunderstorms. A bit further north is not only the circa (= ca) 1000 mile stretch of the Namib Desert but also a section once called the Skeleton Coast. This name arose from the dangers that the swell of the seas that led to so many shipwrecks of well-built wooden European ships. The term of Skeleton Coast comes from the fact that so many skeletal remains of the ships and/or skeletons of the humans of dead crew plus passengers littered the beaches.

If so many well constructed ships from Europe were subject to these numerous wrecks, what chance for the west African dugout-canoe so frequently described as fragile? The more so in the light of the near-absence of the good harbours that would so facilitate commerce along the shores of west Africa.

Europeans from at least the time of Marco Polo (13th c. Italian) have been somewhat less than impressed by the vessels of Africans. Those of what is called sewn-plank construction were criticised by Polo plus other Europeans. They are mainly from east Africa facing the Erythrean Sea (= western Indian Ocean). James Bruce (18th c. British) in Ethiopia probably epitomised this in a vessel that was “crazy”.

A number of the European reports about canoes in west Africa are given by Stewart Malloy in the avowedly Africa-centred/Afrocentric book titled “Blacks in Science” (ed. Ivan Van Sertima 1983). He quotes remarks by Mungo Park (18th c. British) plus Rene Caillie (19th c. French) noting canoes they came across on the Niger and/or some of their tributaries. Park says a movement by one person aboard a dugout that he was in overturned the vessel. Caillie was in one that was long, narrow and very leaky plus that every time they moved, water swept over the gunwales. Many reading this will be familiar with these scenes of badly-made African canoes overturned so easily by Tarzan in Hollywood films.

From Angola going north to that part of west Africa facing the Atlantic Ocean called the Gulf of Guinea and then up to Morocco was a coastal element that Leo Frobenius called the Northwest Atlantic Culture. Unfortunately, Frobenius (The Voice of Africa 1913) was dismissed as a fantasist by Donald Harden in the British journal called Antiquity (1941). Nor was there ever this unitary political entity that Frobenius envisaged along the coasts of west Africa from Angola to Morocco.

The more so that keeping in touch would mean that going south from Guinea meant taking reportedly fragile canoes against prevailing currents according to Robert Smith (Journal of African History 1970). In any case, messrs Hair, Jones & Law (Barbot on Guinea 1999) say that a statement by Pieter de Marees (17th c. Dutch) that might be thought to give support for Frobenius is simply erroneous. Also the foodstuff called kankey that Marees says was taken south-going from Guinea to Angola because it did not spoil in the sea-air is simply dismissed by the same three authorities

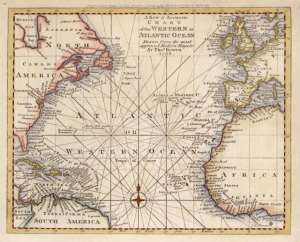

If going south from Guinea would lead to problems for west African canoes, what then of going west from Guinea? This would mean these same canoes being taken out-of-the-sight-of-land (= ootsol) on to the open Atlantic Ocean. Such voyages were ruled out by Christopher Columbus (15th/16th c. Italian working for Spain) on grounds of sheer distance. Further problems arose in that part of the Gulf of Guinea called the Bight of Benin to judge from the doggerel cited by Sir Alan Burns (History of Nigeria 1968) as “The Bight of Benin, few come out but many go in”.

On the question of Africans being scared of the sea, this is reported by such as the French opinions quoted by Roy Bridges (Africa & the Sea ed. J.C. Stone 1985). Another source would be the British sea-captains cited by Robert Smith (Journal of African History 1970). Smith (ib.) also noted attempts at going south of that portion of west Africa facing the Atlantic called the Gulf of Guinea. He further says that voyages going south from Guinea went against prevailing currents. Those going west would not only mean taking canoes on to the open Atlantic and those reaching the far side of the Atlantic were ruled out on grounds of distance (esp. in such vessels).

In what is labelled Guinean west Africa by Robin Walker (When We Ruled 2006) there occurred a number of traits noted in “Between the Sea & the Lagoons…” plus “Some Ibo Burial Customs”. This was by messrs. Law (online) and Thomas (1927) respectively. Law (ib.) cited cultural reasons for Guineans not going to sea that included religious taboos and Thomas (ib.) take this further are such taboos of just above.

The material in “Between the Sea & the Lagoons: The Interaction of Maritime & Inland Navigation on the Pre-Colonial Slave Coast” was by Robin Law (online). He touches on cultural traits having among them religious taboos about not going to sea. More specific are “Some Ibo Burial Customs” by Northcote Thomas (Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute = JRAI 1927). His mention of Ibo priests not being allowed to travel in canoes clearly parallels what was said above about Hindus not being allowed to travel in ships.

An opinion apparently starting in the 18th according to “Exploration in the World” by Pamela White et al (2003) seems to indicate Europeans regarded the narrow channels between mainland Guinea-Bissau and the Bissagos Islands too treacherous to navigate. Another group of islands is the small archipelago called the Cape Verdes. These Cape Verde Islands were thought by messrs. Reclus (The Earth & Its Inhabitants 1892) and Lacroix (Africa in Antiquity 1998) to be unreachable by west African canoes. Elysee Reclus (ib.) says this was because they would be swept back to the nearest coast that means the shores of Senegal some 300/350 miles away.

Senegal has been joined politically in the past with neighbouring Mali and briefly following independence from France. One past occasion was in the Malian Empire ruled by a Mande-speaking dynasty. Yet another three authors tell us that it was impossible for west Africans to have reached the earlier Olmec-era Mexico (see West Africa & The Atlantic in Antiquity online at stewartsynopsis line & elsewhere). For a later period, we have seen that this was ruled out on the authority of no less than Columbus.

In any case, when it comes to the Mali that is so constantly being described as poverty-stricken did it ever had the wherewithal to have provided the fleets that al-Umari (14th c. Syrian) says were sent by Mali to find the other side of the ocean? The account by al-Umari is called here The Returned Captain for reasons to be seen below. What can be said immediately is that our Returned Captain certainly never made it according to what is said by al-Umari.

Mali would have to have had the resources to equip 400 vessels on the first expedition and 2000 more for the second one according to al-Umari. Quite apart from this, can we believe that there ever were this many vessels from any Niger-River region? Moreover, Law (ib.) is one of those attributing the appearance of the coastal trading to the first known Europeans there, the Portuguese.

Van Sertima gives the name of the Malian Emperor that sent these west Africans on to the Atlantic as Abubakri II. Unfortunately, the Umari account nowhere gives the name of Abubakri of either I or II. Moreover, the story seems unknown to the griotic/oral-lore tradition of the Malian griots/djellis (historians/story-tellers).

Another contribution to the online encyclopedia called Wikipedia accessed 28/6/07 (= Abubakri A, as opposed to Abubakri B [accessed 17/7/07]) tells us that the story seems unknown to the griotic/oral-lore of the Malian griot/djelli. Van Sertima (ib.) regards the professors of the Sankore or University at Timbuctoo (Mali) as the crème-de-la-crème of western Islam and as providing the intellectual basis of the geography behind the Malian expeditions. This does not appear to greatly impress the author of Abubakri-A when describing the Sankore as the “so-called” University and also places his use of the term of professors between inverted commas that usually means equivocation at the very least.

At best, the notes to Abubakri-A seemingly indicate a story that may be no more than a mix of migration plus morality tale. Morality-tales abound in such as “Folklore in the Old Testament” by Sir James Fraser (1920). This one has it that the failure of the first Malian expedition and one surviving ship was a warning from Allah that meant that the second fleet led by Abubakri himself was completely sunk for having defied the divine warning. In any case, is the single returning ship any more than the worldwide folkloric device having a survivor so that the tale can be told. The more so it has another nautical parallel from the northeast on the other side of Africa in the Egyptian “Tale of the Shipwrecked Sailor” by Amenaa (of the Middle Kingdom [= ca. 2055-1650 BCE]).

Another folkloric source is the migration/origin-myths already alluded to. Well known in the west are the Celtic immrama (= voyage-tales) well proven in Ireland but even more famous are the Viking/Norse sagas. In both cases, the sea predominates in what are classified as “Land Beyond” tales. Their frequency and number puts into perspective the oft-put question, where are the African Lands Beyond equivalents?

Going north of Mali lies another piece of desert as long as the 1000-mile extent seen further south as the Namib Desert and they are the western fringes of the Sahara Desert. The western Sahara is also the western end of the Magreb or north Africa west of Egypt (= Tunisia/Libya/Algeria/Morocco/Mauritania). Ports of northern coasts are said by no less than an Africa-centred/Afrocentric than Chancellor Williams (The Destruction of Black Civilisation 1984 & 2002) to have been of little concern/interest to Saharan Blacks or other Africans.

Resources: Finances

Factors to be observed is just how matters African have been treated even in the near past, as emerges from various works by such as Basil Davidson, George Murdoch and others. When Asia plus Europe are been dealt with, the tendency is for individual countries to be discussed. The second largest of the continents of the world is Africa. By far the most famous of any part of the continent Africa is Egypt. A past tendency of writers noted by Davidson plus others has to been the detaching of Egypt from the rest of Africa and having done so successfully in their opinion, we then have Egypt plus the Magreb and then Africa.

More refinement of this is of a further division of non-Egyptian Africa into the Magreb (north Africa west of Egypt) and Sub-Saharan/Black Africa. This gives an absurd partition of Africa into Egypt, the Magreb plus Black Africa the even dafter notion that all are quite separate. This and the fact of so much of the past of the rest of Africa being revealed by archaeologists with spade and trowel not by historians using written documents, we come to the much-cited Murdockian comment already noted leading to more contrast of Egypt and the rest of Africa but this time, west Africa. Namely that for every ton of earth excavated on the Nile, a teaspoonful is moved on the Niger.

Something that may make comparison not a contrast between west Africa and Egypt possible revolves around use of gold. The amount of goldwork found among the grave-goods found in the tomb of the Egyptian Pharoah called Tutankhamun is well known. What is not nearly so well known is that to judge from the descriptions by Islamic historians, an intact grave of a Malian Emperor (if ever found) would reveal something of a west African analogy for the tomb of the Egyptian Pharoah.

Non-African interest in west African gold goes far back into antiquity to judge from the earliest records we have but they are scanty indeed. The earliest apparently relate to the commercial activities of the Phoenicians in their Lebanon homeland plus their colonial descendants at Carthage (= Poenis/Punis in Latin [close to Tunis]), Gdr/Gadir (= Gades in Lat. = Cadiz, Spain), Lixos (in south Morocco).

Unfortunately, very little has survived in the homeland or in the Punic or western colonies of this Phoenico/Punic literature that those expert in studying such matters state was vast. This means that what does still exist comes down to us from mainly non-Phoenico/Punic sources. It does appear that at somewhere around ca. 600 BCE. A number of Phoenico/Punic attempts at rounding Africa were made. One was that sent by Pharoah Necho II (= the Necos of Herodotus) that prompts a brief note by Herodotus to mainly dismiss it. The Phoenicians settled at Carthage sent Himilco to explore the west coast of Europe but the only really substantial account to survive is that in Ora Maritima (= Sea Coasts) but is scant and what there is the subject of being altered to the needs of Late Latin poetry nearly 1000 years later by Rufus Avienus.

Of probably around the same date as the Periploi (= Voyages) of Necho plus Himilco is the Periplus of Hanno (= Voyage of H.). This is likely to be the most complete of Phoenico/Punic Periploi that still exists but this is only because of the Greek abridgement of the original probably made at the request of Polybius (2nd c. BCE Greek). Another possible such Periplus may be what lies behind the finding of the remains of a wrecked specimen of the Phoenico/Punic vessel-type called a hippos by Greeks from its horse-headed stem plus stern. This involves yet more Greeks, in that the find was evidently made by Eudoxus. This is reported by Strabo.

Hanno may be the origin of what was written about the Phoenico/Punic traders in west Africa by Herodotus (ca. 450 BCE) and Pseudo-Scylax (so-called from his once being held to be the same as Scylax of Caryanda but of ca. 450 BCE, therefore later). Hanno does not specify gold was traded for Carthaginian goods nor does he mention that these goods involved the salt Edward Bovill (Golden Trade of the Moors 1958) says was all that the west Africans would exchange their gold for.

A later interest in west African gold came from the Romans according to Richard Jobson (The Golden Trade: or a Discovery of the River Gambra & the Golden Trade of the Aethiopians [original 1623]). Jobson (ib.) described how the arms captured from west Africans in battle included shields of gold and that these in turn were paraded as part of the triumphs general for Roman victories. This means they assumed some importance in the Roman mind. It also piqued Roman interest as to where the gold came from. Jobson further wrote that Roman efforts at finding the source were frustrated by the desert conditions of the western Sahara that caused the deaths of many of the Roman expedition.

The sources tapped by Curtius (1st c. CE Roman) would have been part of what Jobson (ib.) cited when noting these non-African participants in the west African gold-trade. Whether the Roman difficulties overland can be plausibly tied to the sea-voyage of the Roman-loving Greek named Polybius (2nd c. BCE) recorded by Pliny (1st c. CE Roman) as going down the west African coast and seemingly trying to find a maritime route remains very uncertain.

More shields were mentioned by al-Bakri (11th c.) as covered in gold were present at the court of the first known of the great imperial kingdoms of west Africa. The Ghana (= ruler/king) of the Wakor Empire is further said by al-Bakri (a Muslim from Andalusia [= southern Spain]) have had spears mixed in the same way. In “Mandinga Voyages Across the Atlantic”, Harold Lawrence (African Presence in Early America ed. Ivan Van Sertima 1992 & 1999) says spears plus lances made of an alloy of gold and silver occurred at the court of the Mansas (= rulers/kings) ruling the Malian successor to Wakor.

Other historians add to al- Bakri when reporting the amount of gold that accompanied the Ghanas and Mansas into their graves (& may explain why an intact royal grave of this type has not been found to date (after all, Egypt proves that tomb-robbers are nothing new). There are stories of nuggets of gold for tethering horses, collars of gold for dogs, etc.

If this suggests some profligacy in the use of gold because of the proximity to sources, this as nothing when we read of descriptions of the Hajj of Mansa Musa to Mecca in the online encyclopedia called Wikipedia. There we read of a procession of 60,000 men, 12,000 slaves gold bars of 4-lbs; heralds wearing silks carrying staffs of gold; 80 camels bearing loads of gold dust weighing 50 and 300 lbs according to varying sources. All were fed and watered by Musa en route; mosques were built each and every Friday. Musa donated to various cities en route and his profligacy with gold was held to have lowered the value of it in Cairo for decades afterwards.

Even allowing for exaggeration, this reign of Musa as Mansa of Mali is surely more than enough to indicate that a past Mali is not to be compared with that of the poverty-ridden state of that name today. It is against this background plus the oft-made comparison of crossings of seas of salt in the form of oceans and of sand in the form of deserts that we place the analogy of one Malian ruler attempting to cross the Atlantic and another crossing the Sahara.

Relatively few historians bother to detail west African involvement overland or overseas in these spheres. Indeed, the kind of sea-bound commerce reported by Jean Barbot was seen to have been dismissed as a mistake. The growing aridity of what was the fertile Magreb is exemplified by the Arabic term for most of the same region that is sahara simply meaning desert is held to rule out trans-Saharan trade.

Resources: Seacraft

A source to be mentioned now is “The Canoes of Oceania” by messrs Haddon and Hornell (published between 1936 & 1938). Alfred Haddon & James Hornell (ib.) argued that the earliest migrants coming east from Austronesia (= now mainly Indonesia) to the islands of Micronesia in the west Pacific went on rafts then canoes. This raft-first/canoe-next migration also seems to be repeated by Austronesians heading west across the IOR towards Madagascar to judge from what was written by Pliny and the many works by Roger Blench. Pliny (1st c. CE Roman) described rati that actually means raft but may (I?) attest twin-hulls joined by a platform. Indonesian traits like types of instrument, the disease called elephantiasis, varieties of bananas, etc, were brought by sea to west Africa.

There is also some indication that some groups from what is now India migrated to Indonesia (= Indianised Islands) at early dates and are possible among those in the west Pacific. West of India across the Indian Ocean there are small Indian mammals plus vessel-types in Madagascar. Indians on both sides of Africa would be shown by the detailed map so helpful to Europeans trying to find the source of the Nile in east Africa and the Fra Mauro (15th c. Italian) Map shows more Indians ship-borne off west Africa. The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea (1st c. CE Egypto/Greek) showed the Indian vessel-type variously called a shangadam/jangada occurs off east Africa, west Africa and on the far side of the Atlantic. A number of traits again are traced by sea from India to west Africa.

A number of periploi (= voyages) were made by Phoenicians from either the Lebanon homeland or colonies at Carthage (= Poenus/Puni [hence Punic]) plus Gadir (= Gades/Cadiz, Spain). One was by Phoenicians sent by Necho of Egypt round Africa; Carthage sent Himilco to west Europe and Hanno to west Africa (& said by Pliny to have rounded Africa); hippoi went for days from Gades to fish of Lixos (Morocco) also for days at a time and apparently sometimes as far round as east Africa to gauge from that found by Eudoxus. As these voyages all appear to have taken place at about the same time, they possibly attest some coordination. Notwithstanding, that found by Eudoxus, Strabo was quite rude about these Phoenico/ Punic hippoi when categorising the hippos as a very poor type of ship.

A large but simple type of dugout-canoe is traced between Chile and Columbia by James Hornell (Water Transport 1946). This is more or less the entire west coast of South America. Much of the rest of West-coast Americas is covered by voyages from Peru/Ecuador to west Mexico are attested by archaeological finds and early Spanish chroniclers. From Peru/Ecuador to west Mexico occurred on the balsa-log rafts also used by Thor Heyerdahl when leaving from Peru for the Tuamoto Islands, a distance of between 4000/4500 miles. More Amerinds (= Amerindians = American Indians = Native Americans) as ocean-going are the East-coast Amerinds shown by Jack Forbes (The American Discovery of Europe 2007) to be so in forms of dugout-canoe.

There is more about some of these types in other articles in other articles of this series. Absolutely salient here is the recognition that none of these ocean-going types is any whit superior to the equally ocean-going African dugout-canoe. What must be something of a surprise is that suggested turning of Africa from ocean to ocean at a time when rafts were in use do not prompt the controversy that the arguments of Africans on the ocean has.

Another ancient people put forward as seamen are the Greeks, However, the earliest Greeks were not sailors and had no word for the sea but adopted the Aegean word of thalassa (= the sea). If works by the oldest Greek poets named Hesiod plus Homer (of the 10th c. BCE on the argued-for dates of Bernal [vol. II of Black Athena 1991]), they may really attest the relevant era. Homer shows King Nestor as falling down on his knees in praise of the gods for having survived a voyage between the Aegean islands of Tenedos and Lesbos; a distance of no more than 50 miles. Bjorn Landstrom (The Ship 1961) says the famous black seacraft of the famous Catalogue of Ships in the long poem on the Trojan War by were no more or less canoes matched by those of Africa.

In the opposite or northwest corner from Aegeo/Greek parts of Europe, were the Celtic and Nordic peoples. The Celtic currach matches the west African dugout-canoe in being able to possibly land almost anywhere. Paddling of the canoes brings us to John Heywood (Dark Age Naval Power 1991 & 1996) recalling his British Army training and saying this was more effective in approaching an intended target than even muffled oars. Douglas Peck (Yucatan: Prehistory to the Great Revolt 2005) examples Diego Chanca (16th c. Spaniard) saying Carib canoes could be paddled up to 150 leagues (= 400/450) at one go. For the Vikings settled in Russia as the Rus, the sleek Viking war-ship was replaced by the Slavic dugout-canoe in which parts of the Byzantine Empire were raided from across the Black Sea.

Nor was the Viking drakarr (= dragon/war-ship) any better as sea-going vessel than the west African dugout canoe according to Michael Bradley (Dawn Voyage 1991). The re-creation of the Viking ship excavated at Gokstad (Norway) is described by Percy Blandford (The History of Small Boats 1974 ) as having a “hull that worked a lot” (= leaked badly). Whatever, the problems with canoes, the African craft as one-piece constructions were not as subject to such leaks. This is not to say that “balers” were not needed aboard canoes but Bradley (ib.) says they were incomparably superior to the Viking drakarr/longship. Bradley further wrote that west African canoes were superior to any vessel of Leif Eriksson (the first known Eur. to reach the Americas).

Reference has been made to the Periplus Maris Erythraei (= Voyage on the Erythraean Sea) and its mentioning Indian Ocean vessels. Another that it describes is the dugout-canoe that it seems to suggest was in use alongside the proto-mtepe that it calls the ploiarion. Also that commerce between what are now Mozambique and Somalia, so means virtually all of east Africa south of the Horn of Africa is covered by these vessels.

Further south are the sub-tropical waters already mentioned that are in turn off coasts that are mainly South Africa and here the population was mainly that of what we are calling the Khwe. This is an umbrella term for what are probably are otherwise a vast number of names. They are probably the oldest extant strain of humanity there is. We have also seen it is stated did not know the use of boats. This is the generally received wisdom and a particular online source saying this very categorically is the New Advent Encyclopedia.

Disagreeing with this would be Erik Holm ((Bushman’s Art 1987) but Holm is heavily criticised by John Parkington (Digging Stick 1988) on several counts. However, on the matter of Khwe boats depicted in rock-art at Siloswane (Zimbabwe) he is supported similar scenes at uKhahlamba (KwaZulu/Natal, South Africa) reported by Ndukuyakhe Ndlovu (Incorporating Indigenous of Rock-art in KwaZulu online). On the other side of South Africa are the River San or Banoko who are Khwe/San who have fished from boats on the River Okavango and apparently done so for millennia. Also the western or Atlantic side of South Africa is Robben Island most famous as the island prison of Nelson Mandela.

A rather earlier prisoner was Automashata (= the Herry of the then Dutch of what became Cape Town). He was a Khwe and one of the very few escapees from Robben Island. His escape was made in a rowing-boat of an extremely dilapidated state but got it across the sea to the mainland. This seems to have astonished his Dutch captors and again may hint at an expertise that would otherwise be unknown.

The Black neighbours of the Khwe over most of southern Africa are mainly speakers of what \are called Niger/Congo (= N/C) languages. The N/C-speakers were the ancestors to the Bantu who are the black neighbours mentioned came as growers of yams plus palm-nuts not cereals according to messrs. Diamond (Discover Magazine 1994 & online) and Lacroix (Africa in Antiquity 1998), etc.

Skeletons were found at Bambandyanalo (South Africa), Mapungubwe (South Africa), etc, that had Khwe and Bantoid affinities. They are discussed in “A fragmentary skull cranium & dated Late Stone Age assemblage from Lukenya Hill, Kenya) by messrs. Gramley & Rightmire (Man 1973); in “Expansion of Bantu-speakers vs. development of Bantu in situ” by Richard Gramley (South African Archaeological Bulletin 1978); Felix Chami (The Unity of Ancient African History 2007) plus others.

To this is added the thought that the clicks of Khwe-group languages are an archaic speech feature but are felt to originate in reduced Bantu prefixes by Graham Campbell-Dunn (Maori: the African Evidence 2007). This amounts to a small but growing number of authorities telling us that the Proto-Bantu were probably in parts of southern Africa millennia before they were supposed to be on the received wisdom and accords with certain European maps.

These maps are cited in “African Floods, Lakes & Random Matters” (online). They are also cited by such as messrs. Hall & Neal (The Ancient Ruins of Rhodesia 1902), Cooke Human migration from the rock-art of Rhodesia [Africa 1965]), etc. Among those being cited are messrs. Sanudo/Sanuto (13th /14th c. Italian), Vesconte (13th/14th c. Italian), Mauro 15th c. Italian), Barbosa (15th c. Portuguese), Santos (16th c. Portuguese), Johnstone (16th c. English), etc.

The Sanuto/Vesconte Maps bring something of a surprise. They appear to position Robben Island in near-perfect relationship to the mainland of western South Africa. It is surely legitimate to wonder at how this knowledge reached the outside world? Given the arguments set forward in “Africans, The Sea & Some Parallels” about other small African islands, this would appear to have been Africans. The most singular feature of the mainland adjacent to Robben Island is probably Table Mountain overlooking the harbour plus the rest of the Bay/Cape districts of Cape Town (South Africa).

The earliest Portuguese name we have for the Bay/Cape is Cabo da Tormentosa (= Cape of Storms) later renamed as Cabo da Boa Esperanca (= Cape of Good Hope). Luis de Camoes (16th c. Portuguese) personalised the ferocious dangers the Cape as Adamastor. This figure is held to originally have been a minor member of the giants of Greek myth called the Titans. Camoes has it that Adamastor was in love and having arranged a tryst, she tricked him and the giant was turned into a rock.

Nor is this the only example of the name of a giant applied to Table Mountain. Another is Umlindi Wemingizimu (= Watcher of the South). He too was turned to stone but this time the female was a goddess. The name is purely Bantu but a difficulty is that the Bantu are generally alleged not to have reached Cape Town till the 1850s. However, we have seen there are European writers indicating something very different. The most important feature seems to have been the Bantu-ruled Mwenemutapa/Mwenemetepe (= Monomatapa) Empire being shown to have stretched down to the Bay/ Cape region long before ca. 1850.

There is something here that repeats a pattern frequently seen inside the Classical world of the Greeks plus Romans. These Greco/Roman or Classical writers tended to give Greek or Roman names to non-Classical deities that were often from outside Europe. Given this background, Umlindi becoming Adamastor is surely no great surprise. What this further indicates is that the most probable source of the above-seen information reaching European mapmakers was Africans. Nor can it seriously be doubted that west Africans went to sea, especially given that Umlindi is apparently invoked in the role of tutelary guardian by sea-going Bantu off western South Africa that is matched by several deities to the north in west Africa.

Realisation that there was something attracting non-African attention to the Cape/Bay region of western South Africa in decidedly Pre-Colonial days is reinforced by echoes of what happened at those dates in early contact times. A good example of non-Africans wanting to barter with west Africa in antiquity being so echoed comes with what in sum forms the title of “Portuguese adaptation to trade patterns Guinea to Angola (1443-1640)” by Eugenia Herbert (African Studies Review 1974). Likewise, simple vessels landing on the Atlantic shores of Africa in the past coupled with groups pushed to the coast taking up the seafaring of those they have now absorbed or replaced bring us to those that Germans when what for them was Sudwest Afrika.

It quickly becomes apparent that there was little love for the Africans under their administration by the Germans in their brief tenure of Sudwest Afrika/Southwest Africa. This is plainly shown by the massacre of the Herreros in Sudwest Afrika or Namibia. Having cleared extensive areas of pesky Africans, land was now available for colonists. Ships bringing would-be colonists did not have a jetty to sit alongside when landing such valuable cargo. This is shown by a Wikipedia author at Swakopmund (Namibia). Here was also seen some of the extremely dangerous swell helping to name the Skeleton Coast and yet the ship-to-shore landings of colonists was in the pre-jetty hands of Africans. They did so in canoes fully matched to as far north as Guinea in Atlantic-west Africa.

Analogous to this kind of extent would evidently be a formative element of the related from which emerged such as the Ijo (of Nigeria) according to the Ijo Genesis (online). Reclus (ib.) refers to what is presumably originally from a Portuguese report saying their colonists on Sao Tome were harassed by wrecked Angolans. In the light of what is being said in these pages, it seems legitimate to wonder if these Angolans were rather more part of the canoe-based movement being described here. If so, this would mean Angolans were there on their own volition not just as wrecked crews and this too fits with the Angolans also recorded as sea-based fishermen.

It remains very uncertain just how ancient the “ancient” copper-sources of western South Africa plus Namibia actually are. However, to the matter of possible seafarers among the inhabitants of southern Africa we can add that there was very early movement of copper around parts of Africa for millennia is plainly shown in “Red Gold of Africa” by Eugenia Herbert (1984).

That some of this was moved by sea emerges from a variety of sources. The kind of political unity envisaged by Leo Frobenius (The Voice of Africa 1913) seems unlikely. However, he does make the case for a possible coastal entity that differs from groups inland on several counts stretching from at least Angola to Morocco and this would reflect something reported by Jean Barbot (as Hair, Jones & Law ib.).

If copper from afield as South Africa, Namibia up to Congo was moved by sea, it was probably in the hands of Bantu of further north (esp. Gabon). Cases were seen above to attest the taking up of pre-existent traits and another may have been that of the Pre-Mahongwe and Mahongwe/Mpongwe in part of Gabon, to judge from what will be said about commerce. Here too the age-old building of canoes led to some proud builders of canoes.

At a time when European attribution of anything positive to Africans was somewhat rare to say the least, a British captain of the Royal Navy named Thomas Boteler (Narrative of a Voyage to Africa & Arabia 1838) could write Mahongwe canoes were built for “strength, symmetry & solidity”. This praise was followed by Richard Burton (Two Months in Gorilla Land & the Cataracts of the Congo 1876). Burton (ib.) further wrote that he thought the strength of Mahongwe canoes would have been capable of taking crews almost to the Americas.

Authorities dismissing west Africans being capable of sea-bound commerce were cited above were cited in the first section of this article. According to messrs. Markwat (as Herbert ib.), Fage (Cambridge History of Africa 1975), Patterson (The North Gabon Coast 1975), Herbert (1974 ib.; The Red Gold of Africa 1984) plus others are of a decidedly different opinion. They not only allow that the commerce actually took place but also that the foodstuff reported by Barbot as taken on long sea-journeys by Africans was the well-known biscuit-like kankey widespread in west Africa. Burton (ib.) adds that Mahongwe canoes could carry 10/15 tons; John Fage (ib.) says they carried up to 100 people; Robert Smith (JAH 1970) says that such canoes returning home would go against prevailing currents.

West Africans traded and fished at sea from the southwest to the shores of Africa facing that part of the Atlantic called the Gulf of Guinea. These sea-based economies are underlined by the Greek-coined term of Ichthyophagi (= Fish-eaters) for such African groups. The dangerous swell of parts of the Gulf-facing west Africa was also to prompt use of Africans and their canoes on ship-to-shore duties. Carl Christian Reindorf (a History of the Gold Coast & Asante 1896) shows persistent tradition of canoe-borne migrations the length of the Gulf of Guinea.

The Guinea swell was again thought to be too dangerous for Europeans trying to land on the coast of Ghana (= Gold Coast), so yet again west Africans and their canoes were used to ferry Europeans to land. The type of dugout-canoe used for this purpose by the Germans far to the south in Namibia were those of the speakers Krio/Kru languages now mainly of Liberia.

For Lacroix (ib.), from the Krio came the pilots-cum-translators replacing the Lixitae that are described as having been used in this capacity by Hanno. The Krio/Kru were accomplished maritime fishermen, as shown by Hornell (ib.) when reporting the enormous fish landed by Krio fishermen in their canoes and Elizabeth Tonkin (in Stone ib.) notes that that “Fishmen” still applies to a section of the Krio.

A dugout-canoe of the Krio type was renamed by Hannes Lindemann (Alone At Sea 1958) as Liberia II. It was of the 1/2-man standard for Krio fishermen and was taken successfully across the Atlantic by Lindemann (ib.). This was not only of the especially archaic dugout class but also he ate mainly the all-fish diet caught en route already seen to have led to the ancient term of Ichthyophagi.

The age-old fishing economies under the Ichthyophagi label on the Nile are recorded by Herodotus (5th c. BCE Greek). The Nile is also the source of the Pre-Dynastic scene depicted on the Narmer Palette and is that of the first recorded water-borne battle according Flinders Petrie (The Making of Egypt). Whatever the arguments of whether ancient Egyptians were black, it is important to emphasise that the Nile is an African not just an Egyptian river. This is also to observe that what applies to the Palette is equally the case with wall-art at Tomb 101 Hierankopolis (= Nekhen, Egypt). The most famous battle of the ancient Nile is the Battle of the Nile Delta where Merneptah of the 19th Dynasty defeated the Sea-Peoples

This may mean that the Nekhen plus Narmer river-battles were as likely to have been in Kush/Nubia as anywhere in south Egypt. The repute of Kushite Nile fleets is nicely shown by invitation from a king of the 15th or Hyksos Dynasty to Kush to send its fleet against the native rulers of Egypt. There are also the massive 18th Dynasty forts near Nekhen clearly built to contain the threat of the Kushite navy. More riverine fleets are those of other Africans seen on the Niger on the opposite side of Africa during the period of the great imperial sequence of west Africa.

The Niger also figured in the fleet of canoes bringing Mansa Musa plus family back to the Malian capital at Niani on return from their Hajj. Warfare on rivers also takes us to the Niger when we read of Sonni Ali blocking the retreat of his enemies during the siege of Timbuctoo (Mali) using 400 canoes. Harold Lawrence (in African Presence in Early America ed. Van Sertima 1992 & 1996) also notes the 3000 canoes used by Askia Ishaq to evacuate Gao in the face of Moroccan invaders. Large numbers of these vessels were recorded as engaged in sea-based fishing by west Africans from Congo to at least Guinea.

Africans from Senegal were said by Luis Feijo (19th c. Bishop of the Cape Verde Islands) to have reached the Cape Verdes. They were fishermen and another Portuguese is Pacheco Periera who is cited by Bradley (ib.) saying west Africans were seen as fishing up to ca. 100 leagues out to sea and coincides with the distance of 300/350 miles from Senegal to the Cape Verdes. Other canoes reaching these islands are those reported to Christopher Columbus as having left for points west that means only the open Atlantic and the Americas in front of them.

Such African sea-craft on the Atlantic would probably qualify for the label of small ships used by Clinton Edwards (when discussing Amerind sea-going vessels). The comment above to have been written by Richard Burton (ib.) was that Mahongwe canoes could have made it to the Americas. Water-tank tests by Michael Bradley (Dawn Voyage: The African Discovery of America 1991) do much to attest the seaworthiness of west African canoes. The more practical side of this seems to be provided by what was said by Hannes Lindemann (ib.) on a voyage we saw paralleled standard west African practices on several counts.

Lawrence (ib.) is one those noting certain Amerind traditions again reported by Columbus. This was that black traders were in islands off the East-coast Americas. These were the islands of what we now describe as the Caribbean Sea on the far side of the Atlantic Ocean from the west coast of Africa.

Lands Beyond

For such early Greek authors as Hesiod and Homer (10th/9th c. BCE on Bernal’s dating) appear to have known little more about Atlantic-facing geography than that there was a shoreline surrounded by what they called Okeanos (The Ocean). Even by the time of Herodotus (ca.450 BCE), he could not name a Magrebi ethnia west of the “Pillar of the Sky” identified with the highest point of the Hoggar/Ahoggar Mountains by Livio Stecchini (“Sahara” online). However, native tradition drawn on by such Islamic historians as al-Masudi (10th c. Syrian) and Abd al-Sabd (Malian of mainly the 17th c.) does allow for movement across the Magreb/Sahara.

Traders crossing the desert would be underlined by Abd al-Sabd (author of the Tarikh es-Sudan [= History of the Sudan]) saying Mali sent priests to help the Egyptian Pharoah in his contests of magic with Moses. Al-Maqrizi (14th/15th c. Egyptian) that “Nubians went to the left (= east) & the Kushites to the right (= west)” Both Herodotus and al-Masudi have enough in common in their combining history and geography for Masudi to have the title of the Islamic/Arabic Herodotus; accounts of Pyramids associated with water; Pharoahs bent on conquest outside Egypt. The difference about the two is that the Pharoah of Herodotus was active in Europe, whereas that of Masudi was in action in Africa to the far west.

This tells for west/east plus east/west but most records attest north/south or south/north. So too may the chariot-trails first brought to our attention mainly by Henri Lhote. The eastern trails are mapped by messrs. Oliver & Fage (A Short History of Africa 1990) as roughly Phazania (= the Fezzan, Libya) to near Timbuktu. Western trails approximate to near the foothills of the Atlas Mountains to again close to Timbuktu/Timbuctoo (Mali) on the River Niger.

Tunisia/Libya does not just contain most of the eastern chariot-trails but also the territory of the Nasamones. Charles Meek (Journal of African History = JAH 1960) seemed to think Nasamones incorporates a version of the Egyptian Nahasy (= Blacks) plus the Amon/Ammon that is also common in African personal and ethnic names. Herodotus records a few Nasamones as having gone south of the Sahara and it seems they may have provided the guides that Diodorus Siculus says led the party of Alexander to the Siwa (Eg.) shrine. The Nasamones were the neighbours of the Garamantes and shared ancestry with them. Rather further afield is covered by the comparison made by Pausanias of Nasamones and the Atarantes on the far side of the Magreb in Dyris/Atlas.

Garama was the ancestor of the Garamantes and Nasamon (son of Garama) was the ancestor of the Nasamones. On the far side of the Garamantes were the Gaituli. Some of the towns said to have been taken by the Romans from the Garamantes were held to have been as likely to have been Gaitulian as Garamantian by Robin Law (JAH1967). The article by Law bears the title of “The Garamantes & Trans-Saharan Enterprise in Classical Times”. Garamantian pottery has been found in lower levels at Timbuktu (Mali); they may have been a formative component of the Mande-speaking Soninke for Frobenius (ib.); a Garamantian king is recorded in action south of the Sahara; if Garian/Carian is a shortened form of Garamantes, this may be seen as part of Teichon Karikon (= Fort of the Carians?) for Stecchini (ib.).

Henry Parker (JRAI 1923) tied the term of Wa nGara (= Children of Gara) to the obsolete Sudanic (= Saharan [not Sudanese]) term of Wangara (= the Mande) taking us in turn to the name of the Gara-mande/mante. Parker (ib.) is also one of those holding that words from the vast Mande-speaking world can render the Garamantian placenames in Latin in the Plinian list. Parker listed Mande Barakunda (= Boat-town) as Latin Baracum; Mande Lasikunda (= Closed market) as Latin Alasi; Mande Tabusakunda (= Market under the Tabu tree [from Tabu = Fig]) as Latin Tabusa. Rounding this off nicely is Henry Lhote (as Meek ib.) looking to the Mande-group language of Soninke to regard Soninke Da Isa Bari (= River of the Great God [= the Niger]) as Plinian Dasibari.

Parker’s translations of Mande words hidden in the Latin of the Plinian list bring to mind just how many times markets figure in the town-names that may be as much Gaitulian as Garamantian. This seems to accord with the title showing the Garamantes engaged in “Trans-Saharan Enterprise” that as seen, may have taken them to as far west as Teichon Karikon on the far side of the Magreb/Sahara. Wangara is also not just an obsolete term for the Mande but also fits with Wangara marking the Mande as traders as Dyula does. Moreover, this fits with the Mande as among the Aithiopians and Garamantes put among the Aithiopians too by Ptolemy. Further is Garamantes described in Latin in words meaning very dark/very black, thus perusti for Solinus and Lucan; furvi for Arnobius; niger for an author in the Anthologia Latina.

If Wakor is another variant of Wangara, there is Andreas Massing (The Wangara: An Old Soninke Diaspora in West Africa online) saying Wakor/Wakore were seen as white/light-skinned (= Berbers?). He cites such Islamic writers as Idrissi, al-Bekri, etc, saying this but that the Tarikhs (= Histories) classified them as black or dark-skinned. Again Wakor and Guangara seen as variants of Wangara lead us to more confusion when we have seen al-Bekri/Bakri described the Wakor as light-skinned but the Guangara as black/dark-skinned.

What seems to be at work here is shown in the “Geographia” by Ptolemy (2nd c. CE Egypto/Greek) and “What Happened to the Ancient Libyans: Chasing Sources Across the Sahara from Herodotus to Ibn Khaldun online). Ptolemy wrote of Leukaithiopes (= White Africans) plus Melanogetuli (= Black Gaituli). Smith (ib.) wrote that the Berbers are said by ibn Hawkal to have consisted of 22 Banu Tanamak (= Black) plus 19 Sanhaja clans. This very clearly attests that Berberisation then cultural Arabisation of the Magreb was a very slow process that continued till at least the time of ibn Hawkal.

Ptolemy using such as Leukaithiopes plus Melanogetuli still remains curious. According to Gaituli/Getuli probably means “From the South” and from the south in Africa still tends to mean from Sub-Saharan/Black Africa. A parallel is called to our attention by Clyde Winters (Atlantis in Mexico 2005) n s w (= n y swt = Man from the South in Egyptian script) that denoted someone from Kush themselves among those that the Greeks called Aithiopes. The latter is from an interesting Greek compound of aithios (= burnt) plus opes (= face) giving Aithiopes (= Burnt-faces = Black Africans). Another parallel with Egypt is Phoenicia called Djahi in Old-Egyptian and Senegal called Djahi in the Wolof language of Senegal and that Djahi means “Place of Navigation” according to Cheikh Anta Diop (The African Origin of Civilisation 1984).

The Wolofs once ruled an area that became known as the Ganar/Gannar Coast. The name occurs in Ganaria extremis (= Cape Ganaria = ex-Cap Blanc = Ras Nouidibh), the Canary Islands, the Canari people of the Dyris/Atlas region. In “West Africa & Ancient Navigation” (online), the case for separating these placenames and the Latin canes (= dogs) is made. The more so given that the Wolof name of N’Dar applies to what the French called St. Louis. The Dar/Dra part applies to river-names bracketing the Ganar Coast. The southern Dar/Dra is the Senegal and the northern Dar/Dra is the Wadi/Oued Draa (Morocco). Otherwise the Oued/River Draa is frequently identified with the River Lixos mentioned by Hanno.

Michael Skupin (The Carthaginian Columbus online) is one of those holding that the River Lixos was a river of “Aithiopia/Aethiopia” (approx. Sub-Saharan/Black Africa) not of “Libya” (= roughly the Gk. for most of nth. Africa). This should apply equally to the inhabitants of the banks of the river called the Lixitae. Their importance is that they provided Hanno with his first interpreters and being able to converse with west Africans to probably as far south as Liberia (as Lacroix ib.). In turn, it can be assumed this means they were navigators to Hanno over the same distance.

Yet another oddity comes from the description of inhabitants of what has been called the Dyris/Atlas region. Dyris seemingly relates to Greek douros and Atlas to atlao and both have the general meaning to suffer, endure, hard to bear, etc. This would accord with the description of the Dyris-folk called Atarantes constantly complained the sun burnt face plus skin. This would also seemingly qualify them for the Greek label of Aithiopes seen to mean Burnt-faces and yet Herodotus does not appear to call them Aithiopes. When it is realised that it was the Dyris-folk called the Atlantes that cursed the sun for burning skins and faces for Pliny and Pomponius Mela (as Stecchini ib.). This has prompted Smith, Skupin, Stecchini plus many others to wonder why Herodotus treated the Atrantes/Atarantes and Atlantes/Atalantes as separate. Stecchini suggests the name of the name of the Atlantes became mixed up with the Berber placename of Adrar widespread across the Sahara.

Even if Herodotus does not describe the inhabitants of the Dyris/Atlas region as Aithiopians/Blacks, Strabo plus other Greeks do. This should apply equally to that most famous of those inhabitants, Atlas himself. In other of my papers, the original of Atlas is shown as one of several ascetic figures climbing into the High Atlas for meditative and spiritual reasons. A very early description of Atlas is by Homer (10th /9th cs. BCE?). He describes Atlas as a master-mariner and as knowing the depths of the sea. This brings us to a story told by al-Umari/Omari (14th c. Syrian). He retails an account of fleets sent by the Malian Empire “to seek the far side of the ocean”. Of the first fleet, only one vessel returned. From the description of the “undersea stream”, not only are the “deeps of the sea” known but seems to indicate a point where the Canarian Current turns into that called the North Equatorial and the captain getting back to his home port shows he too was a master-pilot.

Giving more substance are the many comparisons of this “Returned Captain”. One of them is with the Egyptian story of “The Shipwrecked Sailor”. Among them are that they concern (a) parts of Africa; (b) voyages from their respective parts of Africa; (c) both being long-distance voyages; (d) both were sponsored by their respective rulers; (e) both concerning returnees; (f) being told to their respective rulers; (g) both coming from Egyptian sources (Amenaa being our source of “Sailor” & the Governor of Cairo being who told Umari re. the Malian fleet); (h) both the Sailor and the Captain remaining unnamed; (i) frequency of the voyages; (j) serious problems encountered despite that frequency; (k) single survivors (the lone Egyptian sailor & the single ship of the Malian Captain), (l) both seemingly folkloric.

The Shipwrecked Sailor is known to be largely folkloric but features regularly in serious maritime histories. This being so, there seems to be no valid reason why this does not equally apply to what has been called here “the Returned Captain” seen to share so many points with “The Story of the Shipwrecked Sailor”. Nor need this be only such Egyptian resemblance for west African voyagers. Conditions on the Nile make it an ideal candidate for a place where sails evolved. There does not appear to have been a lot of early Nile craft and those ocean-going on the Indian Ocean described by Eratosthenes (3rd c. BCE Egypto/Greek). Somewhat similar may be the barge-like vessel taken by Thor Heyerdahl (The Ra Voyages 1971).

Sails of Atlantic-facing Europe have long been queried, as the material of those of the Celts or Gauls of Atlantic-west Gaul/France of leather prompted Julius Caesar (1st c. BCE Roman) to ask if this is due to their not knowing fabric. East-coast Amerinds and west Africans also had sails of varying materials but in each case, these sails are attributed to Iberian sources (Spanish for the Amerind sails & Portuguese for west African sails). The Amerind sails are effectively discussed by Jack Forbes (The American Discovery of Europe 2007).

The wide variety of cloths in west Africa makes it unlikely that the material for west African sails came from where cloth-making was unknown. The square shape plus reed-matting of west African sails and an evolution said to be due to allowing winds to blow through so allowing less wear of the sails must tell for native sources. The differences plus that of rigging from those of any part of Europe in form plus material are surely too radical to make a Portuguese origin very likely.

This is equally so for the long-distance trading of west Africa. It will now be obvious why so much attention has been paid above to trans-Saharan movement and the commerce that seemingly was part of it. This is that west Africans went to considerable efforts to encourage such long-distance trade. A superb example of what is at work here is provided by the location of the trade-site of Elmina (Ghana). This is held to attest Portuguese acumen but what then does this say of the fact that the Muslim Mande were trading there long before the Portuguese got to any part of west Africa, let alone having reached the stage of founding even small colonies?

The long distances between west Africa and the Caribbean plus the east coast of the Americas and the Columbus comment about are oft-quoted as ruling out west Africans ever reaching East-coast Americas. The un-seaworthy canoes of west Africa might be further cited as a factor yet that even the simplest type of the west African canoe was seen above as capable of successfully crossing the ocean.

Something else will now be become immediately obvious, namely the long description of where even the simplest west African dugout-canoe may fit in terms of sea/ocean-going vessels. This is especially true given what is said by Bradley about how elaborate west African canoe-based vessels could be (so parallels what is said on this by messrs Edwards, Peck, Forbes, etc, about Amerind sea-going vessels).

The strenuous efforts made to undertake this long-distance commerce across the sea of sand can be expected to be analogous to that across the sea of salt. The distances were not sufficient to prevent the voyage of Lindemann (ib.) in a simple type of dugout-canoe. Parallel to the dates suggested for the earliest trans-desert trade is evidence for voyages at sea. These include those going directly from allowed for by Serge Plaza et al (Joining the Pillars of Hercules: mtDNA shows multidirectional gene flow in the West Mediterranean online) as going from Guinea to Iberia bypassing Morocco en route. The argument for the crossings of the Atlantic Ocean is made in “West Africa & the Sea in Antiquity” (online).

Voyages direct from Guinea in west Africa to Iberia would be the equal of many of the shorter routes across the Atlantic and have an apt parallel in those reported by no less than Columbus. The Columbus comment about the distances between the west Africa and the Caribbean so frequently quoted by so many Afrocentrics also usually ignores some of the other points mentioned by Columbus.

The point already raised above about west African canoes unable to reach the Cape Verde Islands is not only countered by what we saw was cited by Feijo but also by Columbus. That by Columbus was to the effect that canoes were leaving the Cape Verdes westwards, so had only the open Atlantic, the Caribbean islands plus East-coast Americas in front of them. What is not to be overlooked is that west African canoe-builders were in the islands from whence we have just seen canoes laden with goods were sailing towards the Caribbean.

Columbus writing about distance ruling out an African West-coast/American East-coast connection because of distance is frequently referred to. What is rarely mentioned by the critics of Afrocentric/Africa-centred views is that Christopher Columbus also said that blacks were also trading on the far side of the Atlantic in the Caribbean. There were few greater sceptics about anyone from any part of the Old-World as Pre-Columbian sailors on the Atlantic than Samuel Morrison in “The Caribbean as Columbus saw it” (co-authored with Mauricio Obregon 1964) and yet he too allowed for Columbus having shown this trans-Atlantic trading by west Africans.

Not usually associated with this is the exchange of substances that plainly include narcotics. Metallurgy, transfer of plants, shared rites (?), shaft-tombs, tomb-finds, pottery, its technology, costume, design motifs, ethnography, other traits, etc, link Peru/Ecuador with west Mexico. This would appear to have begun as far back as 5000/3000 BCE but with an emphasis on ca. 500 BCE/1500 CE on routes of nearly 2500 miles, occurred on rafts and involved trips going against prevailing currents.

The finding of New-World narcotic drugs in Egyptian mummies is well known but not so well known is the finding of Old-World drugs in Peruvian mummies. Messrs Sorenson & Raish (Pre-Columbian Contact with the Americas across the Oceans 1996) point up writers looking for Chinese seeking American drugs. This gives distances of 5000/6000 miles of ocean and whilst this remains uncertain, the notion of narcotics sought over vast distances remains.

It is known that Egyptians went on long voyages to somewhere called Punt and there is more than a little suspicion that plants with narcotic properties were part of this. This plus the fact of bilbils of poppy-head shape and contents of opium being the most common Cypriote find in 18th/19th Dynasty Egypt supports this. So too does narcotic plants transported from Punt (= north Somalia) to Egypt plus from west Mexico to Ecuador/Peru.

This all makes notions of ancient drugs over long sea-routes less of a problem and here we come to the career of Jaime Ferrer (15th/16th c. Spaniard). He had dealings with the “Ethiopians of the Equinoctial Regions” according to Ivan Van Sertima (1976). Anyone who has read the travel journals of Baron Humboldt will know that for early Europeans, the Equinoctial Regions were Central and South America. His buying drugs and jewels from Ethiopians (= Africans) in the Americas were part of what led to his being the expert for Spain in the negotiations leading up to the Treaty of Tordesillas (1494) just two years after the first voyage by Columbus across the Atlantic.

Cloth seems to have functioned money-like in parts of west Africa according to Harold Lawrence (African Presence in Early America ed. Ivan Van Sertima 1992 & 1997). Lawrence (ib.) further cites al-Umari saying other items were used during trading but that their value was always in terms of the cloth. He also shows cloth used in strips in much the manner that we now use strips of paper that we call cheques and banknotes. Also besides cloth worn as garments in west African manner in parts of what today is called Latin America plus the islands of the Caribbean Sea, cloth again functioned took on the role of currency.

The garments referred to particularly attest what in west Africa is called almaizor (& other spellings). Lawrence (ib.) tells us that almaizor was worn in Guinea plus the Senegambia and Mali areas of the Malian Empire. Words in the Mande language of the Malian Empire include masiti/masiri/masirili used for breech-clothes, loin-cloths, shawls, etc. Having already seen that fabric in the form of garments can be seen in regions hundreds of miles apart, it will be no great surprise that almaizor seen in the form of clothes identical to those of west Africa appear as exports in Morocco, Iberia and Mexico.

Underlining this would be Lawrence (ib.) saying Mande masiti became Mexican maxtli with the same range of functions and cites no less than Christopher Columbus, Ferdinand Columbus (son of C.), Hernan Cortes (Span. Conqueror of Mex.), etc, on the matter of Guinea-cloth/almaizor having been exported to Morocco, Iberia (=Spain & Portugal) plus Mexico. Even more to the mark is the comment by messrs. Morrison & Obregon (The Caribbean as Columbus Saw it 1964) that this means west Africans were trading around the back of the world”. The point is that anyone who has read Samuel Morrison’s two-volumed “European Discovery of America” (1974 & 1994), will know of his scepticism and yet there is this comment of Africans as traders around the back of the world (whatever that means).

Bringing together movement to the eastwards from west Africa and westwards from west Africa is the parasite called Tunga penetrans, more colloquially known as jiggers, chiggers, nigua, etc. It seems that it affected people on Hajj according to the accounts given by messrs. Sorenson & Johannessen (Scientific Evidence for Pre-Columbian Transoceanic Voyages to & from the Americas Part III online). Its name indicates that it penetrates human feet and can be crippling. How it affects the movement westwards is that the Hajj towards Egypt and Arabia was that of Mansa Musa in 1324.

The chigger is of American origin and it must have great significance that it not only attests movement across the seas but seems to have affected movement across the sands. Moreover, this stands very close to both the dates for the argued-for Malian crossings of the Atlantic and the Malian Emperor crossing the Sahara on his Hajj. This means across the Atlantic and across the Sahara. The resources needed for the expeditions across the Atlantic may be confirmed by those expended on the Mansa Musa Hajj across the Sahara. This of course primarily means a precious metal that Lawrence, Van Sertima (Early America Revisited 1998), etc, consider was severally named kane, kani, kanie, kanine, kanne, gana, etc in various west African tongues. A related term is that of guanin that apparently indicates either an alloy of precious metals and/or items tipped with these materials.

Gold valued for its intrinsic value and/or its colour is known the world over and as marking kings in nearly all parts of the globe. The Before Adam series of books by Catherine Acholonu plus Lawrence (ib.) refer to orucha-nkume (= precious stone/metal) and guanin in the Igbo and Mande languages respectively. Both appear to represent alloys akin to the orichalcum that Plato (5th c. BCE Greek) evidently saw as a metal of Atlantis and sounds very like guanin.

With Atlantis being no more than a myth, it will be immediately obvious any linkage of west Africa and parts of East-coast Americas was very direct. Guanin in Africa in its most described form was of 18 parts gold, six of silver and eight of copper. Having seen that weapons of gold and/or attest people of status or honour in the Old World, it is no great surprise that Columbus as the honoured guest of Amerinds in the Caribbean was presented with spearheads to mark his presence there. Columbus sent them back to Spain for analyses that proved the spearheads were of the guanin content identical to that of west Africa.

Given that Columbus shows west African vessels were seen to be heading from west Africa towards the Americas and that blacks in the Caribbean islands were the source of the gift given to Columbus, this should be no great surprise. Two of them that had died in the islands may explain skeletons found at St John’s Bay (U.S. Virgin Islands). Uncertainty about them apparently rest on the general belief that no Pre-Columbian African ever went across the Atlantic plus the more specific doubts about any dates having been affected by sea-water.

On the other hand, claims the revealed dentition seemingly belongs to a context in which the owner of slaves would discourage any retention of the culture of the slave(s). Reference to thousands of miles away, a fox-fur armband was seriously held to identify a specimen of what in north Europe are called bog-bodies as a Celtic priest named Lovernios (see the Druid Prince 1991). Among the St John’s Bay finds was another armband but this time of an Amerind type that antedates ca. 1250 CE, so would be decidedly Pre-Columbian.

The more so in the light that Lawrence (ib.), Van Sertima (ib.) plus others have traced several placenames that seemingly attest a strong west African presence in the Caribbean plus Mesoamerica. To Yemoja (Nigeria) possibly echoed as Yemoye (an Amerind name for Jamaica) is added such as Mali, Mandinga, Ghana, Caracole, Barbacoas-Berbice, etc. All are places in west Africa matched in East-coast Americas in or facing mainly the Caribbean.

Harry Bourne (Rewritten 2011)

Akufo-Addo commissions Phase II of Kaleo solar power plant

Akufo-Addo commissions Phase II of Kaleo solar power plant

NDC panics over Bawumia’s visit to Pope Francis

NDC panics over Bawumia’s visit to Pope Francis

EC blasts Mahama over “false” claims on recruitment of Returning Officers

EC blasts Mahama over “false” claims on recruitment of Returning Officers

Lands Minister gives ultimatum to Future Global Resources to revamp Prestea/Bogo...

Lands Minister gives ultimatum to Future Global Resources to revamp Prestea/Bogo...

Wa Naa appeals to Akufo-Addo to audit state lands in Wa

Wa Naa appeals to Akufo-Addo to audit state lands in Wa

Prof Opoku-Agyemang misunderstood Bawumia’s ‘driver mate’ analogy – Miracles Abo...

Prof Opoku-Agyemang misunderstood Bawumia’s ‘driver mate’ analogy – Miracles Abo...

EU confident Ghana will not sign Anti-LGBTQI Bill

EU confident Ghana will not sign Anti-LGBTQI Bill

Suspend implementation of Planting for Food and Jobs for 2024 - Stakeholders

Suspend implementation of Planting for Food and Jobs for 2024 - Stakeholders

Tema West Municipal Assembly gets Ghana's First Female Aircraft Marshaller as ne...

Tema West Municipal Assembly gets Ghana's First Female Aircraft Marshaller as ne...

Dumsor is affecting us double, release timetable – Disability Federation to ECG

Dumsor is affecting us double, release timetable – Disability Federation to ECG