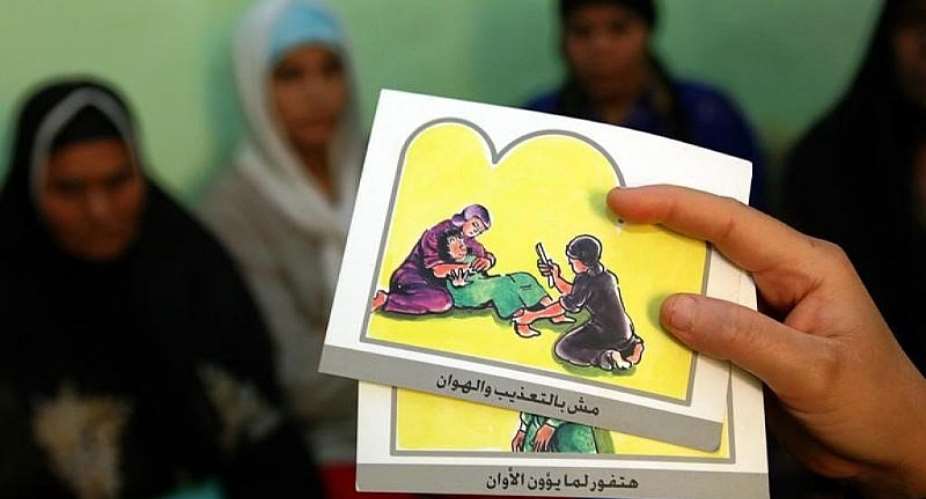

Female Genital Mutilation, or FGM, is torture, according to the United Nations. It is a human rights violation and an extreme form of discrimination against girls and women. Where did the practice originate – and why does it continue? RFI's Anne-Marie Bissada went to Egypt to ask the questions.

Unlike male circumcision, female circumcision can have long-lasting medical and emotional impact. The practice has no proven medical benefit – and it can result in death.

Mona Ali

In a small village outside the Egyptian city of Mansoura, I meet 42-year old Mona Ali.

She warmly welcomes me into her home where I meet two of her three daughters.

She's adamant about stopping FGM after her own personal experience – and especially after what her first daughter went through.

“My eldest daughter was circumcised because at the time my in-laws were alive, so they put a lot of pressure on me. I was not as mature as I am now, so I let it happen,” Ali tells me.

As is usually the case, Ali didn't tell her daughter what was about to happen. “I told her nothing. We don't speak to young girls about this, it's not appropriate.”

Her daughter was taken to a physician and accompanied in the operating room by a neighbour who held her down during the procedure.

She nearly died from a hemorrhage.

From that moment, Ali began to research FGM. She informed herself online and through television and became more aware of the serious risks. She has since refused FGM for her two other daughters.

(This is an edited version of an interview that is part of the Mid-East Junction podcast. Subscribe here)

High rates of FGM

At present FGM is practiced across many countries, mostly concentrated in Africa, says Claudia Cappa, a senior advisor on statistics at UNICEF and author of the comprehensive 2013 report on FGM and on a recent one published this year.

“We know the practice also exist in many countries in the Middle East and in some parts of Asia,” she added.

The latest global figures indicate that some 200 million girls and women have undergone FGM – 50 million of them in the Middle East and North Africa.

Among Middle Eastern countries, Egypt has the highest rate of FGM (it is also ranked fourth in Africa).

Cases in the Middle East are limited to Iraq, Iran, Yemen and Oman, and are less than one percent.

In Egypt, the scales are tipped in entirely the opposite direction: 92 percent of women between the ages of 17 to 42 have undergone FGM, according to Reda Eldanbouki, a human rights lawyer and executive director of the Women's Centre for Guidance and Legal Awareness in Mansoura, Egypt.

Defining FGM and the four types

The World Health Organization defines FGM as: "All procedures that involve partial or total removal of the female external genitalia or other injury to the female genital organs for non-medical reasons."

A paper published in 1985 by Leonard J. Kouba and Judith Muasher outlines these four types.

Most girls in Egypt undergo FGM type 2 or 3 between the ages of 4 and 12.

Assa Hassan

A friend of Mona Ali, Assa Hassan, is a recent convert to ending FGM.

As I am talking to Ali, 49-year-old Hassan joins us wearing a traditional black niqab. She has her own personal experience with the practice.

When she was a young girl, she recounts, there was a man who would make a yearly visit to her village, to cut the girls who were of age.

But, as Ali pointed out, no one told the girls what was happening.

“When he would arrive in the neighbourhood, the girls knew something was happening. They would get very upset and start crying and screaming,” explains Hassan.

After anxiously waiting in line, when it was her turn, the man looked at her and said, "Come back next year, you're too young."

“That meant I was anxious and worried for the whole year until he came back.”

When he did return, she admits she gave in. "I had to. I knew it was going to happen anyway,” she says.

“It was very, very painful. They had to hold me down. For anaesthetic, all they used was a couple sprays of something which really did nothing. I felt all the pain. I hated the experience.”

The experience was also difficult for her parents. "My father left the house because he couldn't stand the screaming. My mother also left and went to the neighbour's.”

The only people left with Hassan were two strangers: "A man holding me and another stranger doing the cutting. It was very, very painful emotionally.”

Deep-rooted

Despite her traumatic experience, when her own daughter came of age, Hassan was undecided – so engrained is the practice in the culture. But her doubts forced her to get a medical opinion.

The doctor examined her daughter and recommended she should undergo the procedure, because her clitoris was enlarged.

Hassan decided to go ahead with the procedure, in a private medical facility instead of with the village cutter. Her decision angered not just her daughter, but her husband too.

Since then, she has learned more about FGM, and her doubts have been confirmed.

She points to the fact that cutting is not a Muslim practice – it's not in the Koran. "We were created like this," she says. "This was God's will – and no one should come and change it.”

Reasons for FGM

Some advocates of FGM invoke medical reasons – for example, hygiene, or an enlarged clitoris that should be cut, as was the case for Hassan's daughter.

Reda Eldanbouki says they are worried about two things: "Firstly, some believe the clitoris causes a bad odour, so it's clean to remove it. Secondly, it can make a woman more sexually aroused which can lead to fornication. They want to 'protect' the woman from these sexual urges."

Put simply, it's about ensuring her virginity is intact.

So how did this brutal procedure ever come about? There are several theories in circulation.

One goes back to the days of rampant slavery, thousands of years ago, well before Judaism, Christianity or Islam.

According to a publication by scholar Gerry Mackie, one way for a slave-trader to get more money was to sew up their young female slaves, according to type 4 FGM practice, in order to fetch a better price.

Another monetary explanation relates to a woman's worth at marriage: if her virginity is intact, she's worth more. Type 4 FGM generally guarantees this. It also protects women from rape.

Origins of FGM

When it comes to the exact origins of the practice, many fingers point to one country or at least one region in particular

In their paper, Kouba and Muasher say circumcised women had been discovered among the mummies of ancient Egyptians. The famous Greek historian, Herodotus, also noted circumcision being practiced on both men and women in Egypt during the 5th century BC.

Mackie notes in his research that reference to FGM go back even further to 2nd century BC among tribes living on the western coast of the Red Sea.

That narrows it down to Egypt, Sudan, Eritrea and Djibouti.

FGM predates both Islam and Christianity in these regions, and therefore remains prevalent in both communities.

Fighting back

Across Egypt and in neighbouring countries, the campaign to end FGM is gathering momentum, and the voices speaking out against it growing louder.

As awareness about grows, more people, like Mona Ali and Assa Hassan are joining the fight to challenge and change the tradition.

This story was produced for the Mid-East Junction podcast.

We’ll no longer tolerate your empty, unwarranted attacks – TUC blasts Prof Adei

We’ll no longer tolerate your empty, unwarranted attacks – TUC blasts Prof Adei

Bawumia donates GHc200,000 to support Madina fire victims

Bawumia donates GHc200,000 to support Madina fire victims

IMF to disburse US$360million third tranche to Ghana without creditors MoU

IMF to disburse US$360million third tranche to Ghana without creditors MoU

Truck owner share insights into train collision incident

Truck owner share insights into train collision incident

Paramount chief of Bassare Traditional Area passes on

Paramount chief of Bassare Traditional Area passes on

Two teachers in court over alleged illegal possession of BECE papers

Two teachers in court over alleged illegal possession of BECE papers

Sunyani: Victim allegedly shot by traditional warriors appeals for justice

Sunyani: Victim allegedly shot by traditional warriors appeals for justice

Mahama vows to scrap teacher licensure exams, review Free SHS policy

Mahama vows to scrap teacher licensure exams, review Free SHS policy

Government will replace burnt Madina shops with a new three-story, 120-store fac...

Government will replace burnt Madina shops with a new three-story, 120-store fac...