‘It is indeed unfortunate that so much Nok material has been looted over time to supply the international art market. Properly excavated, such pieces might have shed valuable light on the Nok culture.’ Ekpo Eyo (1)

When I heard that Nigeria was celebrating the return of her lost treasures and that the Nigerian Commission on Museums and Monuments (NCMM) was organizing an exhibition entitled ‘ The Return of the Lost Treasures: An Exhibition of Repatriated Artefacts ”, I was, to put it mildly, flabbergasted. (2) Had I missed very important messages within the current year regarding the probable return of the famous Nigerian treasures about which the great Ekpo Eyo (3) had written so eloquently and with great erudition in his last work, Masterpieces of Nigerian Art? Had I misread obvious signs that the Americans, British, Dutch, French and Germans had changed fundamentally their persistent and perverse attitude towards the issue of restitution of looted and stolen African artefacts? The last suggestion we heard from Western museums was a ridiculous scheme resulting from the miserable Benin Plan of Action for Restitution, to set up a Western museum in Benin where some of the Benin artefacts, still in Western ownership, would be displayed in Benin City. (4) Had this insulting scheme been suddenly abandoned in favour of doing the right thing, namely, returning the artefacts to the owners?

If Nigerians are celebrating the return of the treasures that had been looted in 1897 in the notorious invasion of Benin by the British or treasures which have otherwise been illegally transferred from the country and are decorating museums and other institutions in the West, then I surely want to be in Nigeria. I want to be there dancing with the masses. But where are my dancing shoes? Do we Africans ever need dancing shoes before we can dance? Surely,this is one of the foolish ideas we have inherited from the colonialists.

With or without dancing shoes, we can express our great joy at seeing those treasures which have been taken away with great violence by those who allegedly were bringing us civilization. But before getting too excited, let me check on what has really been returned, which noble Benin aristocrats are among the returned exiles from the British Museum, the Berlin Ethnology Museum, the World Museum, Vienna and elsewhere.

Readers will recall that we have defined restitution of artefacts to include, inter alia, these points:

a. The object must be with a person, an institution or museum that pretends to have a right to keep it.

b. The object would normally have a name or description known by both sides.

c. The object would in most cases be in a known place in the museum or institution.

d. Attempts would have been made to recover the object.

e. The artefact has been released by the institution holding it. (5)

When I contacted a friend, he wrote back saying:

‘Forget your dancing shoes. Nobody here, in Benin City, Abuja or Lagos is dancing for joy at the return of the artefacts displayed. None of the famous Nigerian artefacts we are passionate about is among the lot displayed in the exhibition,’ The Return of the Lost Treasures: An Exhibition of Repatriated Artefacts’. Queen-Mother Idia, Oba Akenzua I, Oba Ewuakpe and their retinue are still in European detention. You may however, wish to keep your dancing shoes to dance in sorrow for Nigeria. I know your people dance in sorrow as well as in joy.’

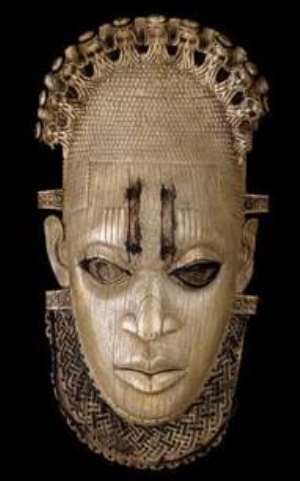

I was sobered to hear that the returned artefacts did not include the famous ivory hip-mask of Queen Mother Idia from the British Museum, or the bust of Queen-Mother Idia from Ethnology Museum, Berlin, or a Commemorative Head from the World Museum Vienna. But are there many Nigerian treasures abroad that are not in the museums or private Western homes or unknown to us and the colleagues concerned with restitution?

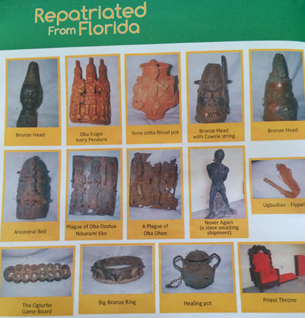

Looking at the images of the returned artefacts, I immediately sensed that this was not the moment we have all being waiting for: the moment that the Western States and their museums would finally agree that it is indefensible to hold on to looted/stolen Nigerian and other African artefacts and have agreed to return them. Could the Ethnology Museum, Berlin, holding 508 Benin artefacts, World Museum, Vienna, holding 167 Benin artefacts, and British Museum, holding 900 Benin artefacts, not afford to release some of these Nigerian objects? Have the Nigerian objects become indispensable for the very survival of these venerable European museums? (6)

Most of the artefacts displayed in the current exhibition appear inferior in quality to the Nigerian artefacts that are at present in Western museums, in Boston, London, Berlin, Paris and elsewhere. One might even wonder if they are not fakes. Have any tests been done in this regard? The assembled objects are mainly artefacts that various customs departments and police have seized in attempts by unscrupulous persons to smuggle them to the United States, France, Switzerland, and other European countries. These objects have been returned as a matter of routine and co-operation between customs of Nigeria and the States concerned. They were not returned because of demand by Nigeria and indeed, in many cases, Nigerian authorities would not even be aware that such objects have been taken out of the country until they are seized. The objects would not even have reached the Western museums and would have no specific name except an identification number used at seizure.

Altar Group with Oba Akenzua I, Benin, Nigeria, now in Ethnological Museum, Berlin, Germany.

How do previously unknown smuggled artefacts of no significant artistic quality become national Nigerian treasures when they are returned to Nigeria? How come that those who have been devoting special attention to looted/stolen Nigeria artefacts are not aware of these Nigerian treasures that do not appear in authoritative works as those by the great Ekpo Eyo and others? Does the very fact of a smuggled artefact being returned from abroad make it a treasure even if it may be a fake? And how do artefacts seized at a Nigerian border, Owode Border, that presumably never left Nigeria qualify as returned lost treasures?

If one is surprised at the quality of the objects displayed in an exhibition with such a grandiose title, one is equally amazed at the statements made in connection with this exhibition. A foreword in the exhibition brochure states, inter alia, as explanation for the difficulty in recovering looted artefacts that:

‘This is because the rich nations of the West holding the cultural patrimony of other countries have been unwilling to see their museums and galleries emptied as a consequence of returning these works of art. Nigeria especially, being so rich in material culture, is among the hardest hit’.

This sentence at the beginning of the foreword, consciously or unconsciously, restates the unfounded and discredited argument of the universal museums which has been rejected several times. This defence is clearly a figment of the disturbed imagination of a director of a universal museum who wakes up in the night, sweating and shaken, worried that he might have lost all the ill-gotten artefacts in his museum. In real life, no such nightmare occurs. Even in the case of the museum with the greatest number of looted/stolen objects, the British Museum, it is not likely that its 9 million artefacts will disappear overnight because of claims for restitution. The so-called floodgates theory that if you return the Benin Bronzes to Nigeria, Greece would follow with request for the Parthenon Marbles, and Ghana, Iraq, Iran, India and a few more States would follow is also unrealistic. As far as we know, hardly anybody wants to empty the universal museums of all their artefacts. It is the dishonest ploy of the universal museums that suggests that if one asks for the return of some important Benin Bronzes that one is asking for all Nigerian artefacts to be returned. It is a refusal to consider a specific request by inflating it to cover hundreds of objects. This mischievous argument has been used by such museum directors as Philipe de Montebello in response to a suggestion by this author that some of the looted Benin Bronzes should be returned to Nigeria. (7)

By highlighting the floodgates argument, used in response to demands for restitution, the brochure for the exhibition, clearly places the displayed objects within the framework of restitution. Yet, as the organisers themselves would be the first to admit, many of the displayed objects do not come from museums and are not the results of restitution demands. They are the results of normal co-operation between police and customs departments of various countries and their counterparts in Nigeria, a collaboration that has yielded welcome results. But must this be confused with the intractable demands and refusals for restitution of Nigeria’s cultural icons in the British Museum, London, Ethnology Museum, Berlin, World Museum Vienna, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Metropolitan Museum of Fine Arts, New York? One cannot avoid the impression that the possibility of confusion between restitution by museums and returns by customs and police departments does not worry the organisers. Throughout the whole exhibition and from the statements relating thereto, this tendency is not discouraged.

Another astonishing statement in the forward is the attempt to create the impression that a policy of collaboration with UNESCO and other international bodies has only recently begun under the present leadership of the National Commission on Museums and Monuments:

‘However, Nigeria through the Management of the National Commission for Museums and Monuments realizing the futility of confrontation in bringing back its cultural relics carted away largely during colonial period decided to adopt a new approach in tackling the problem.

‘A new culture of collaboration’ was adopted. This essentially has to do with opening communication channels with countries/institutions holding its objects within the context of UNESCO, ICOM and other bilateral and multilateral frameworks. Dialogue, Collaboration and Cooperation are the main ingredients of this approach’.

For those familiar with Nigeria’s efforts in the past to recover its looted/stolen artefacts, such statements are surprising. The insinuation that previous managers of the NCMM had been using ‘confrontation’ rather than ‘cooperation’ must come as a shock. Was the great Ekpo Eyo, the first Director-General of the Commission on Museums and Monuments also using ‘confrontation’ (whatever that may mean in this context) rather that co-operation and collaboration? The very first publication of Eyo that I read in this regard contains a report on efforts made through ICOM to obtain Benin Bronzes for the opening of the National Museum in Benin City in 1968: ‘We tabled a draft resolution at the General Assembly of the International Council of Museums (ICOM) which met in France in 1968, appealing for donations of one or two pieces from those museums which have large stocks of Benin works. The resolution was modified to make it read like a general appeal for restitution or return and then adopted.

When we returned to Nigeria, we circulated the adopted resolution to the embassies and high commissions of countries we know to have large Benin holdings but up till now we have received no reaction from any quarters and the Benin Museum stays “empty”. (8) Eyo sounds to me as being very keen on collaboration and co-operation with holders of the Benin Bronzes as well as with ICOM. We do not know of any Director-General of the NCMM who was not keen to cooperate with holders of Benin Bronzes or with ICOM and UNESCO. Indeed, one can say that this will to co-operate with these bodies and holders of looted Nigerian artefacts has been the outstanding characteristic of all Nigerian authorities. Folarin Shyllon has for years advised in this direction and urged the ratification of the UNESCO Convention of 1970 and other international instruments, pointing out the availability of advice and other assistance from the Secretariat.

Bust of Queen-Mother Idia, Benin, Nigeria, now in Ethnologisches Museum, Berlin, projected for transfer to Humboldt Forum, Berlin, Germany.

Where then does this idea of a new approach come from when there has in fact been a continuity of approach? Some evidence would have to be provided that the present administration or management of NCMM is following an approach that differs substantially from that of its predecessors who laid the foundations for the Commission. The foreword tends to amalgamate different events and issues to produce a story that enhances the image of the present leadership of the Commission. With all due respect, collaboration and co-operation with Western museums, UNESCO and ICOM did not start with the present management of the MCNN. Incidentally, when some countries are praised for returning artefacts to Nigeria, one should also add that most of these countries are keeping a large number of superior Nigerian artefacts which they are not in a hurry to return. They even refuse to discuss those objects. Britain that may be said to have begun all this looting of Nigerian artefacts, especially in the 1897 invasion, has kept out of any discussions and did not attend the meeting that adopted the so-called Benin Plan of Action for Restitution .

What is meant by ‘confrontation’ in the context of restitution? When holders of looted Nigerian artefacts proclaim loudly they would not return any of the looted precious artefacts, many remain silent and state they are pursuing quiet diplomacy. But when Nigerians and their supporters suggest that Nigeria should also proclaim loudly and fearlessly its demand for the return of the looted artefacts, some suggest they are seeking confrontation. What is this mentality that proposes that Nigerians act silently and quietly in their demand for the return of looted objects whereas those holding the looted objects loudly and boldly state their refusal to return? There is something fundamentally wrong in a situation where victims of violent military armed robbery are advised to tread carefully in a subservient manner where successors of armed robbers act without inhibition. Who is to be ashamed of his acts? Is this the colonial mentality rearing its head again?

Head of an Oba, Benin, Nigeria, now in Bristol Museum, Bristol, United Kingdom of Great Britain.

One thing that this current exhibition confirms abundantly is that the policy of quiet diplomacy that has been pursued by Nigerian authorities since Independence in 1960 has completely failed. Not even one of the famous iconic artefacts of Nigerian culture which most Nigerians and other Africans know, such as the ivory hip-mask of Queen-Mother Idia, has been returned or is anywhere near the point of return. It is good to have returned artefacts seized by customs and police but this is not what Nigerian governments and peoples have been asking for in all these years: the cries for return are for the iconic national treasures that are in Western museums and institutions. Objects, probably fakes for the illegal Western market, and seized by customs do not per se become national treasures. Or do some people consider that anything that comes from the Western world, even if originally from Nigeria, and even if a fake, becomes a national treasure?

An aspect of the exhibition that must be considered carefully is its possible effects on impressionable persons coming to these matters for the first time. They are told that these are Nigerian treasures and have no reason to doubt the experts but are they really? By which criteria have these objects that until the present exhibition were not known even to the experts become Nigerian treasures? If we compare their quality with those of undoubted treasures of Nigerian art, such as the ivory hip-mask of Idia in British Museum, we see and feel immediately the difference. Is there not a danger of lowering standards for future generations of Nigerians and Africans?

We will not comment on many of the statements made in connection with this exhibition. Statements such as ‘culture is more important than petroleum’ surprised me. Is there any contest between culture and petroleum and what is the significance of this comparison in the context of restitution? Clearly there remains much more to do if Nigeria is to recover any of its iconic artefacts from Western institutions. To continue to pursue a policy which in some 57 years has brought no tangible results except insults and aspersions on the ability of Nigeria and Nigerians to protect their artefacts, cannot be advisable. The NCMM seems to recognize this failure when it writes in the brochure to the exhibition:

‘However, the pressure for the return of these objects must be intensified as repatriated collection presently in the collection of the Commission is like a drop of water in the ocean compared to the huge number of antiquities outside the country’.

This admission comes after several attempts, including this exhibition itself, to present Nigeria’s policy in the matter of restitution as a success story even though all observers recognize that none of the real treasures of Nigeria has been returned through the efforts of the Commission. There was the voluntary return of Benin artefacts by a British citizen, Dr. Adrian Mark Walker and the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston USA, voluntarily returned some artefacts. France, Canada, USA, and Switzerland also returned objects seized by their Customs Departments in the normal execution of their duties. Hardly any pressure has been exercised by the Nigerian authorities on the holders of Nigeria’s treasures. There is a great reluctance even to publish a list, however partial, of Nigerian artefacts abroad that one seeks repatriated. We have not seen any appeal or request by the Nigerian authorities to the holders of Nigerian artefacts in the Western world even though it is obvious that a request, even to individuals, might result in some individual returns. Most people in the Western world are not even aware that Nigeria is seeking its artefacts returned. How should they know when no attempts are made to reach them? Even some Western museums continue saying Nigeria has not made any requests for return of artefacts. What prevents the Commission from sending such requests to the main museums? There is hardly any information to the Nigerian and international public about such efforts, presumably they are incompatible with quiet diplomacy.

As we have seen above, the Director-General of the NCMM has declared that ‘the pressure for the return of these objects must be intensified’. Is this ‘confrontation’ or ‘quiet diplomacy’? We would like to assist in this effort by making the following suggestions that are perhaps ‘confrontational’:

1. The Nigerian Government should write to all known or major museums in the Western world requesting the return of Nigerian artefacts that may have been stolen, looted, or acquired under dubious circumstances, including especially the Benin artefacts that were looted in the British invasion of 1897. Copies of such a request should be widely circulated and posted on the internet. Thenceforth no reputable museum could pretend it had never heard of such a request as the Ethnology Museum Berlin, Germany, continues to assert and has been so quoted in the German Parliament and by the German Federal Ministry of Foreign Affairs. That statement has so far not been challenged by any Nigerian official.

2. Nigerian Government officials and specialists should be sent to major Western museums to establish a list of Nigerian artefacts held abroad, specifying e.g. the number of Benin artefacts held by each museum. The day and time of such visits should be publicly announced. So far most Western museums have not been willing to release such figures.

3. Nigerian Embassies and Missions abroad should be required to pay attention to events and activities where Nigerian cultural artefacts may be involved and to report accordingly to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Ministry for Culture. They should also inform about all relevant matters and send corresponding documentation.

4. The Nigerian Diaspora which consists of thousands of persons with varied qualifications and experiences, including artists and cultural activists should also be involved in the efforts to secure the return of Nigerian treasures from abroad. One Diaspora group was effective in obliging Cambridge University to consider the possible return of the Okukor ,the Cambridge Cockerel, whilst another Diaspora group effectively prevented the sale of a Queen-Mother Idia sculpture. Efforts should also be made to avoid museums and other foreign institutions using the presence of the Diaspora as raison d’être of looted/stolen Nigerian artefacts in their area.

5. The policies and activities of the Nigerian Government in the recovery of Nigerian artefacts abroad should be brought to the attention of the public in Nigeria and in Western countries; to this end, all means of modern communication and mass media should be explored.

6. The efforts of the Nigerian Government in the recovery of artefacts abroad should always be brought to the attention of international organizations, including the United Nations, UNESCO and ICOM as appropriate, using their assistance wherever relevant.

7. No government official or any person in the employment of the Government shall assist officially and knowingly in events, exhibitions and other activities involving the display or use of looted/stolen Nigerian artefacts. Similarly, no foreword, introduction, essay, or note shall be prepared by a Nigerian official for publication in a catalogue or book that is mainly intended to promote the sale of looted/stolen Nigerian artefacts. There has been a case where a Nigerian Permanent Secretary has written a foreword to a book dealing mainly with looted Nok sculptures. When in doubt, the official concerned shall consult the Ministry for Culture.

8. A new and comprehensive legislation should be enacted covering antiquities, taking into account the various proposals that have been made by Nigerian experts

9. A website shall be set up by the Ministry for Culture for information and discussion of all the above-mentioned matters by officials and non-officials.

10. The Nigerian Government and other Nigerian institutions shall make it abundantly clear that there is no intention of allowing foreign museums and institutions to arrogate to themselves the duty of transmission of Nigerian culture to the Nigerian Diaspora. Relations between the Nigerian Government and the Nigerian Diaspora shall be direct. The Nigerian Diaspora shall be entitled to seek from Nigerian authorities and institutions any help and information it desires as regards Nigerian culture.

11. Every attempt should be made to encourage Nigerian and Diaspora artists, singers, and writers to explore the above themes in their works. The Government shall inform the artists of what assistance the Government can provide.

12. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Ministry for Culture shall establish co-operation between Nigeria and States such as China, Egypt, Greece, Italy, Turkey, and others to revive and pursue the objectives set by the 2010International Conference on Restitution that was held in Cairo, Egypt.

13. The Government should bring to the attention of the United Nations, UNESCO and ICOM and other organizations that have passed uncountable resolutions on return of cultural property , the inability/ unwillingness of certain Member States to fulfil their obligations. Nigerian Missions should bring to the attention of all concerned the position of the Government and report accordingly.

14. An annual report shall be prepared by the Ministry for Culture, assisted by the National Commission on Museums and Monuments, on the above matters entitled ‘Recovery of Lost/looted/stolen Nigerian Artefacts’. The report shall be made available to the Nigerian public and copies sent to leading museums.

Pair of leopard figures, now in the Royal Collection Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II, London, UK. The commanders of the British Punitive Expedition force to Benin in 1897 sent a pair of leopards to the British Queen soon after the looting and burning of Benin City.

If Nigeria, with all its resources, material and human, cannot after 57 years of Independence persuade the former colonial power and its allies to return some of the undoubtedly looted Nigerian cultural artefacts, then one must reconsider the often stated ‘manifest destiny’ of that great country on our Continent. The African Continent has more intractable problems that require serious and resolute leadership.

Fear of confrontation (whatever that means) and a subservient attitude in reclaiming what obviously belongs to Nigeria, are not recommendations for the determined and decisive leadership that the African Continent sorely needs.

Kwame Opoku, 17 July 2017

NOTES

1. Ekpo Eyo, From Shrines to Highlights: Masterpieces of Nigerian Art, Federal Ministry of Information and Communication, Abuja, 2010, p.23.

2. Culture more important to Nigeria than petroleum - Lai Mohammed ...

www.vanguardngr.com › News

NCMM Celebrates Return Of Lost Treasures In An Exhibition Of ...

www.nico.gov.ng/.../1925-ncmm-celebrates-return-of-lost-treasures-in-an-exhibition-

In Lagos, lost treasures brings hope in artefacts repatriation — Arts ...

https://guardian.ng/art/in-lagos-lost-treasures-brings-hope-in-artefacts-repatriation

In Lagos, lost treasures brings hope in artefacts repatriation | 2effizy.com

www.2effizy.com/2017/.../in-lagos-lost-treasures-brings-hope-in-artefacts-repatriation.

3. Ekpo Eyo, op.cit.

4. K. Opoku, European museums to 'loan' looted Benin bronzes to Nigeria ... https://www.pambazuka.org/.../european-museums-‘loan’-looted-benin-bronzes-niger..

European museums to 'loan' looted Benin bronzes to Nigeria? - Scoop.it

www.scoop.it/t/.../p/.../european-museums-to-loan-looted-benin-bronzes-to-nigeria

5. K. Opoku, ’What we understand by restitution,’’ https://www.modernghana.com

6. See annex below.

See also Kwame Opoku: Blood Antiquities In Respectable Havens: Looted ...

www.africavenir.org/fr/.../kwame-opoku...in...benin-artefacts.../print.html?.

7. Kwame Opoku´s response to Philippe de Montebello - AFRIKANET.info

www.afrikanet.info/archiv1/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id..

8. Museum, Vol. XXL, no 1, 1979,’ Return and Restitution of cultural property’, pp.18-21, at p.21, Nigeria.

Commemorative Head, Benin, Nigeria now in Weltmuseum, Vienna, Austria.

Commemorative Head, Benin, Nigeria now in Weltmuseum, Vienna, Austria.

ANNEXLIST OF HOLDERS OF BENIN BRONZES

Almost every Western museum has some Benin objects. Here is a short list of some of the places where the Benin Bronzes are to be found and their numbers. Various catalogues of exhibitions on Benin art or African art also list the private collections of the Benin Bronzes. Many museums refuse to inform the public about the number of Benin artefacts they have and do not display permanently the artefacts in their possession since they do not have enough space. A museum such as Völkerkundemuseum, Vienna, now Weltmuseum, has closed since 17 years (2000-2017) the African section where the Benin artefacts are, apparently due to repair works which are not likely to be finished before 2017.

Berlin – Ethnologisches Museum 580.

Boston, - Museum of Fine Arts 28.

Chicago – Art Institute of Chicago 20, Field Museum 400

Cologne – Rautenstrauch-Joest-Museum 73.

Glasgow _ Kelvingrove and St, Mungo's Museum of Religious Life 22

Hamburg – Museum für Völkerkunde,

- Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe 196.

Dresden – Staatliches Museum für Völkerkunde 182.

Leipzig – Museum für Völkerkunde 87.

Leiden – Rijksmuseum voor Volkenkunde 98.

London – British Museum 900.

New York – Metropolitan Museum of Fine Art 163.

Oxford – Pitt-Rivers Museum/ Pitt-Rivers country residence, Rushmore in Farnham/Dorset 327.

Stuttgart – Linden Museum-Staatliches Museum für Völkerkunde 80.

Vienna – Museum für Völkerkunde now World Museum 167.

Ekpo Eyo’s, Masterpieces of Nigerian Art

Most of the Nigerian artefacts shown in Eyo’s, Masterpieces of Nigerian Art, (2010) are in Western institutions. See K. Opoku, Excellence and Erudition: Ekpo Eyo’s Materpieces of Nigerian Art. ... https://www.modernghana.com/.../excellence-and-erudition-ekpo .

We noted the following locations of Nigerian masterpieces:

Musée du quai Branly, Paris, France.

Musée Barbier-Mueller, Geneva, Switzerland.

Dept. of Art History and Archaeology, University of Maryland, USA,

British Museum, London, United Kingdom.

Detroit Institute of Art, Detroit, USA.

National Museum of African Art, Smithsonian Institutions, Washington, USA.

Toledo Museum of Art, Toledo, USA

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, USA.

Museum Rietberg, Zürich, Switzerland.

Ethnologisches Museum, Berlin, Germany.

Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco, USA.

Völkerkunde Museum (now Weltmuseum), Vienna, Austria.

Royal Collection, Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II, London, United Kingdom.

New Orleans Museum of Arts, New Orleans, Louisiana, USA.

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, USA.

Yale University Art Gallery, Connecticut, New Haven, USA.

Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond, Virginia, USA.

Indiana University Art Museum, Bloomington, Indiana, USA.

Tuesday’s downpour destroys ceiling of Circuit Court '8' in Accra

Tuesday’s downpour destroys ceiling of Circuit Court '8' in Accra

SOEs shouldn't compromise on ethical standards, accountability – Akufo-Addo

SOEs shouldn't compromise on ethical standards, accountability – Akufo-Addo

Father of 2-year-old boy attacked by dog appeals for financial support

Father of 2-year-old boy attacked by dog appeals for financial support

Jubilee House National Security Operative allegedly swindles businessman over sa...

Jubilee House National Security Operative allegedly swindles businessman over sa...

Nobody can order dumsor timetable except Energy Minister – Osafo-Maafo

Nobody can order dumsor timetable except Energy Minister – Osafo-Maafo

Mahama wishes National Chief Imam as he clock 105 years today

Mahama wishes National Chief Imam as he clock 105 years today

J.B.Danquah Adu’s murder trial: Case adjourned to April 29

J.B.Danquah Adu’s murder trial: Case adjourned to April 29

High Court issues arrest warrant for former MASLOC Boss

High Court issues arrest warrant for former MASLOC Boss

Align academic curriculum with industry needs — Stanbic Bank Ghana CEO advocates

Align academic curriculum with industry needs — Stanbic Bank Ghana CEO advocates

Election 2024: We'll declare the results and let Ghanaians know we've won - Manh...

Election 2024: We'll declare the results and let Ghanaians know we've won - Manh...