Ghana has abundant salt deposits but is unable to satisfy West African demand let alone successfully compete with global producers. Known as 'white gold', salt is one of the most common minerals on the planet and throughout history has served as an important foundation of civilisation. Its importance cannot be over stated as there are about 14,000 documented benefits of salt, both medicinal and industrial. Salt deposits are inexhaustible but the demand is enormous and currently outstrips supply.

About 100 countries in the world produce and refine salt. From Alaska to Tierra del Fuego, the Americas produce almost as much salt as the rest of the world combined. The US is the leading global producer thanks to the Great Salt Lakes. It is responsible for 22 per cent of the total world production capacity.

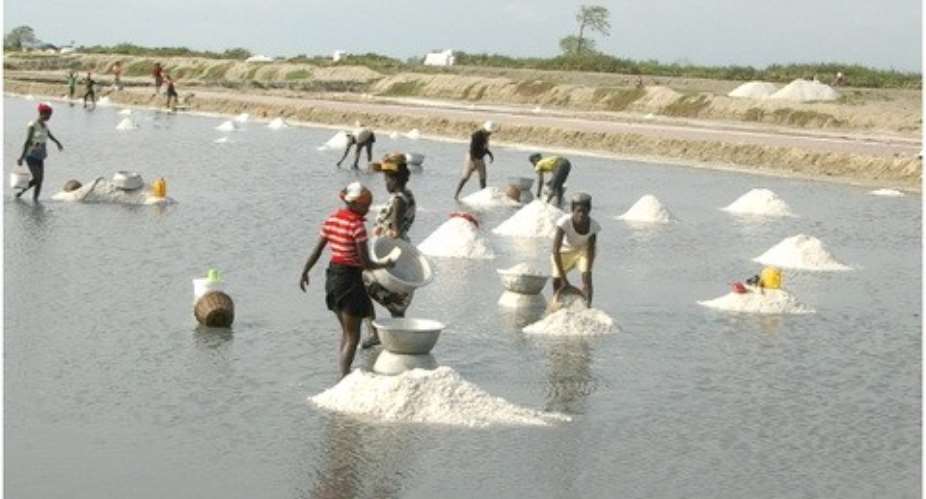

Salt production in Ghana started in the 19th century and, aside from fishing, it is the major economic activity of people along its 500km coastline. The salt producing areas in Ghana include the Keta lagoon, the Songhor lagoon, the Densu Delta area, Nyanya lagoon, Oyibi lagoon, Amisa lagoon, Benyah lagoon.

Salt as a renewable natural resource contributes billions of Ghana cedis annually to the economy and employs more than 1,500 people. In the ECOWAS sub-region, the demand for industrial salt is estimated at over 3 million tonnes. Ghana and Senegal, the biggest regional players, possess all the right conditions for commercial salt production and together produce 350,000 tonnes per year. But this is not enough to satisfy demand and imports from Brazil, Australia and Europe make up the shortfall.

Research indicates that Ghana has a potential production capacity of more than two million tonnes, but can only manage a maximum of 250,000 tonnes, which represents just 10 per cent of what nature offers on the coast.

For example, although the Songhor Salt Project in the Greater Accra Region has the potential of producing over 150,000 tonnes of the mineral annually, its current output hovers at around 60,000 tonnes, a slight increase on last year's 46,000 tonnes. Togo, Benin, Burkina Faso, Cote d'Ivoire and Niger are among the countries Ghana exports to. Nigeria represents the biggest regional market, but imports high quality salt from Brazil.

At the present rate of production Ghana would be unable to meet the demands of its embryonic petrochemical industry, which requires substantial quantities of salt, and it is likely that Brazil, China, Australia or India would fill the gap. The main challenge facing the industry is lack of start-up capital as well as capital for expansion.

“Salt production is a capital intensive business,” explained Ernest Osei, CEO of Tradevco Salt Production and Trading Company Ltd told the media last year.

“You cannot easily access funding from banks and the cost of borrowing is very expensive in this country. When you go for a loan, it starts attracting interest, even when operations of the company have not started, so you end up paying for something you haven't yet produced.”

As it stands, many salt producing companies that obtained concessionary loans from the commercial banks have run into huge debts. Others have been unable to secure loans, due to unwillingness of some Designated Financial Institutions (DFIs) to market and disburse the funds. Some companies have folded as a result, while others struggle to break even.

Another block to the industry's expansion is the difficulty of acquiring coastal land because of legal technicalities or communal tussles over ownership. One such area is Ada, which has been at the centre of stand-offs between local authorities and salt investors. Apart from questions of land ownership, salt is a traditionally venerated mineral and many communities resist what they consider industrial interference. Compared with many of its competitors, Ghana's salt production technologies are obsolete.

The US and India employ state-of-the art-salt harvesters that are able to collect large quantities of salt within a short time. Ghana's reliance on more artisanal forms of production comes down to lack of capital. Currently, the industry relies on solar salt mining as the main production method due to the geographic location of the reserves as well as the favourable weather.

There is a clamour for a complete overhaul of the industry in order to make it more competitive, drawing in all the stakeholders – the government through the Ministry of Lands and Natural Resources and the Minerals Commission, the National Salt Producers Association of Ghana, coastal land authorities and the investors.

It is believed a salt policy separate from the Minerals and Mining Law would lay to rest or at least alleviate the perennial land acquisition problems. Such a policy would spell out how land containing salt deposits should be acquired, taking into consideration the needs of the state, the host community, the investor and the people of Ghana.

Time is not on Ghana's side given the escalating demand for salt domestically and in the sub-region. Measures must be put in place as soon as possible to help the nation reap the full potential of what nature has freely offered it.

Tuesday’s downpour destroys ceiling of Circuit Court '8' in Accra

Tuesday’s downpour destroys ceiling of Circuit Court '8' in Accra

SOEs shouldn't compromise on ethical standards, accountability – Akufo-Addo

SOEs shouldn't compromise on ethical standards, accountability – Akufo-Addo

Father of 2-year-old boy attacked by dog appeals for financial support

Father of 2-year-old boy attacked by dog appeals for financial support

Jubilee House National Security Operative allegedly swindles businessman over sa...

Jubilee House National Security Operative allegedly swindles businessman over sa...

Nobody can order dumsor timetable except Energy Minister – Osafo-Maafo

Nobody can order dumsor timetable except Energy Minister – Osafo-Maafo

Mahama wishes National Chief Imam as he clock 105 years today

Mahama wishes National Chief Imam as he clock 105 years today

J.B.Danquah Adu’s murder trial: Case adjourned to April 29

J.B.Danquah Adu’s murder trial: Case adjourned to April 29

High Court issues arrest warrant for former MASLOC Boss

High Court issues arrest warrant for former MASLOC Boss

Align academic curriculum with industry needs — Stanbic Bank Ghana CEO advocates

Align academic curriculum with industry needs — Stanbic Bank Ghana CEO advocates

Election 2024: We'll declare the results and let Ghanaians know we've won - Manh...

Election 2024: We'll declare the results and let Ghanaians know we've won - Manh...