One and half years ago, when Ethiopia's Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed decided to punish the Tigrayan People's Liberation Front (TPLF) for their alleged role in attacking a federal military base, it was expected to be a swift operation. Indeed, the Ethiopian government forces, helped by neighbouring Eritrean troops, captured the whole Tigray region, including the rebel capital Mekelle within a month. However, it was just the beginning of a long metastasising war as Ethiopia continues to be at war with itself, and the situation is deteriorating every passing day.

As the battle between the two sides continued, as per different UN reports, the war has left more than 400,000 people in the Tigray region starving, and many children have died of malnutrition. Government forces have also been accused of blocking aid to reach the Tigray region. To make the matter worse, there have been reports circulating of ethnic cleansing against the TPLF supporters in the Western Tigray region. According to Amnesty International, hundreds of unarmed Tigrayan civilians of Axum town in northern Ethiopia were murdered by Eritrean troops.

In the ongoing civil war in Ethiopia, the Government forces face the strong and well-armed TPLF and its allies, including the Oromo Liberation Army (OLA). Those in favour of Abiy argue that Abiy's policies are pan-Ethiopian, and working towards attaining a more unitarian state. On the other hand, rebels' supporters argue that the centralisation of power will curtail the autonomy of ethnic-nationalist forces and, therefore, they are fighting for a federal order.

This ethnicisation of politics is nothing new in Ethiopia, as the country has been suffering from it for decades. When Abiy Ahmed took over as PM in 2018, his coalition dharma raised hopes of gradually overcoming the ethnic animosities between the different tribes. Yet, under his leadership, till November 2020, Ethiopia has witnessed 114 ethnic and religious conflicts. Questions are being raised about whether all these conflicts are manufactured or instigated by external forces with the ulterior motive of leading the country towards Balkanisation and, thus, forcing a regime change.

This suspicion stems from the conflict related to the use of Nile River resources and the construction of a giant dam over it. As per the current agreement based on the 1959 settlement, Egypt receives 55.5 billion cubic meters of Nile water annually, whereas Sudan can draw 18.5 billion cubic meters. Ethiopia receives no water from the Nile. In November 2010, Ethiopia decided to alter the arrangement by announcing its plan to construct a giant dam, the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD). When completed, the GERD will become the largest hydropower facility in Africa, generating a massive 5150 MW and will be able to maintain water storage of about 74 billion cubic meters.

In 2011, when Egypt was on the verge of the Arab Spring protests, the construction work for the dam started. Politically speaking, Egypt's January 25 revolution and the subsequent volatile domestic politics provided Ethiopia with a critical window of opportunity. In 2012, the then–Egyptian President Mohamed Morsi tried to revive the negotiations and visited Ethiopia. However, with Morsi's political demise, the negotiation process stopped. Negotiations resumed in Khartoum in November 2013, followed by another round in January 2014. In 2015, Ethiopia, Egypt and Sudan signed a cooperation settlement with a seven-year timeline for filling the dam. Most recently, in February 2022, Ethiopia started producing electricity using one of the 13 turbines. This has caused near panic among the Egyptians as 97% of its water comes from the Nile.

Egypt has a history of utilising all the approaches, including economic, technological, legal and political, to achieve a consolidated control over Nile water. Since the 1950s, Egypt has impeded Ethiopian dam-building with threats of naval intervention. Throughout history, Egypt has mobilised its resources to prevent the upstream riparian states from mobilising water resources and keep using the water for its benefit, and if the Ethiopian Government is to be believed, Egypt is likely trying to stall the progress of this dam by intensifying its covert and overt activities to destabilise Ethiopia . The blocking of funds from donors could also be one of the tactics used by Egypt.

Lately, Egypt has been accused of assisting the Gumuz militia and soliciting the Government of South Sudan to provide a military base for the militia group. Egypt is also charged with pitting Sudan against Ethiopia by rekindling their conflict over the 260-square-kilometer al-Fashaqa region. Finally, Egypt has been continuously seeking a rapprochement with Somalia. In 2020, Egypt in vain solicited the support of the Federal Government of Somalia by promising military aid. Later it also turned to Somaliland to establish a military base.

In May 2021, Egypt held joint military drills with Sudan and dubbed the exercises in most unsubtle terms as "Guardians of the Nile". Egypt is also playing its soft diplomacy card in the East African region. In November 2021, Egypt hosted the Tanzanian President Samia Suluhu Hassan and discussion over the future of GERD was on the top of the agenda. Egypt is also trying to befriend Kenya as an upper riparian country. Kenya is also a non-permanent member of the UN Security Council, currently representing Africa.

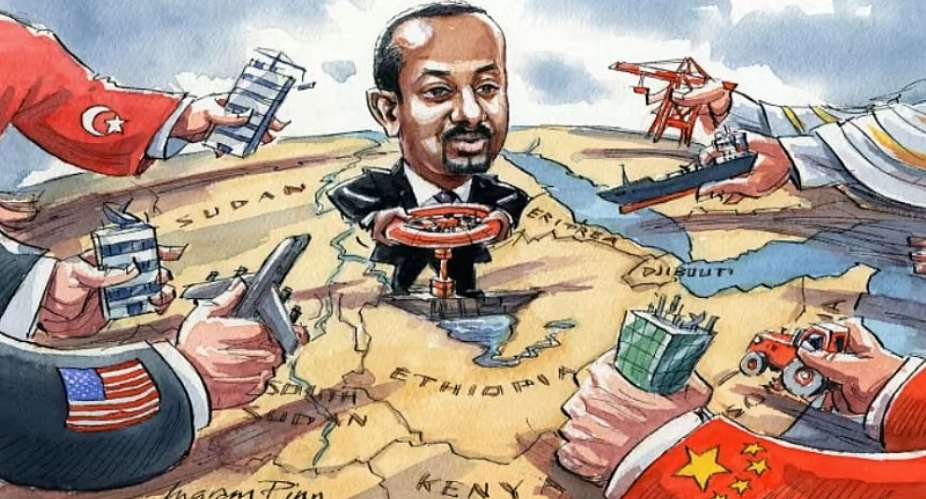

The geopolitics over Ethiopia is not restricted to Egypt only. In addition to Egypt and other co-riparian states along the Nile, 11 in total and many other international players are also seeking different ways to control Ethiopia. While some countries are competing to finance development projects, there are others that want to influence government policies for various reasons. For example, it is highly likely that Egypt has the tacit support of the USA. On the other hand, the African Union (AU) is suspected to be taking the Ethiopian side.

Meanwhile, Ethiopia has improved its ties with Turkey. Their recent rapprochement includes the purchase of drones from Ankara. The UAE has close relations with Sudan, Ethiopia, Egypt, and Eritrea. Meanwhile, the Biden administration wants to ensure that Russia doesn't exploit the situation. Manifestly, the vested interests of each stakeholder --resulting in conflicting policies -- are pushing the volatile Horn of Africa to become a region of endless wars and destructions.

Way Forward

Ethiopia holds the key to the fight against terrorism in the region as well as at the continental level. This was exemplified in 2006 when Ethiopia sent its troops to neighbouring Somalia to fight the Islamist militants. Ethiopia is also a strong supporter of the Intergovernmental Authority of Development (IGAD), an inter-country body to fight against terrorism at the continental level. Ethiopia also contributes the maximum number of troops to UN peacekeeping forces. Barring the present feud, Ethiopia has always been on good terms with the USA. Ethiopia also shares a very close relationship with Russia and China.

Dogged persistent diplomacy by the African Union and other foreign parties resulted in Abiy Ahmed announcing a "humanitarian truce" on March 24. However, this is too little considering the need. The consequences of the unfolding disaster should worry the world. With the fate of 115 million Ethiopians hanging in a precarious balance, concerted efforts from the world leaders will be required to prevent this imminent massacre. The price of inaction would be high.

By Samir Bhattacharya

The author is Research Associate with the Vivekananda International Foundation. The views expressed are personal.

This IMANI job no dey pap; the people you are fighting for are always fighting y...

This IMANI job no dey pap; the people you are fighting for are always fighting y...

Prof. Naana Opoku-Agyemang has changed; you can see a certain sense of urgency –...

Prof. Naana Opoku-Agyemang has changed; you can see a certain sense of urgency –...

MFWA Executive Director slams Akoma FM for engaging in ‘irresponsible’ media pra...

MFWA Executive Director slams Akoma FM for engaging in ‘irresponsible’ media pra...

‘Women must become millionaires too’ — Prof Jane Naana on establishment of Women...

‘Women must become millionaires too’ — Prof Jane Naana on establishment of Women...

Some believe only in Ghanaian votes, not Ghana — Kofi Asare jabs politicians

Some believe only in Ghanaian votes, not Ghana — Kofi Asare jabs politicians

Plan to make BEST sole aggregator of Sentuo Oil Refinery will create market chal...

Plan to make BEST sole aggregator of Sentuo Oil Refinery will create market chal...

2024 elections: I can't have the man I removed from office as my successor — Aku...

2024 elections: I can't have the man I removed from office as my successor — Aku...

2024 Elections: Immediate-past NPP Germany Branch Chairman garners massive votes...

2024 Elections: Immediate-past NPP Germany Branch Chairman garners massive votes...

Gov’t focused on making Ghana energy self-sufficient, eco-friendly – Akufo-Addo

Gov’t focused on making Ghana energy self-sufficient, eco-friendly – Akufo-Addo

April 25: Cedi sells at GHS13.74 to $1, GHS13.14 on BoG interbank

April 25: Cedi sells at GHS13.74 to $1, GHS13.14 on BoG interbank