“The time has come for Africa to stand up and fight with one voice the attempts by the metropolitan powers to dictate who is a legitimate leader in Africa and who is not. The history of such dictation shows the pursuit of Western self-interest at the cost of African nationalist interests…To Britain and America, and all their satellites, 'democracy' and 'legitimacy' is when their interests prevail over those of the African people (See Dr. Motsoko Pheko's “New African” “Democracy and Legitimacy in Africa,” Sept. 18, 2013).”

Undoubtedly, Dr. Motsoko Pheko's powerful statement stands in for a capsule of animadversion, a kamikaze rhetorical blow of sorts, surgically leveled against Western incontinent meddling in African affairs under a sanctimonious cassock of cultural constructs skewed toward its strategic interests, of the temperament of economic, political, and cultural hegemony. Nevertheless, the comparative weakness of post-Nkrumah African leadership, characterized by frigid self-interest, avarice, lack of Afrocentric consciousness and of political centering, self-hatred, and intellectual soupiness has meant that African leadership has had to barter the goodwill of the people for a transient material gain. Through this arrangement of unequal dichotomy the West's long-term material gain is collaterally guaranteed via African leadership's unthinking socialization with the outside world. This is a major drawback to Africa's economic and political equalization with the outside world. It also means that political meritocracy loses the shine of moral palatability in the public eye.

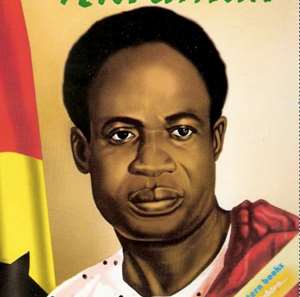

Unfortunately, democracy has become an easy, cheap means to wealth acquisition, socioeconomic control of the powerless, and political aggrandizement in today's world. Therefore, taking inventory of leadership, its credits and debits, via a process of critical assessment, in a neutral manner, of course, may offer practical opportunities for society to acquaint itself with its social ledger of moral strengths and weaknesses. Arguably, leadership emanates from the masses and hence reflects the moral texture of the masses and, therefore, to gauge the moral maturity, or otherwise, of leadership entails another evaluative enterprise, that of establishing a possible behavioral concordance between leaders and the larger societies from which they emanate. Remarkably, this view finds philosophical solace in the crisp contrast between the acquired, forced elitism of Ghana's infamous ethnocratic “village champions” JB Danquah and KA Busia, on the one hand, and the humble backgrounds of Kwame Nkrumah and Steve Biko, on the other hand. Yet Biko's and Nkrumah's relative impact on the world eclipses Busia's and Danquah's.

On the contrary, Mandela's royal background shot him to international approbation on the basis of his humility, his commonsense, and his self-identification with the people! What does this say about the qualitative contrast between humility and bloated hollowness? Essentially, this does not, however, say anything about Biko's and Nkrumah's steadfastness, native intelligence, principled politics, spiritual fortitude, intellectual bravery, honesty, historical consciousness, critical thinking, piercing foresight, fairness, and love of humanity. Good, intelligent, and visionary leaders possess these basic qualities by nature in addition to others. Even so, the social lahar of negative influences, emotional sponginess, and psychological imbalance may usurp these noble qualities. The fact of the matter is that collaborative socialization between the intelligence agencies of the West, primarily of the British (M16), French (ADECE), and American (CIA), and the political intrigues of KA Busia, JB Danquah, and the coup plotters constitute an indelible smirch on their already-checkered legacies. Further, regardless of the miasma of historical revisionism, this factual extract of historical information is already an entrenched clot in the occipital artery of public psychology.

In point of fact, a high-flown revisionist claim advanced by the morganatic scions of the famous terrorists, KA Busia, his National Liberation Movement (NLM), Obetsebi Lamptey, etc., that Nkrumah arrogated full executive powers to himself in the political incarnation of life presidency does not sufficiently affirm another lousy claim, which is that it constitutes a legitimate motivation for or moral causation of the putschism which toppled his progressive government. However, before delving into alternative theories of rationalization it is only appropriate to recapture the caliginous political histrionics of Busia in the aftermath of Nkrumah's political dispensation. The Sallah v. Attorney General (1970) case is one. The Aliens Compliance Order (1969) and the Certificate of Emergency (1971) are another. These three examples should suffice. Regrettably, the intellectual vista of the Oxford-educated sociologist could not anticipate a belated riposte from Nigeria, appearing in the form of a politico-legal avatar of Nigeria's 1983 Expulsion Order, in which many Ghanaians lost their lives, their families, and their properties, while bringing the good name of Ghana into disrepute. Busia's political mis-calculus eventually strained the relationship between Nigeria and Ghana. How did the Aliens Compliance Order affect our relationship with the world? “The 1969 Order also affected Ghana's image in mainland Africa and the rest of the world,” writes Shirley Akrasih (See “Ghana Must Go: The History of Ghana's 1969 Aliens Compliance Order and Nigeria's 1983 Expulsion Order”).

On the other hand, the legal problematic of the Certificate of Emergency cannot be glossed over for political expedience. In 1971, among other things, the Certificate of Emergency was passed by the Busia administration establishing the outlawry of public display of Nkrumah's books, pictures, etc., following public reversion to singing of CPP songs by remnants of the banned CPP at the inauguration of the People's Popular Party (PPP), led by the radical laywer John Hansen, in Kumasi, as well as public demands on the Busia administration by the Ghana Union of Students (NUGS) that Nkrumah be "treated as an elder statesman, honored for his past achievements...and encouraged to live in retirement at home (See Roger Gocking's "The History of Ghana," p. 160; see subtitle "Losing Control of the Political Kingdom")." Gocking continues: "Busia felt threatened enough by these developments to warn publicly the pro-Nkrumahists against seeking to revive the CPP, and shortly afterword his government passed egislation making it a crime for anyone to promote by any means the restoration of the former president." Surprisingly, it took parliament a whopping 17 hours of deliberation to enact the Certificate of Emergency into law! Yet Busia ensconced himself in the public conscience as an avowed evangelist of democracy. Understandably, after the passage of this law prominent members of the Busia administration publicly went on record to demand that the heads of those caught with Nkrumah's pictures, books, etc., be shoved down the concrete throats of water closets.

Quite provocatively, the saintly paradox is that the West saw the political dispensations of Mobuto Sese Seko and KA Busia as symbols of democracy and those of Kwame Nkrumah and Nelson Mandela as symbols of authoritarianism. We should also point out that Busia rejected Nkrumah's formal request to come home to die after having being ravaged by skin cancer, a medical problem with possible epidemiological roots in the Kulungugu bombing. But Nkrumah's medical “skin cancer” would come to represent the political “skin cancer' of Ghana's underdevelopment! Thus, Busia's rejection raises a number of suspicious questions, including throwing away a golden opportunity to put Nkrumah on public trial for the alleged crimes his government committed. Such a trial, for instance, would have dealt with serious issues in which Nkrumah answered to the people of Ghana. Yet, we also do know for a fact that Nkrumah did not assassinate any of his political opponents, as the American political scientist Prof. Irving Markovitz has established (See “Ghana Without Nkrumah: The Winter of Discontent”), for, if the allegations against Nkrumah were true, even remotely, Busia and his government would have availed themselves of the opportunity.

In principle, this is a tenable theory but, again, understandably, was denied its legal testability in a court of law, because Busia and his government feared Nkrumah's living pictures, books, speeches, etc., not to talk of his physical presence, even if bedridden and ravaged by cancer cells! Surprisingly, more than four decades after his eventful passing not a single confirmable evidence has been adduced to support a political opponent assassinated by Nkrumah. Pointedly, Dennis Austin, author of “Ghana Observed: Essays on the Politics of a West African Republic,” has this to say about Busia: “Meanwhile those who had believed that Busia and Progress would be a considerable improvement over both the CPP and the military, as a party to defend 'Freedom and justice,' watched with some dismay the erosion of those high principles defended in Busia's own account of 'Africa in Search of Democracy.'”

In other words, Busia, a self-styled choragus of democracy, threw the democratic principles he had always espoused to the theoretical dogs of authoritarianism, as Austin forthrightly recounts in the afore-mentioned book, Busia's book, when the commodiously air-conditioned corridor of power suddenly assumed a political and social state of sweltering claustrophobic narrowness. Soon, it turned out, reality dawned on Busia that rhetorical democracy had no place in the boxing-ring of political actualities. He also realized that the commercial enterprise of bomb-throwing, running off at the mouth, and political terrorism did not solve society's problems. Instead, he realized that critical thinking, foresight, intellectual boldness, native intelligence, cosmopolitan appreciation of the world, and mastery of statecraft did! That begs the questions: Were Busia and the colonial government, represented by the Queen of England, more democratic than Nkrumah? Was the Queen of England not the leader of a one-party colony before the political advent of Nkrumah broke through the gridlock of queenly autocracy?

Also, was it not the political vision Nkrumah, like Mandela, who introduced electoral politics and multiparty politics in the body politic, the first of its kind in the history of the Gold Coast? Yet Busia and President Barack Obama have a lot in common: Forced deportations of “aliens” and abandonment of pre-presidential democratic beliefs upon resumption of political office. Illegal wiretapping or “certificate of emergency” (NSA and Edward Snowden), targeted drone assassinations (hunting down CPP sympathizers), support for authoritarian regimes (Busia and Apartheid South Africa v. Obama and Yoweri Museveni's Uganda), preventive detention (banning the CPP, driving CPP members into exile, and jailing some)! However, unlike Busia, Obama sold a clear head to the American people not on the cheap, hence making public statements with enough room for belated criticism. His slogan “Yes We Can” is an exemplary rhetorical device meant to court public sympathy for the national project of progressive politics, of nation-building. How? It does not say “Yes We Must!”

Then, why resort to unpopular subversion of popular sovereignty when the collective conscience of a well-informed, discerning people rejects the elitist philosophy of political novitiates, as happened in the case of Busia and Danquah, via terrorism, thereby killing innocent children, women, and men, and via clandestine collaborations with foreign intelligence agencies to topple a democratically constituted government? Why try to impose the “iron law of oligarchy,” a foreign product, on the people, as, again, Busia and Danquah, the CIA's, ADECE's, and M16's “Doyen of Gold Coast Politics,” did? How did Danquah, a mere political snippet, expect his elitist eschewal of the people, as told to Richard Wright, the American writer, by Danquah himself, an explosive snatch of historical information reported by Ama Biney, author of “Kwame Nkrumah Social and Political Thought,” translate to populist cuddle and electoral embracement? Yet, the reactionary politics of Busia and Danquah is, arguably, the rootage of today's rhetorical violence advanced by the cadet branch of the erstwhile National Liberation Movement, the first terrorist, Al-Qaeda-like, organization of its kind in Ghana's entire political history.

Even so, it is a worrying trend to see people uncritically embrace Western public self-identification with the core of democratic principles, with the West essentially seeing itself as a bastion of democracy, if you will, when most dictatorships around the globe are the direct or indirect making of the West, a view Prof. Noam Chomsky and several others have eloquently pointed out, more so because Western democracy is the political sire of Al-Qaeda and the Taliban, among others. As expected, the West, which has conveniently branded Kwame Nkrumah a dictator and Nelson Mandela a terrorist, is the same West that has described Mobuto Sese Seko as a “friend of democracy and freedom,” “a voice of good sense and good will,” and “one of our most valued friends on the entire continent of Africa (See Muritha Mutiga's piece “The Ugly Side of Ronald Reagan”; see also Antoine R. Lokongo's “DRA: Democracy at a Crossroads,” “Pambazuka News,” Nov. 16, 2011).” Sadly, even educated Africans have bought into this Platonic “noble lie.” That said, Ghana and Africa are confronted with a dilemmatic moral choice between Kwame Nkrumah, a spasmodic dictator, and Mobuto Sese Seko, a thoughtful democrat!

Meanwhile, what accounts for this high level of political inscience among Africa's ruling elites in particular and the masses in general? One of the major reasons is probably because Western policies, specifically foreign policies, are not sufficiently taught in African schools, for, if they were, Ghana and Africa would have charted separate developmental paths by now from the foreign policy hegemonies of the West, as regards matters of intra-African politics, development economics, environmentalism, and the like. Undeniably, socio-historical amnesia is part of the framework of institutional ignorance as well, a canker in the body politic. This canker is figuratively synonymous with Nkrumah's “skin cancer,” what Afrifa, Kotoka, Danquah, and Busia left for Ghana. It appears the body politic is suffering from this canker, this “skin cancer” of uncritical thinking by post-Nkrumah leadership. It also appears democracy itself has become a canker in the body politic.

That leads to another question: Does democracy exist in the Western world? Nothing of the sort exists! Actually, a wealth of evidence exists to the contrary, the existence of democracy. Democracy does, in fact, exist in the Western world if the question is about elections, with the masses hardly allowed participation in policy-making decisions at the national and international levels in post-election socialization between political elites and the masses. So, the existence of democracy in the Western world is an urban myth. “For many, the recent U.S. elections raised serious doubts about American system of democracy,” notes Richard Sanders, editor for “Press for Conversion,” adding: “However, millions of others around the world long ago abandoned any notion that the U.S. is a bastion of democracy, either at home or abroad. The U.S. government has, in fact, been a major opponent for millions of people around the world who have struggled to create and maintain democratic systems of governance (See “Just Say Know! The CIA's War on Democracy”; see also “A People's History: The Subversion of Democracy from Australia to Zaire”).

Ironically, this is no news! But how exactly has the American government employed the services of the CIA in its covert operations around the world? “Since WW11, the CIA has played a pivotal role in this history of subverting political systems. It has been active in virtually every country of the world and has conducted thousands of secret operations,” maintains Sanders, continuing: “As a tool of the U.S. president, the CIA has been used to manipulate, undermine and blatantly overthrow countless governments including dozens of functioning democracies.” Now, Sanders, however, directly responds to the afore-asked question, writing: “The CIA's history is filled with rigged elections, fraud, bribery, sabotage and economic warfare. CIA officials have masterminded psychological warfare, extensive propaganda and the spreading of lies and misinformation through the media…The CIA planned, armed and financed many military coups that consciously installed brutal regimes to better allow the pillaging of resources by U.S. business.”

It seems, therefore, that Western hegemonic interests are irrevocably tied to economics, which is a concept Nkrumah consistently harped on in his books and speeches. Also, Milton Allimadi, CEO and founding editor of the New York-based newspaper “Black Star News,” has revisited aspects of the central issues raised by Sanders (See “The Choice is Clear: Africa Must Embrace Nkrumah's Vision and United,” “Black Star News,” May 26, 2013). Admittedly, the invocation of bribery recalls a historical triumvirate matrix, a convoluted story pinnacled by CIA bribery of General Africa and Co., Nkrumah's overthrow, and CIA payments to Danquah's wife while he luxuriated in prison for attempting to overthrow the democratically elected government of Nkrumah. In fact, Prof. Noam Chomsky has even gone further, unraveling America's clandestine role in international terrorism, namely, covert activities either actualized through mercenary states or through client states, or both (See “International Terrorism: Image and Reality”).

On a different note, the CIA's role in Mandela's capture, a serious matter subjected to political tergiversation and intelligence cloudiness since his release in 1990, is not a close secret anymore (See Andrew Cockburn's “A Loophole in U.S. Sanctions Against Pretoria,” “The New York Times,” Oct. 13, 1986; “One of Our Greatest Coups: The CIA & The Capture of Nelson Mandela,” Democracy Now, Dec. 13, 2013). Thus, Ghana and Africa need to develop strategic, focused foreign policy to protect their geopolitical interests, including the protection of their progressive, forward-looking leaders from annihilation by foreign elements whose interests these African leaders do not represent. Nkrumah sufficiently addressed this very question (See “Nkrumah's Foreign Policy, 1958-1966,” the Chapter 9 of Ama Biney's book “The Political and Social Thought of Kwame Nkrumah”). Still, foreign policy decisions have instrumentalist thereness in world affairs subject to the moral constraint of relative self-autonomy, of continental unity (See Kofi K. Dompere's “African Union: Pan-African Analytical Foundations” and “Polyrthmicity: Foundation of African Philosophy”).

Yet, somewhat paradoxically, Nkrumah's progressive politics, his unstinted love for humanity, and his long-tunneled vision would constitute his downfall, while Busia's incompetence, ethnocracy, niggardly political vision, rhetorical shenanigans, and political demagoguery would precipitate his downfall. Danquah's political incompetence, deflated elitism, and narrow political focus were the major reasons his own people, the people of the Gold Coast, and the world at large rejected him. Certainly, the intellectual and political haplotype of Busia and Danquah is no match for the likes of Nkrumah, more so since their combined legacies do not technically offer Ghana and the African world any progressive ideas for national and continental development by way of development economics and Pan-African consciousness. This is because, among other things, the testudinate gait of post-Nkrumah Ghana's development is normatively ascribed by scholars to Nkrumah's overthrow, bad post-Nkrumah leadership, not to his foibles (See Robert Wood's “Third World to First World—By One Touch: Economic Repercussions of the Overthrow of Dr. Kwame Nkrumah). What do we do then? “When are we going to have visionary leaders in Africa?”, asked Honourable Saka, founding Pan-Africanist analyst of the Project Pan-African (PPA).

In fact, Saka's pointed question has bedeviled lay and scholarly minds alike. It is also a moral question to which Ghana's and Africa's post-Nkrumah leadership has woefully failed to tackle—if at all. But the question itself is a storied one at that! And it involves the moral assassination of the “African Dream,” the kind of noble positive ideas dreamt by visionary thinkers such as Kwame Nkrumah, Bob Marley, Marcus Garvey, and Patrice Lumumba. Saka addresses this question through a poignant negation of self-serving alibis for the middling or subpar performance of Ghana's and Africa's post-Nkrumah leadership. He writes thus: “After 50 years of our flag independence, almost every single project that could potentially bring relief to the African people has either been abandoned or being held in the pipeline. Thanks to the IMF-imposed policies. Our local oil refineries have been forced to shut down operations. Our leaders therefore ship the raw crude to European refineries after which the refined product is imported back to Africa.” Was this the kind of world Nkrumah intended for Africa? Again, regrettably, this is the bleeding world the Duvaliers, KA Busia, Akwasi Afrifa, Jean-Bédel Bokassa, Mobuto Sese Seko, JB Danquah, Omar Bongo, and Emmanuel Kotoka bequeathed to their unsuspecting posterity.

Saka, however, continues: “Many of the factories which were built in Africa to process the bauxite, the copper and other strategic resources have been forced by IMF-imposed policies to shut down and left to rot. For many years, Africa has remained the producer of raw material and the dumping ground of European, American and Chinese products (See Saka's “Where is the African Dream?”, published on the website of “The Doctor's Report,” Feb. 23, 2013).” The immediate question to ask is: Where are Nkrumah's Tarkwa Gold Refinery and Tema Oil Refinery? They have assumed a state of rustic wobble in the frozen mental age of African leadership. Then again, regarding Busia's dictatorial proclivities, Austin captures this tidal rhythm of Ghana's political history when he wrote of Busia: “They did not like the harsh and summary expulsion of non-Ghanaians, nor the Bill (again under a certificate of emergency) to forbid the advocacy of 'Nkrumahism,' nor the proposal to Protect the Prime Minister by legislation 'from insults,' nor the brushing aside of General Ocran's insistence that MPs ought to delay over complying with constitutional requirement to declare their assets, nor the rough handling of the dismissed civil servants, the universities, the judges, the opposition press, and the TUC (Ibid: 160).”

Suddenly, Busia, it appeared, had resolved into Ninkasi, an “autocratic” goddess of beer, in the lotusland of democracy! Then, his white-livered partner, Danquah, on the other hand, a man who reportedly wept like a misguided poltergeist of a stillborn fetus following his immurement with Ako Adjei, Akuffo-Addo, Nkrumah, Jones Wlliam Ofori-Att, and Obetsebi Lamptey by the colonial authorities, during the February 28, 1948 public agitations, which saw the deaths of Sgt. Adjetey, Private Odartey-Lamptey, and Cpl. Attipoe, supposedly, could not even execute a successful putschism against the politically intrenched Nkrumah, his political and intellectual nemesis, with the aid of the CIA and other subversive scapegraces, only for the former to turn around and recruit General Akwasi Afrifa and others to do the job. What happened to Danquah's “selfless politics” and “sacrificing one's self totality for one's own country”? Was Danquah, a political paedomorph, as it were, truly a ritual murderer, as some have claimed?

We shall return…

Akufo-Addo’s govt is the ‘biggest political scam’ in Ghana’s history – Mahama ja...

Akufo-Addo’s govt is the ‘biggest political scam’ in Ghana’s history – Mahama ja...

Performance Tracker is not evidence-based — Mahama

Performance Tracker is not evidence-based — Mahama

Four arrested for allegedly stealing EC laptops caged

Four arrested for allegedly stealing EC laptops caged

$360 million IMF bailout not enough for Ghana – UGBS Professor

$360 million IMF bailout not enough for Ghana – UGBS Professor

Shrinking Penis Allegations: Victim referred to trauma hospital due to severity ...

Shrinking Penis Allegations: Victim referred to trauma hospital due to severity ...

Adu Boahen Murder: Case adjourned to May 9

Adu Boahen Murder: Case adjourned to May 9

‘I've health issues so I want to leave quietly and endure my pain’ — Joe Wise ex...

‘I've health issues so I want to leave quietly and endure my pain’ — Joe Wise ex...

Let’s help seek second independence for Ghana before NPP sells the country – Law...

Let’s help seek second independence for Ghana before NPP sells the country – Law...

New Force aims to redeem Ghana and West Africa — Nana Kwame Bediako

New Force aims to redeem Ghana and West Africa — Nana Kwame Bediako

‘I didn't say I would buy Ghana if voted against; I said I’ll buy it back from f...

‘I didn't say I would buy Ghana if voted against; I said I’ll buy it back from f...