The memes on the African Child

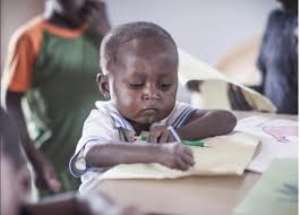

There have been a lot of jokes flying around recently. In this Information Age, in this social media era of ours where delusion, misrepresentations, lies, are sold around rampantly. There is one truth circulating around, albeit in a form you would not expect. In jest—memes, in funny video clips. The joke regards the Ghanaian child.

See, we have been told that witches in the spiritual realm walk upside down. Does it make sense what I just wrote? I meant, the rumours that went around—at least, when I was a child—was that witches walk with their heads, with their feet left dangling up above—where their heads ought to be. That paints quite a picture. But somewhere in Africa, a young girl implicated herself in this myth. “My head, my shoulders, my knees, my toes!” she sings—she is serious. And you already know this: “My head”—she points to her feet. “My shoulders”—points to her knees; “my knees”—to her stomach. “My toes”—the poor child points to her head. And don’t forget— “It all belongs to Jesus!”

What of the young boy who, from all indications, knew he was being made the butt of the joke: “Meko – Onion, amango – sugarcane, edua – banana, kosua – apple, nantwinam – plantain (and oh! he changes his mind)—Kalyppo” he sings a game of word association.

Or that child who when asked in an examination to use the pronouns ‘him’ and ‘her’ in a sentence wrote something in the line of—and I don’t remember precisely but it went—“Obiara him no handkerchief” and “Her! Ama where are you going?”

I knew a lady who spoke of a neighbour’s child. The young boy when asked “Kwaku, what do you want to be in the future” would reply, “Mey3 ashawo”—I want to be a prostitute.

Thinking through the Laughter

It is good that society can laugh at itself. But as we are laughing, work ought to be underway to right these wrongs. Corrections must be in motion to reverse our flawed reality. This reality where the Ghanaian child has their knees deep in poverty; quality education denied them. This reality where the things the adult population find funny about the Ghanaian child is not their intrinsic childishness—typical of children, that makes for good adult viewing—but rather, their ignorance.

A child does not know better—that is a biological, better still, a sociological fact; one which can never be reversed. But when a large number of our children are denied those basic necessities owing a child—case in point: quality education, any humour we squeeze out of their existence cannot be satire. It cannot be satire if quick and effective steps are not being put in place to remedy this ill—this very damning societal ill clothed in jokes. It is plain derision—just good old mockery. And I don’t think that is the picture the Ghanaian or African adult population intends to paint with their laughter. You and I are not laughing at that Ghanaian child, but laughing at the situation. Are we not?

You and I are not advocating that they keep the jokes coming—whoever the ‘they’ are—are we? When you and I, sitting in the comfort of our homes, after a long day’s work, skimming through our phones, fingers crossed waiting on one of these memes to come our way, actually get hold on such funny clips and immediately share them, we do not do so to mock those children, do we? When we, keeling over with laughter, call our wives, husbands, colleagues, children, parents, to “come and watch this” and show them these video clips and memes of the Ghanaian/African child putting their ignorance (not justified for their age) on display, we do not intend to break their spirit. No, we certainly do not.

Nonsense

Somewhere early last year, I read an article—a ‘research’ article apparently (sarcasm intended)—undertaken by a certain prominent institution (name withheld) that made the argument for a Diasporan-led (or assisted) African development. The article was done in good faith, I will not deny it that. But what one realises, reading between the generic lines—the very generic argument that article was making in favour of the Diaspora, one sees that the writers, suffer, perhaps, the same Stockholm syndrome a large chunk of us, Africans suffer. Even the best of us, suffer this syndrome intermittently—at least.

The writers sought to expound the benefits the African Diaspora can offer to the African continent—a proposition many of us will not argue against. After all, isn’t this exactly what our Year of Return clarion call was about? We may, however, argue against the reasoning behind the proposition, not the proposition itself. But this is a topic for another day—a topic I will endeavour to dissect elsewhere, perhaps.

Long story short, the research paper claimed that one of the key things that drive Ghanaian parents to move heaven and earth to get quality education for their children is just so that these children of theirs can get opportunities to study abroad. That this same dream of studying and living abroad—in the developed world, in the OECD countries—is why these kids try their hardest in school.

Now, I do not know which Ghanaian child you have ever been acquainted with. Neither do I know which Ghanaian parent you have ever been acquainted with. But all I know is that we have all been Ghanaian children ourselves; that we have, in so doing, known many a Ghanaian child. So, we have a very deep understanding of what this much mentioned ‘Ghanaian child’ is.

I know that some of us have been Ghanaian parents—or that we have known many Ghanaian parents. Hence, we know what the Ghanaian is intimately enough—more so than these foreigners sitting somewhere in their developed countries, with some graphs and figures as their main reference points.

That being established, I can boldly state that this assertion by the above-noted research paper is far from the truth.

Who’s Laughing Now

The Ghanaian child, for the most part, dreams within their confinements. I use ‘confinements’ here for lack of a better word. Because ‘confinement’ used in this context sounds bad, does it not? But I do not mean it bad at all. I mean the Ghanaian child may dream of being the world’s greatest, but it does not necessarily entail leaving home, leaving Ghana—so they can be what they want to be. They will bluntly state: I want to be President, lawyer, doctor, soldier, etc. But the Ghanaian child will not list migrating to a developed country as, in itself, an aspiration. They do not wake up, and excitingly march on to school—no matter how rickety these schools are—just so they can get the opportunity of traveling to America someday.

Parents do not sweat it out, sweat blood to put their children through school just so these kids can travel to London one day. The opportunity of traveling far and wide is just a by-product, if anything at all, not an end in itself.

I have come to know this as truth: the poor Ghanaian child carries a ‘Double consciousness’. They dream wildly, but are aware of the inherent limitations their upbringings present—the lack of quality education, having to take on a trade to supplement the family’s income, the struggle to attain the most basic of needs and amenities—food, clothing, shelter, electricity, quality healthcare, potable drinking water, etc. They are aware of how disadvantaged they are in this very highly competitive world. So, they dream wildly, but speak modestly.

I have met many a Ghanaian child who when asked of their aspirations will say something like: “I want to be a fitter,” (‘fitter’ with that Ghanaian connotation) but when queried to speak their truth would say, “I want to be an engineer.”

So, the next time you and I get hold of these funny clips, these memes; when laughing, we must do so knowing that the joke is on us. That the Ghanaian child know we wouldn’t be able to handle their truths. That we, beaten badly by life, will only sneer at their unblemished childlike wonder—so they best hide them from us.

That kid knows she wants to be President someday, but she will tell you, “I want to be a borlawoman,’ so you can have your laugh.

Tomorrow, 20th November, is World’s Children Day. Happy World’s Chi—oh! I’m too tired to do this.

BY YAO AFRA YAO

This IMANI job no dey pap; the people you are fighting for are always fighting y...

This IMANI job no dey pap; the people you are fighting for are always fighting y...

Prof. Naana Opoku-Agyemang has changed; you can see a certain sense of urgency –...

Prof. Naana Opoku-Agyemang has changed; you can see a certain sense of urgency –...

MFWA Executive Director slams Akoma FM for engaging in ‘irresponsible’ media pra...

MFWA Executive Director slams Akoma FM for engaging in ‘irresponsible’ media pra...

‘Women must become millionaires too’ — Prof Jane Naana on establishment of Women...

‘Women must become millionaires too’ — Prof Jane Naana on establishment of Women...

Some believe only in Ghanaian votes, not Ghana — Kofi Asare jabs politicians

Some believe only in Ghanaian votes, not Ghana — Kofi Asare jabs politicians

Plan to make BEST sole aggregator of Sentuo Oil Refinery will create market chal...

Plan to make BEST sole aggregator of Sentuo Oil Refinery will create market chal...

2024 elections: I can't have the man I removed from office as my successor — Aku...

2024 elections: I can't have the man I removed from office as my successor — Aku...

2024 Elections: Immediate-past NPP Germany Branch Chairman garners massive votes...

2024 Elections: Immediate-past NPP Germany Branch Chairman garners massive votes...

Gov’t focused on making Ghana energy self-sufficient, eco-friendly – Akufo-Addo

Gov’t focused on making Ghana energy self-sufficient, eco-friendly – Akufo-Addo

April 25: Cedi sells at GHS13.74 to $1, GHS13.14 on BoG interbank

April 25: Cedi sells at GHS13.74 to $1, GHS13.14 on BoG interbank