Recently, there have been a lot of conferences, debates, points, and counterpoints, in and outside Ghana, all aimed at addressing that seemingly intractable problem of the Ghanaian economy's industrialization deficit. In particular, the debates have attempted to address the question of how we can jumpstart our march to the heights of technical sophistication. Perhaps the tenor of the debate can best be captured by a statement made recently by Ghanaian journalist and Managing Editor of the 'Insight Newspaper,' Kwesi Pratt, to the effect that the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology (KNUST) is unable to produce solar panels fifty years after it was founded.

As might be expected, the provocative nature of Kwesi Pratt's statement engendered a firm response from a Senior Lecturer at KNUST, Richard Tia. His response, as reported in the March 16, 2018, issue of Ghanaweb, was that “the way the university is set up, it is almost impossible for the institution to be the driving force of the setting up of companies.” He continued: “So we train the students, endow them with technical know-how and send them into the world. What happens there is a function of the business environment of the country…” Ironically, both Kwesi Pratt and the Lecturer, Richard Tia are correct in their assessment that KNUST, and by implication, all of Ghana's science and technology institutions, Universities, and Polytechnics, do not seem to have played the role of 'prime mover' for Ghana's industrialization. Where they appear to disagree is why this is the case.

To fully appreciate why KNUST, and other Ghanaian Science and Technology Institutions find themselves in this position, one needs only take a cursory look at the history of engineering education as it came into being in Ghana. The fact of the matter is that KNUST, starting out around 1951 as the Kumasi College of Technology (KCT), was not founded, by the Colonial Government, with the intention of having it become the driving force behind the industrialization of the Gold Coast. As with most of Ghana's educational institutions going as far back as the establishment of Secondary Schools, the objective of the colonial administrators was to produce professionals for the civil service. This policy would ensure that the institutions needed to administer the country could be run by Africans, where possible, to reduce the number of European Civil Service personnel that were necessary to be sent to the colonies. This action was desirable from an economic standpoint. For, African labor at all levels was cheaper than the European one, not counting additional costs such as trips back to Britain every couple of years or so for the British employees and their families. Founding a university that would be the dynamic engine for the creation of an industrial base in the then Gold Coast was, we suspect, the furthest from the minds of the founders of KCT. When Ghana attained independence in 1957, the nation, unfortunately, made no conscious effort to reorient KCT, later to become KNUST, to such a new mission, of expecting the technology institution to directly, not indirectly, power Ghana's industrial development.

The objective then, stated or unstated of KCT (later KNUST), was to produce technical administrators for organizations such as the Public Works Department (PWD), the Railways, the Municipal Bus systems and other governmental institutions requiring some level of technical knowledge. Such knowledge was to be used mostly for administrative purposes rather than in the role of transforming the Gold Coast or Ghana into an industrial powerhouse. Indeed, it was not uncommon for the term "engineer" to be understood or more correctly, misunderstood during colonial times and long after that, as nothing more than a glorified mechanic. Locomotive drivers were called engineers and the engineering profession at the time, if we may call it that, was seen as characterized by greasy shirts and oily fingers. That was what "engineers" meant to large swaths of the public. In any case, “mechanic-type” jobs, even if albeit, in a supervisory role, were mostly the career choices open to graduates of Kumasi College of Technology and subsequently, KNUST, at least in the immediate aftermath of independence and several years after that. These engineers were not expected, nor was it demanded of them consciously or unconsciously by their employers and society as a whole, to carry out research or invent, as well as manufacture and market new machinery, devices, systems, and products. Even if they were, there were no opportunities in the country for such careers. As an example of this, when one of us visited the GIHOC plant that was assembling Sanyo electronic products in the early 1970s and suggested that the printed circuit boards could easily be made locally, he was informed that the agreement with Sanyo precluded such local efforts.

Indeed, a massive culprit in this area was our initial emphasis on import substitution industrialization. This plan was implemented most often, by merely buying factories and the finished technology for their end products from overseas. These factories very often came with agreements that precluded us from redesigning, improving or manufacturing the components locally as we found at Sanyo. The idea, too often, was to prevent the technology transfer in any form to the local scientists and engineers. Indeed, another eye-opening experience at the Firestone Tire plant at Bonsaso in the 1970s captured this point entirely. There were Ghanaian chemists on the staff, but the selection of the specific chemical ingredients and the amounts needed to produce the galvanized rubber was controlled and never shared with the Ghanaian chemists. We suspect we are still unable to make tires from scratch after all that investment. It is doubtful this situation of foreign entities deliberately hiding technical knowledge from our engineers and scientists has changed very much all these years later. And sadly, very often, it is our own signed agreements that have contributed to this.

It should be noted that the situation in Ghana contrasts sharply with what obtains in other countries where some engineers go straight from the classroom to set up industrial start-ups to power the economy. A few example situations are to be noted. Direct industrial start-ups by students and graduates in science and technology from the University of California, Berkeley, Stanford University, University of Santa Clara, California State University at San Jose, are what created, arguably, the most significant techno-business area called 'Silicon Valley.' Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), Harvard University and other Boston institutions directly built up the techno-business powerhouse of Massachusetts' economic miracle and its electronics highway (Route 128). Duke University and the University of North Carolina and North Carolina State University created the Research Triangle Park. The science and technological might of the Universities of Michigan, Illinois, Minnesota, Purdue, Michigan State, Penn State built the economic and industrial Midwest of the United States. In all these cases, developments in science and technology by the students and teachers directly went from classroom and laboratories to product and manufacturing start-ups. The University of Arizona and Arizona State University built the 'Silicon Desert' of Arizona. All these industrial parks were encouraged and subsidized by governmental agencies at the local or state level, and the initial funding was provided by venture capital.

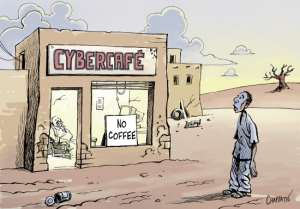

This low level of direct impact on Ghana's industrialization by KNUST, it must be stated, in no way reflected on the intellectual caliber of the graduates of KCT or subsequently of KNUST or the other technical institutions. One of us was privileged to have been a member of the Faculty of Engineering at one point after graduating from a well-known university in the United States. He was astounded by the difficulty (high caliber) of the course material that the students were required to master compared to his own and realized that these students were among some of the most brilliant engineering students in the world, including students at some of the more famous universities in the United States. But he also felt a sense of sadness for most of these KNUST students, because he knew from the jobs available to them upon graduation, that with the possible exception of the graduates of the Civil Engineering program, most of them would be graduating and moving on to a technological desert. Civil engineering is a field where it is easier to practice the theoretical and practical arts of engineering almost straight out of school. Usually, all the tools needed to design a road or a bridge are readily available. Working out the structural loads on a building can be done using the knowledge acquired at KNUST and in this regard, the most successful practitioners of the science of engineering as taught at KNUST, are probably the civil engineering graduates. It is, therefore, not surprising that KNUST trained civil engineers, generally speaking, tend to flourish in the Ghanaian technology environment, positive proof if any is needed, that given the right situation, KNUST graduates are up to the task of applying their skills to the betterment of Ghana. Unfortunately, this positive environment does not exist for several of the other areas of engineering.

Imagine the prospects for satisfying employment of a KNUST graduate in aeronautical engineering. On the other side of the Atlantic, her possibly less accomplished counterpart, upon graduation from perhaps a less demanding university, might enter the workforce at Boeing Aircraft and under the tutelage of experienced engineers end up designing the next generation of commercial aircraft. The KNUST-trained Ghanaian counterpart, on the other hand, may at best end up being the supervisor of this aircraft's maintenance crew at Kotoka Airport, most of her aeronautical design knowledge having atrophied. This situation is what the lecturer was referring to when he said: "So we train the students, endow them with technical know-how and send them into the world. What happens there is then a function of the business environment of the country…" In this regard, the lecturer is correct, as things stand in Ghana right now. It is this missing link between an existing industrial base that takes KNUST's graduates and moves them on to the next level of technical sophistication that has been hampering the growth of a sophisticated technology base in Ghana all these years. It is, in short, a question of the chicken and the egg. And so, if Kwesi Pratt sees no aircraft (or solar panels) coming off the assembly lines in Ghana or new industries sprouting like mushrooms in vibrant industrial parks, he also has every right to ask what on earth is going on. As engineers and technologists, we can't just blow him away. The country has invested vast amounts in our education, and we owe him an answer.

Having spent a combined approximately seventy years in academia and industry in the United States, we believe we have some insights regarding this issue of the role of academia in industrialization that we would like to put out here for consideration. At the risk of repeating ourselves, the fundamental problem is that we, unlike the industrialized West, do not have the industrial base to enhance further the knowledge acquired by our engineering students in class in industrial design and manufacturing. Hence, upon graduation, they end up roaming, in too many cases, a technology desert with no green shoots of industrial progress for our country to show for her investment. It seems, therefore, to us that what we need to do is find innovative ways to close this gap.

We, therefore, propose the creation of a National Design and Manufacturing Center (NDMC) as a sort of postgraduate practical training university to enhance the industrial design and manufacturing skills of our recent graduates. This knowledge enhancement should, ordinarily, be done routinely by Ghanaian industry if it existed in the appropriate size and quality which unfortunately it does not. The instructors at the NDMC would not necessarily be limited only to a 'Regular Academic Faculty'. Instructors at these Centers would also include engineers who have spent large portions of their professional lives designing and manufacturing products, devices, and systems and we would hire them from around the world, although Ghanaians would be preferred. Some of the instructors could be one or two-year 'Visiting Industrial Fellows.' Every graduate of our engineering schools would be entitled to a one-year residence at this facility with the sole objective of turning their final year project into a functioning prototype, and potentially a commercial product if they so desire. Non-university graduates who come up with novel ideas may also be selected to attend the NDMC, after a rigorous review of their inventions or innovative ideas. This center would come equipped with most of the tools needed to manufacture an engineering design: equipment such as 3D printers, 5-axis milling machines, CNC machinery and plastic molding machinery plus others, all having been selected by this team of manufacturing experts. Training on the use of these machines would be part of the curriculum for students at our Technical schools. The NDMC would also include laboratories for design and manufacturing of light electronic and electrical products. Also, the NDMC would be surrounded by a pre-developed industrial park, meaning that roads, electricity, water and all necessary infrastructure would be in place to make the setting up of small-scale factories to produce these items a relatively pain-free process. Having the experts close by as potential advisers should also improve the chances of success for these new industrial ventures.

Alternatively, a few of Ghana's Science and Technology Universities could be selected to house “National Design and Manufacturing Centers” (NDMCs). The idea is like establishing “Centers of Excellence” at say, five Science and Technology Universities or Polytechnics. The NDMC(s) could be standalone institution(s) or affiliated with the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR).

The students' final year projects would have been selected and approved based on being new inventions or technologies, or old ones such as solar panels, that government has identified as being of national importance. These projects, rather than being “toys” as they most likely are now, completed and left on the shelf to gather dust, would be subjected to stringent engineering and economic feasibility analysis on an ongoing basis during the years the student is developing these in college. As with all manufacturing plants, the students would need to match their final year designs to the tools and machinery available at the NDMC, and this would be part of the design review for their project. This proposal doesn't end here though. Additionally, government would partner with or encourage the private sector, through tax deferrals and other incentives, to be heavily involved on an on-going basis with these students. The ultimate goal will be to fund the scaled-up manufacturing of these items if they pass the necessary engineering and economic feasibility tests. We suspect some foreign foundations or corporations might be interested in participating in and supporting this venture. Over time, the graduates of this Center would form the core of an industrial renaissance in Ghana that could propel us forward. Perhaps in twenty-five or thirty years' time, with the successful industrialization of Ghana, there might be no further need for such Centers at which point we could turn them gradually into Centers for Advanced Design and Manufacturing Research.

It takes more than just engineering know-how to create a successful business. We would expect the students at the various business schools in the universities to partner with the engineers in the form of a business development team. They would be responsible for conducting market analysis and must be prepared to present a business plan to the venture capitalists recruited by government, also as part of their graduation requirements. They would be partners in any businesses formed out of this collaboration if they wish. The NDMC would have very strict milestones and would be monitored and assessed by a combination of Ghanaian and internationally recognized institutions. This strict supervision would encourage transparency of operation and ensure sound budgeting and resource utilization.

We realize that all this takes us to a place we have never been before and has numerous risks attached to it, but also massive positive potential on the upside. But Ghana appears not to have much choice. Successive Ghanaian leaders have all expressed the urgency of “Ghana's need for technology innovation for accelerated growth and development.” The power of science and technology for national development was most emphatically stated by none other than the late Professor Francis Kofi Allotey, perhaps Ghana's most famous Scientist, Mathematician, and Technologist. As an invited speaker in 2015 at a conference held at Kumasi Polytechnic, Professor Allotey is quoted as having said:

“Science and Technology are now regarded as an international currency upon which fortunes of nations will rise and fall. However, the developing countries of today are slowly waking up to the realization that in the final analysis, creation, mastery, utilization of modern science and technology is basically what distinguished the industrialized/developed nations from the developing countries”.

And when it comes to the value of risk-taking by nations to achieve lofty goals, former U.S. President, Late John F. Kennedy said it best:

“we choose to go to the moon, not because it is easy, but because it is hard.”

Unless we are willing to take risks and do hard things, we'll be stuck here on earth, figuratively speaking, while, other nations blast past the moon and on to the outer reaches of the universe.

Joseph O. Cruickshank, Ph.D.

Consulting Engineer, Aerodynamics

A.O. Ebo Richardson, Ph.D.

Professor Emeritus, Electrical & Computer Engineering

April 23: Cedi sells at GHS13.66 to $1, GHS13.07 on BoG interbank

April 23: Cedi sells at GHS13.66 to $1, GHS13.07 on BoG interbank

GRA clarifies tax status of resident individuals earning income abroad

GRA clarifies tax status of resident individuals earning income abroad

2024 elections: NDC to officially unveil Jane Opoku-Agyemang as running mate tom...

2024 elections: NDC to officially unveil Jane Opoku-Agyemang as running mate tom...

Bawumia embarks on working visit to Italy and the Vatican to boost bilateral tie...

Bawumia embarks on working visit to Italy and the Vatican to boost bilateral tie...

Senegal's new leader calls for a rethink of the country's relationship with the ...

Senegal's new leader calls for a rethink of the country's relationship with the ...

Chairman Kingsley Owusu Brobbey calls for Privatization of Electricity

Chairman Kingsley Owusu Brobbey calls for Privatization of Electricity

Gov't to consolidate cash waterfall revenue collection accounts

Gov't to consolidate cash waterfall revenue collection accounts

Gov't to settle lump sum for retired teachers by April 27

Gov't to settle lump sum for retired teachers by April 27

Former PPA CEO granted GH₵4million bail

Former PPA CEO granted GH₵4million bail

NPP trying to bribe us but we‘ll not trade our integrity on the altar of corrupt...

NPP trying to bribe us but we‘ll not trade our integrity on the altar of corrupt...