This article is dedicated to all those Ghanaians who went to Nigeria in search of a better life between 1978 and the second “Ghana Must Go” in 1985. You saw the very best of Nigeria and no matter what happened to you then, or later, you will never forget your time in that country!

Some people say it was the “constro” boys who went first and came back home with the good news. Others say it was the trained teachers (Cert A holders) who went first, started teaching in secondary schools there and came back on holidays and took along their brothers and friends who are graduates. Still others maintain that Ghanaians had been travelling to Nigeria since goodness knows when. There were vehicles that made the long journey from Kumasi or Accra to Lagos. Long before our independence, Anlo fishermen and traders piled themselves into trucks setting forth from Keta into the wilds of Nigeria. The journey took the whole day. Nigeria was far away, very far away indeed.

No matter where the truth lies, one thing is certain. The great movement of Ghanaians to Nigeria in search of a better life would not happen until after 1975. Prior to that, nobody left Ghana to settle in Nigeria because Ghana was not good enough for him. There have always been ties between individual Ghanaians and Nigerians with inter-marriages meaning some Ghanaians moved to settle in Nigeria. But nobody left Ghana to escape economic hardships. Not until the mid-70s.

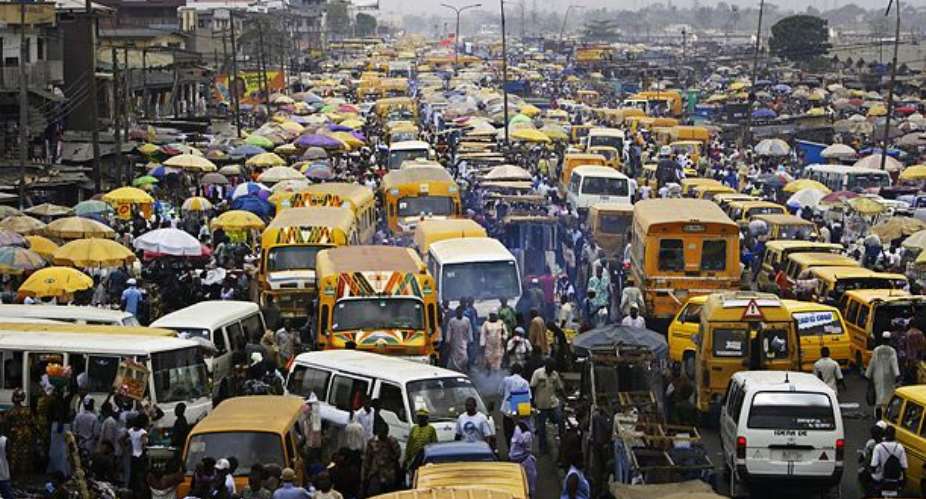

The largest chunk of the economic migrants from Ghana to Nigeria made their moves between 1978 and 1981 or thereabouts. By 1982, Lagos was full of Ghanaians from all walks of life. They ranged from university lecturers (and students), medical officers, political refugees, through secondary school teachers to our boys working on construction sites and our girls selling bread in the “go slow” on the highway leading out of Lagos to Abeokuta. They rushed to the slow moving vehicles peddling what they called “Ghana bread”. (Some of the Yoruba didn't like this bread complaining that there was too much sugar in it. Yes, much of Ghanaian bread contains too much sugar. If there is not too much sugar, then there is too much salt!) Some of our girls chose the easy way out and betook themselves to the houses of ill-repute where they plied their damnable trade.

By the 70s, the journey now took only a few hours from Accra to Lagos. If you liked, you made the “short-short” one by taking a vehicle to Aflao, crossing the border on foot, taking a taxi to the station near Asigame (Grand Marché) in Lomé, where you took one of the Peugeot “caravans” straight to the Badagry border where another vehicle took you into Lagos. You could also take a vehicle from Cotonou and make it to the old port of Porto Novo (Xogbonu) and enter Nigeria at Idiroko which was the border crossing before the huge Badagry border was rebuilt as the main entry point. The Idiroko to Lagos road was still called the “Old Ghana Road” when we were there.

For the Ghanaian making the journey by road to Lagos for the first time, it was a real experience. Once you cleared the Badagry border and was on your way on the dual carriage to Lagos, you knew you were somewhere far away from Accra. Lagos looked big to you. Much of it was like a huge construction site. This was the time when foreign companies like Julius Berger were building flyovers, overhead bridges, and motorways all over the place.

Even though Ghanaians could be found in every state, most of them were in the Yoruba speaking states which are geographically nearest to Ghana. The Yoruba are one of the largest of Nigeria's more than 250 ethnic groups. There are far more Yoruba than there are Ghanaians of all tribes worldwide! Most of the Nigerians who lived among us in Ghana before the Aliens Compliance Order (ACO) were Yoruba. They were the ones we called Alatafuo or Anago and when we went to them, they also called us Omo Ghana (no offence meant, none was taken either). So the Ghanaian connection with the Yoruba, in particular, is a long one. Some versions of Ewe history even trace the origins of the Ewe to a place called Ketu in Yorubaland. In the early 80s, in places like Ogbomosho, Ejigbo, Osogbo, Ilesha, one could still meet those Yoruba who had lived in Ghana before ACO and who still spoke fluent Twi, Fante, Ewe or Ga. They were proud to display their knowledge of these languages, having quite put behind them the bitterness that surrounded their painful and sudden departure (the munko munko or ACO) from Ghana.

The years around 1980 marked the most dizzying heights of Nigeria's oil-fired economy. The oil money was flowing through everybody's fingers and some of us were there to partake of the goodies. They accepted us so long as there was something for everybody.

Every Ghanaian who went there got some kind of job. Teachers were in high demand. It was very easy for the Ghanaian teacher to fit into the Nigerian classroom. Because WAEC gave us all the same GCE syllabus, Ghanaian teachers found themselves teaching exactly the same things they were teaching in Ghana. Maths, Science and English teachers were especially in high demand. The greatest need for teachers was in the states controlled by the UPN which were implementing free education – the type Akufo-Addo is promising us. The UPN was then led by Chief Obafemi Awolowo, the revered Yoruba leader. (I have, sometimes, wondered if there is some resemblance between him and Akufo-Addo that goes beyond their old style round metal-rimmed glasses.) Secondary schools were built in all towns and villages and students went straight from primary school to these schools without any exams.

It was not that there were no Nigerians who could teach their children. The economy was so good that Nigerian university graduates looked down on the teaching job. They easily got higher paying jobs in industry or obtained generous state or federal government scholarships to pursue advanced studies in foreign universities. Ghanaians readily took their places and acquitted themselves well. Indeed, there will come a time, (if that time is not even now) when a crop of prominent Nigerians can proudly say that some of their best teachers in secondary school were Ghanaians. They will be referring to that time, around the 80s, when so many Ghanaians taught so many Nigerians.

Everything was very cheap in this country. What we had then called “essential commodities” in Ghana were anything but essential in Agege (the name of the Lagos suburb that, in Ghana, became used for the entire country). Blue Band Margarine, which had ceased to exist in Ghana, was available at every roadside seller's. Beer was one naira for the premier brands of Star and Gulder – brands that we had known from Ghana. The big bottle of Guinness, Odekun, (which was unavailable in Ghana) went for 1.30 naira and the little bottle (kekere) made you poorer by a mere 70 kobo. Semovita cost 80 kobo a kilo. We did not even have Semovita in Ghana then. Sardines and Geisha (which Nigerians looked down upon but were favourite items in Ghana, the lack of which can cause governments to be overthrown) were all over the place selling cheaply. During the Christmas season, imports were increased bringing down the prices of items across the board. In Ghana price increases were particularly notable during the Christmas season.

Those Ghanaians who went to Nigeria before 1980 saw the very best of the country, economically. In some states, graduate teachers were given car loans in cash! You took your 3,000 naira, went to a car dealer and drove away with your brand new locally assembled VW “beetul”. It cost you less than 3,000 naira so you had something left over to buy petrol and drinks to celebrate your first new car with your friends – to “wash” the car, as it were. In the early 80s, a graduate teacher's monthly pay of 360 naira was enough to buy you a return ticket to the UK. That was before the Thatcher government brought in visa requirements for Ghanaians and Nigerians. Those Ghanaians daring enough went on holidays in Britain. The naira was equivalent to the pound and fetched you more than a dollar!

This was also the time Ghanaians would tell jokes about the newcomer who went to the wayside chop bar and asked for 50 kobo rice and 50 kobo meat and the seller woman looked at him with surprise. He insisted on his order and when he was served, there was no way he, alone, could eat it all that much food. He thought the naira was like the cedi he had left behind in Ghana.

At the beginning of each academic year, the now defunct West Africa Magazine published long lists of Nigerian scholarship winners who would be going to universities in Europe and North America to study obscure subjects in the sciences and technology. It was as if the states were competing with each other to see which of them could send the greatest numbers of their citizens on scholarships abroad. And each year, we would look at these lists with a tinge of envy. Our country could not afford to give us similar privileges.

The daily newspapers were bumper affairs of 48-60 pages at a time when our flagship national daily, Daily Graphic, was still running 16 pages in tiny print. There were even broadsheets, something we had never seen in Ghana before. A few of the numerous newspapers really had quality stuff. The newly established Lagos Guardian attracted articles from some of the country's greatest brains – Wolé Soyinka, Niyi Osundare, Kole Omotoso, Chinweinzu. Then came the newsmagazine, Newswatch, modelled on Time Magazine and better than anything we ever had in Ghana. On its staff were some of the country's best journalists including Dele Giwa who was murdered by a mail bomb during Babangida's reign of terror. There were several television and radio stations at a time when Ghana still had only one television channel and one national broadcaster and we had never heard of FM broadcasting. Naija movies were not available then.

The Ghanaian immigrant felt completely at home. Ghana was not too far away and you could visit home for the weekend. We settled. We started enjoying the food, the beer, the women and the music. Oh, the music, especially Yoruba music. Because of Juju music's roots in highlife, it was easy for Ghanaians to take on and like that music. Moreover, some of us still remembered the time when the Yoruba lived among us in Ghana and played lots of the music of the accordion playing I. K. Dairo. They may have played the music of Haruna Ishola too.

The 80s marked the heights of the careers of King Sunny Adé with his velvety voice (Gboromiro; Synchrooo ... synchro system) and “Shief” Commander Ebenezer Obey and his evergreen, forever and forever wedding song: Eto gbeyawo laye t'Oba Oluwa mi file le, pelu aseni... (What God has joined togedaa let no man put asondaaa...). Fuji, Apala and Sakara music are more difficult for Ghanaians to absorb. They are more traditionally based with Islamic roots. But if you live in a place where you hear a certain music type being played over and over again, and see the people cooing over it, you cannot help but get infected yourself. That is why many of us will never forget names like the late Alhaji Sikuru Ayindé Barrister, Kollington Ayinla, or Mama Salawa Abeni. Today, Fuji music has morphed into the Yoruba variant of hip-hop. But for those of us who were there in the early 80s, it is the music of Sunny Adé (is there any musician who has sung his way into the hearts of the Yoruba more than this man who has so many wonderful tracks you won't know which ones to choose as your favourites?) and Ebenezer Obey (who is now into gospel music having also fallen victim to the excessive religiosity that is now afflicting many parts of Africa) that we have continued to enjoy long after we left the country even if we do not understand all the mgbati mgbati.

Then things started getting bad. Many of us saw the signs very early because we had seen similar signs in Ghana. Salary delays had started. Contracts were not being renewed. It was becoming more difficult to get jobs. Prices were going up. Some construction works were being terminated midway. Remittances through the banks were becoming more difficult to get as the black market rates of the naira started running away from the official rates.

They did not sack us from their country. We had survived “Ghana Must Go” 1 and 2. We left on our own when they relieved us of our teaching jobs. It was difficult to get new jobs. We packed our things and went away, leaving behind so many grieving students and, in town, a few lovers with broken hearts. Our hearts, too, were broken. But we had to move on. Those who were too old to brave the journey to another part of the world returned to Ghana and went back to the teaching service or whatever else they were doing before the Agege craze. Many of the young ones came back to Ghana only to re-saddle and set forth again. Some of the “constro” boys, ever the most daring, took the desert road to Gaddafi's Libya. Some of them lost their lives on the way. Some of us came to Europe. Others went to North America. There were those who made it to other African countries like South Africa, Botswana, Zambia, or any country willing to accept them. Anywhere else was better than the difficult days of Rawlings' military Ghana. No matter where we found ourselves after the Nigerian adventure, it was the money we had put by while working in that country that helped us to start our new lives.

Today, it is said that more than half of Nigeria's 160 million people live on less than two dollars a day. The naira is now 150 to a dollar. The largest note is 1,000 naira (equivalent to 12 ghc). A proposal to print 5,000 naira bills was dropped. Another to re-denominate the naira was also discarded. A bottle of Guinness is around 300 naira and Semovita is 250 (na kekere bi dat o). The molue conductors at Oshodi are no longer shouting: “Enter with your ten ten kobo – 50 kobo one naira no change”. That belongs to a time in the distant past. The trip now costs 100 naira.

Nigerians are finding it difficult to exist on their monthly salaries. Many have voted with their feet and for some, even Ghana is better to live in. To be sure, though the Nigerian economy may not be riding the giddy Olympian heights of the late 70s, it has never descended into the gutters that the Ghanaian economy found itself in the same period. But the best is over and many Nigerians will give an arm to have the economic conditions of the seventies and early eighties back - those very conditions that made their country so irresistible to so many Ghanaians.

Yes, there are Nigerians who are crooks, cheats, bandits, religious fanatics and what have you and the country does seem to have a bit more than its fair share of such elements. But the fact still remains that MOST ordinary Nigerians are honest, peace loving, God-fearing, very resourceful and friendly people. You have to live in the country to see these ones whom we do not hear much about. You can also ask the thousands of Ghanaians still living there. And, oh, the country itself is, actually, really beautiful.

For many of us, since Nigeria was our first foray outside our native land, the country remains special to us. We still have fond memories of all those wonderful years we spent there. How can we forget? I have not been back there since I left 26 years ago. I very much want to visit and walk the old paths again. What a wistful experience that will be!

Kofi Amenyo ([email protected])

2024 elections: We’re adopting new strategies; there’ll be no big rallies — NPP’...

2024 elections: We’re adopting new strategies; there’ll be no big rallies — NPP’...

"I can now see clearly with my two eyes, thanks to the generosity of Afenyo-Mark...

"I can now see clearly with my two eyes, thanks to the generosity of Afenyo-Mark...

Election 2024: Power outages will affect NPP – Political scientist

Election 2024: Power outages will affect NPP – Political scientist

NPP is 'a laughing stock' for luring 'poster-stickers', 'noisemaking babies' wit...

NPP is 'a laughing stock' for luring 'poster-stickers', 'noisemaking babies' wit...

Dumsor: Matthew Opoku Prempeh must be removed over power crisis – IES

Dumsor: Matthew Opoku Prempeh must be removed over power crisis – IES

PAC orders WA East DCE to process requests from their MP

PAC orders WA East DCE to process requests from their MP

Defectors who ditched Alan’s Movement to rejoin NPP were financially induced – A...

Defectors who ditched Alan’s Movement to rejoin NPP were financially induced – A...

Dumsor: Akufo-Addo has taken Ghanaians for granted, let’s organise a vigil – Yvo...

Dumsor: Akufo-Addo has taken Ghanaians for granted, let’s organise a vigil – Yvo...