It is not easy to write an autobiography. You must first convince yourself that your life is a story worth telling. Then you must also be able to tell it well. Oheneba Akyeampong, retired Senior Lecturer at the University of Cape Coast and Fulbright Scholar, does his utmost on both counts and largely succeeds.

What was his life? He was born in Kumasi. Coming from a poor family, he struggles financially through elementary school, Teacher’s Training College, University of Ghana, joins the Agege train, goes to Sweden where he bags a PhD, comes back to Ghana, teaches for several years at the University of Cape Coast and goes on a one year Fulbright Scholarship. He was also a member of the National Accreditation Board. He spends his last working years teaching at a private university from where he retires to write his life’s story. In the telling, he touches on several issues that affect us not only as Ghanaians but also as human beings.

Akyeampong tells of his early days in Ghana in the 1950s, working in Accra in the 60s and attending Teachers Training College. As a teacher, he studies on his own and gets good grades at the GCE “O” and “A” Levels that enable him to enter the University of Ghana where he becomes a member of the “Joromi fraternity” of former teachers on study leave. He teaches at Winneba Secondary School after that. It is a story many Ghanaians in his age group will recognise.

It is when he describes the time he leaves Ghana for Europe that the story really picks up. His first stop outside Africa is in Sweden where he obtains a doctorate degree in Human Geography whiles working full time and raising a family. The Fulbright year in the USA enables him to compare these countries with Ghana.

He points out the stark differences in the political processes in Sweden and USA on one hand and those in Ghana. He notes that there is no voters’ registration process in Sweden yet no one complains of being unable to vote because he is left out of the voters' registry. In Sweden and the US, election results are not declared by an almighty Electoral Commissioner from figures she alone is privy to. The press calls the accurate results at all times.

Akyeampong compares what he calls the “spuriously religious” nature of Ghanaians and Nigerians with the secular nature of the advanced countries he has lived in. Citizens of the largely secular Sweden, Norway, U.K and USA are far more law abiding than the excessively religious Africans. These secular countries have also built more prosperous countries than the very religious ones. Himself an ardent church goer, Akyeampong’s point could not have been made any clearer.

Akyeampong spent most of his working life in Ghana in the education sector and some of the best parts of the book are his thoughts on the subject. Why do the top 50 secondary schools in Ghana consistently perform better at external exams than the rest? His answer is that the top schools have a “long-established culture of devotion to duty”. He thinks day students perform better at the lower levels of the educational ladder than boarding students.

His most pertinent observations in the educational sector relate to university education in Ghana. His work as a panel member of the National Accreditation Board and his own University’s Academic Board gives him an insider’s knowledge on the subject. He complains of poor theses that are passed and honours students who do not merit the high classes they are given. Is there really grades inflation at our universities compared to his time?

These days, university departments are instructed to award first class degrees to a certain percentage of graduating students irrespective of the absolute level of performance. In his time, there was no First Class in a graduating class if no one was judged to have deserved it! But, surely, one cannot argue that brilliant students existed only in the past. They still do today even with the proliferation of First Class graduates. The brilliant students of today shine wherever they go in the world. Perhaps Ghana is following the trend in Europe and North America where the system passes everybody but allows the very gifted to go on and shine on their own even if they come from Africa.

From his story, examination malpractices have been common in Ghana since long. He sees it at his village elementary school at Kwamankesse in the early 70s. But they may have been rare occurrences at the time. Now, they happen all too often especially at high school level. They occur in our universities too where the problem is not so much leaked examination papers but lecturers who, for various reasons, award grades to students who do not merit them.

He has a lot to say about corruption in Ghana. This is our old problem and he does not really bring any new insights to it. But who can say anything new about this bugbear in our socio-economic life?

Akyeampong dabbles in Ghanaian politics. He fails in his bid to enter parliament on an NPP ticket – perhaps the one thing that his oft-mentioned dedication and commitment to duty did not enable him to succeed at. He does not try again. He tells us he never joined the Ghana Young Pioneers in his youth because, even as a teenager, he abhorred Nkrumah’s policies.

Those of us who also lived at the time remember that, as teenagers, we did not decide such things on our own. We took after what our parents and influential elders in society told us. Akyeampong, probably, did not join the Pioneers because the significant others in his vicinity were anti-CPP. The Young Pioneer movement was made attractive to the youth with free uniform, free boots, free everything. He said the Chinese style uniforms were drab. If you came from a poor family which could not afford such things, these uniforms were anything but drab.

There is a somewhat related issue I want to devote some time to. Akyeampong says that the language policies of both the colonial government and Nkrumah’s government sought to stifle local languages. This is difficult to substantiate especially in the case of Nkrumah. He encouraged the use of local languages and his government continued with the work of the Bureau of Ghana Languages set up in the colonial era. Six local languages were used regularly on national radio. There was a lot of vernacular literature including the popular bi-weekly newspaper, Nkwantabisa, which also had versions in other languages.

Adult education taught our elders to read and write local languages. Nkrumah needed to reach the illiterate folk. His support base was the so-called “veranda boys” who hardly spoke English. Vernacular was used more then than it is now! Those who left elementary school at the time could read and write one local language fairly well. That cannot be said of today’s basic school leavers.

The “Do not speak vernacular” policy he complains of was a local requirement by elementary schools meant to encourage the pupils to be better at English, necessary for the study of other subjects. It was not meant to stifle local languages and was not, anyway, a Ghana Education Service policy.

Even before colonial administrators took over the country, church missionaries were working in the major vernaculars as a means of preaching the gospel. After independence, it was our duty to develop those languages and Nkrumah realised that too. Today, the overwhelming dominance of a Twi variant of the Akan language in Ghana is suppressing other local languages. This is not due to any colonial policy.

He discusses the pull factors that attracted a lot of Ghanaians, including himself, to Nigeria in the late 70s and early 80s. But he does not give similar weight to the push factors which were equally strong. The Nigerian oil boom coincided with the most difficult times in the history of our economy when even toilet roll was difficult to get.

There are a few inaccuracies in the narrative. The Gas called three pence tro, not “tro-tro”. The repeated form comes from the conductor shouting out the fares: tro tro, tro tro which became the generic name of the vehicle. Dag Hammarskjöld died in Zambia, not in the Congo. The incorrect spellings of well-known proper names cannot be excused. The Hall name in Legon is Akuafo, not Akuaffo. The former president’s name is Kufuor, not Kuffour and the current president’s name is Akufo-Addo, not Akuffo-Addo. These things matter!

These minor faults, and a few others due to poor editing, do not detract from the full enjoyment of the book and the lessons it teaches Ghanaians about our history and the current state of our affairs. Throughout his narrative, he is at pains to examine the extent to which we, as individuals, are in control of the things that happen to us in life and how others can affect that trajectory. It is a very human story.

There are many interesting, and often hilarious, anecdotes especially about his travails in the white man’s land – something that may be of interest to the many Ghanaians who are aspiring to reach there. How do you survive once you find yourself there? His vivid evocation of life in the “good old days” makes a delightful read.

Perhaps the greatest strength of Akyeampong’s life story is that he has dared write about it defying the sorry state of publishing in our country. We complain that our leaders do not write their stories and we are left the poorer for it. Akyeampong has done his part and, in an easily accessible language, given us a very rich account to contemplate about. How many of us will buck the still prevalent trend that Ghanaians do not read and take up this book?

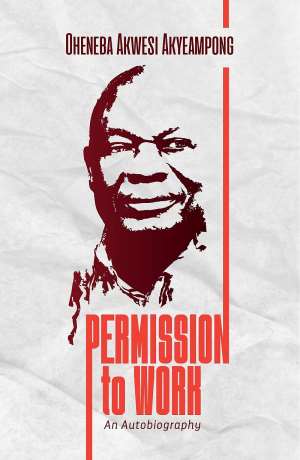

Permission to Work: an Autobiography. By Oheneba Akwesi Akyeampong. Type Company Ltd, Tesano, 2021; 340 pages. Price: 100 ghs.

Kofi Amenyo ([email protected])

Meta releases new version of conversational AI across its platforms

Meta releases new version of conversational AI across its platforms

Cape Town named Africa’s Best Airport 2024 by Skytrax

Cape Town named Africa’s Best Airport 2024 by Skytrax

Bono East: Four injured after hearse transporting corpse crashes into a truck

Bono East: Four injured after hearse transporting corpse crashes into a truck

‘Be courageous, find your voice to defend our democracy’ — Sam Jonah urges journ...

‘Be courageous, find your voice to defend our democracy’ — Sam Jonah urges journ...

Exodus of doctors, nurses and teachers have worsened because of unserious Akufo-...

Exodus of doctors, nurses and teachers have worsened because of unserious Akufo-...

2024 election: Avoid insults, cutting down people in search of power – National ...

2024 election: Avoid insults, cutting down people in search of power – National ...

‘You passed through the back door but congratulations’ — Atubiga on Prof Jane Na...

‘You passed through the back door but congratulations’ — Atubiga on Prof Jane Na...

Government’s $21.1 billion added to the stock of public debt has been spent judi...

Government’s $21.1 billion added to the stock of public debt has been spent judi...

Akufo-Addo will soon relocate Mahama’s Ridge Hospital to Kumasi for recommission...

Akufo-Addo will soon relocate Mahama’s Ridge Hospital to Kumasi for recommission...

We must not compromise on our defence of national interest; this is the time to ...

We must not compromise on our defence of national interest; this is the time to ...