‘’African art, like any great art, some would say, in any case more than any other, and for a long time if not always, is first of all in man, in the emotion of man transmitted to objects by man and his society.

This is the reason why one cannot separate the problem of the fate of African art from the fate of the African man, that is to say the fate of Africa itself.”

Aimé Césaire, Discours sur l’art africain,1966.)

Readers know by now that no one can continue to follow restitution matters for long unless she or he is an optimist by nature. The last few months have given us more reasons than ever to believe that the future will bring us more joyful news. It is therefore useful to review very briefly some of these events and point out some of the difficulties on way. To be optimistic does not necessarily imply ignoring real difficulties that anyone must face who wants the restitution of thousands of looted African artefacts from western museums.

The greatest event in the history of restitution of looted African artefacts was undoubtedly the famous declaration made by the French President Emmanuel Macron on 28 November 2017 when he declared before an audience of students at the University of Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso, that ‘African heritage can’t just be in European private collections and museums. African heritage must be highlighted in Paris, but also in Dakar, in Lagos, in Cotonou.’ He declared his intention that within 5 years he wanted to see conditions established for the temporary or permanent restitution of African heritage to Afrtica. That was the first time, in the history of African and European relations that a European statesman, and for that matter a French president, had admitted that it was wrong to keep looted objects of Africans in Europe whilst Africans had no possibility to see and admire their own patrimony which is on show everyday in Paris and London. This was a miracle.

Macron’s Ouagadougou Declaration was received with great joy and surprise by many of us. We could not believe that any Western statesman would one day admit that it was wrong to keep the looted artefacts of others and that these objects must be returned. Many British museum directors were shocked and deliberately or otherwise, misunderstood Macron’s intentions and declared he wanted to empty their museums. The German museum directors were equally shocked. When a group of German, international scholars and NGOS petitioned the German Chancellor to take a position on the issue, she did not reply and up to now has still not given an answer. The German Minister for Culture and the German Museums Association quickly produced Guidelines for dealing with objects acquired in colonial contexts. Although many said that Macron did not speak for Germany, they were all in no doubt that the declaration of the French president would put pressure on them.

Many of us were somewhat sceptical about the seriousness of the propositions of the young French president against whom we saw a whole mass of French Museum directors, including the President of the Musée du Quai Branly-Jacques Chirac and the French art dealers, at rue de Seine, Paris, up in arms. The French president then appointed in March 2018 two renowned scholars, Bénédicte Savoy, France, and Felwine Sarr, Senegal, to study the issue and report to him in November 2018 with concrete proposal for action

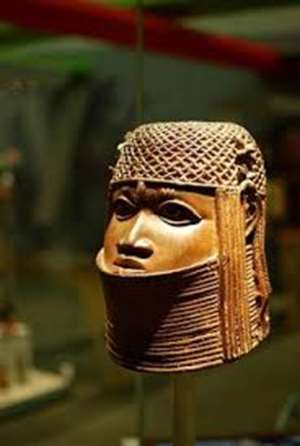

One of the looted Nok pieces held by the Musée du Quai Branly Jacques-Chirac with a post factum consent of the Nigerian authorities even though the ICOM Red Book for Africa forbids their export outside Nigeria.

To the surprise of many, Stephan Martin, president of the museum that has most of the looted African artefacts in France, some 70,000 out of a total of 90,000 turned out to be supportive of restitution and gave the best and strong argument for restitution: Africa was the only continent that had most of its artefacts outside the continent; some of the objects must be returned to the continent. That was a miracle

Stephan Martin and his museum staff were very helpful in the preparation of the Sarr-Savoy report The two scholars submitted their report on 23 November 2018 to the president who promptly accepted their propositions and instructed that 26 looted artefacts should be returned to the Republic of Benin.

The report shocked many more persons for its general recommendation that African artefacts should be restituted that have been taken without the consent of the African owners, including objects brought by the so-called scientific expeditions, such as the Dakar Djibouti Mission described by Michel Leiris in Afrique fantôme.

Fang mask, Gabon, now in Musée du Quai Branly, Paris.

Martin who had taken part in consultations with Bénédicte Savoy and Felwine Sarr suddenly turned out to be one of the fiercest critics of the report: he declared that the report was not a collective work but that of two persons; that the report was a document on the perception of African youth and intelligentsia, born out of the frustration of colonialism and its consequences; he added that the report was a bad answer to the courageous question posed by the President of the Republic This was a reverse.

Nigeria which had hitherto pursued a policy of quiet diplomacy and non-confrontation, declared that it wanted all its looted artefacts back without conditions: The National Commission for Museums and Monuments had called for the unconditional return of cultural artefacts and works taken illegally from Nigeria and other parts of Africa.

But soon thereafter, we began hearing news that Nigeria was preparing to borrow its own looted Benin artefacts under a scheme worked out with members of the so-called Benin Dialogue Group-British Museum, London, Horniman Museum, London

Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, University of Cambridge,

Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford, Humboldt Forum, Berlin,

Museum für Völkerkunde, now Museum at Rothenbaum, Hamburg’

Staatliche Ethnographische Sammlungen Sachsen, Leipzig and Dresden,

Weltmuseum, Vienna, Museum Volkenkunde, Leiden,

Världskulturmuseerna, Stockholm.

Baule mask. Côte d’Ivoire, now in Musée du Quai Branly.

A communique from the Benin-Dialogue Group announced that Nigeria will borrow Benin artefacts on temporary basis for a permanent display of the Benin artefacts in Benin City from for where the artefacts were looted in 1897, in the reign of Oba Ovonramwen. We received this message with incredulity. This was a reverse. We have condemned this arrangement that turns looters into owners and owners into borrowers. Nigeria has many brilliant lawyers who probably will be able to explain to the man on the street how owners can borrow their own looted property from the same persons that stole them. Some Nigerian papers and members of the administration, deliberately or otherwise, blur in their reports and statements the difference between restitution and return on temporary loan. Nor do they mention that the borrowing is on condition that a new museum in Benin City be completed.

What worries me also is the introduction of the idea of borrowing a cultural artefact into our continent. This is a European or western idea of the worst sort. In our African societies, there have not been such borrowings.

Face pendant, Baule, Côte d’Ivoire, now in Musée du Quai Branly, Paris, France.

Each society produced the artefacts it needed for its own purposes. One society may have looked at ideas and practices elsewhere and copied or modified well- known forms but there was no borrowing of the physical objects themselves. It would not make sense. That explains partly the extraordinary variety of artefacts on our continent. We produce what we need for our own use and have no intention of borrowing or stealing from other peoples. Now, the so-called Benin Dialogue Group which is mainly a European dominated group, is getting us used to the idea of borrowing our own artefacts they have stolen. We shall soon be borrowing from all over the place instead of producing our own artefacts. Why do the Europeans not produce their own artefacts and return Benin artefacts to the people of Benin, the Edo? Why do they not produce replicas of the artefacts? They are making borrowing or stealing respectable.

What message is this borrowing arrangement sending to people in Nigeria, in particular the youth? Do we want them to believe that stealing cultural artefacts is normal and that you may even be able later to lend them to the owners themselves? In a country where others have stolen or borrowed billions of naira from State sources, do we want to make normal such borrowings? The State could soon be borrowing from persons who should in normal circumstances fear the possibility of facing trial and imprisonment.

Chokwe, Democratic Republic of Congo, Africa Museum, Tervuren, Belgium.

Now, some of the questions which revealed the curious nature of the arrangement between the Nigerian side and the Europeans are no longer mentioned. We hear no more about security of the objects, costs of transport and insurance and, above all, the immunity from legal action that the present illegal holders of the artefacts sought. They feared, and rightly so, that some Nigerians may seek a judicial order to restrain them from sending the objects out of Nigeria until questions of legal ownership have been clarified.

This year also saw an exhibition of looted Ethiopian artefacts seized by the British Army in 1868 from the Ethiopian Emperor Tewodros II who committed suicide rather that surrender to the invading British Army. In the context of this exhibition, Magdala 1868, the director of the Victoria and Albert Museum, Tristram Hunt, felt he could make a generous offer to the Ethiopians by offering a loan of some of the Magdala artefacts. The proud and self-respecting Ethiopians refused the absurd proposition to borrow their own looted artefacts.

We must put on record our great appreciation of the efforts by President Patrice Talon of Republic of Benin to ensure the commencement of the restitution process from France to Africa. We also express our gratitude to the following for their excellent statements at the UNESCO Conference on 1 June 2018: Aurelien Agbenonci, Minister of Foreign Affairs, Benin, Abdou Latif Coulibaly, Minister for Culture, Senegal, Hamady Bocoum, Director -General, Museum of Black Civilizations, Dakar, Senegal, Alain Claude Bilie By Nze, Minister for Sports, Culture, responsible for tourism, Gabon, and George Abungu, Director-General Emeritus, National Museums, Kenya (UNESCO’s Major international conference on circulation of cultural property and shared heritage: what new perspectives?) All the African speakers made it abundantly clear that the looted artefacts must be returned. After this conference, no European museum director can honestly allege that he had never heard Africans demanding restitution of their looted artefacts.

Gelede mask, Yoruba, Nigeria, now in Musée du Quai Branly, Paris.

It is our fervent hope that other African leaders would put in similar efforts and leave no doubt in the minds of the illegal holders of looted African artefacts that we are determined to recover our cultural heritage that has been taken to other continents whilst we in Africa lack these precious creations in the places of their birth.

The Belgian royal family declined to attend the re-opening of the Africa Museum at Tervuren on 8 December 2018 because of the continuing debate about restitution of artefacts that the Belgians, like all colonialists stole from their colony, Congo. When a king refuses to attend the formal re-opening of a museum built by his ancestor because of restitution debate, then one must recognize how important the issue has become. Or was it a clever move by the monarchy to avoid any associations with the cruel king Leopold II who ordered the hands of children to be cut off when their village did not produce enough rubber in the Congo?

In the last month of this year, we saw the opening of the museum of Black Civilisations in Dakar, Senegal, that encouraged us and a few weeks ago, a workshop on restitution at University of Ghana, Legon, supported the main views of the Sarr-Savoy report (See Annex I). The International Council of African Museums (AFRICOM) has also issued a press release in support of the Sarr-Savoy report. (Annex II) Hopefully, African States will support AFRICOM so that it can effectively coordinate the efforts of the various museums on our Continent in the matter of restitution

Figure of a seated male; one of the three looted Nigerian Nok terracotta bought by the French, even though they knew they were looted, now in the possession of the Musée du Quai Branly, Paris, France, with a dubious post factum consent of the Nigerian government.

In the last few days of the year, we received a statement by two German State ministers, Monika Grütters and Michelle Münterfering, both in the area of culture, endorsing the main conclusions of the Sarr-Savoy report. The ministers asked how it was possible that German museums could hold objects in their collections acquired in a manner that contradict German values of today (Eine Lücke in unserem Gedächtnis) This was the last miracle of the year. Readers should note that this is quite a change from many western arguments that insisted that we evaluate previous criminal activities such as slavery and colonialisms, in terms of the values of the time when the acts were committed and not the values of our times.

The two German ministers expect museums to show themselves ready and open to face questions of restitution. Provenance research should not give the impression that research is only being used as delaying tactic. Human remains do not belong to European depots but must be handed over to relatives of the deceased. Germany must increase its efforts for digitization of what the museums hold and museums must fully inform visitors to exhibitions how objects came to German collections. The discussion on the German colonial past must be extended to school books and television programmes. Germany must intensify its international cooperation with the African States in a spirit of partnership and respect. The ministers also approved the international dialogue with African States such as the conference President Macron has announced for next year.

Kpan pre mask, Goli, Baule, Côte d’Ivoire, now in Musée du Quai Branly, Paris.

The German government will strengthen knowledge and awareness about the German and European colonial past. German and European colonial pasts constitute enormous historical, moral and political challenges for Germans: ‘European colonialism has deprived concerned societies of part their identities that is not replaceable This re-examination of the colonial past in part of the responsibility of Germany and Europe for their colonial history and a pre-condition for reconciliation and understanding and for a better common future.’

These are words that some us have being waiting for decades to hear from the former colonial masters. Only the coming year will tell whether these were serious words or merely intended to pacify the African public. For those concerned with restitution, the mere hearing of such tones has a soothing effect, as opposed to the supercilious and arrogant words of many European leaders and museum directors, convinced they have been appointed by God to oppress and rule the rest of mankind. But we shall judge Austria, Britain, France Germany, and the Netherlands not by their pronouncements, but by their deeds. We shall specifically watch out what happens to the looted Benin and other artefacts in the Humboldt Forum that is due to open in November 2019. Five hundred years of relations with Europeans have taught us some lessons.

‘This time, I carry out the operation alone and penetrate into the sacred small place, carrying Lutten’s hunting knife in order to cut the ropes to the mask. When I realise that two men - in no way at all menacing, have entered behind me, I realise with an astonishment which after a very short time turns into disgust, that one feels all the same very sure of one’s self when one is a white man and has a knife in his hand...” Michel Leiris, Afrique fantôme.

Kwame Opoku.

Akan gold weight, Ghana, now in Musée du Quai Branly, Paris, France.

ANNEX I

MIASA-Merian Institute for Advanced Studies in Africa

University of Ghana, Legon, Ghana

International workshop on:

ISSUES OF RESTITUTION AND REPATRIATION OF LOOTED AND ILLEGALLY ACQUIRED AFRICAN OBJECTS IN EUROPEAN MUSEUMS

13-14 December 2018

Workshop Convenor: Dr Wazi Apoh

Statement by workshop participants

Drawing on earlier exchanges on the African continent, scholars, museum practitioners, heritage custodians and policy-makers, gathering at MIASA at the University of Ghana, discussed a number of shortcomings and inadequacies in the current debate on restitution and provenance issues.

We acknowledged and engaged with previous and current African initiatives and perspectives. The international debate needs to quickly gain a much-needed African dimension. Most discussions now centering on Paris, Berlin or Brussels lack clear African inputs and perspectives from scholars and practitioners, often failing to reflect the concerns of African researchers on stakeholder participation, as well as the challenges/needs and potentials of African museums. Additionally, only a few African governments and relevant organisations have taken positions, or at least started discussions about their attitude towards the debate.

The lack of trust of African restitution advocates towards European museums and governments is unlikely to reduce until there is: a) a quick return of those highly valued objects, as requested by African governments and communities, where illegal acquisition is undisputed with a clearly established provenance history; b) more joint (African-European) efforts to establish the provenance of other key objects. Transparency and accessibility are also key to establishing trust. Providing inventories of objects and the opening of museum storage rooms to African experts must become established principles. In addition, there should be access to archives in European museums or other state institutions.

While it is necessary to prioritize the objects to be returned, a long process of re-evaluating or establishing the provenance of objects is unacceptable and cannot be an excuse for slowing down the process of restitution. Undisputed, illegally acquired objects must be subject to unconditional restitution from and by state museums in Europe.

The governance of restitution processes, with clarity of principles and procedures, is equally required. The African Union and Regional Economic Communities are invited to develop a position and to start negotiations about such principles. The instances of some successful – albeit slow and painful - precedents in restitution to Africa could be turned into positive examples or provide

elements for deducting more general guidelines. These guidelines could include: a) early negotiation of terms of reference between the relevant partners (museums, governmental bodies, communities); b) clarification of any competing claims on the objects themselves, but also of legitimacy and representativeness; c) approximate timelines for additional research on the objects’ provenance (if deemed necessary); d) validation of the authenticity of restituted objects; e) joint development of an exhibition policy including within the community AND country of origin (at times countries of origin when pre-colonial entities are ‘transborder communities’) AND at European museums that transfer objects to Africa.

There is also an observable lack of homogeneity on the European side. The Macron initiative (following requests from Africa) is laudable and has provided openings and in turn influenced debates in Germany and Belgium. Yet this is not the case for most other member countries of the European Union, North America and elsewhere. The EU itself has not yet taken a visible position. It is also expected that individuals and private institutions with looted and illegally acquired objects of African origin will begin to show willingness to return these objects.

Interdisciplinary and transregional research as well as transregional and transnational museum cooperation are promising avenues for overcoming the decades-old deadlock in the restitution of illegally acquired/looted objects from Africa. We also expect that while this process is unfolding, it is the joint responsibility of European and African authorities to take urgent steps to scale-up African museum institutions to ensure that, once returned, these looted objects are properly housed in secure institutions that meet the best possible standards of museological practice.

We are aware that various initiatives are underway on the African continent that champion the cause of restitution, and we give our full support to such African-led initiatives.

Signatories:

Wazi Apoh (University of Ghana)

Kokou Azamede (Université de Lomé)

Kofi Baku (University of Ghana)

Gordon Crawford (Coventry University; MIASA)

Andreas Eckert (Humboldt University)

Patrick Effiboley (Université d’Abomey-Calavi)

Gertrude Aba Eyifa-Dzidzienyo (University of Ghana)

Albert Gouaffo (Université de Dschang)

Zacharys Gundu (Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria)

Dag Henrichsen (Centre for African Studies, University of Basel)

Steven H. Isaack (Heritage Watch, Namibia)

Kwame Labi (University of Ghana)

Thomas Laely (Ethnographic Museum, University of Zurich)

Andreas Mehler (Arnold Bergstraesser Institute, University of Freiburg)

Abena D. Oduro (University of Ghana; MIASA)

Alexis von Poser (Lower Saxony State Museum, Hanover)

ANNEX II

PRESS RELEASE

Harare, Zimbabwe

Rabat, Morocco

For Immediate Release

December 24, 2018

THE INTERNATIONAL COUNCIL OF AFRICAN MUSEUMS (AFRICOM HAILS THE SARR-SAVOY REPORT URGING RESTITUTION OF AFRICAN HERITAGE REMOBILIZES ITS NETWORK TO RECEIVE COLLECTIONS RETURNED TO AFRICA

AFRICOM welcomes the recommendations of the Felwine Sarr & Bénédicte Savoy report (Restitution of African Heritage, 2018) endorsing the restitution of African objects from French museums and reiterates the willingness and readiness of African museums, universities, cultural institutions and heritage communities to reintegrate African tangible heritage (museum collections, natural and cultural tangible heritage, archives) back in institutions and with communities in African countries of origin.

AFRICOM salutes and enthusiastically supports the recently reiterated demands for the restitution of museum collections by African countries and pledges to continue organizing restitution efforts through its pan-African museum professionals’ network.

AFRICOM has been reorganized to support restitution of African heritage and has mobilized its network: by collecting and compiling African countries' lists of objects in museums from its delegates, and by organizing future capacity-building workshops involving French and African museum professionals in line with two of its constitutional objectives, namely, “to fight against the illicit traffic of African Heritage and to strengthen the collaboration and co-operation among Museums and Museum professionals in Africa, as well as develop exchanges with Museum professionals abroad.”

AFRICOM is also encouraged by French President Emmanuel MACRON’s response to the Report in calling for a Euro-African conference on the issue as well as for kick-starting the restitutions by returning 26 heritage objects to Benin. This is a good start. African museums and the heritage community recognize the leadership of Benin’s President Patrice TALON for getting the process in gear with the caveat that restitutions to all African countries must be ongoing and instituted with former colonial powers in order to effect decolonization and establish new relationships going forward.

It is fitting that this process begins between France and all independent African States, members of the African Union (AU) (including North African countries), and heritage bearing stakeholder communities throughout the continent. The African museums' community unanimously welcomes this long-awaited event and AFRICOM stands ready to cooperate with Europeans to continue building capacity in African museums to ensure that all returned objects are well conserved, curated and documented so that they are accessible to all.

May the return of the African heritage on African soil permit the world body to learn and benefit from the shared values this heritage conveys as witness to the history of humanity and its source, its present and its future in Africa.

CONTACTS: International Council of African Museums (AFRICOM) Reorganizing Committee Rudo SITHOLE (Executive Director, AFRICOM) Tel: +263 77 443 7195/Email: [email protected] Ech-cherki DAMALI (Vice-President, AFRICOM) Tel: +212 661 42 21 21/Email: [email protected]

Avoid pre-registered SIMs, buyer and seller liable for prosecution – Ursula Owus...

Avoid pre-registered SIMs, buyer and seller liable for prosecution – Ursula Owus...

Election 2024: Mahama has nothing new to offer Ghanaians, Bawumia is the future ...

Election 2024: Mahama has nothing new to offer Ghanaians, Bawumia is the future ...

OSP files fresh charges against ex- PPA Boss

OSP files fresh charges against ex- PPA Boss

Withdraw unreasonable GH¢5.8m fine against former board members – ECG tells PURC

Withdraw unreasonable GH¢5.8m fine against former board members – ECG tells PURC

Akroma mine attack: Over 20 armed robbers injure workers, steal gold at Esaase

Akroma mine attack: Over 20 armed robbers injure workers, steal gold at Esaase

Those who understand me have embraced hope for the future — Cheddar

Those who understand me have embraced hope for the future — Cheddar

Ghana will make maiden voyage into space should Bawumia become President — Chair...

Ghana will make maiden voyage into space should Bawumia become President — Chair...

Train crash: Despite the sabotage, we shall not be deterred and will persevere —...

Train crash: Despite the sabotage, we shall not be deterred and will persevere —...

Tema-Mpakadan railway project a perversion of the original viable concept design...

Tema-Mpakadan railway project a perversion of the original viable concept design...

Train crash: Elsewhere, everyone involved in the test will either be fired or re...

Train crash: Elsewhere, everyone involved in the test will either be fired or re...