Ground-breaking treatments against the Ebola virus are taking the fight against the haemorrhagic disease to the next level with the start of clinical trials in the eastern Democratic Republic of Congo. Four experimental drugs will be administered to patients in the first such study during a deadly epidemic, raising hopes that scientific research will soon be able to offer both a vaccine and treatment for Ebola.

“What's exciting is the fact that there's finally something to offer patients whose life is in danger,” says David Heymann, an expert in infectious diseases at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medical. “As far as I'm aware, this is the first time that this has been tried for such a complex trial during an outbreak situation.”

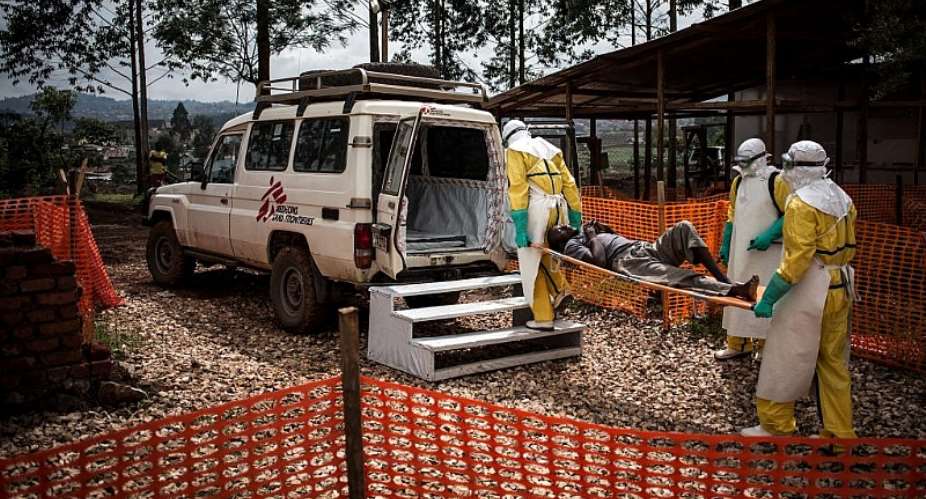

The Congolese government declared an Ebola outbreak in North Kivu province on August 1 and 289 people have died from 500 cases of the disease since then, according to the latest figures published by the authorities.

This outbreak is only the second to use a new unlicensed vaccine from the onset of an Ebola epidemic and it is hoped that the testing of so-called investigational Ebola treatments will further bolster efforts to fight the disease and save lives.

Four treatments have already been used to try to treat patients during this outbreak. However, the use of these drugs has so far not yielded any clear scientific data on their effectiveness because they have been administered under a compassionate protocol.

Reliable data

“The use of therapeutic treatments under this protocol does not provide for the generalisation of scientific evidence collected on the efficacy and safety of each of these treatments,” the Congolese health ministry said in a statement on November 24.

The drugs selected to be part of the clinical trials are ZMapp, mAb 114, Remdesivir and Regeneron. Patients must consent to their inclusion in the trials and the treatments will be selected at random. Those not taking part in the clinical trials will still be offered treatments under the compassionate use protocol. The drugs will be offered free of charge as with the vaccine.

“Every patient who comes to the treatment centre gets one of the four experimental treatments in addition to all the supportive care,” says World Health Organisation spokesperson Tarik Jasarevic, explaining that treating clinicians have until now been deciding for themselves which drug to administer.

The choice of treatment under this compassionate protocol has resulted in the four drugs being used in “more or less the same percentage” and a choice being made on the basis of the condition of the patient as well as the time needed to deliver the treatment, according to Jasarevic. Some of the treatments require multiple doses over time while others can be given in a single dose.

“So far 174 patients have been treated with these experimental, investigational treatments,” says WHO spokesperson Jasarevic. But it is hard to determine which treatments are working especially given the challenging conditions of the outbreak and difficulties over people coming late to treatment centres.

“We had a number of people who died and who received treatment before dying,” says Jasarevic. “Others have been discharged, but we don't know whether they have been discharged because of the treatment or if they would have been discharged in any case.”

The start of clinical trials by no means offers a silver bullet for defeating Ebola. The quantity of data collected during the trial will be a major factor in determining which, if any, of the drugs helps significantly reduce the mortality rate of Ebola. Fatality rates have reached up to 90 per cent in past outbreaks.

Clinical trials could take years

The start of clinical trials in the DRC will form part of larger efforts to carry out research into treatments over the course of several outbreaks until enough data is collected to provide more conclusive evidence.

“The question is when can they be shown to be 100 per cent effective, when can you choose which ones are most effective and get them into use, and the other ones, which are less effective, maybe would be second-line drugs or not used at all,” says Ebola expert Heymann.

Collecting enough data is key - although nobody wants an epidemic to continue in the name of research. “What we want is that this outbreak finishes quickly, we get some data. Next outbreak, we continue, we get more data. And one day to be able to say, we have those four, this one is the best,” says Jasarevic.

Frequent monitoring will continue throughout the trial and drugs that are not effective will be dropped. The trial will eventually include some 450 patients and an analysis model will be developed to draw conclusions from the data.

The effectiveness of Ebola treatments is not the only factor that will be considered, according to Heymann. “Operationalising” the use of these drugs will take into account how they are administered to patients and questions surrounding storage and delivery, an especially important consideration for outbreaks in countries like the DRC where cold storage can be a major problem.

Trials during an epidemic

Conducting clinical trials during a live outbreak situation is rather unique in itself. Clinical trials often use a placebo to provide a control in order to make comparisons to see whether the treatment is more effective or not.

However, a placebo cannot be used in an outbreak situation where the lack of any treatment could potentially be fatal. “There have been studies during the SARS [Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome] outbreak early on, trials in drugs for HIV. But that's a chronic outbreak, it's not an acute outbreak like this,” says Heymann. Chronic diseases worsen over an extended period of time, while acute diseases change rapidly.

“This is unprecedented - that they are able to operationalise a randomised control study with four investigational drugs against Ebola - it's quite amazing,” says Sumathi Sivapalasingam, director of early clinical development and experimental sciences at Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, who have developed one of the Ebola treatments.

Sivapalasingam, who previously worked at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, says there is a route to obtaining regulatory approval for drugs in the US exclusively through animal testing. Although the best method for a virus like Ebola is through a live outbreak situation.

Regeneron's REGN-EB3 Ebola treatment has been used for some five months during the compassionate use phase and Leah Lipsich, the company's vice president of strategic program direction, says they are “cautiously optimistic that our drug will have a positive effect”.

Animal testing

Animal studies have shown that REGN-EB3 significantly reduces the fatality rate among monkeys, according to the US company. However, these studies are conducted in highly controlled conditions.

“We see about a 90 per cent, it depends on the experiment, 90 per cent survival rate of an infection that is almost universally fatal in these animals,” says Sivapalasingam. Regeneron, a company listed on the Nasdaq stock exchange, has commissioned four separate external studies using some 40 animals.

These tests are very specific in terms of the time of Ebola infection, the amount of virus given to the monkeys and when the treatment is given to the animals. “The efficacy is very promising in non-human primates, but obviously it's unclear how this translates into humans,” says Sivapalasingam.

MappBio, which produces the ZMapp treatment, is also confident that its drug is likely to be effective against Ebola, according to the company's Chief Medical Officer Thomas Moench. ZMapp was studied during the 2014-2016 Ebola outbreak in West Africa that spread across borders and killed more than 11,000 people – the world's worst ever outbreak.

The Partnership for Research on Ebola Virus in Liberia II (PREVAIL II) trials in Liberia, Sierra Leone, Guinea and the US used ZMapp with 72 patients and observed a fatality rate of 30 per cent. The study concluded that the treatment appeared to be beneficial, although the results did not reach the threshold for efficacy.

“The epidemic ended before the planned number of patients were enrolled, limiting the information that could be obtained. However, important support for the effectiveness of ZMapp was observed,” says MappBio's Moench, adding that the results indicate a 91 per cent probability that the treatment is better than standard care.

ZMapp has furthermore shown “strong protection” against Ebola in multiple monkey experiments, according to a statement. The company's work has been supported by both the US and Canadian governments and MappBio focuses specifically on infectious diseases.

Designing clinical trials

Due to the previous studies using ZMapp it has been decided to use the treatment as a point of comparison in the clinical trials. “They will be looking for what's called equivalence or better using ZMapp as the baseline because ZMapp is one that's been studied,” says Heymann. This is what is known as the “control arm” of the clinical trial.

The treatments themselves take different approaches to fighting off the Ebola virus. ZMapp and REGN-EB3 are both a cocktail of three antibodies, mAb114 uses a single antibody and Remdesivir is an antiviral drug.

Questions were raised about the inclusion of REGN-EB3 as a “fourth arm” in the clinical trial. The WHO's Expert Consultation on Ebola Therapeutics weighed the use of a fourth treatment and how this would affect the time taken to gather a sufficient number of patients in the trials. Also given that both ZMapp, REGN-EB3 and mAb114 are antibody treatments, there were discussions as to whether it was necessary to include a fourth treatment to examine the different approaches.

Nevertheless the WHO consultation recommended including Regeneron's treatment after “taking these trade-offs into consideration”.

“Comparing an antiviral to an antibody is entirely different,” says Heymann. “They each have different mechanisms of acting,” he adds, questioning whether a further arm of clinical trials in future may include a combination of antibody and antiviral treatments.

Treatment centres

The clinical trials will be conducted by the DRC's National Institute for Biomedical Research and the US National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID). It will start at a treatment centre in Beni, North Kivu operated by The Alliance For International Medical Action (ALIMA), a non-governmental organisation working across the African continent. NIAID says it expects the study to “expand to other Ebola treatment units in the affected area” and in future to other countries.

Médicins Sans Frontières , a French non-governmental organisation, says it is not yet participating in the trial, “but that will change soon, hopefully”, according to a statement.

“There's a general agreement amongst partners in the trial (and MSF fully agrees) that the current protocol still needs some important improvements,” says MSF, who have opened a treatment centre in Mangina, an area considered the epicentre of the outbreak.

“Some of the main issues to fix for instance are the inclusion of REGN-EB3 in the trial, and an adaptation of the analysis model, as the current model is considered not likely enough to yield useful results,” MSF adds. “Once that is solved, MSF will be very happy to contribute to the trial."

Pushing the envelope

All of the work surrounding the compassionate use of Ebola treatments has been developed using WHO's Monitored Emergency Use of Unregistered and Experimental Interventions (MEURI) developed in the wake of the 2014 West Africa outbreak.

This is now helping to guide the next stage of developing the protocol for the clinical trials. But what has been learnt so far is also being fed back into the further development of MEURI for compassionate use.

If the clinical trials do provide reliable data, the use of the MEURI protocol for Ebola outbreaks may not be necessary in the future. Yet it nevertheless provides a framework for any other future deadly outbreaks of infectious diseases where no proven treatment exists.

“It's very exciting that this can happen during an outbreak,” says Ebola expert Heymann. “Offer to people a treatment, but also a vaccine as well. It's changed the way in which you can approach outbreaks.”

WHO's Jasarevic says the standard of care offered to Ebola patients has been really important in fighting outbreaks. Furthermore, the use of vaccines and now treatments takes it to another level. “From the psychological perspective, we have something to offer, we have something to fight the virus directly,” he says.

Tuesday’s downpour destroys ceiling of Circuit Court '8' in Accra

Tuesday’s downpour destroys ceiling of Circuit Court '8' in Accra

SOEs shouldn't compromise on ethical standards, accountability – Akufo-Addo

SOEs shouldn't compromise on ethical standards, accountability – Akufo-Addo

Father of 2-year-old boy attacked by dog appeals for financial support

Father of 2-year-old boy attacked by dog appeals for financial support

Jubilee House National Security Operative allegedly swindles businessman over sa...

Jubilee House National Security Operative allegedly swindles businessman over sa...

Nobody can order dumsor timetable except Energy Minister – Osafo-Maafo

Nobody can order dumsor timetable except Energy Minister – Osafo-Maafo

Mahama wishes National Chief Imam as he clock 105 years today

Mahama wishes National Chief Imam as he clock 105 years today

J.B.Danquah Adu’s murder trial: Case adjourned to April 29

J.B.Danquah Adu’s murder trial: Case adjourned to April 29

High Court issues arrest warrant for former MASLOC Boss

High Court issues arrest warrant for former MASLOC Boss

Align academic curriculum with industry needs — Stanbic Bank Ghana CEO advocates

Align academic curriculum with industry needs — Stanbic Bank Ghana CEO advocates

Election 2024: We'll declare the results and let Ghanaians know we've won - Manh...

Election 2024: We'll declare the results and let Ghanaians know we've won - Manh...