If events continue at this rate and in this manner, I could become a firm believer in miracles, by the end of the year. First, there was the historical Ouagadougou Declaration by the French President, Emmanuel Macron, that African artefacts should be returned to Africa. (1) Then followed Nigeria’s astonishing roundabout turn statement that Nigerian and African artefacts should be returned unconditionally. (2) And now we have the most extraordinary report that Stéphane Martin, the President of the Musée du Quai Branly-Jacques Chirac, Paris, where most of the looted African arts are kept, is in favour of returning African artefacts to Africa. Stéphane Martin is reported as having said :

“There is a real problem which is specific to Africa. Cultural heritage has disappeared from the continent. In the African art exhibitions we have held since opening in 2006, not a single work was lent by an African museum. We ought to do something to repair that.” (3)

In our comments on the Ouagadougou Declaration, we suggested that the proposal to return African artefacts in French museums was likely to meet with, at least, passive resistance from a museum such as Musée du quai Branly, which inherited most of the African artefacts the French looted in expeditions, like the notorious Dakar-Djibouti Mission described in Phantom Africa by Michel Leiris. (4) The museum holds some 75,000 artefacts from African countries South of the Sahara.

Reliquary figure, Byeri, Fang, Gabon, now in Musée du quai Branly, Paris, France.

Readers may recall the opposition to restitution that was shown by officials of the Musée du Quai Branly as Sally Price recounted in her excellent book, Paris Primitive: Jacques Chirac’s Museum on the Quay Branly. (5) When Price raised the question of human remains and restitution of artefacts, she received the following explanation from Séverine Le Guével, head of the international relations at the museum:

“First, the bodies have never functioned as human remains. Secondly, they were (for the most part) given to the explorers who brought them back, not stolen or taken without permission. Plus, they’re not identified. We don’t know who they belong to. Thus, they’ve become art objects; ethnographic objects. That makes a difference. Therefore, they should be preserved like art objects and cannot be destroyed…. And it’s also important to consider all objects that contain human remains. If we were to honour the claims for everything that contain human remains, it would mean giving away the entire collection of the Musée du Quai Branly anything that contains a bit of bone, anything that contains a skull….”

The same official went on to add:

‘‘We at the Quai Branly, as elsewhere in France, have decided to respect the principle of laicité [separation of church and state, very roughly equivalent to secularism]. Therefore, we do not take into consideration any claim based on religion or ethnicity. That’s important…. We’re a public institution, a secular institution operating in the public domain. If you allow the legitimacy of one religion, you allow them all, and then they all cancel each other out. That would put every place in the world on the same level!... Giving credit to all the claims would be to cancel out all of them…If you really believe that these things have a profound meaning, well the museum isn’t made for that. The museum is not a religious space.” (6)

When Sally Price asked Germain Viatte, director at the museum, how they would deal with claims based on religion or ethnicity, she was informed how pleased non-Europeans were to see their cultural objects displayed in the museum; the director further declared:

‘France is both universalist and secular. We need to recognize that [museum collections] belong to the history of our own country, but also to cultures that may have disappeared, or be on the way out, or hoping for cultural revival. We need to take all this into account, but without giving in to a kind of paternalism, confining other people to their particularities and reserving universalism exclusively for ourselves because we’re worried about being “politically correct”. We cannot give in to claims for restitution like those presented to the English for the Parthenon marbles or the Benin bronzes. But what we can do is set in motion international collaboration designed to find viable compromises between different, often incompatible interests, for example, between restitution and the protection of objects”. (7)

Not discouraged by all these depressing statements, Sally Price approached the President of the Musée du Quai Branly, Stéphane Martin, who declared:

“We are not in the business of buying ourselves a clear conscience vis-a vis the non-Western world or becoming an “apology museum,” relaying messages based on the heritages of [cultural/ethnic] communities the way museums in Canada and the United States do for Indians. In France we have a more a more objective vision of culture. It’s free of all instrumentality (nationalistic, pedagogic, etc), though it’s becoming more and more difficult to defend... In my view, the argument for returning the contents of museums to their countries of origin is a rejection, pure and simple, of the museum’s calling which is to show the “Other” which means, by definition: outside of its original environment... Art objects are also ambassadors for their culture, and in that capacity, they’re an element in the dialogue between peoples.” (8)

In view of the report by Price, it comes as a great surprise, not to say a miraculous change, that the President of the Musée du quai Branly now states he agrees with President Macron that African artefacts should be returned to Africa. What is equally surprising about this change of position, is the fact that it took so long. Several years at the museum may have affected Martin’s view on restitution. Stéphane Martin justifies his new position, among others, by the fact that in the exhibitions on African art organized by the museum most artefacts came from outside the African continent and not even one came from the continent. He cites the current exhibition entitled Les fôrets natales in which most of the objects borrowed from outside did not come from African museums but from holders in the Western world. The majority of the 300 objects displayed in the exhibition however come from the vast collection of the museum. Stéphane Martin sounds convincing in his change of opinion on restitution in a very good radio discussion on France Culture in which can be heard, among others, Bénédicte Savoy, Professor of Art History at the Technical University, Berlin and Marie-Cecile Zinsou, founder of the Fondation Zinsou in Cotonou. Art africain : partage ou restitution? - France Culture

Stéphane Martin nevertheless displays that arrogance which seems to come spontaneously and naturally to many Westerners when they deal with Africans or with African matters. They assume what appears to be like a God-given right and obligation to supervise Africans and their activities, including what obviously is African property and resource:

‘Personally, I see no objection in principle to transfers of property, after a definition of a true scientific and cultural project. Africans are going to oppose this, saying it is neo-colonialism. Nowadays cultural action is done at the international level. In order to reframe Mona Lisa, Louvre established an international commission. If tomorrow, an African museum creates the conditions for displaying a collection, I would be very glad to see part of the collection return there. (9)

Nimba shoulder mask, Guinea, now in Musée du Quai Branly, Palais des Sessions, Paris, France.

Martin is ready to support demands for restitution if they are accompanied by a scientific and cultural programme which he approves. He subjects restitution to approval of the use the demander intends to make of the artefact. But where does he derive this right of oversight of the utilization by others of their own property? Martin senses there is something wrong with his opinion and says Africans would call it neo-colonialism. With all due respect to the distinguished museum president, this is neo-colonialism par excellence. Would he for a second think of making such a statement in connection with a claim of restitution by Germans or Austrians for art works looted by Nazi Germany? Martin does not like the word ‘restitution’: ‘We must not see only the work but more so the project. We must not simply see France and her former colonies but a continent that wants to reconstitute its patrimony and the international community that would be ready to assist the continent. It must be a modern desire and not turned towards the past. This is what worries me in the word ’restitution.’ (10)

Master of the mother and child, Dogon, Mali, now in Musée du quai Branly, Paris, France.

Martin does not want to see a restitution turned towards the past. Supposing African demanders really have a vision turned towards the African past which accommodates well the artefacts the French looted, do they not have a right to restore the objects to their previous roles if that would benefit the particular African community through this restoration? After all, these objects were not made for France and the modern Western world, whatever that may mean, but for a particular African community in response to its felt needs. Who are the French to say what the destination of African objects should be? There is here an attempt to limit the vision of Africans and their societies in a direction that suits the French. He seems to want to direct and control artistic freedom of creation. Imagine, if our African forefathers had to consult French authorities about what artistic objects they should create. Martin wants to dictate in which direction our efforts and resources should be utilized. Note how he puts the African continent in opposition to the international community. Is the African continent not part of the international community? It is this Western manipulation of language that allows transfer of wealth from Africa to the West to be presented as aid from the West to Africa.

Would Stéphane Martin raise objection if the word ‘restitution’ were used in the context of Nazi-looted property? Would he insist on programme or project by the demanders before giving his approval for restitution? But who cares about the sensitivity of Africans? Has Martin the right to tell us how we should organize our societies and how we should envision our future? Can he impose on us his modernity and tell us how to utilize objects that were clearly not made for the modern French society he accepts? How about African modernity? We are not condemned or obliged to follow Western modernity and Western mode of living. We have our own conceptions of life and progress which are not necessarily donated by the West. I would like to say to Martin, using the words of Bénédicte Savoy : ‘We must leave it to those who recover their works of art the care and the time to find solutions which suit them.’ (11)

Macron and Martin appear to be sincere in their support for returning artefacts to Africa within the limitations we have mentioned. We must also remember that both are, without saying so explicitly, relying on the notorious lethargy of African governments and their institutions in reclaiming their cultural objects from Western museums. Macron sets conditions of security and experience of curators that ought to be in place in five years’ time when his term of office would expire. Why does he not set a shorter period of two, three or four years so that the matter could be dealt with before the expiration of his term of office? He knows the speed with which the African governments and institutions work on such matters. He also knows that some of the conditions he set are already present in some countries, such as the Republic of Benin which has adequate and modern museum structures to receive the artefacts they requested last year from France but were roundly told restitution was out of the question because of the rule of inalienability of state property.

The lethargy of African institutions is also demonstrated by the fact that since Macron’s declaration on 28 November 2017 none of the African governments has submitted a request for restitution or for that matter made any statement, supporting or rejecting Macron’s declaration. They probably reason they have five more years to do what should have been done so many decades ago. One could expect committed governments and institutions to react within a month or so by submitting a short preliminary list of demands, to be followed by full and longer lists later. How are the many African representatives at UNESCO, in the French capital, reacting to this change of French policy or are they also following a policy of quiet diplomacy?

Statue of a seated woman, Baule, Côte d’Ivoire, now in Musée des Beaux-Arts, Angoulême, France.

Incidentally, African governments and institutions alone cannot prepare a full and final list of their artefacts in Western museums. They would need the assistance and cooperation of the holding museums since in most cases the looted objects have not been seen by the African owners since they were looted in the 19th and 20th centuries. Many packages of looted objects are still lying unopened in Western museums that do not have enough space to display the thousands and thousands of looted artefacts they hold. Only the holders know what they have and where they are to be found. But must the holders wait until the owners have asked them to return the looted items? United Nations/UNESCO resolutions and ICOM Code of Ethics expect them to take the initiative.

Stéphane Martin, recalling the very profitable venture for France in the establishment of the Louvre-Abu Dhabi, is nursing the possibility of a similar venture in Africa:

“It demonstrated that such a partnership is possible and can change our cultural vision. If together, and possibly with international co-operation with other Western partners, we can build one, two or three safe museums in Africa, I would not even consider transfers of ownership as taboo…

Think of the Museum of African Civilisations in Dakar, which has been built by the Chinese and has been empty for three years. Why not consider working on a partnership there? It might not be easy but it would be worth trying.”

Note the paternalistic tone of first paragraph and how Africans appear as passive recipients of assistance from the international community from which they are excluded. When Martin writes about constructing two or three museums for Africa, he is certainly not thinking of African architects such as David Adjaye or Francis Kéré but the French architect Jean Nouvel. If Martin does not want Africans to consider his proposals as neo-colonialist, he must examine the assumptions underlying his statements and the tone.

We can say straight away, without hesitation, that hardly any African State or States would want to pay the horrendous sum Abu Dhabi paid for the right to use the name of Louvre: US$520 million. The French certainly made huge profits from this venture, including an additional US$ 747 for French management and art loans. (12) Such an arrangement has a fantastic advantage for France: the looted artefacts would have returned to Africa but would still be under French control with Africans paying for the costs. The successors to looters would have been doubly paid.

If the French President and the President of the Musée du quai Branly are in favour of returning African artefacts, who then is against restitution in France? In the interview with Stéphane Martin in the Artnewspaper, a hint is given that the French Ministry of Culture is against restitution but so far, the Culture Minister, Françoise Nyssen, has not expressed any view on Macron’s ideas and plans. It is notable though that just recently in 2016, the French Minister of Culture rejected the demand by the Republic of Benin for restitution of the royal Dahomean statues looted by the French Army, under General Dodds, when Dahomey was conquered in 1892-94 on grounds of inalienability of state property. (13)

We would like to assume that the President can overrule his ministers. But can we be sure that this is not a clever division of roles between the President, the president of the museum and the Ministry of Culture? Only time will tell.

Meanwhile, if Emmanuel Macron wants to put beyond all reasonable doubt the hope and enthusiasm he has raised by his Ouagadougou Declaration, we suggest he instructs his officials to return to Africa within a few months, some of the looted artefacts, e.g., Dahomean royal artefacts from the Republic of Benin, as a token of his serious intentions. He should not wait till the end of his term to tell us that certain conditions have not been fulfilled. Since Macron has declared the restitution of African artefacts as a matter of priority, we expect to see soon signs of this priority. The relevant plan of action should be made public and not wait until the last year of his term.

The quest for restitution of African artefacts should be extended to all major French towns that have museums, such as Bordeaux, Grenoble, Lyon, Rouen, Marseille, Nantes and other towns. (14)

With strong allies such as President Macron of France, and the President of the Musée du Quai Branly-Jacques Chirac, Stéphane Martin, the African States, with sufficient concentration on this matter, should be able, at least, to recover some of their artefacts looted in previous centuries. They should be able to secure an agreement in principle for the return of the artefacts when they feel ready to collect them.

Holders of looted African artefacts, Austria, Belgium, Britain, Canada, Denmark, France, Germany, Holland, Italy, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, United States as well as others, are called upon to respond finally to the demands for restitution of African artefacts. They can no longer advance the weak, old, self-serving arguments that have now become obsolescent since the Ouagadougou Declaration. They should abandon the old universalist and racist arguments that were utilized to justify looting and holding of artefacts of African peoples and their oppression under colonial rule. They should abjure theories that contradict and undermine all that has been achieved under the United Nations in the African peoples regarding the self-determination of peoples to maintain their culture and cultural objects. (15)

Kwame Tua Opoku.

Mask n’domo,Marka,Mali, now in Musée des Arts Africains,Océaniens et Améridiens (MAAOA)Marseille ,France.

NOTES

1. K. Opoku, Macron Promises To Return African Artefacts In French Museums: A ...

https://www.modernghana.com/.../macron-promises-to-return-afr...

2. K. Opoku, Nigeria Demands Unconditional Return Of Looted Artefacts: A Season ... https://www.modernghana.com/.../nigeria-demands-unconditiona...

3. Quai Branly-Jacques Chirac Museum in Paris is ready to return African art Quai Branly-Jacques Chirac Museum in Paris is ready to return African ...

theartnewspaper.com/.../ethnographic-museum-ready-to-return-a..

Stéphane Martin : «L'Afrique ne peut pas être privée des témoignages ...

www.lefigaro.fr › Culture

PressReader - Le Figaro: 2017-12-07 - « L'Afrique ne peut pas être ... https://www.pressreader.com/france/le-figaro/.../2821535866141..

François de Labarre, Comment restituer le patrimoine africain ? Paris Match| Publié le 08/01/2018 à 05h23 www.parismatch.com/.../Comment-restituer-le-patrimoine-africai .

See also the article by Yves-Bernard Debie , who argues that Macron’s statement would lead to many legal problems and to that extent the hopes and promises raised cannot be fulfilled. «Restituer le patrimoine africain»: l'intenable promesse d'Emmanuel ... www.lefigaro.fr › VOX › Vox Societe

4. Michel Leiris, Phantom Africa, translated by Brent Hayes Edwards, Seagull Books, 2017.

5. Sally Price, Paris Primitive: Jacques Chirac’s Museum on the Quay Branly University of Chicago Press, 2007. See also K. Opoku , The Logic of Non-Restitution of Cultural Objects from the Musee du quai Branly... - Afrikanet.info www.afrikanet.info › Home › African Ar

6. Sally Price, ibid. p.123.

7. Sally Price, ibid. p.124.

8. Sally Price, ibid. p.125.

9. ‘ Personnellement je ne vois aucune objection de principe à des transferts de propriété, après la définition d’un vrai projet scientifique et culturel. A cela, des voix africaines vont s’opposer, disant que c’est du néocolonialisme. Aujourd’hui, l’action culturelle se fait à l’échelon international. C’est ce qu’on fait quand on restaure une œuvre d’art. Quand on réencadre “La Joconde”, le Louvre crée une commission internationale. Si demain un musée africain crée les conditions pour exposer une collection, je serais très heureux de voir une partie des objets repartir là-bas.’ Paris Match

10. ‘Il ne faut pas voir l’œuvre, mais le projet. Il ne faut pas voir la France et ses anciennes colonies mais un continent qui veut reconstituer son patrimoine et la communauté internationale qui serait prête à l’aider. Il faut que ce soit une envie moderne et pas tournée vers le passé. C’est ce qui me gêne dans le mot “restitution’. Paris Match.

11. ‘ Il faut laisser à ceux qui récupèrent les œuvres le soin et le temps de trouver les solutions qui leur conviennent’. Restitutions « Il faut y aller dans la joie, EN TRIBUNE, LE MONDE ·SAMEDI 13 JANVIER 2018.

12. Louvre Abu Dhabi: Jean Nouvel's spectacular palace of culture ...

https://www.theguardian.com › Arts › Art & design › Architecture

Critical Round-Up: The Louvre Abu Dhabi by Jean Nouvel | ArchDaily

https://www.archdaily.com/.../critical-round-up-the-louvre-abu-d ..

The Louvre - United Arab Emirates - Art - The New York Times

www.nytimes.com/2007/03/07/arts/design/07louv.html

K. Opoku, Stolen Art Objects From One “universal Museum” -Louvre Paris To ... https://www.modernghana.com/.../stolen-art-objects-from-one-un ...

13. Benin wants old ruler France to return thousands of colonial treasures ...

www.scmp.com › News › World › Africa

La France refuse de restituer au Bénin ses biens culturels pillés durant ...

tellmemoretv.com/la-france-refuse-de...au-benin.../4116

Le Bénin demande à la France de lui restituer ses trésors pillés - NOFI

nofi.fr/2016/08/benin-france-tresors-pilles/30483

Refus de la France de restituer des biens culturels du patrimoine ...

https://africaction.wordpress.com/.../refus-de-la-france-de-restitue ..

14. Jean- Jacques Breton gives in his, Idées reçues sur les arts premiers (Editions Cavalier Bleu, 2013) some very useful information on where to find non-European arts in France. He states there are at least 220 such museums in France. A very useful link mentioned by Breton is www.museoartpremier.com a database listing collection of non-European artefacts kept by French museums.

15. Kwame Opoku – Defence of “Universal Museums ” Through Omissions and Irrelevancies ...

https://www.toncremers.nl/kwame-opoku-defence-of-universal- ...

Declaration On The Importance And Value Of Universal Museums ...

https://www.modernghana.com/.../declaration-on-the-importance ...

Kwame Opoku - Europeans and American Museums Directors and Legality...

www.afrikanet.info › Home › Latest News › Latest

Kwame Opoku: Dr. Cuno Again - Reviving Discredited Arguments To ...

www.africavenir.org/.../kwame-opoku-dr-cuno-again-reviving-d ..

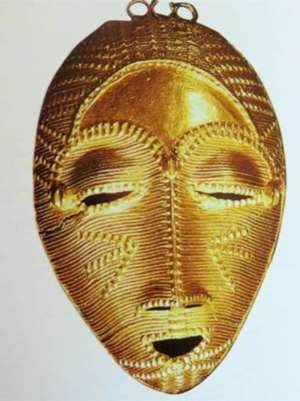

Fang mask, Gabon now in Musée du quai Branly, Paris, France.

Burkina Faso expels French diplomats for 'subversive activities'

Burkina Faso expels French diplomats for 'subversive activities'

GOIL reduces petrol price by 29 pesewas, sells GHC14.70 per litre

GOIL reduces petrol price by 29 pesewas, sells GHC14.70 per litre

The disrespect towards security is terrible; we can do better — Atik Mohammed co...

The disrespect towards security is terrible; we can do better — Atik Mohammed co...

Starlink to cease connection in Ghana, other “unavailable” countries on April 30...

Starlink to cease connection in Ghana, other “unavailable” countries on April 30...

MMCEs, DCEs and Regional Ministers must be elected to reduce political interfere...

MMCEs, DCEs and Regional Ministers must be elected to reduce political interfere...

National Cathedral: ‘Nonsense; you take taxes from broke Ghanaians to dig a clum...

National Cathedral: ‘Nonsense; you take taxes from broke Ghanaians to dig a clum...

April 18: Cedi sells at GHS13.59 to $1, GHS13.01 on BoG interbank

April 18: Cedi sells at GHS13.59 to $1, GHS13.01 on BoG interbank

We must harness the collective power and ingenuity of female leaders to propel o...

We must harness the collective power and ingenuity of female leaders to propel o...

Saglemi Housing Project will not be left to rot – Kojo Oppong Nkrumah

Saglemi Housing Project will not be left to rot – Kojo Oppong Nkrumah

Asantehene commends Matthew Opoku Prempeh for conceiving GENSER Kumasi Pipeline ...

Asantehene commends Matthew Opoku Prempeh for conceiving GENSER Kumasi Pipeline ...