‘… our research methods resemble the interrogations of an investigating magistrate much more than amicable conversations, and because, nine times out of ten, our methods of collecting objects involve forced purchases, if not requisition. All this casts a certain shadow over my life, and my conscience is only halfway clear. When all is said and done, as much as adventures like the taking of the kono finally leave me without remorse, because there is no other way to obtain such objects and because sacrilege itself is a rather grandiose notion, still all this constant buying leaves me perplexed, because I have a strong impression that we are going in vicious circle: we pillage the Negroes under the pretext of teaching people to understand and appreciate them-that is, ultimately in order to mold other ethnographers who will go in turn to ‘’appreciate’’ and to pillage them…’ - Michel Leiris, Phantom Africa (1)

Amongst the various decisions on restitution adopted in months, the adoption of a policy on ethical returns by the Smithsonian is surely one of the most remarkable. (2)

Those who have followed discussions on restitution of looted artefacts in previous decades would immediately recognize the tremendous importance of such a policy and its potential ramifications. One argument that was usually presented to demanders of restitution of looted artefacts was that however deplorable the circumstances of acquisition of an artefact may be from a moral or ethical standpoint, once the object has been legally acquired, there was no objection to a museum holding on to the object. Practically, all Western museums and their directors adopted this stance.

This position is illustrated by the document pompously entitled Declaration on the Importance and Value of Universal Museums (3) adopted by eighteen major museums, not including the British Museum, in 2002, by which they declared that artefacts in their collections, however acquired, had become part of the culture of the countries where the museums were situated:

‘The international museum community shares the conviction that illegal traffic in, artistic, and ethnic objects must be firmly discouraged. We should, however, recognize that objects acquired in earlier times must be viewed in the light of different sensitivities and values, reflective of that earlier era. The objects and monumental works that

were installed decades and even centuries ago in museums throughout Europe and America were acquired under conditions that are not comparable with current ones.

Over time, objects so acquired—whether by purchase, gift, or partage—have become part of the museums that have cared for them, and by extension part of the heritage of the nations which house them. Today we are especially sensitive to the subject of a work’s original context, but we should not lose sight of the fact that museums too provide a valid and valuable context for objects that were long ago displaced from their original source.’

These artefacts acquired through violence or stealth had been accepted as legally acquired and the major museums wanted to discourage any demands for restitution.

Many Western scholars adopted directly or indirectly this. Thus, most writers admitted that, for example, the manner Benin artefacts were acquired, through the British invasion of Benin in 1897 was deplorable but, according to this way of thinking, International Law did not prohibit the taking of loot by victorious powers. Most western domestic laws recognized the right of plunder. The violent invasion of Benin by the British army was deplored by many, but the subsequent stealing of Benin artefacts was approved by the Western world. John Picton, for example stated:

“The moral argument in favour of Benin City remains nevertheless, not least because the looting of its art is not in dispute, which suggests that some kind of compromise ought to be possible. Here are some suggestions: the recognition by the museums of Europe and America that they do not have unproblematic ownership rights to this material—some recognition, indeed, that the king of Benin might have a case. (4)

The Smithsonian adopted on 29th April a policy on ethical returns which brings back moral considerations to the question of restitution:

We believe that past acquisitions raising ethical concerns should be investigated and addressed in a manner consistent with current ethical standards.

We value being proactive rather than simply responsive in addressing issues related to past collecting. We will work in partnership with individuals and communities, as well as with inter-governmental and regional stakeholders, regarding the care and potential return of human remains and/or objects of tangible cultural heritage in Smithsonian collections, including sharing associated information, not only when legally required but when ethically obligated, advocating thoughtful engagement with communities and mutual knowledge-sharing and capacity building. (5)

In the past when issues arose over Western Museum collections, the response was usually that museums were legal owners and therefore entitled to keep them. The new policy statement makes it clear that morality must prevail over legality on questions of ownership and that the to be applied must be present moral standards and not old standards and rules. This clearly puts an end to one of the favourite arguments of Western museums when faced with moral dilemmas: these acquisitions were legal in the olden days. We cannot apply the standards of today to events of the past, it was argued.

The Smithsonian has already promised to return its 39 Benin bronzes but said nothing about other looted African artefacts it holds. It is amazing how Western museums, and their governments act as if the question of restitution of looted African artefacts concerned only Benin. Many museums have explained what their policies are concerning restitution of Benin artefacts as if that were the only issue. Egyptian, Ethiopian, Egyptian and Asante treasures are forgotten! We recall that Western museums hold large numbers of other African artefacts such as Asante gold treasures, Ife and other Yoruba treasures, Igbo artworks, Nok objects, Ethiopian gold, and silver works.

One could also mention many thousands of African treasures stolen during the colonial period such as Baga, Baule, Chokwe, Dogon, Nok, Fang, Fon, Idoma, Kuba, Luba, Mamuye, Mangbetu, Mossi, Pende, and Urhobo artworks. Africa is a continent and not a village!

Smithsonian has fundamentally undermined allegedly solid arguments used by Western museums to fend off demands by African States and peoples for the restitution of their looted artefacts in Western museums.

The new policy of the Smithsonian is to be applied by each of its twenty-one institutions in a way adapted to its own needs and there is no declared intention to investigate systematically the inventories of all institutions for artefacts acquired under dubious circumstances. The impact of these new principles may in practice, therefore, be more limited than we assume and there could be longer delays in dealing with the issue as it affects each looted item in the Smithsonian. Nevertheless, the direct introduction of ethical principles into issues of restitution of looted artefacts is itself a great advance on the debates as have so far prevailed. A Belgium study has also proposed moral standards in this area:

‘Although the existing legal framework is not favourable to the original owners of the objects in colonial collections, there are opportunities for change. Indeed, the law should try to be in tune with the social and ethical issues of its time, reflecting the demands for equity and reconciliation with the past that are increasingly resonating within society. A moral duty to return the colonial heritage is emerging, inviting us to go beyond the limitations of the existing legal framework in order to make an ethical responsibility heard in law.’ (6)

Most Western States and their museums are not moved by such moral considerations.

Smithsonian’s change of position, however welcome, comes after so many other institutions have returned or promised to return looted African artefacts in their collections.

The Germans are returning 1130 Benin artefacts to Benin, Nigeria. (7) The French have returned recently to the Republic of Benin twenty-six looted artefacts, but this has not affected in anyway the fundamental and traditional rules of French law which prevent restitution. French law still maintains its principle of ‘inalienability,’ to protect thousands of looted artefacts in their museums including those looted in the colonial period that the Sarr-Savoy report recommended should be returned to their owners. The restitutions to the Republic of Benin were thus exceptions to the general rule that restitution of objects forming part of State property requires specific legislation. (8)

The Dutch are in the process of examining legislation that would permit restitution of looted African artefacts. (9) The Belgians have before their legislature a general legislation that would enable a large- scale restitution to the Republic of Congo. (10)

The British Museum and the British Government have unperturbably continued as usual and do not seem bothered by any of the considerations that led the Smithsonian to recently adopt its policy on ethical returns. The impressive efforts and decisions of Germany and other European States to reconsider their policies of restitution of looted African artefacts have not affected the British Museum’s negative position on restitution. Neither the recent views of Neil MacGregor on the ‘universal museum’ nor the withdrawal by London Times of support for the British Museum’s denial of restitution of the Parthenon Marbles has had any effect. The venerable museum in Bloomsbury continues with its half-truths, misleading and deceptive statements. (11) The Victoria and Albert Museum that keeps illegally hundreds of Asante gold works as well as looted Ethiopian treasures from the British invasion of Maqdala in 1868, has stubbornly follows the British Museum in the refusal to restitute. Nevertheless, several institutions in Britain have adopted various positions and returned Benin artefacts. Jesus College, Cambridge University, and University of Aberdeen have recently returned each a Benin bronze to the Oba of Benin, Nigeria. (12)

Many American museums have either returned artefacts or are in the process of doing so.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art has returned three Benin artefacts to Benin but has said nothing about the other 160 Benin artefacts it holds, including the famous Queen-Mother Idia hip mask that is important for Benin history. According to the Washington Post the following museums have stated they are in discussion with the Nigerian authorities-Penn Museum, Field Museum, Stanley Museum at the University of Iowa, Baltimore Museum of Art, New Orleans Museum of Art, Newfields in Indianapolis, and the Toledo Art Museum. Other museums have said they will be willing to restitute if Nigerian officials put in a request. (13)

With respect to Nigerian authorities asking museums for restitution of looted objects, we should recall that there is a long history of Nigeria doing just that without any effect. The Oba of Benin sent a request in 2009, hand-carried by a Benin princess to Chicago, to both the Field Museum and the Art Institute of Chicago, then under director James Cuno. There was no response to the Royal request from the Field Museum or from the Art Institute where a magnificent Benin exhibition, Benin Kings and Rituals, Court Art from Nigeria was being held and Cuno had promised to consider a request for restitution. (14) The Field Museum holds four hundred Benin artefacts.

Whatever may have been the factors and considerations that finally led the Smithsonian to adopt a policy of ethical returns that puts into question Western museums’ acquisitions policies of hundred and more years, the American institution has touched on the weakest edge of Western morality and museology. However, the respectable American institution did not go all the way. It has not announced a decision to examine all its holdings to find out what objects have been acquired in the past under dubious circumstances even though the institution is aware that some of its items may have been looted. But artefacts derived from past practices are to remain and are not subject to any systematic examination even though the Smithsonian has declared: We believe that past acquisitions raising ethical concerns should be investigated and addressed in a manner consistent with current ethical standards.

Results of past unethical methods of acquisition must be corrected. Promise that the institution will in future not follow the wrong methods of the past is not enough. The present imbalance of distribution between African museums and Western museums comes from unethical methods of the past and if this is not to be corrected systematically, then all discussions on ethical standards will not change much. Past acquisitions are present possessions, and the current discussions are primarily about present holdings that are explained by past acquisitions. One cannot separate the past from the present in this matter. It would otherwise be an extremely easy problem.

No reasons were given for not taken what would have been a logical step: examine all acquisitions. Finance could not have been the main cause since Smithsonian is one of the richest institutions in the world. It holds 155 million objects in all institutions. But could one seriously advance the considerable number of artefacts as ground for not carrying a thorough provenance research?

The Smithsonian declares that past acquisitions raising ethical concerns should be investigated and promises to be proactive when requests are submitted for restitution but why wait until requests are made? Knowingly sitting on thousands of stolen properties and waiting until the uninformed owners demand their return does not appear particularly ethical. Everybody knows that Africans are not aware of the whereabouts of thousands of their artefacts stolen during the colonial period. Only those Africans who are lucky enough to visit Western museums see such artefacts. They must have the financial resources and obtain visa for Western States that practice racial discrimination and do not encourage Africans to visit their countries. Indeed, Western countries are busy expelling Africans who do not have legal documents.

The word ‘provenance’ which features so often in Western European discussions on restitution is not prominent in the Smithsonian statement on ethical returns. The best the Smithsonian could do, if the ethics of restitution are taken seriously, would be to examine systematically its holdings and return unconditionally to their rightful African owners objects acquired with violence or under dubious circumstances. Given the traumatic and tragic experience of the African peoples, on the Continent and in the Diaspora in the Americas and in Europe, it is surely not too much to expect the Smithsonian to conduct a thorough investigation of its holdings and to expunge dubious acquisitions.

The introduction of ethical considerations into matters of restitution of looted African artefacts will no doubt render untenable, arguments presented by holders of artefacts acquired under dubious circumstances. Their own public in the West will urge them to uphold ethical principles and pave the way for better relations with countries that are still recovering from the evils of slavery, colonialism, and racism.

A new era of ethical relationship would imply an atmosphere of openness and the end of unnecessary secrecy in matters of public interest such as restitution of looted artefacts. It would no longer be enough for Western museums to say they are discussing with Africans. They must tell the public what they are discussing with African representatives.

Western museums would have to adapt their language and speak more in the indicative mood and less in conditional mood when it comes to restitution.

There must be a separation of the legal rights of ownership from the actual location of artefacts. Legal rights should immediately be transferred by Western museums to the African States. Negotiations should be started on loans of artefacts by the African museums to Western museums, including the terms of the loans and the relevant fees. These loan fees are to be distinguished from the major question of what compensation Western States and their museums should pay for keeping illegally for hundred years African artefacts and thus depriving Africans of the use and enjoyment of their property as well as loss of earnings by African museums.

The period of illegal holding of looted artefacts must be ended in order for both Africans and Westerners to freely enter into relationships of mutual benefit. African artefacts in Western museums will no longer be looted artefacts but treasures on loan from African States to Western museums. Only then can we think of free relationships, devoid of any imbalance of power or possessions. Symbolic gestures of returning one or two artefacts will not do. Nor should Western museums think we Africans do not see the games they are playing by keeping the best African artefacts or most historically relevant objects while returning less significant items to Africa.

Will the Smithsonian, and other Western museums that in the past have paid scant attention to United Nations/UNESCO resolutions now be disposed to examining and following the demands of the world institutions? Since 1973 the General Assembly has been passing a resolution entitled Return or Restitution of Cultural Property to the Countries of Origin. Many in the West argue that the resolutions of the General Assembly have no legally binding force but at most a morally persuasive force as the voice of the majority of States. Legally binding force is, according to this view, reserved for Security Council decisions. An ethically inclined policy will pay attention to the resolutions of the international institutions that contain the main requirements of morality and ethics.

We do not know what general system of ethics underlies the Smithsonian’s introduction of ethics into the question of restitution but whatever system is in operation, all will agree that Western museums have failed woefully in this area, in their dealings with peoples of non-European descent. Museums have acquired millions of African artefacts that were looted with violence or acquired under dubious circumstances. Shame seems to have disappeared from relations with the peoples who looted or ‘collected’ many objects, including children’s toys that were wrenched with violence. Phantom Africa by Michel Leiris details the methods used by Western agents and scholars to deprive Africans of their valuable artefacts. (15)

Despite all the evidence on the brutal and violent methods used by the colonialists to acquire African artefacts, Western museums no matter what they say, are not in a hurry to return looted African artefacts after more than hundred years of illegal detention.

“It is especially difficult to procure an object without at least employing some force. I believe that half of your museum consists of stolen objects.”

Richard Kandt, Resident of the German Empire in Ruanda to Felix Luschan. (16)

Kwame Opoku.

NOTES

1.Leiris letter to Zette, September 19,1931 cited at p.163 in Phantom Africa by Michel Leiris, translated by Brent Hayes Edwards, Seagull Books, 2017. Those seriously interested in the question of African artefacts looted by the colonial powers should read Phantom Africa where the methods used by Western agents in their collection of artefacts in the colonies are fully described.

Leiris was secretary-archivist to the notorious French expedition mission, Dakar-Djibouti -Mission, 1931-33, under the leadership of Marcel Griaule that went across Africa collecting and stealing with French authority, artefacts from several African countries. The mission came back to Paris with over 3500 artefacts that were first kept in Musée de l’Homme and in the Musée des Arts Africains et Oceaniens. The items were transferred to Musée du Quai-Branly-Jacques Chirac when it was created in 2006.

An indispensable book on ethics and colonialism is Adam Hochschild, King Leopold’s Ghost: A Story of Greed, Terror, and Heroism in Colonial Africa, Mariner Books, 1998.

2. Smithsonian, The Values and Principles Statement. https://www.si.edu/newsdesk/releases/smithsonian-adopts-policy-ethical-returns

3. Lyndel V. Prott (ed.) Witnesses to History A Compendium of Documents and Writings on the Return of Cultural Objects, UNESCO,2009.

K. Opoku, Declaration on The Importance and Value of Universal Museums: Singular Failure of an Arrogant Imperialist Project

https://www.modernghana.com/news/441891/1/declaration-on-the-importance-and-value-of-univers.html

https://ia801608.us.archive.org/11/it..Importance%20and%20Value%20of%20Universal%20Museums.pdf

Neil G. W. Curtis, Universal museums, museum objects and repatriation: The tangled stories of things. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/09647770600402102

Tom Flynn, The Universal Museum- A valid model for the 21st century? Lulu, 2012. Lulu.com

4. Compromise, negotiate, support, Art Newspaper,24 January 2011.

K. Opoku, Compromise on the Restitution of Benin Bronzes? Comments on Article by Prof. John Picton on Restitution of Benin Artefacts

5. Smithsonian, The Values and Principles Statement. https://www.si.edu/newsdesk/releases/smithsonian-adopts-policy-ethical-returns

6. Ethical Principles for the Management and Restitution of Colonial Collections in Belgium, 2021. https://restitutionbelgium.be/en/repor

7. Deutsche Welle, Germany to begin returning Benin Bronzes in 2022

https://www.dw.com/en/germany-to-begin-returning-benin-bronzes-in-2022/a-%20Forum.

The Guardian, Germany first to hand back Benin bronzes looted by British. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/apr/30/germany-first-to-hand-back-benin-bronzes-looted-by-british

The Arts Newspaper, And so it begins: Germany and Nigeria sign pre-accord on restitution of Benin bronzes

8. K. Opoku, France Moves Closer to Restitution of Artefacts to Benin and Senegal https://www.modernghana.com/amp/news/1019889/france-moves-closer-to-restitution-of-artefacts.html

Felwine Sarr and Bénédicte Savoy, The Restitution of African Cultural Heritage. Toward a New Relational Ethics http://restitutionreport2018.com/sarr_savoy_en.pdf

9. K. Opoku, Dutch Are Taking Giant Steps Towards Restitution of Looted Artefacts https://www.modernghana.com/news/1043306/dutch-are-taking-giant-steps-towards-restitution.html

10. Ethical Principles for the Management and Restitution of Colonial Collections in Belgium, 2021. https://restitutionbelgium.be/en/repor

11. K. Opoku, How Long Will the British Government and The British Museum Resist Calls for Changes in Restitution Policy? https://www.modernghana.com/news/1135499/how-long-will-the-british-government-and-the-briti.html

According to the Arts Newspaper, the British delegation to UNESCO’s Intergovernmental Committee has been trying to discuss the issue of the Parthenon Marbles with the Greek delegation, with contradicting messages coming from the British Governmental Department for Digital, Culture, Media, and Sport. This contradicting messaging may not be accidental but deliberate. This game of ping- pong has ben going on for decades since 1833 when the Greeks started demanding the restitution of the Parthenon Marbles that were illegally carted away from Athens by the then British Ambassador to Athens, Lord Elgin. He later sold the items to the British Parliament that in turn donated them to the British Museum. The British Government often says that it is a matter for the British Museum and the British Museum says there is need for new laws in order to return the objects to Athens. The British have had enough time to determine who has authority to deal with Parthenon Marbles if they wanted.

In the meanwhile, the British public has voted consistently in all public opinion polls overwhelmingly in favour of returning the artefacts to Athens. We see here what the ‘democratic’ British Government thinks of its own public opinion. Britain’s major messaging failure on Parthenon Marbles (theartnewspaper.com)

Readers should have a look at the homepage of the British Museum which transmits a deceptive and misleading view of the present issues relating to the Benin artefacts. Benin Bronzes | British Museum

12. Benin bronze: 'Looted' Nigerian sculpture returned by university

https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-scotland-north-east-orkney-shetland-59063449.

Jesus College returns Benin Bronze in world first

Jesus College returns Benin Bronze in world first | Jesus College in the University of Cambridge

13. U.S. museums are trying to return hundreds of looted Benin treasures https://www.washingtonpost.com/arts-entertainment/2022/05/11/benin-treasures-museum-returns/

14. K. Opoku, Benin Exhibition In Chicago: Cuno Agrees To Consider Request For Restitution Of Benin Bronzes (modernghana.com)

15. K. Opoku, Who Is Afraid of Phantom Africa?

https://www.modernghana.com/news/800468/who-is-afraid-of-phantom-africa.html

16. “, Dass der Erwerb von Ethnographica in der Kolonialzeit auf der Grundlage mehr oder minder “struktureller Gewalt” erfolgte, soll hier in diesem Rahmen nicht näher verfolgt werden. Einzelnen Zeitgenossen war diese Tatsache im Übrigen durchaus bewußt. So schrieb der Afrikareisende und Resident des Deutschen Reiches in Ruanda, Richard Kandt, 1897 an Felix von Luschan, den stellvertretenden Direktor des Berliner Völkerkunde-Museums: Überhaupt ist es schwer, einen Gegenstand zu erhalten, ohne zum mindesten etwas Gewalt anzuwenden. Ich glaube, daß die Hälfte Ihres Museums gestohlen ist“.

Cornelia Essner, Berlins Völkerkunde-Museum in der Kolonialära: Anmerkungen zum Verhältnis von Ethnologie und Kolonialismus in Deutschland in: Berlin in Geschichte und Gegenwart- Jahrbuch des Landesarchivs Berlin, (Ed.) Hans J. Reichhardt, Siedler Verlag, 1986, p.77.

Benin warriors, Benin, Nigeria now in National Museum of African Art, Smithsonian Institution, USA.

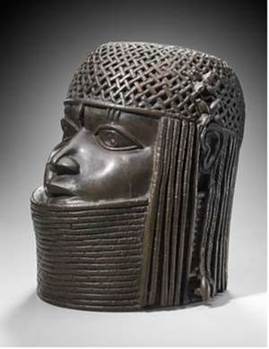

Commemorative head of an Oba, Benin, Nigeria, now in National Museum of African Art, Smithsonian Institution, USA.

Benin warriors, Benin, Nigeria, now in National Museum of African Art, Smithsonian Institution, USA.

Sabre, Akan afena, Côte d’Ivoire, now in National Museum of African Art, Smithsonian Institution, USA.

Oba with two attendants holding his arms, Benin, Nigeria, now in Field Museum, Chicago, USA.

Chief's attendant blowing a side-horn Benin, Nigeria, now in Field Museum, Chicago, United States of America.

Queen-Mother pendant mask Iyoba,Benin,Nigeria,now in Metropolitan Museum of Art,New York,USA.

Oba on a horse with his attendants, Benin,Nigeria, now in Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, USA.

Saltcellar with Portuguese figures, Benin, Nigeria, now in Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, USA.

Head of an Oba, Benin, Nigeria, now in Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, USA.

Altar ivory tusk, Benin, Nigeria, now in Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, USA.

Egungun mask, Yoruba, Nigeria, now in Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, USA.

Equestrian, Soninke, Mali, now in Metropolitan Museum, New York, USA.

Royal Seat, lupona, (female caryatid), Luba, Democratic of Congo, now in Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. USA.

Portuguese soldier with gun, Benin, Nigeria, now in Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, USA.

Pendant depicting an Oba and two dignitaries, Benin, Nigeria, now in Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, USA.

Head of an Oba, Benin, Nigeria, now in Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, USA.

Relief plaque showing a dignitary playing a drum with two attendants playing gong, Benin

Nigeria, now in Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, USA.

Pendant depicting a queen-mother playing gong, Benin, Nigeria, now in Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, USA.

Noble warrior, Benin, Nigeria, now in Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, USA.

Triptych icon depicting Virgin Mary and child Jesus, flanked by archangels Gabriel and Michael, Ethiopia, now in Art Institute of Chicago, USA.

Headdress, Chi Wara Bamana, Mali, now in Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, USA.

Royal Chair asipim, Asante, Ghana, now in Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, USA.

We’ll protect state wealth from opaque deals – Prof Jane Naana

We’ll protect state wealth from opaque deals – Prof Jane Naana

Mauritania president says running for second term in June polls

Mauritania president says running for second term in June polls

I won't ever say I was a mere driver’s mate' — Prof. Opoku-Agyemang

I won't ever say I was a mere driver’s mate' — Prof. Opoku-Agyemang

2024 polls: 'EC struggling to defend credibility'— Prof. Opoku-Agyemang

2024 polls: 'EC struggling to defend credibility'— Prof. Opoku-Agyemang

Akufo-Addo gov't's 'greed, unbridled arrogance, unrestrained impunity, sheer dis...

Akufo-Addo gov't's 'greed, unbridled arrogance, unrestrained impunity, sheer dis...

Election 2024: Ghana needs an urgent reset, a leadership that is inspiring – Ma...

Election 2024: Ghana needs an urgent reset, a leadership that is inspiring – Ma...

Partner NDC to rollout a future of limitless prospects – Prof Jane Naana Opoku-A...

Partner NDC to rollout a future of limitless prospects – Prof Jane Naana Opoku-A...

NPP will remain in gov’t till Jesus comes — Diana Asamoah

NPP will remain in gov’t till Jesus comes — Diana Asamoah

Sunyani Technical University demands apology from former SRC president over sex-...

Sunyani Technical University demands apology from former SRC president over sex-...

'Dumsor' was resolved by Mahama but ‘incompetent' Akufo-Addo has destroyed the g...

'Dumsor' was resolved by Mahama but ‘incompetent' Akufo-Addo has destroyed the g...