I read with interest and sometimes, with astonishment the article by Professor John Picton, Emeritus Professor, School of Oriental and African Studies, London, in the Art Newspaper of 24 January 2011, entitled

“Compromise, negotiate, support”. (1)

To start with, I was surprised that Picton describes the British military force, the so-called Benin Pre-emptive Strike Force that went to Benin on 4 January 1897 and was almost annihilated as “British personnel”. “Personnel“evokes in the average English-speaking person, a group of employees other than a military force. One thinks of the personnel of Shell or other British firms in Nigeria or elsewhere. Perhaps the Professor did not reflect on this but he, as a specialist on African art must surely know that this military force consisted of 9 British military officers and some 250 African mercenaries disguised as carriers. The mission of this army was to launch a surprise attack on Benin City, overthrow Oba Ovonramwen and put in his place an Oba amenable to British imperialism. Frank Willet, in writing about this military force, said they had their guns at the bottom of their boxes. (2) What Picton does not mention but would have painted a more accurate picture of the situation is that the Oba had stated clearly, when informed of the intention of the British to send a group to visit him, that he could not receive them at the time proposed because he would be involved in some traditional rituals and during that period no foreigners were allowed to come into contact with the Oba. Thus the group went to Benin despite the warning from Benin not to come. Since when do we visit monarchs when they expressly state their inability or unwillingness to receive us?

But why did the military force visit Benin despite warnings not to come? It would appear, from messages sent to the British Foreign Office by Captain Phillips, acting Consul-General that a decision had been taken long ago, reflecting the view of Captain Phillips that Oba Ovomramwen constituted the main obstacle to British imperialist expansionist designs in that part of West Africa and that his removal was imperative if the British were to achieve their aims. So the military force Picton calls British personnel was not an innocent group killed by “rebel chiefs in the area”. It was an army that intended to surprise the Oba but were themselves surprised. (3)

Picton states that Eweka II set about to rebuilt Benin City when he was made Oba: “Eweka set about the wholesale reinvention of Benin City, reviving its ritual and ceremonial culture, making the best of such political authority as the colonial overlords would allow within their policy of government by indirect rule, and commissioning the writing of an authorised history of the city, kingdom and empire, by a local chief. Eweka also commissioned new works of art, setting up altars dedicated to his father and grandfather, and their predecessors: the artists, after all had not been exiled nor their skills somehow taken away from them. It was altogether the greatest and most successful of all anti-colonial projects in sub-Saharan Africa.”

I have serious difficulty in understanding Picton's characterization of the renewal projects by Eweka as “anti-colonial”. The Oba must have believed in the need to set up “altars dedicated to his father and grandfather, and their predecessors” Why must the performance of such a filial duty that Africans expect of their rulers be considered as “anti- colonial”? Most of us will understand by “anti-colonial” activities directed against the colonial authority and intended to bring about the downfall of that regime or at least to hasten its demise. From where did Picton get this idea that rebuilding Benin City, after the wanton destruction by the British in 1897 was an “anti-colonial project”?

It should be noted that to this day the British have not paid any compensation for the killing of thousands of innocent children, women and men as well as for the destruction of property in that city.

We leave uncommented the objectionable habit of describing many areas of Africa as “sub-Saharan”, even though many parts of Africa are by means near the Sahara Desert in any sense. (4)

My great surprise was to see that Professor Picton also subscribes to the idea propagated by many supporters of the detention of the cultural artefacts of others that the original owners have not asked for their return even though all the records show that there have been constant reclamations for these objects.

Picton states “Yet there has been no formal request by a competent authority for the repatriation and no attempt at diplomatic negotiation, or even litigation”.

The people of Benin have been asking for the restitution of their artefacts which constitute an essential part of their culture for a very long time without success.

Picton himself states that “The prestige of kingship and the ownership of works of art are indeed so intertwined that it should come as no surprise that there is hunger in Benin City for the return of the material looted in 1897”

It is rather disappointing that Professor Picton who has written extensively on African art, including African textiles, should also echo the worn-out argument that there has not been any formal demand for the Benin artefacts by a competent authority. (5)

For the benefit of all, we would like to draw attention to the following facts which provide a background against which one may evaluate the tendentious statements often made by Westerners regarding the absence of a formal demand for the restitution of the Benin artefacts.

a) There is no requirement in Municipal or International Law that an owner must first make a formal request to a person who has looted, stolen or illegally taken his property before the wrongdoer can return the object. It is enough that the wrongdoer is informed whereupon he has to act. (6)

b) The United Nations, UNESCO, the Athens Conference on Restitution (2008) as well as the ICOM (International Council of Museums) Code of Ethics require the holder of the cultural property of others to initiate discussions for eventual return of the objects to their countries of origin. (7)

c) The late Bernie Grant, Member of the British Parliament, always reminded the British Parliament and the British public that the people of Benin requested the return of these objects. He also wrote to museums such as the Glasgow Museum. (8)

d) Prof. Tunde Babawale, Director/Chief Executive, Centre for Black and African Arts and Civilization (CBAAC) which was established to perpetuate the gains of FESTAC'77 wrote in 2007 to Neil MacGregor, Director of British Museum, London, asking on behalf of Nigeria and Africa, for the return of the Queen-Idia hip mask in the British Museum. MacGregor responded to the Nigerian professor by a letter which did not even refer to the request and left the demand unaddressed. I am yet to see an explanation or apology for this singularly discourteous behaviour towards Nigeria and Africa. Besides Western commentators, as usually happens when Africans are insulted, do not seem to have noticed this behaviour. (9)

e) Numerous Nigerian governments and Parliament have expressed the wish to have the looted objects returned. These requests were reported by several British media such as the BBC NEWS of 27 March 2002. (10)

f) Prof. Eyo, first Director-General of Nigeria's Commission on Museums and Monuments, has written about the efforts made to obtain the return of a few Benin artefacts at the time of opening the Museum in Benin City and mentions in that context that discussions were held in UNESCO on a resolution to that effect. The Nigerians were persuaded to withdraw the resolution and instead sent letters to all the embassies in Lagos. None of the States thus contacted through their embassies even bothered to reply and consequently sent no artefacts. Photos of the Benin bronzes had to be used at the opening of the museum in Benin City. (11)

g) The Oba of Benin mandated his brother to submit a petition to the British Parliament in 2000. The petition, known as Appendix 21 and the discussion thereon are published in the Parliamentary reports of the British Parliament. (12)

h) Emmanuel N. Arinze, Chairman, West African Museums Programme, also wrote to Julian Spalding, Director, Glasgow Art Gallery and Museum for the return of the Benin bronzes. (13)

i) After the Benin exhibition in Chicago a letter was sent on behalf of the Oba to the Directors of the Art Institute of Chicago and the Field Museum in Chicago requesting the return of some of the Benin bronzes. Up to today, the venerable museum directors have not even bothered to acknowledge receipt of the request. (14)

j) During the recent protests by Nigerians and other Africans against the attempted auction of a Queen-Idia hip mask, the Nigerian authorities reported being in contact with the British authorities to find a solution to the issue of restitution of the looted Benin artefacts. (15)

In view of the above, it becomes difficult to understand the assertion made that there has not been any formal demand by a competent authority for the restitution. One cannot go on forever repeating that there has been no formal demand for the return of the Benin bronzes primarily because such a formal demand is not required by any law and secondly, there have been more than enough formal demands, including letters to the holders of the artefacts and to the British parliament. None of those denying that there have been formal demands has said that they are only waiting for such a demand in order to return the looted objects. Moreover, they are very careful not to say exactly how this formal demand should look like. In other words, this argument is a ploy to wave off all possible demands. If a demand to the British Museum and to Parliament is not enough, what else remains for the holders to do? The pity though is that many intelligent persons do not seem to realize that the argument of there being no formal demand is simply a refusal to come to grips with the issue and a determination to continue the illegitimate detention of the cultural artefacts of others. (16)

I do not know how familiar Picton is with litigation but to suggest somehow that the absence of litigation with regard to the Benin artefacts is surprising, is to ignore the particular nature of the case and the particular circumstances leading to the loss of the artefacts. This is not a kind of situation envisaged for the normal legal system. A European government going all the way from Europe to Africa to cause wanton destruction and steal/loot the artefacts of the Africans is clearly a matter beyond the courts for true justice. Insofar as the artefacts are objects of property rights, there may be situations where it would be necessary to institute legal proceedings but for the solution of the general question of restitution, litigation is not the best solution. As Picton knows, there have been recently many restitutions to Egypt. Ethiopia, Italy and Peru without resort to litigation. Why must Benin restitution involve litigation?

Picton throws in the idea that the Benin bronzes are in so many museums in America and Europe and that this creates a complex situation for litigation. He seems to forget that only one entity was responsible for the looting of the Benin artefacts: Government of Great Britain that sent armed forces to attack Benin and later sold the artefacts to others. Those who bought the artefacts from the British, such as the Germans, Austrians and Americans could of course be considered as accessories for they all knew that the artefacts were stolen objects recently looted from Benin. Indeed, the auctioneers always mentioned this fact to potential buyers who were invited 5 months or so after the invasion to purchase.

I was happy to read the following from John Picton:

“The moral argument in favour of Benin City remains nevertheless, not least because the looting of its art is not in dispute, which suggests that some kind of compromise ought to be possible. Here are some suggestions: the recognition by the museums of Europe and America that they do not have unproblematic ownership rights to this material—some recognition, indeed, that the king of Benin might have a case; the loan of material from reserve collections for display in Benin City, whether of a temporary or permanent basis; travelling exhibitions in which some of the great museums—the British Museum, The Museum of Ethnography at Berlin's Dahlem complex, New York's Metropolitan Museum of Art, for example—might collaborate so that Nigerians get to see this material in Nigeria”.

It is encouraging that Picton has adopted the idea of a compromise. Many have been thinking along these lines even though they have avoided the word “compromise” since it has unacceptable connotations. All who have argued for restitution of the Benin bronzes, including the present writer, have suggested that a solution ought to be possible given that the basic facts of the case are not disputed by anyone or as Picton puts it, “the looting of the art is not in dispute”.

The real question is what kind of solution or compromise? Picton has made some suggestions which differ from our own. He refers to “the recognition by the museums of Europe and America that they do not have unproblematic ownership rights to this material.” In view of the undisputed historical facts and the violence involved in the looting, we would rather suggest that there should be recognition by the governments and museums of Europe and America that their privileges of possession are tainted with illegitimacy ab initio.

What kind of objects ought to be transferred to Benin? Picton is thinking of “the loan of material from reserve collections for display in Benin City”. We think that the objects to be returned to Benin should not be on loan but a straightforward return to the original owners. Either we agree on the historical facts of the situation or we do not. Picton should not state that the facts are not in dispute and turn round and write as if Benin were a beggar. Benin is not seeking a loan, permanent or temporary but the restoration of its rights. Furthermore Picton writes that the objects should come “from reserve collections“of the museums. We do not accept this. First of all, for a proper compromise, the museums, especially the British Museum, should stop playing cat and mouse games and tell us how many of the Benin bronzes they have had at the beginning and how many remain, after those they have sold or exchanged with others. We still do not have exact figures of the Benin bronzes the British Museum has in its possession nor do we know what is in its reserve. A compromise that should bind future generation must be based on full disclosure of the facts. Picton knows that the most coveted Benin pieces such as the Queen-Idia hip mask are on display and not among the reserve collection. Thus his suggestion to give to Benin objects from reserve collection would ensure that the best pieces remain with Western museums.

A few weeks ago, when writing about the abortive auction of the Queen Mother-Idia mask, Picton criticised Prof. Peju Layiwola, (a descendant of the legendary Oba Ovonramwen from whose palace the Benin bronzes were looted) who had suggested that we need exact figures about the Benin artefacts that were looted. Picton stated:”The location of almost all works of art from Benin City is published public knowledge. The argument in favour of repatriation is not helped by rhetorical questions and inaccurate data”. With all respect to the emeritus professor, hardly anybody knows exactly how many of the Benin bronzes are in the possession of the British Museum. Philip J.C. Dark's An Illustrated Catalogue of Benin Art (1982) published almost thirty years ago is out of print and not easily available to those working in non-Western countries. Besides, can a book published thirty years ago on such matters as the locations of the Benin artefacts be still up to date? What about sales and exchanges of the objects by the museums? Clearly, accurate figures, even though not absolutely necessary for commencing the restitution process if there is goodwill, will be immensely useful for a just distribution of the objects. Surely, science gains from accurate information. (17)

Once we have full and exact figures of the Benin bronzes, a Committee should be set up including 2 representatives from Britain and 2 representatives from Benin, a representative from United Nations, UNESCO and ICOM. This Committee should do the selection of objects that should go to Benin and those that should remain in the British Museum. The Committee should also work out a formula for division of the objects. Our own formula would be two thirds for Benin and a third of the total for the British Museum. Thus if the museum is now holding 150 objects, 100 would go to Benin and 50 would remain in London. This is suggested on the basis of the historical facts that are not in dispute. Whatever formula is adopted must reflect the historical facts.

Picton, to my surprise again resorts to the worn out argument about the absence of secure facilities for the artefacts that are to be returned to Nigeria.

“The problem here, of course, is that adequate facilities of international standard do not exist in Nigeria. But suppose that a secure display facility were to be built in Benin City that conformed to modern international standards of conservation and climatic control: the moral case would then be very hard to ignore.”

This is a mendacious argument in the arsenal of the retentionists of other people's cultural artefacts and Picton should know that this is no argument against returning artefacts to their countries of origin. And please, let us not talk about climate control with respect to Benin objects. They had been in our West African climate for ages before they were stolen by the British and now people wonder whether there is a right climate in Benin.

For several decades, the British Museum which is detaining the Elgin/Parthenon Marbles had argued that there were no adequate facilities in Athens to house the Marbles. The Greeks built a super modern museum, New Acropolis Museum at Athens only to hear the British Museum Director declare that the question of the location of the Marbles is no longer relevant. What mattered now, according to MacGregor, was how the British and Greeks could show the Marbles to the Chinese and Africans:

“The real question is about how the Greek and British governments can work together so that the sculptures can be seen in China and Africa”. (18)

With regard to this repeated argument about lack of secure facilities in Nigeria and elsewhere, we should bear the following in mind:

a) We are all in favour of secure museums and nobody contests the fact that Nigeria could, and must, improve the conditions of its museums.

b) Stealing from museums is, unfortunately, a practice which occurs everywhere in the world, including the so-called developed countries of the West. Museum Security Network and other internet sites report daily and often hourly, of numerous art thefts in Britain, France, Netherlands and Germany. There are other reports showing that American museums are not secured against fire and water damages.

c) Those Nigerian artefacts that have not been looted by the British or stolen by those encouraged by the Western market, are well cared for as demonstrated in the recent Ife exhibition.

d) All stolen/looted African and other artefacts end up in Western museums or private collections in the West. Is there a link here? Added to this is the preaching of false prophets who argue that the West has a right, if not a duty, to purchase artefacts irrespective of their provenance.

e) The argument on security and facilities could be used to keep forever the looted artefacts of others. Since when is it acceptable that those who have looted artefacts of others can set themselves up as judges and decide that the original owners are not worthy of the objects because they do not have adequate and secure facilities?

f) Does the absence of security and adequate facilities mean then that Nigerians and others are not to continue their cultural development and practices since whatever they have created or create could be detained in the West with the security and facilities argument?

g) When the people of Benin and elsewhere request the return of their looted artefacts, they do so, not on the basis of the facilities they have but simply by virtue of their rights of ownership which even the opponents of restitution do not deny.

h) The questions of ownership must be strictly separated from any other question such as that of security which may be related but cannot be used to negate ownership rights.

i) We have not heard a single Western State or museum declare that they are willing to return Benin objects if Nigeria/Benin had adequate facilities.The issue of facilities is brought up as a supplementary argument to support the determination not to return the artefacts.

j) No system of justice could function correctly by allowing wrongdoers to negate its fundamental principles and rights by virtue of their wrongdoing.

The persistent debate on restitution continues basically because of greed and the desire to control others.

Greed appears to be the driving motor of the so-called “universal museum” such as the British Museum, London, Louvre, Paris, Musée du Quai Branly, Paris, Ethnology Museum, Berlin, and Ethnology Museum, Vienna. These are museums that never have enough of artefacts. Despite the fact that they are constantly complaining about lack of space and resources and have no possibility to display most of the objects in their depots, they still want more artefacts. They do not want to return any of the looted artefacts. The British Museum is reported by the BBC to have some 8 millions of artefacts, some in depots spread across London but the venerable museum is not willing to return one artefact, the Queen-Idia hip mask, at the cost of insulting Nigeria and all other African States. According to the BBC, what is on public show amounts to just 1% of the institution's eight million artefacts. (19)

Coupled with greed is the arrogance of the Western States and their museums acting in the belief that they have a right and duty to control the artefacts of others, especially, the Africans. This belief which is an expression of cultural superiority and a manifestation of cultural imperialism makes it very difficult for Westerners, even if they appear to be friends of Africa, to accept that Africans alone, without Western supervision can determine the use and future of their artefacts. This feeling takes the form of worrying about what will happen to looted artefacts when returned to Nigeria. Westerners are so used to considering themselves entitled to participate in deciding the disposition of African resources, including cultural artefacts, that not a single person asks the question, what right do we have to concern ourselves with what Africans will do with their artefacts and where they will house them. Some even go so far as to ask for guaranties that looted artefacts returned will not find their way back on the open market which is managed by the West.

Picton ends his article by saying that the recent withdrawal of a Queen-Mother Idia from auction because of protests has resulted in the loss of the mask to public view and concludes; “This is surely an outcome to no-one's advantage”.

What is regarded by the emeritus professor as loss needs not be accepted by all.

We should however recognize that this is a loss only to Western scholars who have access to museums and private collections where the bronzes are being held. Nigerian and African scholars have had no access to our stolen artefacts. They need to be in London or some other Western city to view the products of their forefathers and this assumes they have the financial means to pay their travel costs and other expenses, assuming they receive a visa to visit a Western city. Prof. Picton is fully aware of this and I assume he is also aware that about one fifth, if not more, of Nigerian masterpieces is in Western museum. (20)

What is viewed as a loss could also be viewed as a gain in so far as we have seen for the first time that a group of Africans have been able to stop the auction of a looted artefact. Building on this experience, other actions may be expected in future. It is clear that concerted actions by Africans, especially if supported by their governments, could change a lot of traditions with regard to dealing in looted African art objects. We have seen in the recent case that the Nigerian government also lent its support and has promised to set up a body whose sole function would be to ensure the return of the looted/stolen objects; the government would also contact the British Authorities about the issue.

One would expect Western scholars and intellectuals to support those who seek the return of their stolen/looted art objects. Arguments of retentionists sound hollow in the context of colonial oppression and robbery and contemporary scholars must abandon all colonialist ideas and assumptions if they are to make a useful contribution to the question of restitution. They should use their knowledge and influence to assist those who have been deprived of their cultural and human rights with violence and disdain. They should not be seen as supporting the oppressors or their successors in maintaining an obviously inequitable system that attributes to the West the best icons of African art.

Kwame Opoku, 6 February, 2011.

NOTES

1. http://www.theartnewspaper.com

2. Frank Willett, “Benin”, in Hans-Joachim Koloß (ed) Afrika:Kunst- und Kultur, 1999, Prestel Verlag, pp. 41-65.

3. It is interesting to see how some writers describe the Benin Pre-emptive Strike Force. Nigel Barley writes in, The Art of Benin, British Museum Press, 2010, p. 15, “An unarmed diplomatic mission went to urge the oba to comply and was attacked by chiefs acting without royal authority”. It is remarkable that the writer mentions that they were unarmed. Is a diplomatic mission supposed to be armed? There is no mention that the Oba had told this “diplomatic mission” that he could not receive them at the time proposed for the visit and that they should postpone the visit. Is this how diplomacy is conducted by entering the territory of a monarch who says he cannot receive the mission?

Paula Girshick Ben-Amos writes in, The Art of Benin, British Museum Press, 1995, p. 58:”The British viewed Benin as the main obstacle to their expansion into the agricultural interior and when in 1897, an envoy to Oba Ovonramwen was ambushed and killed, the British sent out a Punitive Expedition against the kingdom”. Here the military force of some 250 is reduced to an envoy.

Neil MacGregor, in “The whole world in our hands “makes this statement in dealing with the British invasion of Benin:

“A British delegation, travelling to Benin at a sacred season of the year when

such visits were forbidden, was killed, though not on the orders of the Oba

himself. In retaliation, the British mounted a punitive expedition against Benin. http://arts.guardian.co.uk/;

Ekpo Eyo describes the Pre-emptive Strike Force and its back ground as follows: CONSUL PHILLIP ILL - FATED EXPEDITION.

“The event that was to lead to the overthrow of the Oba began when an acting consul - General was appointed for the area in 1896. He was a young naval Officer, called Captain Phillips. With this appointment events moved rather quickly. Soon after his arrival, consul Phillips began to advise the "Benin River Chiefs" not to comply with Oba Overanwen's demand for additional tribute to the Oba of Benin for partially opening up the hinterland markets. Phillips followed up his advice to the Benin River chiefs with a letter dated November 1846 to Oba Overanwen proposing a visit to Benin city. The stated purpose of the visit was "to try and persuade the king to let white men come up to the City When ever they wanted to" (Boisrangon p. 58) Such a letter could have done nothing less than increase the fear of the Bini. The king was "to allow whitemen to come up to the City whenever they wanted to". The visit was planned for early January 1897. In reply, the Oba requested that the visit be delayed for two months, to enable him to get through the IGUE ritual during which time his body is scared and not allowed to come in contact with foreign elements. Igue ritual is the highest ritual among the Edo and is performed not only for the well- being of the king but of his entire subjects and the land. But Phillips showed no sympathy. He replied the king that he was in a hurry and could not wait because he has so much work to do elsewhere in the Protectorate. Defiantly, the expedition set out as it proposed in January, 1897 and when it arrived at UGHOTON, three royal Emmissaries met it with a request that it should tarry for two days so that they could "send up and let the King know in time for him to make his preparation for receiving us" (Boisrangon, p.84). Again Phillips regretted that he could not wait because he has so much work to do and that he would start early the next morning. And, on the next morning, he set out for Benin City. By the afternoon of that day, January 4, 1897 the inevitable happened: Seven out of nine white members of the Expedition includingPhillips himself were ambused and killed. The only white survivors were Boisragon and Locke. The story of this ill-fated Expedition is set out in Boisragon's book: The Benin Massacr” http://www.dawodu.net

See also, Richard Gott, The Looting of Benin, http://www.arm.arc.co.uk

4. Hebert Ekwe-Ekwe, What exactly does "sub-Sahara Africa" mean?

http://re-thinkingafrica.blogspot.com

5. K.Opoku, “Formal Demand for the Return of Benin Bronzes: Will Western Museums now Return some of the Looted/Stolen Benin artefacts?” http://www.modernghana.com

6. K.Opoku, “Is the Absence of a Formal demand for Restitution a Ground for Non-Restitution? http://www.modernghana.com”

7. Conclusions of Athens Conference on Restitution

http://icom.museum

8. Letter of the late Bernie Grant, Member of the British Parliament to Director of Glasgow Museum and the Reply thereto. http://www.elginism.com

9. K. Opoku,”Reflections on the Abortive Queen-Mother Idia Mask Auction”. http://www.museum-security.org

10. http://news.bbc.co.uk

BBC NEWS 24 January 2002, Nigeria demands treasures back http://news.bbc.co.uk

Guardian, UK, “British Museum sold precious bronzes Revelation adds pressure to return disputed treasures”

http://www.guardian.co.uk

The Independent,UK, “In demand: the African art pillaged by Britain” http://www.indeppendent.co.uk/news

11. Museum, Vol. XXL, no 1, 1979, Return and Restitution of cultural

Property, pp.18-21, at p.21, Nigeria

Amadou-Mahtar M'Bow Director-General of UNESCO,

“Plea for the Return of an Irreplaceable Cultural Heritage to those who

Created It”

http://www.unesco.org/culture/laws/pdf/PealforReturn_DG_1978.pdf

12. See Annex below. APPENDIX 21 http://www.publications.parliament.uk

13. http://www.elginism.com

14. K. Opoku. “Formal Demand for the Return of Benin Bronzes: Will Western Museums now Return some of the Looted/Stolen Benin artefacts?” http://www.modernghana.com

15. Nigerian Tribune, http://tribune.com.ng

16. K. Opoku, “Nefertiti in Absurdity: How often must Egyptians ask Germans for the Return of the Egyptian Queen?” www.museum-security.org

17. http://h-net.msu.edu

18. K. Opoku, “The Amazing Director of the British Museum: Gratuitous Insults as Currency of Cultural Diplomacy?” http://www.modernghana.come

19. BBC NEWS The 99% of the British Museum not on show http://news.bbc.co.uk

20. K. Opoku , “Excellence and Erudition: Ekpo Eyo's Masterpieces of Nigerian Art” http://www.museum-security.org

ANNEX

The Case of Benin

Memorandum submitted by Prince Edun Akenzua to the British Parliament

I am Edun Akenzua Enogie (Duke) of Obazuwa-Iko, brother of His Majesty, Omo, n'Oba n'Edo, Oba (King) Erediauwa of Benin, great grandson of His Majesty Omo n'Oba n'Edo, Oba Ovonramwen, in whose reign the cultural property was removed in 1897. I am also the Chairman of the Benin Centenary Committee established in 1996 to commemorate 100 years of Britain's invasion of Benin, the action which led to the removal of the cultural property.

HISTORY

“On 26 March 1892 the Deputy Commissioner and Vice-Consul, Benin District of the Oil River Protectorate, Captain H L Gallway, manoeuvred Obal Ovonramwen and his chiefs into agreeing to terms of a treaty with the British Government. That treaty, in all its implications, marked the beginning of the end of the independence of Benin not only on account of its theoretical claims, which bordered on the fictitious, but also in providing the British with the pretext, if not the legal basis, for subsequently holding the Oba accountable for his future actions.”

The text quoted above was taken from the paper presented at the Benin Centenary Lectures by Professor P. A. Igbafe of the Department of History, University of Benin on 17 February 1997.

Four years later in 1896 the British Acting Consul in the Niger-Delta, Captain James R Philip wrote a letter to the British Foreign Secretary, Lord Salisbury, requesting approval for his proposal to invade Benin and depose its King. As a post-script to the letter, Captain Philip wrote: “I would add that I have reason to hope that sufficient ivory would be found in the King's house to pay the expenses incurred in removing the King from his stool.”

These two extracts sum up succinctly the intention of the British, or, at least, of Captain Philip, to take over Benin and its natural and cultural wealth for the British.

British troops invaded Benin on 10 February1897. After a fierce battle, they captured the city, on February 18. Three days later, on 21 February precisely, they torched the city and burnt down practically every house. Pitching their tent on the Palace grounds, the soldiers gathered all the bronzes, ivory-works, carved tusks and oak chests that escaped the fire. Thus, some 3,000 pieces of cultural artwork were taken away from Benin. The bulk of it was taken from the burnt down Palace.

NUMBER OF ITEMS REMOVED

It is not possible for us to say exactly how many items were removed. They were not catalogued at inception. We are informed that the soldiers who looted the palace did the cataloguing. It is from their accounts and those of some European and American sources that we have come to know that the British carried away more than 3,000 pieces of Benin cultural property. They are now scattered in museums and galleries all over the world, especially in London, Scotland, Europe and the United States. A good number of them are in private hands.

WHAT THE WORKS MEAN TO THE PEOPLE OF BENIN

The works have been referred to as primitive art, or simply, artifacts of African origin. But Benin did not produce their works only for aesthetics or for galleries and museums. At the time Europeans were keeping their records in long-hand and in hieroglyphics, the people of Benin cast theirs in bronze, carved on ivory or wood. The Obas commissioned them when an important event took place which they wished to record. Some of them of course, were ornamental to adorn altars and places of worship. But many of them were actually reference points, the library or the archive. To illustrate this, one may cite an event which took place during the coronation of Oba Erediauwa in 1979. There was an argument as to where to place an item of the coronation paraphernalia. Fortunately a bronze-cast of a past Oba wearing the same regalia had escaped the eyes of the soldiers and so it is still with us. Reference was made to it and the matter was resolved. Taking away those items is taking away our records, or our Soul.

RELIEF SOUGHT```````````````````

In view of the fore-going, the following reliefs are sought on behalf of the Oba and people of Benin who have been impoverished, materially and psychologically, by the wanton looting of their historically and cultural property.

(i) The official record of the property removed from the Palace of Benin in 1897 be made available to the owner, the Oba of Benin.

(ii) All the cultural property belonging to the Oba of Benin illegally taken away by the British in 1897 should be returned to the rightful owner, the Oba of Benin.

(iii) As an alternative, to (ii) above, the British should pay monetary compensation, based on the current market value, to the rightful owner, the Oba of Benin.

(iv) Britain, being the principal looters of the Benin Palace, should take full responsibility for retrieving the cultural property or the monetary compensation from all those to whom the British sold them.

March 2000

http://www.publications.parliament.uk

ANNEX II

Nigeria demands treasures back

(Thursday, 24 January, 2002, 08:08 GMT http://news.bbc.co.uk)

Many works were acquired when Britain was an imperial power

The Nigerian parliament has called for the return of Nigerian works of art in the British Museum.

The country's lower house of parliament has called on its president, Olusegun Obasanjo, to request the repatriation of the artifacts, taken away during British colonial rule in the 19th Century. British forces seized a remarkable collection of sculptures from the city of Benin, including the so-called Benin Bronzes, now a highlight of the British Museum's collection in London.

Other Nigerian artefacts have found their way to European museums through the connivance of corrupt officials, who helped collectors smuggle them out of the country.

Unanimous

Wednesday's motion urged the government to safeguard Nigerian museums from being "burgled" by hired agents.

It also ordered the Nigerian National Commission for Museums and Monuments to provide a list of all Nigerian artefacts at the British Museum - and list their value.

The motion, sponsored by 57 legislators, was passed unanimously.

Time magazine reported Omotoso Eluyemi, head of Nigeria's National Commission for Museums and Monuments, as saying: "These objects of art are the relics of our history - why must we lose them to Europe?"

"If you go to the British Museum, half the things there are from Africa. It should be called the Museum of Africa."

Recently, British Museum director Robert Anderson refused renewed calls for the "Elgin marbles" from the Parthenon to be returned to Greece.

Writing in The Times, Mr Anderson called the Parthenon sculptures "one of the greatest treasures of the British Museum".

Members of the British Punitive Expedition of 1897 against Benin with looted Benin ivories and bronze objects

Members of the British Punitive Expedition of 1897 against Benin with looted Benin ivories and bronze objects

Alter group honouring Oba Akenzua I, Benin, Nigeria, now in the Ethnology Museum, Berlin, Germany. This piece is not in the reserve collection of the museum.

Alter group honouring Oba Akenzua I, Benin, Nigeria, now in the Ethnology Museum, Berlin, Germany. This piece is not in the reserve collection of the museum.

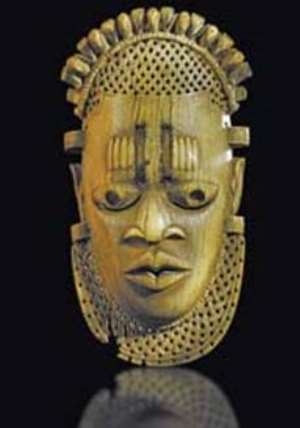

Commemorative head of an Oba, Benin, Nigeria, now in Ethnology Museum, Vienna, Austria. This head is not in the reserve collection of the museum

Commemorative head of an Oba, Benin, Nigeria, now in Ethnology Museum, Vienna, Austria. This head is not in the reserve collection of the museum

We’ll no longer tolerate your empty, unwarranted attacks – TUC blasts Prof Adei

We’ll no longer tolerate your empty, unwarranted attacks – TUC blasts Prof Adei

Bawumia donates GHc200,000 to support Madina fire victims

Bawumia donates GHc200,000 to support Madina fire victims

IMF to disburse US$360million third tranche to Ghana without creditors MoU

IMF to disburse US$360million third tranche to Ghana without creditors MoU

Truck owner share insights into train collision incident

Truck owner share insights into train collision incident

Paramount chief of Bassare Traditional Area passes on

Paramount chief of Bassare Traditional Area passes on

Two teachers in court over alleged illegal possession of BECE papers

Two teachers in court over alleged illegal possession of BECE papers

Sunyani: Victim allegedly shot by traditional warriors appeals for justice

Sunyani: Victim allegedly shot by traditional warriors appeals for justice

Mahama vows to scrap teacher licensure exams, review Free SHS policy

Mahama vows to scrap teacher licensure exams, review Free SHS policy

Government will replace burnt Madina shops with a new three-story, 120-store fac...

Government will replace burnt Madina shops with a new three-story, 120-store fac...