Preamble: The Unhealthy Political Climate in Ghana

Ghana's airwaves is inundated with so much rumour mongering, unguarded political statements and empty promises, and the media have an acute flair for hyping trivial, mostly parochial political, matters to the detriment of salient national issues that ought to be at the forefront of public discourse. Consequently, this rather unprofessional, perhaps indiscreet and skewed, media landscape inevitably compels the discerning citizen, the serious-minded Ghanaian, to often gloss over many of the stories and headlines that feature in the local media, particularly those emanating from politically-aligned press and radio stations.

The problem is even compounded by a sad reality, that of petty partisan politicking of public discourse which is causing many well-meaning, informed and objective Ghanaians to keep an arm's length from discussions on pertinent national issues, let alone take an active role in politics, in order to avoid being blackmailed or labeled 'enemies' or 'sympathizers' by those on either side of the political divide, a situation that has recently caught the attention of senior statesmen, including former supreme court judge Justice Carbie and industrialist Appiah Menka.

Yet there are instances when what was thought to be one of those 'empty' political promises and thus given a lighthearted treatment suddenly appears to be an unfolding reality, when what seemed remote begins to assume a practical manifestation. And it is at this juncture that one must make their known or heard their concerns before what could be a potentially bad (though well-intentioned) decision gets executed, when one must hastily act in their technical capacity and invoke their sense of nationalism to prevent, or to put in a more civic way, impress upon their leaders who have been entrusted with the management of societal resources to, if possible, rescind or review a major decision with massive implications that are irreversible in the long-term before it is too late, regardless of the consequences or reaction that might be given to it.

Such is the case concerning the story of the construction of a new international airport, besides Kotoka, in Accra, a story which has for some time been paraded in the Ghanaian media. It reads like this: 'Government to build a new Airport at Prampram'; the purpose: 'to address the capacity constraints and future anticipated growth at Kotoka International Airport'. And, like any other policy statement or word of promise originating from the lips of Ghanaian (and by extension African) politicians, one has every good reason to treat such pronouncements with the usual pinch of salt it deserves; after all, similar promises made in the past have only fallen on the grass.

Consider, for a moment, the litany of pledges made by the NPP and the NDC, the two main political parties in Ghana, on myriad campaign platforms which evaporate into thin air, once they are sworn into office. The list is too infinite to be able to accommodate in a small piece of writing such as this, but mention can be made of just one example of the numerous unfulfilled promises made to Ghanaians by our politicians, to underscore the point being made here. It is an example that directly speaks to the widespread public concerns about the size of government the nation can sustain on our fast-drying national coffers, particularly in the face of dire economic conditions, and at a time when most countries the world over are seriously trimming the size of their government and public sector, and introducing measures to tighten their fiscal spending whilst ensuring greater accountability in the use of tax payer monies, in the wake of the recent economic crisis.

In 2000, the NPP promised in its manifesto to slash the size of government if it came to power, accusing the then ruling NDC government of being insensitive to the plights of the suffering Ghanaian masses. However, it ended up having one of the largest, if not the largest, governments in Ghana's political history, during its eight-year rule. Condemning the move on the same grounds, the then opposition NDC party promised in their 2008 manifesto to create a leaner government in Ghana, if given the nod to rule, but today it has the largest ministerial portfolios with no precedent (and we're still counting). This situation has led some people, myself included, to conclude that rhetoric is the trademark of most African politicians while inaction or capriciousness constitute their principal deficiency.

However, this conception seems to be have been challenged (and I must qualify it again 'seems to have been challenged') this time by the apparent haste with which the current government's plan of constructing a new international airport in Accra is being pushed through. My sensibilities were actually awoken to the reality of the issue just a couple of days ago, when Joy News reported the visit by Ghana's transportation minister, Dzifa Ativor, to the proposed site of the multi-billion dollar airport project, in the Ningo-Pampram District of the Greater Accra Region. Her mission, as reported in the story, was unambiguous: to inspect the project site and to assure, in her own words, 'the whole world that the new airport is going to be started soon'.

Happily, minister Dzifa, by refusing to give a timeline interpretation to her 'soon' phrase, carefully avoided the trap most African leaders all too often fall into by providing unrealistic 'action' dates for the realization of their promises just to excite their hearers, only to resort to giving new dates once the initial ones have expired without any action. Clearly, the minister's approach marks a departure from the norm, for which she must be commended. Perhaps, if a similar attitude is adopted by other Ghanaian and African politicians, it would help salvage the sunken image of African politics, although, yet again, this assertion in conjectured on the belief that the minister would stay true to her words.

But the direct concern or major preoccupation of this article isn't to chastise the Ghanaian media for its lackadaisical performance (as matter of fact, few of them are actually doing a good work); nor is it intended to mock the flip-flop attitude of Ghanaian politicians (I acknowledge there are some fine gentlemen and ladies in both the NPP and the NDC, including other party-less public officials in Ghana who have or are contributing their best to uplift the image of our dear nation). Rather, its specific goal is to examine the suitability of the present government's proposal to construct a second international airport in Accra, and to explain why I think this is not the best decision for the country.

In doing this, I provide a backdrop to the project, including the rationale given for it as well as its official handling so far, and then question the basis of determining the need for a new international airport in addition to the already proposed ones. Next, I pinpoint the major weakness characterising the geographic distribution or spread of development in Ghana, and argue why locating a new airport in Accra would serve to deepen, rather than close, the existing regional imbalance in development. I then proceed to enumerate the reasons why building an additional airport in Accra, potentially the nation's largest, will aggravate the ills facing the city of Accra in particular and the larger rural-urban drift in Ghana, which has incidentally become an issue of concern to our sitting president. I conclude by offering some alternative plans for realizing the goals that the development of the new airport is intended to accomplish.

Backdrop to the New Airport Project: A Project shrouded in Secrecy?

Few, perhaps with the exception of government insiders, knew about the government's intention to construct a new airport in Accra until Alhaji Collins Dauda, the then minister of transportation, disclosed it during a visit to the families of those whose lives were lost in the regrettable June 2, 2012 aviation disaster at the Kotoka international airport (KIA) involving a 727 Boeing Allied Air cargo plane flying from Lagos to Accra, which claimed the lives of ten people.

At the time of the disclosure, the minister pointed out that the decision to build a new international airport had not been occasioned by the unfortunate incident, but that it was a plan that had been on the drawing board for some time. Instead, the justification given by him for the project was because of existing capacity constraints at KIA, the nation's only international airport, due to increased fleet. Alhaji Dauda further revealed that the (potential) site of the project had been found, specifically at Prampram, in the Dangme West District (now Ningo-Prampram District) of the Greater Accra Region, and that a group of surveyors from the Surveyors Department were already on site conducting initial site analysis.

Barely three months on, at a press briefing, the same minister hinted that an MOU had been signed between the government of Ghana and China Airports Construction Cooperation (CACC), China's state-owned civil airports development company, in October 2012, to undertake feasibility studies for conceptual design of the project and also added that negotiations were underway for the acquisition of 16,000 acres of land needed for the project. Then, fast-forwarding to February 2013, it was published that CACC was set to begin construction of the new airport, suggesting that a contract had been signed to that effect, with one particular source indicating that the requisite funding arrangements had been finalized, awaiting 'official' approval of the site.

However, during the recent (April 30, 2013) visit to the site by the new transportation minister, Mrs. Dzifa Ativor, who apparently assumed the role of her former boss following President Mahama's inauguration into office, she empathically stated that, or was rather quoted as saying that, 'the government would soon invite the public to bid for a feasibility study of the project', contradicting the earlier statements and reports made by her predecessor or attributed to other government officials, suggesting: (1) that the contract for feasibility studies on the conceptual design of the project had already been awarded to CACC, and (2) that the contract for the actual project had been awarded to CACC, pending official approval.

If any of these is true, and unless land and design feasibility studies are completely distinct tasks (as the two seems to reinforce each other in my view), then it raises important questions about the manner in which the project is being handled by government. For example, if is it true that contract for the feasibility study for the project's conceptual design has indeed been awarded to the Chinese company, was the decision reached after a competitive tendering process in which 'the Ghanaian public' was invited to bid? Next, if the contract for the actual project has also been awarded already, as is being speculated in the media, even before the feasibility studies is yet to be undertaken, then Ghanaians have reason to know what the actual status of the project is. What's more, we need to know what role CACC is purported to be playing in the project?

So, as we can see, there are already some critical questions that remain unanswered about the project at hand, even in its initial stages. The intention here isn't to accuse any government official of corruption, but to emphasize the need to give adequate attention to one important virtue that is often lacking in African political governance: transparency. In the country where I'm currently residing (i.e., Canada) projects of this size, scale and scope cannot progress to the phase Ghana's new airport has reached without being subjected to rigorous public scrutiny as well as numerous consultations with a wide range of stakeholders, plus a series of independent evaluations.

But here again this does not constitute my primary goal for writing about this project. Instead, it is to seek for satisfactory explanations, first, regarding why Ghana needs yet another international airport besides those that have already been earmarked for upgrade to international standards, and, second, what informed the choice of Accra, by government, for this latest project. It is in approaching these two key concerns that I now proceed to describe what I consider to be Ghana's major development challenge, before dealing with the substantive issues at hand.

The Problem of Asymmetric Spatial Development in Ghana

Spatial asymmetry, otherwise known as uneven or imbalanced development, has characterized Ghana's development since independence. This imbalance, which geographically manifests itself in the acute infrastructural gaps, social and economic opportunities between Ghana's northern and southern regions, is largely the product of colonial planning system.

Colonial planning concentrated 'development' (including roads, railways, schools, hospitals, seaport, etc.), as well as political power (including the seat of government, parliament, civil service and judiciary) in the southern region of Ghana, in order to further the colonialists' economic aim of developing trade routes and easy, low-cost access to, and for moving, resources from the Gold Coast to their respective metropoles. Moreover, the safety and breeze afforded by southern Ghana's proximity to the Atlantic Ocean, as well as its relatively uninhabited and less rugged terrain compared to the interior, naturally made it conducive for European settlement.

But underneath this pattern was another reality: the resource and ecological variation between southern Ghana, which is mineral-rich, forested, arable and well-populated in comparison to northern Ghana's mineral-poor, arid and sparsely-populated zone. This resource variation and inequality has continued to reinforce the north-south development gap and accounts for the mass migration of northerners to southern Ghana, despite attempts by successive governments since independence to reverse the trend.

Perhaps among all the seven or so post-independence regimes Ghana has had, Kwame Nkrumah's socialist government is the one to have seriously and consciously attempted to spread development more evenly within the country by, for example, setting up several state-owned enterprises (SOEs), training colleges, military and police academies, among other socio-economic facilities, in various parts of the country, including the north. But the location of strategic assets and key industries, including the Akosombo Dam, Valco, the new Tema and the expanded Takoradi habours, as well as the headquarters of several national institutions, including the SOEs, and related housing infrastructure down south, particularly in the so-called 'golden triangle'(defined as the zone between Accra-Tema, Kumasi, and Sekondi-Takoradi, which are, respectively, the first, second and fourth largest urban centres in Ghana and is estimated to accommodate over 80 percent of Ghana's industrial activity, non-farm employment, tertiary institutions, both public and private), for reasons cited above, overpowered or diminished the effects that the other activities were intended to have, in terms of stemming the tide of people migrating southward because of the better opportunities that existed there.

This same reason, plus those proffered above, account for the failure of subsequent governments after Nkrumah to bridge the north-south development divide, and, by extension, the larger rural-urban population drift. Off course, this is not to discount the efforts and achievements made by the various post-Nkrumah governments on this front, including: the Bussia government's (1969-72) Rural Electrification Project (REP); the Rural Enterprise Project (REP) of the PNDC government (1992-2000); the NPP government's (2000-2008) Northern Development Fund (NDF); and the NDC government's (2008-) Savannah Development Authority (SADA), an upgrade of the NDF. These also include several other unmentioned initiatives, programs and projects all designed to reduce the chasm between Northern Ghana, technically defined to encapsulate the Northern, Upper East and Upper West regions of Ghana, and southern Ghana, comprising the remaining seven regions.

But despite the contributions of these interventions, plus those of countless donor-funded programs, including the proliferation of NGO activities and social services provided in the north, it is undoubtedly clear that the development gap between the two major enthno-geographic zones in Ghana has actually widened rather than bridged over the years, a situation confirmable by the disparities in myriad welfare indicators, such as real incomes, employment, food security, standards of education, and access to health and sanitation.

While it is true that natural constraints and historical precedent may be the overarching causes of the development asymmetry between northern and southern Ghana, we cannot certainly underestimate the import of other factors, namely: simmering ethnic conflicts in the north, cultural factors, weak (or lack of) coordination of development efforts, lack of strong political will (or politics in general) and, in recent times, climate change. This is indicative of the multi-dimensional and complex disposition of the challenge, suggesting, by implication, that a well-packaged, holistic and tactical approach, that represents a break from the past, is what is required in tackling what could be described as the major hurdle facing independent Ghana's development comprehensiveness.

So what has the construction of the proposed new airport got to do with the age-old, north-south divide in our backyard? One may ask. Well, the answer is straightforward here, even though a fuller appreciation of this will emerge from the discussion on the implications of siting another international airport in Accra later on. And the answer is this: large-scale, strategic projects such as airports, which have huge spillover economic effects, have a bigger potential in leveraging or (re)balancing development more evenly across a country than relatively small or piecemeal programmatic actions.

In other words, constructing the new airport, even if warranted, in say Bolgatanga will do more to close the north-south divide than the cumulative impact of many of the tiny projects currently being undertaken under the auspices of poverty reduction in northern Ghana. But even proceeding with this plan in itself raises another question, equally germane: if the government of Ghana can afford to build another airport (whether by cash payment upfront, or loan agreement, or some private-public partnership, or whatever arrangements are going to be used to finance the project, which we're yet to know), why not spend part of that money to augment KIA's capacity and or upgrade the Kumasi and Tamale airports to international status and use the remainder to fund other critical development needs? This ultimately leads to my next question and concern: is it worthwhile for a developing country like Ghana to have five international airports?

Does a small developing nation such as Ghana need five international Airports?

This question may sound absurd at first to readers, but the stack reality is that going ahead to build a new international airport in Accra (or any part of Ghana for that matter) will bring to five the total number of international airports officially announced by government. Kotoka, as we all know, has been the country's only international airport serving as Ghana's gateway to and from the rest of the world since its construction in 1966. The remaining five regional airports, namely, Tamale, Kumasi, Sunyani, Takoradi and Bolgatanga are, by their name and capacity, domestic in service and scope.

Purported capacity constraints, ageing infrastructure and presumably the discomfort of long distance travel by international travelers to and from the north, and a later pre-condition for Ghana's hosting of CAN 2008, led to government's decision to upgrade the Tamale airport to international standards in the run up to the tournament, although the project is far from complete. Then, roughly a year ago, President Mahama, then vice president, announced at a visit to Takoradi that government was in the process of securing land for the construction of a new airport in the oil city. Logically, this was in response to the influx of investors, expats and tourists to the city following the discovery of oil and gas sometime in 2007.

Meanwhile, talk of elevating the Kumasi airport to an international status had been on-going for a long time, and the airport had been undergoing some facelift under the erstwhile NPP government until few weeks ago when work 'officially' commenced to modernize and expand it. While all these plans or projects are in session, then out of the blue comes the news of constructing yet another international airport in Prampram, near Accra metropolis! So what is the problem with having five international airports to serve the travelling needs of Ghanaians and international visitors, at a time when the country's economic prospects are brighter than before, and in particular when middle class Ghanaians are taking to the skies?

First of all, noble as this idea may seem, it must be premised on some evidential basis, and not just some political reasons. In general, we can roughly determine the international aviation needs of any nation on the basis of the following factors: land size, population size and distribution, demand for international travel, and economy. This means that large countries will generally have need for more international airports than smaller ones. In a similar vein, nations with larger and sparsely or evenly-distributed population will, all things being equal, have a need for more international airports than those with smaller and or concentrated population patterns, as will economically stronger nations will be able to afford more international airports than poorer ones.

The number and frequency of travelers to and from a country will also greatly affect its aviation needs, regardless of physical size, population and strength of economy, such that for, example, a country like Kenya with a highly international mobile population (comparable to that of Ghana) as well as huge influx of tourists and diplomats (thus, by implication, performing a global function as it hosts the regional head office of several United Nations and international donor organizations in Africa) will have need for more international airports than Ghana, even though both countries are roughly similar with respect to size of population, land and economy.

Looking at the above factors, we can deduce that no single factor can by itself constitute the sole determinant of the number of airports a country can own. Furthermore, it is likely that these major determinants will be mediated by other secondary factors such as the efficiency of non-air transportation systems in place and domestic aviation policy. For instance, where other modes of travel (road, rail and water) are in good shape, the need for an additional airport due to growing demand may be curtailed through the development of transnational rail and highways to facilitate land-based travel, as for example, exist between Canada and the USA. Likewise, if a country's domestic policy is to encourage the growth of its internal airlines market, it might choose to expand the capacity of its existing (stock of) international airports to provide a bigger market for domestic carriers rather than build additional international airports.

Turning to Ghana, the answer to this question will obviously rest on some hard facts which I'm not privy to (such as the current, expected and future capacity of post-renovation KIA vis-à-vis expected increase in landing fleet) as well as on others plain to the ordinary Ghanaian. However, my candid opinion is that Ghana does not need a fifth international airport, at this material time, for the following five reasons:

1. Economically, Ghana is grappling to meet the most basic needs of its populace. These needs include, but are not limited to: adequate water and sanitation, housing, affordable and reliable energy, food security, good roads and accessible health care. Having five international airports, while appearing glamorous, seems rather superfluous when Ghanaians are queuing for water, when they are struggling to pay their electricity bills, when power is erratic, and when there are still many schools (hundreds of them) under trees. In a nutshell, it would be, using the famous Ghanaian political expression for disapproving 'fanciful' projects, 'insensitive to the plights of the suffering Ghanaian masses'.

2. Although the upgrading work on Accra, Kumasi and Tamale airports are on-going, it does not appear that all the funding is secured to ensure the timely completion of these projects. Meanwhile, nothing has been heard from the government regarding the state and progress made on its plans for executing the Takarodi project, since its initial revelation.

3. As it is likely that a significant part of the funding for these projects, particularly the latest add-on, will be borne by the public purse, whether by loan or through some other means, chances of spiking our national debt is high.

4. The four other international airports, when operational, should be able to relieve KIA of much of the anticipated increase in air traffic.

5. Some projects can turn into 'white elephants' due to overestimation of demand for and revenue from them, such that it might take a longer than expected time to recoup the investments sunk into them, as I foresee with the new Accra airport, resulting in what the renowned planning academic Peter Hall calls 'planning failure'.

Now I turn to the consequences of locating a new international airport in Accra, even if reasonably justified.

The Urban Impact of Building a New Airport in Accra

Accra, A city faced with extraordinary Challenges

Ghana's capital and certainly most important city, politically, financially, educationally, culturally and spatially, the city of Accra has, within a matter of decades, transitioned from a small colonial administrative district into an expansive metropolis struggling to cope with, or rise up to, the challenges of rapid urbanization, unfortunately ridden on the back of a weak urban economy.

With a 1984 population of just under 1 million people, Accra now struggles to accommodate over 3 million urbanites, hemmed within a landmass of 200sq km, about a third of whom live in squalor conditions. Weak planning regimes, inefficient land use regulation and underinvestment in infrastructure, coupled with rapid growth, has, however, meant that 'functional' Accra is now underbounded, having overshot its boundaries and in the process amalgamated with adjoining municipalities in all directions: Ledekuku-Krowor and Tema metropolis to the east; La-Nkwantanan-Madina, Adenta and Ashiaman to the north-east; Ga East to the north; Ga West to the north-west; and Ga Central and Ga South to the west, reaching as far as Kasoa in the Central region.

A largely informal economy, inequality of opportunities and years of neglect of poorer neighbourhoods have given Accra a dual identify, having on one side enclaves of relatively well-planned, low density, amenity-sufficient upper and middle income neighbourhoods, such as East Legon, Ridge and Cantonments, starkly contrasted with swathes of densely-populated, amenity-deficient, rundown, inner-city neighbourhoods, such as Chocker, Jamestown and Nima. Poor and insufficient service delivery, narrow and poorly-connected roads and centralization of functions, amidst a generally unresponsive and resource-starved city government and a largely care-free, environmentally less conscious populace, has left Accra saddled with problems of uncollected waste, chocked drains, disjointed land uses, lack of green spaces, standing traffic, and perennial flooding. Efforts at tackling these challenges have largely been ineffective, mainly due to their ad hoc nature, inability to deal with the underlying root causes, and institutional weakness.

The above is, in a nutshell, a descriptive situational analysis of Accra. Thus, the salient question for us to answer here is in what ways and to what extent will the construction of the new airport in Prampram add to or alleviate some of the afore-mentioned challenges facing Ghana's capital? In answering this, I have decided to look at the major impacts of new airport construction from four categories: economic impacts; physical/morphological impacts; environmental impacts; and social/health impacts.

Economic Effects

There is little doubt that such a massive multi-billion dollar infrastructure project which, if we're to go by the description being given to it by government, is poised to become Ghana's largest airport, will generate widespread economic benefits for the immediate locality of Prampram, the region of Accra and the nation as a whole. Because an airport is a multi-sectoral and multi-occupational industry, having several direct and indirect effects, as well as numerous forward and backward linkages to a host of industries that include airline companies, travel and tour agencies, engineering services, restaurants, real estate, insurance companies, banks, security services, administration and myriad other ancillary services (e.g., hotels, transportation), it can be expected that the project will serve as a major boost to the local, regional and national economy, with gains from jobs, incomes, taxes and GDP contributionright from its construction to its operationalization.

However, the exact amount of economic benefits that will accrue to the nation will depend, for example, on how many Ghanaians get to be hired in the different phases of the project and how much of the money that flow into and from the project stays in the local and national economy. Often times, many projects that are estimated or anticipated to provide lots of benefits end up falling below expectations, because foreign companies and personnel end up taking the most lucrative aspects of the project, especially where foreign government grants and loans are involved, as will likely be the case with the project in question. Besides, the low point of this economic impact is that it will increase regional inequalities in development, further strengthening the north-south divide, as stated elsewhere.

Physical/Morphological Impacts

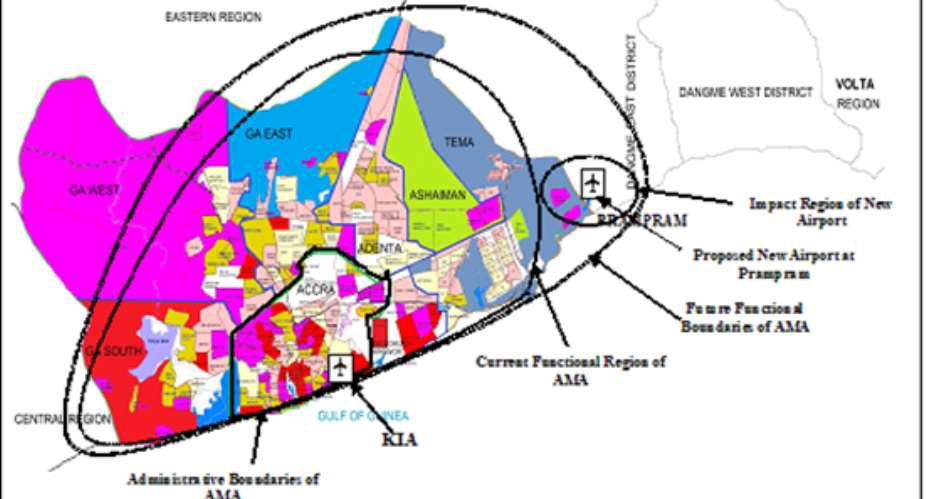

The spatial impacts of the proposed new airport in Accra can be looked at from three main perspectives or areas: urban form, mobility and functional cohesion. In terms of impact on urban form, the new airport will, as a bundled activity area or new growth pole, constitute another centre that will help diffuse and deflect some activities and population movement away from existing centres in Accra, especially the central business district, making the Accra city-region more polycentric in nature. However, the idea of spreading population away from Accra will only be achieved in the short-term. This is because in the long run, it will rather contribute to Accra population's growth as new activities will fill up any voids created as a result of the relocation of certain functions from Kotoka. What's more, the new airport will encourage sprawl as new development spring up around it in leapfrog patterns that will eventually fuse Ningo-Prampram District with the functional boundaries of AMA, further stretching the frontiers of the city into a contiguous urban agglomeration that will approach the scale of a mega city region such as Lagos. When this happens (as shown in the figure below), the traffic situation in and around Accra will deteriorate, presenting its own set of environmental and health implications, along with other urban management challenges. These challenges include spatial fragmentation, which will portend a lack of cohesive development.

In a nutshell, these developments will compound the problems of urban management in Accra. This is because management of mega urban regions, which Accra already is, presents huge problems due to the fragmentation of governance and decision-making machineries, as each urban administration concentrates its functions, including planning, transportation and waste management within its political boundaries, thereby limiting the scope for collaborative approaches to dealing with problems that are supra-urban in nature.

Figure 1: Map of Accra Metropolis Showing the Growth Impact of the Proposed New Airport at Prampram

Figure 1: Map of Accra Metropolis Showing the Growth Impact of the Proposed New Airport at Prampram

Environmental Impacts

The environmental consequences of the new airport project include disturbance to existing wildlife habitats as well as other ecological impacts from land use conversion and land cover change, including interference in ground water cycle, natural water purification processes, urban 'heat island' effects and potential flooding. While in principle all the above effects will not be specific to the Prampram project site (that is to say, they will occur anywhere the airport will be located), we can fairly assume that these ecological impacts will be higher in Prampram which is greener than at any alternative location in the north, which is dryer. The other critical environmental impact, more germane to Accra, is greenhouse gas emissions from vehicular congestion and long commute and its effects on air quality and micro-climate, as well as noise pollution, which leads me to the social and health impacts.

Social and Health Implications

The construction of the new airport close to Accra will constitute yet another incentive that will open the flood gates for a wave of immigrants from all over Ghana, particularly the poor regions of the north, to settle in and around Prampram, with all of its related consequences: crime, prostitution, hawking, sub-standard housing, environmental degradation, disease spread, etc. It will also include the loss of productive man-hours due to long commute and traffic congestion. These outcomes will mock or fly in the face of efforts and persistent campaigns by government to arrest or control the rapid rate of urbanization in Ghana, an issue that has become of personal concern to President Mahama, who, recently launching the first national urban policy with the singular aim of curtailing the unsustainable growth of Ghanaian cities, painted a grim future of life in our cities, if the current rate or urbanization goes unchecked. Incidentally, the president repeated the same warning in a keynote address he delivered at the third Times CEO Africa Summit in London on April 30, 2013, the same day his transportation minister undertook her visit to the project site. Given the fact that Ghana has now transitioned from a rural to an urban society, having crossed the 50 percent threshold, a sense of urgency is needed in approaching this issue.

Alternatives Worth Considering

Having enumerated the full set of reasons why I oppose the construction of a new international airport in Ghana and Accra for that matter, I now offer some suggestions that could be considered by government as an alternative to building a new airport in Accra. But before I did that, however, it is necessary to revisit the main justifications given for the project. According to the two official mouthpieces of government as far as the new airport project is concerned, that is, the former and current minster of transportation, there are three very explicit reasons why the new airport is needed, all of which border on problems at Kotoka, the nation's only international airport. These are:

1. Inadequate parking space for aircrafts

2. Congestion at arrival/departure halls or terminals

3. Expected increase in flight volume, resulting from economic growth, FDIs, and tourism.

Off course, the other reasons given by the ministers, such as job creation, cannot be considered as one of the primary reasons for embarking on the project but as benefit that will inure to society for having it. Nevertheless, we can still include it in the list of the project rationales since, after all, an airport is not end in itself but as a means for achieving other economic goals.

The five recommendations I now make below, although largely a rehash of the key points already made above, have been reframed to provide a more convincing argument for government to reconsider the idea of going ahead with the project. They are:

i. Expansion and Upgrading of KIA

It has been indicated on several platforms that the Kotoka international airport is undergoing major upgrades to improve its capacity and enhance traveler experience. It is true that large chunks of the land around the facility has been encroached upon, which means that it will take some time and legal battles if government should decide to reclaim those lands for expanding the airport. That notwithstanding, it should be possible to redesign and utilize the existing space innovatively to absorb some additional increase in air traffic. Several examples of this can be found around the globe, including London's Heathrow airport.

ii. Development of the Takoradi Airport

Constructing a new international airport at Takoradi makes perfect sense to me because the city is expected to become the hub of the new oil industry in Ghana, if it already hasn't. And given that a significant portion of foreign capital and labour coming into Ghana and specifically the oil sector will end up in (or around) the city, plus government's own plans to develop a gas plant close to the city, amid other initiatives to revamp the region's industrial sector, it is absolutely justifiable for Takoradi to have a modern, international airport that will cater to the travel needs of locals and foreigners who will be living, visiting or working in the city. Therefore, rather than rush to construct the new airport at Prampram, it seems more reasonable for government to devote the needed attention and resources to the implementation of the Takoradi project, which appears to have faded away from the public arena since President Mahama announced it last year.

iii. Upgrading of Kumasi and Tamale Airports

Perhaps the Kumasi and Tamale projects are long overdue. This is because, as Ghana's second largest city, with a rich cultural heritage and a significant share of Ghanaians living in the diaspora, retrofitting the Kumasi airport in order to provide direct connection to major international cities such as London, Amsterdam, New York and Frankfurt will undoubtedly be a viable project. Similarly, elevating the Tamale airport to international status will ease the strain that Hajj pilgrims from the north have to endure each year in embarking upon their pilgrimage to Saudi Arabia.

All these three projects, if completed, will cut substantially the existing and expected growth in air traffic at the Kotoka international airport. But there is another compelling reason to implement the above projects: the new international airports will induce the various embassies in the country, particularly those which receive huge visa applicationsnamely, the United States, UK, Germany, Holland, France, Italy, Canada and Australiato open up visa sections in Kumasi, Tamale and Takoradi. This will have a huge impact not only in terms of reducing the tussle Ghanaians from every nook and cranny continue to undergo in their quest to secure visas for travelling to these countries, but also lessen the wider socio-economic problems and risks associated with it, including traffic, accident, travel cost, etc. However, having a new airport in Accra will not achieve this feat, as there will be no incentive for consulates in Accra to decentralize their services.

iv. Investing in Water, Energy, Waste Management and Transportation

Putting in more money to improve upon water supply, energy, waste management and transportation in Ghana and keeping our cities clean and efficient will cumulatively improve the welfare of Ghanaians and increase our national competitiveness, far more than the combined effect of having five international airports, which appear rather too ambitious for a lower middle income nation, such as ours, confronted with a litany of challenges to have, even though I support all the other airport projects with the exception of the Accra project. In terms of water, not only must we ensure efficient delivery system, but also harvest rain water and recycle waste water. Regarding energy, we must reduce our reliance on just one or two energy sources, particularly hydroelectric power, and diverse our energy sources to incorporate renewable energy forms such as wind and solar power, especially given our tropical climate. Rather than landfilling waste, we must take active steps to recycle waste, particularly organic waste for compost, and also think about waste-to-energy systems. For transportation, of which air transport is only a fraction, it is high time we invested in cheaper and smarter modes of travel, such as intra and intercity rail, which are also safer and more sustainable than road transport, the predominant mode of travel in Ghana, which continues to take a huge toll on lives in our country. All these proposals point to one thing: the prioritization and application of technology to address the urban challenges facing the 21st century African metropolis.

v. Reforming Urban Governance

This may be considered an off-point to the issue under discussion here, but until we reform the administration and planning of our cities and towns, to tackle the underlying causes of congestion, uncontrolled sprawl, erosion of public open spaces, filth, pollution, environmental degradation and incompatible land uses, and find smarter solutions to waste, traffic and growth management, continued urbanization risks stifling economic growth, as the president has warned. But the solution to these problems must start from the very heart of the problem: the institutions charged with the management of our cities. To a large extent, the state of our cities is a reflection of the quality and competence of our city authorities. I cannot use the limited space here to enlist and provide solutions to all the inefficiencies of, as well as deficiencies inherent in, our current local government system, but in a situation where waste collection is abysmal, where illegal structures continue to pop-up everywhere in Accra in flagrant violation of existing planning laws, where city administrators are unresponsive to the needs of its citizenry, and where virtually all internally generated funds are expended on meetings or deliberations rather than action as happened with the Accra Metropolitan Assembly last year, then it is clear that we have a huge problem in Africa!

Conclusion

I have, in this article, critically reviewed the present government's decision to build a second international airport in Accra, Ghana's capital, because of what it says are major capacity constraints at KIA, now and expected. Having analyzed the economic, social and environmental impacts of building another international airport in Accra, vis-à-vis the regional disparities in development mirrored by sharp north-south divide, I argue that going ahead with the project will heighten regional inequalities in development, accelerate rural-urban migration, encourage sprawl, increase congestion and traffic in Accra, impact on air pollution and constitute to climate change, further enlarge functional borders of Accra, and strengthen the primacy that Accra city-region is already enjoying over other Ghanaian cities. In exploring the full range of options available to government other than putting up a new airport, including initiatives announced by government itself, such as the on-going project to elevate the Kumasi and Tamale airports to international standards and the plan to build a new international airport in Takoradi while upgrading the other regional airports, I have provided reasons why these alternative projects are more than sufficient to ward-off the existing and future problems at KIA. In addition, I have underscored the need for government to boost urban water and energy supply, invest in rail infrastructure and waste-to-energy systems, and reform the structure of urban governance institutions to ensure greater efficiency and reliability in service delivery, accountability, better growth management policies, and enforcement of planning legislations and bylaws. It is only by addressing these issues, with a sense of urgency, that we can reap the full benefits of, or give true meaning to, development and urbanization and avoid the state of inertia Africa appears to have hibernated itself into, shortly after a promising post-independence impetus, while other nations, some of which trailed behind us a few decades ago, continue to leap forward.

By: Komiete Tetteh

The author is a city planner from Ghana residing in Canada. He can be contacted at [email protected]

Notes and References

In a speech delivered at the 8th 'Re-Akoto and Seven Others Memorial Lecture' to mark the 2012 Law Week of the Ghana School of Law, senior statesman and industrialist Mr Appiah Menka enlisted what he called 'the three explosive evils' destroying the Ghanaian society, namely, partisan politics, corruption and tribalism. He warned that unless these triplet behemoths are uprooted from the Ghanaian society, the nation would suffer the same fate that befell the 'animal farm', and called for urgent steps to address these. This sentiment was also expressed by former Supreme Court judge, Justice Carbie, who accused the two dominant parties in Ghana, NPP and NDC, of reducing national problems to 'mere propaganda', thereby polarizing the Ghanaian society and whipping up political tension in the country. He, like Mr. Menka, called for efforts to curb the situation. These observations by two of our most respected senior citizens underscore my assertions about the media and the current political landscape prevailing in Ghana now.

'Ghana to Build a New Airport at Prampram' (2012, August 5). Daily Graphic. Retrieved from http://edition.myjoyonline.com/pages/tourism/201206/87794.php

This promise is referred to in the NDC's criticism of the performance of the NPP government's 2000-08 rule, in which they highlighted the failure of the past government to honour their 2000 campaign promise of cutting down the size of government. This criticism was contained in a statement captioned 'Why Ghana shouldn't trust Akuffo-Addo and NPP' released on August 1, 2008. It was published on MYJOYONLINE and can be accessed from http://politics.myjoyonline.com/pages/news/200810/21171.php

See page 8 of the 2008 NDC Manifesto titled 'Manifesto for a Better Ghana. Investing in People, Jobs and the Economy' . Available at http://www.presidency.gov.gh/sites/default/files/ndc_manifesto_General%20agenda%20Prez%20Mills.pdf

Tetteh, B (2013, April 30). 'Transport Minister Inspects land for New International Airport' Joy News. Retrieved from http://business.myjoyonline.com/pages/news/201304/105292.phpAccra.

See story above.

Refer to the story in second endnote.

Bernama, NNN. 'Ghana Signs MoU With Chinese Firm To Build New Airport For Accra' Ghana New Agency. October 11, 2012. Accessible at http://aviation.bernama.com/news.php?id=701222&lang=en. It will not be wrong for one to conclude from this story and the one following, that both contracts for the design and construction of the new airport have already been awarded by the government of Ghana, merely by looking at the titles, though their actual contents confirm these.

China to Construct Ghana's 2nd International Airport' (2013, February 19). Economic Tribune. Retrieved from http://business.peacefmonline.com/news/201302/156674.php?storyid=100&

'New International Airport takes off'. (2013, February 21). The Al Hajj. Retrieved from http://vibeghana.com/2013/02/21/new-international-airport-takes-off

See the story published on MYJOYONLINE on April 30, 2013at http://business.myjoyonline.com/pages/news/201304/105292.phpAccra.

Defined as the zone between Accra-Tema, Kumasi, and Sekondi-Takoradi, respectively the first, second and fourth largest urban centres in Ghana, the golden triangle is estimated to accommodate over 80 percent of Ghana's industrial activity, non-farm employment, tertiary institutions (both public and private).

Most urban centres, especially large ones, have two boundaries: 1. political or administrative boundaries which defines the delimitation of political authority in the city, and 2. functional region or boundaries which cover the full extent of activities and linkages between the central city and neighboring settlements, towns or cities outside it administrative boundaries but together form a contiguous pattern of settlements. Underbounding is a term used to describe the situation whereby a city bursts its political borders. A city-region or mega urban region emerges where several administratively distinct urban centres coalesce into a single, large-scale polycentric city with shared resources, common labour market and several linkages, including transportation, population and goods flows.

According to the former minister of transportation, Alhaji Collins Dauda, there is 'the need to construct another international airport in the green belt as an alternative to the KIA', confirming my earlier suspicion that the proposed project site at Prampram is found in a greener ecological landscape than a likely northern location (see the story as published in the August 5, 2012 edition of the Daily Graphic and cited in footnote 8 above).

President Mahama launches National Urban Policy'. (2013, March 28). JoyNews. Retrieved from http://m.myjoyonline.com/pages/edition/news/201303/103534.php

Mahama, J. (2013, April 30). 'Urbanisation could cripple Africa's Growth'. Keynote Address at the third Times CEO Summit Africa. London, UK . Retrieved from http://edition.myjoyonline.com/pages/news/201304/105277.php

Urban transition is the reconfiguration of society from a predominantly rural population to a predominantly urban one, such that more than half of the population now resides in citied. Urban transition is not just a movement or relocation of people from villages to cities; in some cases, it may come about as a result of the 'movement' of the city into rural areas, i.e, urbanization of the countryside, as is happening in China today, although in realty both processes and forces are always at work in tandem. However, it entails fundamental shifts in the socio-economic structure and culture of a society, including changes in economic activities (mainly from agriculture to manufacturing and services); lifestyle shifts, typified by greater consumption, possession of material goods, desire for smaller family sizes, and a general compartmentalization and complexification of relationships and attitudes; as well as institutional and political changes, including the rise a vocal civil society and political pluralism and administrative decentralization. Unlike the experience in developed countries, whereby the movement from ruralism to urbanism was characterized by all of the above, and occurred slowly over a longer period of time, in the developing world this has not been the case, as the transition has been rapid and mostly been limited to rural-urban migration without any corresponding growth and changes in the economy in particular. This has raised concerns about the desirability and sustainability of Africa's (including Ghana's) massive urbanization, due to consequences of high unemployment, slum proliferation, congestion, informality and crime, to mention a few.

Meta releases new version of conversational AI across its platforms

Meta releases new version of conversational AI across its platforms

Cape Town named Africa’s Best Airport 2024 by Skytrax

Cape Town named Africa’s Best Airport 2024 by Skytrax

Bono East: Four injured after hearse transporting corpse crashes into a truck

Bono East: Four injured after hearse transporting corpse crashes into a truck

‘Be courageous, find your voice to defend our democracy’ — Sam Jonah urges journ...

‘Be courageous, find your voice to defend our democracy’ — Sam Jonah urges journ...

Exodus of doctors, nurses and teachers have worsened because of unserious Akufo-...

Exodus of doctors, nurses and teachers have worsened because of unserious Akufo-...

2024 election: Avoid insults, cutting down people in search of power – National ...

2024 election: Avoid insults, cutting down people in search of power – National ...

‘You passed through the back door but congratulations’ — Atubiga on Prof Jane Na...

‘You passed through the back door but congratulations’ — Atubiga on Prof Jane Na...

Government’s $21.1 billion added to the stock of public debt has been spent judi...

Government’s $21.1 billion added to the stock of public debt has been spent judi...

Akufo-Addo will soon relocate Mahama’s Ridge Hospital to Kumasi for recommission...

Akufo-Addo will soon relocate Mahama’s Ridge Hospital to Kumasi for recommission...

We must not compromise on our defence of national interest; this is the time to ...

We must not compromise on our defence of national interest; this is the time to ...