The German Social Democrat party (SDP) that narrowly beat outgoing German Chancellor Angela Merkel's CDU/CSU bloc has started to look for a rapid coalition deal, worried that weeks of uncertainty could spell trouble for Europe's biggest economy.

"It's like a Turkish bazaar," Gero Neugebauer, a political scientist affiliated with the Freie Universität Berlin told RFI.

"You have to make an agreement that allows every party to keep its political identity, but on the other side to agree to goals and political methods which they didn't agree on during the campaign. It all depends on the willingness of those who want to form the government," he says.

"The election results changed the German party system," he added.

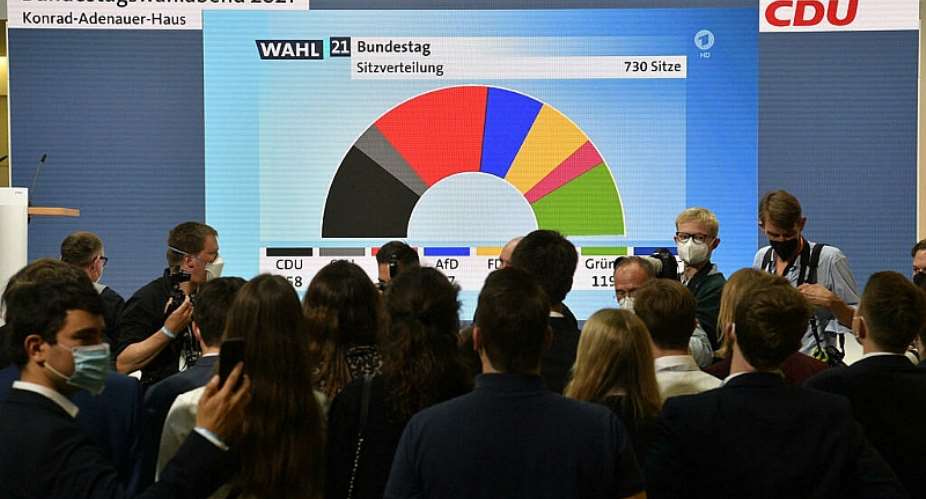

"There is no longer one big party, which is able to take a smaller one and go into a coalition government. It's the first time in German history that they have to form a coalition consisting of three partners.

Olaf Scholz, the candidate for the center-left Social Democrats, called for Merkel's center-right Union bloc to go into opposition after it saw its worst-ever result in a national election.

Both finished with well under 30% of the vote, leading to two smaller parties - the Greens and the Liberal FDP - to become kingmakers.

"The bad side of this coalition building will be that we are going to be a little bit more Dutch," says Bernard Hütteman, Secretary General of the European Movement Germany, an organisation which promotes increased European integration, referring to the Netherlands, which still doesn't have a government after elections in March.

"We need a little bit more time to create a coalition here in Germany."

Core of the EU

The lack of a clear winner in the elections, combined with the upcoming presidential elections in France next April create uncertainty in the two main economic and political powers at the core of the EU. It comes as the bloc faces a resurgent Russia and increasing questions about its future from populist leaders in eastern countries.

"We want to see coherence within the government, but also within the European Union; there should be coherence in dealing with [foreign policy issues such as] China and the trans-Atlantic relationship," adds Hütteman, referring to growing discontent from Brussels with Beijing, as well as friction between the US and Russia.

What now for Merkel?

Merkel stepping down as Germany's chancellor is the end of an era, and the country will have to get used to politics without her "motherly" approach. The question remains: Will she be able to leave politics alone?

"Merkel is Merkel," says Hüttemann. "She will rather read a book, then write a book. So for her, it's very important that she comes down a little bit. She's expressed this as much, and everybody loves her for this. She might come back in a very strange position. But I don't see that this is her priority," he says.

"There may be a role to play for her as an "elder stateswoman," says Neugebauer, pointing at her unrivalled experience in crisis management on an international level.

"She will stay out of domestic politics, but may intervene in international politics. But only on invitation, for instance, by the United Nations or possibly by European Parliament or the European Commission," he says.

Ghana will make maiden voyage into space should Bawumia become President — Chair...

Ghana will make maiden voyage into space should Bawumia become President — Chair...

Train crash: Despite the sabotage, we shall not be deterred and will persevere —...

Train crash: Despite the sabotage, we shall not be deterred and will persevere —...

Tema-Mpakadan railway project a perversion of the original viable concept design...

Tema-Mpakadan railway project a perversion of the original viable concept design...

Train crash: Elsewhere, everyone involved in the test will either be fired or re...

Train crash: Elsewhere, everyone involved in the test will either be fired or re...

Ghana, other election bound-countries must build fiscal buffers – IMF admonishes

Ghana, other election bound-countries must build fiscal buffers – IMF admonishes

Parliament reconvenes late May, denies Speaker Bagbin delaying recall over NDC t...

Parliament reconvenes late May, denies Speaker Bagbin delaying recall over NDC t...

$100m needed to revitalise Ghana's poultry sector — GNAPF

$100m needed to revitalise Ghana's poultry sector — GNAPF

Driver arrested for causing train collision on Tema-Mpakadan Railway Line

Driver arrested for causing train collision on Tema-Mpakadan Railway Line

Police grab trucker for Tema-Mpakadan rail accident

Police grab trucker for Tema-Mpakadan rail accident

Gov't plans to revise traditional customs following Gborbu child marriage

Gov't plans to revise traditional customs following Gborbu child marriage