ABSTRACT: Cote d'Ivoire is not justified for making an overlapping claim over the oil and gas deposit at Cape three point (Jubilee Field) after Texas based Oil Company, Kosmos discovered oil at the Ghana part. The Government of Ivory Coast mapped out a new maritime border it is sharing with Ghana covering some of Ghana's Jubilee oil field and has therefore publicly challenged Ghana over title to the offshore acreage hosting some of the prolific oil and gas field. It is believed that the disputed border hold about a billion-barrel discoveries. However, Ghanaian Government debunk the claim that Ivorians are being opportunistic and argued that both countries had always respected the median line until Oil was found at the Ghana part of the maritime border, Ivory Coast is making a claim disrespecting this Median line both country respected. Also, Ghana and Cote d'Ivoire has straight based lines which are demarcated by pillars from the Atlantic Ocean. With the intervention of ECOWAS and AU which both countries are members, Ghana has proceeded with E&P process and Cote d'Ivoire has petitioned the International Court of Justice to fast tract with the boundary delimitation.

1.0 INTRODUCTION

Border disputes are infamously not easy to resolve. International laws do not contain a clear set of rules established through international conventions or jurisprudence determining States sovereignty over territory in the countenance of competing realistic claims, e.g based on civilizing, cultural, chronological, religious, and other political, economic, and social factors. Coastal States are not willing to lose cases since they may suffer political penalty as well as loss to national interests.

BDs often come up after they are link with important economic or social interests. Disputed areas may contain some important natural's renounces like oil and gas, metallic noodles, or transboundary aquifers that provide access to the sea, such as grazing areas; or be a considered location.

Competition for shared or transboundary resource has become more intense among Coastal states in recent years due to economic developments, such as higher oil and gas prices, and climate change, such as limited land for agriculture, excessive use of land and deforestation, as well as regional and global desertification. They are a lot of factors that makes it difficult for States involved in a BD to resolve it among themselves and are unwilling to make their submissions to the International court of justice.

Many supportive approaches to resource and border issues have been implemented by states on an agreed basis or as a result of dispute resolution assistance. Examples of such include: joint development and exploitation of competed or shared resources, including oil and gas reserves or fish stocks; joint operating agreements, or cooperative sharing, of SRs, such as establishing rules and regulations or negotiated access to the sea for landlocked states or through territorial waters for neighboring states; rites of passage and transit for states with noncontiguous territories and or commitments to obey the cultural, historical, or social heritage, as well as political autonomy of national minorities. The research paper will analyze the median line method of delimitation considered by International law and States for delimitation of maritime boundaries of opposite states. Is Cote d'Ivoire justified using the median line method?

2.0 MARITIME BOUNDARY DELIMITATION: GEOPOLITICAL, ECONOMIC AND LEGAL ASPECTS.

Disputes over maritime boundaries are common among geopolitical landscape in Africa posing a serious challenge to political stability and often been a source of disagreement among Coastal States.

The African Continent is not strange to conflict and transboundary disputes over natural resources. The recent diamond conflict in Sierra lone and the Niger Delta in the 1990s are few examples of boundary disputes. Nigeria and Cameron clashed several times over hydrocarbons deposits in the Bakassi Pennisular.

The conflict was settled by the International Court of Justice in the Hague when many people were killed. These conflicts occur among Coastal states when they intent to keep their territorial sovereignty intact, ensure human security, economic stability including the need to benefit financially from the sale of these reserves. In the past, dispute between Botswana and Namibia over hydrocarbons deposit in Sedudu Island in the Chober River. This was peacefully settled in 1999 by the International Court of Justice.

Resources scarcity enhances the possibility for boundary conflict in the study and literature of international law. According to Choucri and North (1975 and 1989) contended that internal demands on resources push States toward outward expansions in increasing the possibility for conflict to arise through hostile pressure.

Robert Thomas Malthus also argued that, population growth and high resource consumption per capita (demand-induced scarcity) leads to deteriorated environmental conditions (supply-induced scarcity), which increase resource scarcity further and create harsher resource competition. This process, when combined with inequality with respect to resource access (structural scarcity), increases the chances for violence (Gleditsch, 2001, p. 253).

There is a link between resources scarcity and territorial disputes. This involves real threats to agricultural and industrial production, as well as national security. Obviously, as population increases the demand for resources increases. If Coastal states are opposite and one is relatively rich to resources poor states, a dependency relationship is likely to be established on both sides of the boundary. Control over the cross-border resources by one party usually indicates a decrease in the border. There is a common argument that, resources directly results in conflict when they are becoming increasingly scarce in the region, when they are essential for human needs and can be physically seized or controlled. Critchley and Terriff (1993, pp. 332–3) assert that direct conflict over renewable resources might be rare, but competition over scarce resources would have a strong indirect effect on the propensity for conflict.

Disputes over maritime boundary and islands often stem from historical and cultural claims; sometimes they may also emerge as a result of fundamental geopolitical changes. Just as on land, in certain circumstances. Maritime boundaries and island disputes may even evolve into situations of power rivalry competition for scarce seabed resources. There is an intensifying “tit for tat” claims between Ghana and Cote d'Ivoire for hydrocarbons deposit and exploration in the Cape three points of Ghana could be just an example. Fortunately, both States are leading and respected members of ECOWAS as well as the Africa Union and could use these regional institutions to peacefully settle any disputes they may have. Additionally, there is international laws, regulations, conventions, and institutions which determine who is entitled to which asset on land and on the seabed. Such rules and frameworks provide means and guidelines on how disputes could be determined or settled in international courts. Both Cote d'Ivoire and Ghana are signatories to these international conventions including UNCLOS, which forms the basic rules and regulations among others the navigational rights, territorial sea limits, economic jurisdiction, legal status of resources on the seabed beyond the limits of national jurisdiction, passage of ships through narrow straits, conservation and management of living marine resources, and protection of the marine environment. Both countries should use these conventions to address their concerns. Besides, using diplomacy and international legal system, both countries can choose cooperation: joint development, unitization and joint management of the disputed area(s) for the benefit of these countries.

6 Jared Bissinger., Maritime Boundary disputes between Bangladesh and Myanmar: Motivation Potential solutions and implications. National Bureau of research. Asia Policy number 10 Research Notes (July 2010)103-42.

7 Aikin. A., Oil and Gas at Ghana-Ivorian border: conflict or cooperation.(Article) pages1-4 (2012)

8 Guo. R., Territorial disputes and seabed petroleum exploitation: some options for the East China Sea. Professor and Head of the Regional Economics Committee of the Regional Science Association of China,

9Peking University CNAPS Visiting Fellow China, The booking institution Center for north Asian policy studies, page 4-5 (2010).

10Gleditsch.P., Globalization and armed conflict, page 22 (2001)

11Crichley and Terriff, Global insurgences and the future of armed conflict, page 332-3(1993)

3.0 ORIGIN AND DEVELOPMENT OF THE GHANA-COTE D'IVOIRE DISPUTE

In 2007 the media reported that Cote d'Ivoire which shares maritime boundary with Ghana is making overlapping claims to parts of the sea where Ghana has recently discovered oil. The report saw Ghanaians pouring in on online chat rooms and radio discussions in solidarity of their country. They condemned the Ivorian claims as opportunistic.

Mr. Collins Dauda, Ghana's Lands and Natural Resources Minister buttressing the point that, Ivoirians are being opportunistic, “argued that there was no maritime dispute between Ghana and Cote d'Ivoire, and that both countries had always respected the median line until O&G was found in the Ghana part of the maritime border”. “All of a sudden, with the oil find, Cote d'Ivoire is making a claim that is disrespecting this median line we have all respected. In which case we would be affected or the oil find will be affected” the Minister claimed. Mr. Dauda was right about this “no maritime dispute” statement. Both countries have been good neighbours ever since gained independence. Both nations are trading partners. There is no memory of a major armed confrontation between the two sister nations. In 2011 Ghana even petitioned efforts by regional bloc ECOWAS to invade Cote d'Ivoire after the disputed elections. The government of Ghana argued, at that time that war was not necessary and that dialogue should be used to settle the marine time dispute.

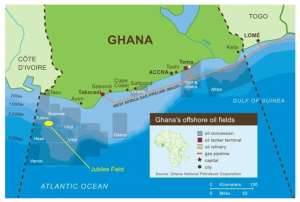

On the 29th of November 2011, the Government of Cote d'Ivoire led by President Allasane Ouattara mapped out a new maritime border covering some of Ghana's jubilee oilfields. Cote d'Ivoire publicly challenged Ghana over title to the offshore acreage hosting some of the most prolific oil and gas fields. It is believed that the disputed border hold about a billion-barrel discoveries according to Upstream news publication, (2010). Tweneboa, Enyenra and Owo discoveries, among others, plus the West Tano-1X find and several prospects.

Figure (1) Controversial Maritime boundary mapped by Cote d'Ivoire

Source: (Hobotraveler.com)

Talks between Ghana and CDV is still pending, Ivory Coast planned to develop its own gas processing infrastructure, duplicating proposal advanced by Ghana, this move was a political posturing ahead of a diplomatic solution to the maritime border impasse.

The Head of the Technical committee of the presidential commission, Mr. Lawrence Apaalse told Ghanabusinessnews.com on June 26, 2010 that “Ivorians made some proposals to Ghanaian commission, but were not acceptable and they were asked to go back home and review it”.

Meanwhile, Texas based oil explorer, Kosmos Energy has expressed fears about the development. The oil producers say the future of a portion of its license in the deeper water Tano Block is uncertain as the issue remains unresolved.

Currently, Ghana is the rightful owner of the area, but CDV has petitioned the United Nations to demarcate the Ivorian territorial maritime boundary with Ghana.

12Emmanuel, K.D., and Ekow, .Q. Ivory Coast unveils controversial maritime border with Ghana covering prolific jubilee field deposit talks ongoing. Ghana businessnews.com (November, 29 2011)

See Supra note 3

4.0 INTERNATIONAL LEGAL REGIME OF MARITIME BOUNDARIES DELIMITATION

Prior to 1945, there was variety in Coastal State's practice with respect to claiming maritime zones in which they could exercise full sovereignty over the seabed and subsoil, the water column, and the airspace. After World War II, the situation has changed. The scarcity of land-based natural resources forced States to concentrate on the exploitation opportunities of offshore resources. Technological progress had shown the potential importance in this respect of the natural resources of the continental shelf. Furthermore, States began to realize the growing importance of the non-living resources of the high seas as being vital to their economic development. These factors resulted in the emergence of the new concept, the continental shelf (CS). The law of the sea is one of the oldest branches of international law, however, the most important source of codification and progressive development of this law were the three United Nations Conferences held in 1958, 1960 and from 1973 to 1982 respectively .

The IL of the sea has always been characterized by the attempts of states to assert their control and jurisdiction over the maritime space adjacent to their coasts. Despite the fact that the Law of the Sea Convention (LOSC) has prescribed, though not always with clarity, the rights and jurisdictions enjoyed by coastal states in the various maritime zones.

a). 1982 UN Convention on the Law of the Sea

Control over the world's oceans has been a source of international debate since the early seventeenth century. Maritime powers have traditionally sought to maximize the 'freedom of the seas' and, until the late nineteenth century, state coastal state jurisdiction offshore was generally limited to a narrow band of coastal waters determined by the so-called 'cannon-shot rule' − the distance out to sea that a cannon ball fired from the shore could reach. However, the twentieth century witnessed a dramatic expansion of state control over maritime space, with some states claiming sovereign TS extending as far as 200 nm from their coasts (Dewey and Leboeuf 2007). A series of international conventions signed in Geneva in 1958 were partially successful in codifying the law of the sea, but it was not until 1982 that a comprehensive regime for the world's oceans was agreed in the form of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea.

Coastal states are entitled to claim rights over the resources of the sea and seabed up to at least 200 nautical miles from their coast and in the case of the seabed, potentially much further. As a result, more than 30% of the world ocean now fall under state jurisdiction, with overlapping maritime zones creating the need for 430 international maritime boundaries, fewer than half of which have been partially agreed (AIPN Reports 2007). With the O&G industry operating in ever-deeper water, E&P companies increasingly find themselves interested in areas over which two or more states claim jurisdiction. UNCLOS as the 1982 convention is commonly is perhaps the widest ranging and sophiscated treaty ever agreed by IL, according to the 2007 AIPN reports. Comprising 320 articles and nine annexes, UNCLOS not only codifies the principles of maritime jurisdiction and boundary delimitation; It also provides the international legal frame work governing issues such as navigation, maritime scientific research, the utilization of living and non -living resources, the protection and preservation of marine environment and the settlement of oceans related disputes. Although UNCLOS was signed by 119 states when it was opened for signatory in 1982, it did not enter into until November 1994 when the sixtieth instrument of ratification or accession was deposited with the United Nation.

13 Dewey and Leboeuf LLP., How to deal with maritime boundary uncertainty in oil and gas exploration and production areas. (A paper prepared for the association of international petroleum negotiators). (International boundary research unit pages 1,2 and 3 (2007)

14 Dr. Kopela.S., The territorialization of the exclusive economic zone: implication for maritime jurisdiction, International boundary research unit. Page 1 (2009).

15 UNCLOS article 15 33, part ii and v

(b). 1958 Geneva conference on the Law of the Sea

The General Assembly of the United Nations by its Resolution 1105(xi) adopted on February, 21 1957 called for a conference of its members to examine the law of the sea taking accounts not only of the legal but also the technical, biological, economic and political aspects of the programme and to embody the results of its works in one or more international conventions or results. The Geneva conference on the law of the sea was convened on February 24, 1958. Four conventions emerged from the conference after much discussions, debate and toil and are now subject to ratification. These conventions are the territorial sea, continental shelf, exclusive economic zone, and contiguous zone and high seas conventions and encompassed a surprisingly large area of agreement. The GC had the benefit of six sessions of prior work by international law commission. The final report of that commission produced in its eighth session set forth articles with commentary. The major problem facing the conference appeared to be the determination of the legal limit of the territorial sea appertaining to a coastal state (Aurther HD 1958). The USSR block was insisting for military reasons on the 12 miles or greater territorial sea breadth which of course had not been recognized by international law. Chile Ecuador and Peru had claimed 200miles territorial sea or of exclusive jurisdiction. The USA together with Great Britain, Japan Holland, Belgium Greece, France, and West Germany adopted it as first goal in the conference, the preservation of the traditional limit of the territorial sea at three miles.

16Arthur. H. D., The Geneva conference on the law of the sea: What was accomplished. (America journal of international law) America society of international law. vol. 52 No 4(Oct. 1958) pp 607-628 (22pages)

17Philip C. J., The Geneva conference on the law of the sea: A study in international law making. America journal of international law making. Vol 52 No. 4(oct.1958)pp 730-733

18Tullio. T., Judge of the international tribunal for the law of the sea, 1958 Geneva Convention on the law of the sea,

19 (United Nations Audiovisual Library of International Law), page 1(2008)

20 58 Geneva convention on the territorial sea and continental shelf and contiguous zone, article 12

21 1958 Geneva convention on the continental shelf, article 6

5.0 BRIEF HISTORY OF GHANA-COTE D'IVOIRE BOUNDARY

The Ghana-Cote d'Ivoire boundary extends for approximately 415miles between the Gulf of Guinea and tripoint with Upper Volta. It follows various rivers including, in the northern sector, the thalweg of the Black Volta about 70miles. More than half of the boundary consists of straight-lines segments which are demarcated by pillars.

Prior to the independence of Ghana and CDV, Anglo-French treaties determined the present day boundary between the two African states. Ghana became an independence state on March 6, 1957 when the United Kingdom relinquished its control over the colony of the Gold Coast and Ashanti. On December 4, 1958, the Ivory Coast became an autonomous republic within the French community and on August 7, 1960 the republic of the Ivory Coast was proclaimed independence under the terms of an accord with France. Established in 1968, a demarcation commission for Ghana-CDV boundary has met regularly since 1970. An Anglo-French arrangement of August, 10 1889, stated that the boundary between their respective possessions on the Gold Coast started at Newtown and extended inland to the Lagune Tendo. It then followed successively the left banks of the Lagune Tendo, the Lagune Ehy, and the Tendo river to Nougua. The boundary was to continue northward to the 9th Parallel in accordance with various treaties concluded by British and French Government with local chiefs.

On June 26, 1891 an agreement was signed by the United Kingdom and France, which delimited in details the boundary from Nougoua to the 9th Parallel, with northern sector following the Black Volta.

The United Kingdom and France concluded an arrangement on July 12, 1889, delimiting the boundary between the Gulf of Guinea and the 9th parallel in greater details than had previously been the case. Separate frontiers were delimited for the British and French possessions between Lagune and Tendo and Nuogoua.

22 Note that the thalweg of the Tano is indicated as the boundary, rather than the French frontier following the right bank of the Tano and the British frontier the left bank as delimited in the arrangement of 1893.

23The tripoint with Upper Volta is located on the thalweg of the Black Volta at approximately 9o29'30" N.

24 From this point northward to the 11th parallel, the thalweg of the Black Volta forms part of the present-day

Ghana–Upper Volta boundary.

25 Department of State, United state of America,. International boundary study, Cote D'Ivoire (Ivory Coast)-Ghana boundary. The Geographer office of the geographer, Bureau of intelligence and research. No. 138-July 16, 1973(pages 1-18)

5.0 The median line method on international law to the Ghana-Cote d'Ivoire border dispute

Article (74) and 83(1) of UNCLOS the 1982 Convention lay down the law applicable in the determination of the continental shelf and Exclusive economic zone respectively. In the case with states with either opposite or adjacent Coast, the delimitation of such maritime area shall be effected by agreement on the basis of international law as referred to Article 38 of the Statute of International Court of justice in order to achieve an equitable distribution. IL permits a state to extent its EEZ seaward to a distance of 200nautical miles from its baseline as defined by article 57 of the 1982 LOS convention. Also, the continental shelf seaward extension is at 200nautical miles from the baseline and perhaps considerably farther when international law so permits.

Those maritime zones of two States frequently meet and overlap, and the line of separation has to be drawn between the states. IL of the sea also stresses that neither of the two states is entitled, failing agreement to the contrary to extend its territorial sea beyond the median line. Therefore delimitation is a process involving the division of maritime areas where two or more states having competing claims. For both states this act may imply restriction their perceived sovereignty.

The delimitation process itself involves several types of issues. One concern is the source of authority. A second issue involves the principal method by which delimitation is carried out and finally there are technical questions regarding the determination of the actual lines in space. Ghana and Cote d'Ivoire have not delimited their offshore boundaries in the Gulf of Guinea. Both countries have ratified the 1982 UN convention on the law of the sea. Ghana and CDV officially recognizes the median line as the limit of their jurisdiction. There is evidence that Ghana also takes this vis-a vis Togo and Benin.

Figure (2) The Jubilee Unit area

Source GNPC, (2009).

Cote d'Ivoire has asked the international court of justice to decide the course of the Ghana-Cote d'Ivoire offshore boundary, the sovereignty of the Cape three points (Jubilee filed) and the course of their maritime boundary.

26 Daniel J.,Gulf of Guinea boundary dispute.( Article ) pages 98-1049( 2009)

27GNPC, 2009 Exploration and production history of Ghana htt://www.gnpc.com/

28Jared B., The maritime boundary dispute between Bangladesh and Myanmar; Motivation, potential solutions and implication. (Asia policy No. 10 July 2010) 103-42

29Nugzar. D., Delimitation of maritime boundaries between adjacent States.(United Nations-The Nippon Foundation Follow, University of Georgia (2006-2007) Pages 2-3

Figure(2)The Outer limit of Ghana's Continental Shelf

(Source) Submissions by the Republic of Ghana on the outer limit of the CS to (ICJ)

Ghana is a West African Coast state with a population of 20,467,940 bordering the Gulf of Guinea along a 538km long Coastline between Togolese Republic and the Republic of Cote d'Ivoire. The total land area including Lake Volta is 239,460km.

As provided for under Paragraph 1 of Article 76 of the convention, Ghana has a continental shelf comprising the seabed and subsoil of two submarine areas that extend beyond its territorial sea throughout the natural prolongation of its land territory to the outer edge of the continental margin up to the limit provided for in Paragraph 4 to 6 of Article 76 or to a distance of 200m from the territorial sea baseline of Ghana where the outer edge of the continental margin does not extend beyond that distance. Ghana Eastern extended continental shelf encloses an area of 9387.8km² beyond 200 nautical miles from the baselines. Ghana has the Eastern extended and the Western extended continental shelves regions. Ghana has overlapping maritime claims with Cote d'Ivoire to the Western extended continental shelf and encloses an area of 4,741.8km² beyond 200m from the territorial sea baseline. Cote d'Ivoire has overlapping claims with maritime claims with adjacent states in the region, but has not signed any maritime boundary delimitation agreement with any of its neighbouring states to date.

(b). The Outer limit of Cote d'Ivoire Continental shelf

Cote d'Ivoire is a West African coastal state with a population of 18,373,060 bordering the Gulf of Guinea along a 520km long coastline between Liberia and Ghana. The total land area is 322,462km². Cote d'Ivoire is a contrasting party to the convention having signed the convention on December 10th 1982 and ratified in March 1984.

As provided for under Paragraph 1 of Article 76 of the convention. Cote d'Ivoire has a continental shelf: comprising the seabed and subsoil of a submarine area that extend beyond its territorial sea throughout the natural prolongation of its land territorial to the outer edge of the continental margin. This extends up to the limits provided for in Paragraphs 4 to 6 of Article 76 or to a distance of 200m from the territorial sea baseline of Cote d'Ivoire where the outer edge of the continental margin does not extend beyond that distance.

d. Ghana-Cote d'Ivoire maritime boundary situation (Opposite and Adjacent Coast)

Figure (3) Opposite Coast of Ghana and Cote d'Ivoire

Source (Kojo Bentsi-Enchill presentation on 8th Maritime law seminar in Ghana some issues in Ghana oil and Gas law).

The Western continental shelf of Ghana overlaps with that of CDV and encloses an area of 4741.8km² beyond 200nm from the territorial sea baseline. The delimitation of Ghana and Cote d'Ivoire continental shelf, the opposite and adjacent coast should be effected by agreement on the basis on international law as referred to in Article 38 of the status of international court of justice.

6.0 Conclusion

The forgoing considerations allows for conclusion that Cote d'Ivoire is not justified for making competitive claims of oil and gas deposit at Cape three points (Jubilee Field). Cote d'Ivoire and Ghana are opposite Coastal states and recognized the median line as the official boundary of jurisdiction. Also, Article 7 of UNCLOS talks about straight baseline for measuring the breadth of the territorial sea. Ghana and Cote d'Ivoire has a straight baseline are demarcated by pillars.

However, Cote d'Ivoire and Ghana has petitioned the International court of justice to fast tract the maritime boundary delimitation between the two coastal states after making submissions since both parties has ratified UNCLOS. In addition, with the intervention of ECOWAS and AU which both parties are members, Ghana has since asked its oil producers to start the E& P process as they await the judgment of the International court of justice.

The median line method does not lay down obligations, but simply clarifies the guidelines for achieving equitable results in the delimitation and are relevant for particular case. At the same time, case law and especially State practice support the use of the median line circumstance rule and show that primacy must be accorded to the geographical factors in delimiting maritime boundaries. The primary rule for maritime delimitation accepted both conventional and customary law is that the delimitation must be effected by agreement.

,

ARTICLE IS WRITTEN BY MR RAPHAEL KUNSU

MSc. Energy and the Environment

UNIVERSITY OF DUNDEE, SCOTLAND

7.Biobliograhy

International Journals

Arthur. H. D., The Geneva conference on the law of the sea: What was accomplished. (America journal of international law) America society of international law. vol. 52 No 4(Oct. 1958) pp 607-628 (22pages)

Philip C. J., The Geneva conference on the law of the sea: A study in international law making. America journal of international law making. Vol 52 No. 4(oct.1958)pp 730-733

UNCLOS Article 15 33, part II and V

1958 Geneva Convention on the continental shelf, article 6

(United Nations Audiovisual Library of International Law), page 1(2008)

1958 Geneva Convention on the territorial sea and continental shelf and contiguous zone, article 12

Tullio. T., Judge of the international tribunal for the law of the sea, 1958 Geneva Convention on the law of the sea,

Books

Crichley and Terriff, Global insurgences and the future of armed conflict, page 332-3(1993)

Department of State, United state of America,. International boundary study, Cote D'Ivoire (Ivory Coast)-Ghana boundary. The Geographer office of the geographer, Bureau of intelligence and research. No. 138-July 16, 1973(pages 1-18)

Gleditsch.P., Globalization and armed conflict, page 22 (2001)

GHA-DOC-ES, Submissions by the republic of Ghana for establishment of the outer limit of the continental shelf of Ghana pursuant to Article 76 paragraph 8 of UNCLOS

CI-DOC-E Submission by the republic of Cote d'Ivoire for the establishment of the outer limit of the continental shelf on the continental shelf of Cote d'Ivoire pursuant to Article 76 paragraph 8 of UNCLOS.

Articles

Aikin. A., Oil and Gas at Ghana-Ivorian border: conflict or cooperation.(Article) pages1-4 (2012)

Daniel J.,Gulf of Guinea boundary dispute.( Article ) pages 98-1049( 2009)

Guo. R., Territorial disputes and seabed petroleum exploitation: some options for the East China Sea. Professor and Head of the Regional Economics Committee of the Regional Science Association of China,

Peking University CNAPS Visiting Fellow China, The booking institution Center for north Asian policy studies, page 4-5 (2010).

Dewey and Leboeuf LLP., How to deal with maritime boundary uncertainty in oil and gas exploration and production areas. A paper prepared for the association of international petroleum negotiators. International boundary research unit pages 1,2 and 3 (2007)

Dr. Kopela.S., The territorialization of the exclusive economic zone: implication for maritime jurisdiction, International boundary research unit. Page 1 (2009).

Emmanuel, K.D., and Ekow, .Q. Ivory Coast unveils controversial maritime border with Ghana covering prolific jubilee field deposit talks ongoing. Ghana businessnews.com (November, 29 2011)

Jared Bissinger., Maritime Boundary disputes between Bangladesh and Myanmar: Motivation Potential solutions and implications. National Bureau of research. Asia Policy number 10 Research Notes (July 2010)103-42.

Kojo B. Enchill, Presentation on some issues in Ghana oil and gas law(8th maritime seminar) Slide 16

Nugzar. D., Delimitation of maritime boundaries between adjacent States.(United Nations-The Nippon Foundation Follow, University of Georgia (2006-2007) Pages 2-3

The Carter Center, Approach to solving territorial conflict. Source, situations, scenarios and suggestions (The Carter Centre, One Copenhill 453 Freedom Parkway, Atlanta GA 30307 page 1 (May 2010).

GNPC, 2009 Exploration and production history of Ghana htt://www.gnpc.com/

Kojo B. Enchill, Presentation on some issues in Ghana oil and gas law(8th maritime seminar) Slide 16

"This nonsense must stop" — Lawrence Tetteh vows to march to Jubilee House over ...

"This nonsense must stop" — Lawrence Tetteh vows to march to Jubilee House over ...

2024 elections: “If indeed you stand for peaceful elections the time is now for ...

2024 elections: “If indeed you stand for peaceful elections the time is now for ...

I have the attributes to be president of this country — Bernard Monarh

I have the attributes to be president of this country — Bernard Monarh

Cecilia Dapaah saga: ‘Turf war’ between AG, EOCO, OSP indicates they’re not ‘cor...

Cecilia Dapaah saga: ‘Turf war’ between AG, EOCO, OSP indicates they’re not ‘cor...

NPP digitalisation initiatives have contributed to ECG revenue collection boost ...

NPP digitalisation initiatives have contributed to ECG revenue collection boost ...

Cloudy weather to prevail across entire country tonight — GMet caution Ghanaians

Cloudy weather to prevail across entire country tonight — GMet caution Ghanaians

Bawumia promises incentives for churches; kicks against taxation

Bawumia promises incentives for churches; kicks against taxation

Current EC leadership is in the category of infamy for shady behavior, wastefuln...

Current EC leadership is in the category of infamy for shady behavior, wastefuln...

Corruption, favoritism threatens state security – Dr. Lawrence Tetteh

Corruption, favoritism threatens state security – Dr. Lawrence Tetteh

Vote for Bawumia to add to the legacy of growth, prosperity – Richard Ahiagbah u...

Vote for Bawumia to add to the legacy of growth, prosperity – Richard Ahiagbah u...