Globally, just one third of countries have achieved all of the measurable Education for All (EFA) goals set in 2000. None achieved them in sub-Saharan Africa, and only seven countries in the region achieved even the most watched goal of universal primary enrolment. Sixteen of the twenty lowest ranked countries in progress towards ‘Education for All’ are in sub-Saharan Africa. An extra $22 billion a year is needed on top of already ambitious global government contributions to ensure that the new global education targets being set for the year 2030 are achieved.

These are the key findings of the 2015 EFA Global Monitoring Report (GMR) “Education for All 2000-2015: Achievements and Challenges”, produced by an independent team at UNESCO which has tracked progress on these goals for the past 15 years.

Released today, one month before the World Education Forum in Incheon (Republic of Korea), the Report reveals the following findings for sub-Saharan Africa:

Goal 1. Expand early childhood care and education. Only seven countries in the region achieved a gross enrolment ratio of 80% or more in pre-primary education, including Equatorial Guinea, Ghana, Mauritius, Angola, Capo Verde, the Seychelles and South Africa. Only 2% were enrolled in Mali. Between 1999 and 2012, pre-primary enrolment in the region rose by almost two and half times; on average, however, only 20% of young children were enrolled in 2012.

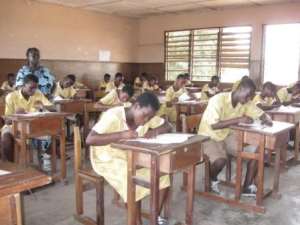

Goal 2. Achieve universal primary education: Only 7 out of 31 countries with data achieved universal primary enrolment, leaving 30 million children out of school in the region in 2012. Eight countries still have fewer than 80% of their children enrolled in primary school, including Cote-d’Ivoire, Eritrea and Nigeria. No country in the region achieved universal primary education, which means all children complete a primary school cycle. A lack of focus on the marginalized has left inequalities increasing in some countries since 2000: In Nigeria, for instance, the gap between the average and poorest households increased by about 20 percentage points between 2003 and 2013.

There have been important successes: Since 1999, the number of children enrolled in primary schools in the region increased by 75% to 144 million in 2012.

Goal 3.Ensure equal access to learning and life skills for youth and adults: South Africa and the Seychelles are the only countries to have achieved universal lower secondary enrolment. Yet there has been progress: numbers in lower secondary education more than doubled in sub-Saharan Africa since 2000. They more than quadrupled in Mozambique.

Goal 4. Achieving a 50 per cent reduction in levels of adult illiteracy: Only three countries reached this target, and three are close. Seventeen countries remain very far from it. The adult literacy rate across the region rose by only 2% since 2000, leaving 187 million adults lacking basic literacy skills, of which 61% were women. It is projected that by 2015, due to the region’s population growth, one of every four adults denied the right to literacy in the world will reside in sub-Saharan Africa, up from a fifth in 2000.

Goal 5. Achieve gender parity and equality: Twenty one countries have achieved the goal of gender parity in primary education, but in many others girls are at a distinct disadvantage relative to boys. Of the 18 countries with fewer than 90 girls for every 100 boys enrolled in primary education, 13 were in sub-Saharan Africa.

Progress towards gender parity in secondary education has been much slower, with only four countries expected to achieve parity by 2015. The poorest girls continued to be most likely never to have attended school. In Niger and Guinea, approximately 70% of the poorest girls had never attended primary school compared with less than 20% of the richest boys.

Goal 6. Improve the quality of education and ensure measurable learning outcomes for all: Sub-Saharan Africa had about 3.4 million primary school teachers in 2012, an increase of nearly 1.5 million since 1999. Despite this, teacher shortages remain a serious concern, with the region accounting for 63% of the 1.4 additional teachers needed to achieve universal primary education. Trained teachers remain in short supply: in several sub-Saharan African countries, less than 50 percent are trained. As a result, many children spend two or three years in school without acquiring basic reading and writing skills.

However, quality and learning issues have received increased attention since 2000. In addition to their participation in regional learning assessments, 60% of all countries in the region carried out a national learning assessment, up from 35% before 2000.

Funding and political will: Since 2000 many governments significantly increased their spending on education: Sub-Saharan Africa is the region where countries have allocated the largest share of government expenditure to education (18.4%), followed by East Asia and the Pacific (17.5%). South and West Asia allocated only 12.6%.

“Sub-Saharan Africa has faced many challenges in achieving Education for All. These include the effects of climate change, a fast growing population and protracted armed conflict. Economic growth in the region has not yet led to a significant reduction in poverty, which remains a major barrier to education.” said GMR Director, Aaron Benavot. “Nevertheless countries in the region have made serious commitments—financial and otherwise – to expand education opportunity and improve the quality of education. Governments must find ways, together with international partners, to mobilize new resources to quicken the pace of change in the years to come.”

The GMR makes the following recommendations:

- Complete the EFA agenda: All governments should make at least one year of pre-primary education compulsory. Education must be free: fees for tuition should be abolished; costs for textbooks, school uniforms and transport should be covered. Policy makers should prioritize skills to be acquired by the end of each stage of schooling. All countries should ratify and implement international conventions on the minimum age for employment. Literacy policies should link up with community needs. Gender disparities at all levels must be reduced.

- Equity: Programmes and funding should be targeted to meet the needs of the most disadvantaged. There should be more emphasis on gender equality, including through teacher education and safe school environments. Governments should close critical data gaps in order to be able to direct resources to those marginalized groups most in need.

- Post-2015: Countries should ensure that all children and adolescents complete pre-primary, primary and lower secondary education by 2030. Governments should significantly expand adult learning and education opportunities within a lifelong learning approach. The education sector should collaborate closely with other sectors at the national and global levels to improve sustainable development prospects.

- Close the finance gap: The international community, in partnership with countries, must find the means to bridge the US$22 billion annual finance gap for quality pre-primary and basic education for all by 2030. Clear education finance targets must be established within the Sustainable Development Goals where none currently exist.

To download the full Report, summary and other material, please visit http://www.efareport.unesco.org

To download the full Report please click here, using the password Report_EFA2015.

To directly access country-level statistics, please clickhere

Developed by an independent team and published by UNESCO, the Education for All Global Monitoring Report is an authoritative reference that aims to inform, influence and sustain genuine commitment towards Education for All.

Twitter: @EFAReport/#EduVerdict / Web: http://www.efareport.unesco.org

World Education Blog: http://efareport.wordpress.com

Akufo-Addo commissions Phase II of Kaleo solar power plant

Akufo-Addo commissions Phase II of Kaleo solar power plant

NDC panics over Bawumia’s visit to Pope Francis

NDC panics over Bawumia’s visit to Pope Francis

EC blasts Mahama over “false” claims on recruitment of Returning Officers

EC blasts Mahama over “false” claims on recruitment of Returning Officers

Lands Minister gives ultimatum to Future Global Resources to revamp Prestea/Bogo...

Lands Minister gives ultimatum to Future Global Resources to revamp Prestea/Bogo...

Wa Naa appeals to Akufo-Addo to audit state lands in Wa

Wa Naa appeals to Akufo-Addo to audit state lands in Wa

Prof Opoku-Agyemang misunderstood Bawumia’s ‘driver mate’ analogy – Miracles Abo...

Prof Opoku-Agyemang misunderstood Bawumia’s ‘driver mate’ analogy – Miracles Abo...

EU confident Ghana will not sign Anti-LGBTQI Bill

EU confident Ghana will not sign Anti-LGBTQI Bill

Suspend implementation of Planting for Food and Jobs for 2024 - Stakeholders

Suspend implementation of Planting for Food and Jobs for 2024 - Stakeholders

Tema West Municipal Assembly gets Ghana's First Female Aircraft Marshaller as ne...

Tema West Municipal Assembly gets Ghana's First Female Aircraft Marshaller as ne...

Dumsor is affecting us double, release timetable – Disability Federation to ECG

Dumsor is affecting us double, release timetable – Disability Federation to ECG