A New Worry: Prostate Cancer And Low Testosterone:

Dr. Morgentaler in the life extension magazine no longer fear that giving a man testosterone therapy will make a hidden prostate cancer grow or put him at increased risk of developing prostate cancer down the road. His real concern now is that men with low testosterone are at an increased risk of already having prostate cancer.

Dr. Morgentalerand colleagues published their results in 1996 from prostate biopsies in men with low testosterone and PSA of 4.0 ng/mL or less, the 14 percent cancer rate was several times higher than any published series of men with normal PSA. In 2006, Dr. Rhoden and Dr. Morgentaler published a larger study of prostate biopsies performed in 345 men. The cancer rate of 15 percent in this group was very similar to the first study. But whereas the cancer rate in 1996 was much higher than anything published to that date in men with PSA of 4.0 ng/mL or less, in 2006 the perspective had changed due to an important study called the Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial.

In that study, the cancer rate among men with a PSA of 4.0 ng/mL or less was also 15 percent. Because this value is identical to what they had found in their patients with low testosterone, it was suggested that the cancer rate in men with low testosterone is the same as the normal population—neither higher nor lower. However, the average age of men in their study was a decade younger than the men studied in the Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial (fifty-nine versus sixty-nine years). Almost half the men in the other study were seventy years or older, and age is the greatest risk factor we know for prostate cancer. The way he looks at these numbers is that men with low testosterone have a cancer rate as high as men with normal T who are a decade older.

More importantly, in their study of 345 men, they found that the degree of testosterone deficiency correlated with the degree of cancer risk. Men whose testosterone levels were in the bottom third of the group were twice as likely to have cancer diagnosed on biopsy as men in the upper third. This finding adds to the concern that low testosterone is a risk factor for prostate cancer.

There is now additional data from around the world associating low testosterone and worrisome features of prostate cancer. For example, low testosterone is associated with more aggressive tumors. In addition, men with low testosterone appear to have a more advanced stage of disease at the time of surgical treatment.

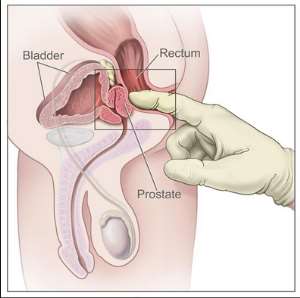

Whereas he originally began to perform prostate biopsies in men with low testosterone because he was worried that treatment might cause a hidden cancer to grow, he now perform biopsies in these men because he is concerned they might have an increased risk of cancer. This risk is approximately one in seven for men with PSA values less than 4 ng/mL.

Because prostate cancer tends to be curable when caught early, he felt he have done these men a service by finding their cancers before they have an abnormal PSA or DRE. With today's ability to monitor men with prostate cancer, not all of these men will necessarily require treatment. But the ones who have evidence of more aggressive tumors should definitely have an advantage by having their diagnosis made early.

Hormone therapy for prostate cancer

The goal of hormone therapy (also called androgen deprivation) is to lower the levels of the male hormones (androgens), such as testosterone, or to stop them from reaching prostate cancer cells.

In men, the main source of androgens is the testicles. The adrenal glands also make a small amount of androgens.

Androgens cause prostate cancer cells to grow. Lowering androgen levels or stopping them from getting into prostate cancer cells often makes prostate cancer shrink or grow more slowly for a time. Hormone therapy alone can control the cancer and help with symptoms, but at some point it will stop working. Hormone therapy cannot cure prostate cancer.

Hormone therapy is often used in these cases:

In men who can't have surgery or radiation or who can't be cured by these treatments because the cancer has already spread beyond the prostate.

For men whose cancer remains or has come back after earlier treatment with surgery or radiation.

Along with radiation as the first treatment in men who are at high risk of having the cancer return after treatment.

Before radiation to try to shrink the cancer and make treatment more effective.

Several types of hormone therapy can be used to treat prostate cancer. Some lower the levels of testosterone or other androgens (male hormones). Others block the action of those hormones.

Hormone therapy that lowers androgen levels

Orchiectomy: Even though this is a type of surgery, its main effect is as a form of hormone therapy. In this operation, the surgeon removes the testicles where most of the androgens such as testosterone are made. While this is a fairly simple operation and is not as costly as some other options, it is permanent and many men have trouble accepting this operation.

LHRH analogs (luteinizing hormone-releasing analogs): These drugs lower testosterone levels just as well as orchiectomy. LHRH analogs (also called LHRH agonists) are given as shots or as small pellets of medicine put under the skin. Depending on the drug used, they are given anywhere from once a month to once a year. Although the testicles remain in place, they will shrink over time. They may even become too small to feel.

Some LHRH analogs available in the United States include: leuprolide (Lupron®, Eligard®), goserelin (Zoladex®), triptorelin (Trelstar®), and histrelin (Vantas®).

When LHRH analogs are the first given, the testosterone level goes up briefly before going down to low levels. This is called "flare." Men whose cancer has spread to the bones may have bone pain during this flare. To reduce flare, drugs called anti-androgens can be given for a few weeks before starting treatment with LHRH analogs.

LHRH antagonists: LHRH antagonists work like LHRH agonists, but they reduce testosterone levels more quickly and do not cause tumor flare like the LHRH agonists do. Degarelix (Firmagon®) is an LHRH antagonist used to treat advanced prostate cancer. It is given as a monthly shot under the skin.

Abiraterone (Zytiga®): Even when the testicles aren't making androgens, other cells in the body can still make small amounts of male hormones. Abiraterone helps block these cells from making certain hormones, including androgens.

This drug comes in pill form. Since this drug doesn't stop the testicles from making testosterone, men who haven't had their testicles removed need to stay on LHRH agonist (or antagonist) treatment. Abiraterone also lowers the level of certain other hormones in the body, so prednisone (a cortisone-like drug) needs to be taken during treatment.

Drugs that stop androgens from working

Anti-androgens: Androgens have to bind to a certain protein in the cell in order to work. Most anti-androgens block androgens in the body from binding to that protein. This stops the androgens from working.

In the US, these drugs aren't often used alone. They are sometimes used along with orchiectomy or LHRH analogs.

Enzalutamide (Xtandi®): This drug is a newer type of anti-androgen. It doesn't block androgens from binding to the protein in the cell. Instead it stops the protein from sending a signal telling the cell to grow and divide. This can help shrink tumors and help men with advanced prostate cancer live longer.

Common side effects of hormone therapy

Orchiectomy, LHRH analogs, and LHRH antagonists can all cause side effects because of changes in the levels of hormones. These side effects can include:

Less sexual desire

Impotence (not being able to get an erection)

Hot flashes (which may get better or even go away with time)

Breast tenderness and growth of breast tissue

Shrinking of testicles

Shrinking of penis

Bone thinning (osteoporosis), which can lead to broken bones

Low red blood cell counts (anemia)

Decreased mental sharpness

Loss of muscle mass

Weight gain

Extreme tiredness (fatigue)

Increased cholesterol

Depression

An important and encouraging studies regarding testosterone and prostate cancer was an article published in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute in 2008, in which the authors of eighteen separate studies from around the world shared their data regarding the likelihood of developing prostate cancer based on concentrations of various hormones, including testosterone. This gigantic study included more than 3,000 men with prostate cancer and more than 6,000 men without prostate cancer, who served as controls in the study. No relationship was found between prostate cancer and any of the hormones studied, including total testosterone, free testosterone, or other minor androgens. In an accompanying editorial, Dr. Carpenter and colleagues from the University of North Carolina School of Public Health suggest scientists finally move beyond the long-believed but unsupported view that high testosterone is a risk for prostate cancer.

Modern issues in hormone therapy

There are many issues around hormone therapy that not all doctors agree on, such as the best time to start and stop it and the best way to give it. Studies are now looking at these issues. A few of them are discussed here.

Treating early stage cancer: Some doctors have used hormone therapy instead of watchful waiting or active surveillance in men with early (stage I or II) prostate cancer who do not want surgery or radiation. Studies have not found that these men live any longer than those who do not receive any treatment at first, but instead wait until the cancer progresses or symptoms develop. Because of this, hormone treatment is not usually advised for early stage prostate cancer.

Early versus delayed treatment: For men who need (or will eventually need) hormone therapy, such as men whose PSA level is rising after surgery or radiation or men with advanced prostate cancer who do not yet have symptoms, it is not always clear when it is best to start hormone treatment. Some doctors think that hormone therapy works better if it is started as soon as possible, even if a man feels well and is not having any symptoms. Some studies have shown that hormone treatment may slow down the disease and perhaps even lengthen survival.

But not all doctors agree with this approach. Some are waiting for more evidence of benefit. They feel that because of the likely side effects of hormone therapy and the chance that the cancer could become resistant to therapy sooner, treatment should not be started until a man has symptoms from the cancer. Studies looking at this issue are now under way.

Intermittent versus continuous hormone therapy: Nearly all prostate cancers treated with hormone therapy become resistant to this treatment over a period of months or years. Some doctors believe that constant androgen suppression may not be needed, so they advise intermittent (on-again, off-again) treatment. The hope is that giving men a break from androgen suppression will also give them a break from side effects like decreased energy, impotence, hot flashes, and loss of sex drive.

In one form of intermittent therapy, hormone treatment is stopped once the PSA drops to a very low level. If the PSA level begins to rise, the drugs are started again. Another form of intermittent therapy uses hormone therapy for fixed periods of time – for example, 6 months on followed by 6 months off.

At this time, it isn't clear that this approach is better than continuous hormone therapy, and it may even be worse in some ways. In one study of men with advanced prostate cancer, it wasn't clear that intermittent therapy helped men live as long as continuous therapy. The men on intermittent therapy also did not have much improvement in terms of side effects. While they did report fewer problems with impotence and sex drive when looked at 3 months into the study, there was no difference later on.

Combined androgen blockade (CAB): Some doctors treat patients with both androgen deprivation (orchiectomy or an LHRH agonist or antagonist) plus an anti-androgen. Some studies have suggested this may be more helpful than androgen deprivation alone, but others have not. Most doctors are not convinced there's enough evidence that this combined therapy is better than one drug alone when treating metastatic prostate cancer.

Triple androgen blockade (TAB): Some doctors have suggested taking combined therapy one step further, by adding a drug called a 5-alpha reductase inhibitor – either finasteride (Proscar) or dutasteride (Avodart) – to the combined androgen blockade. There is very little evidence to support the use of this "triple androgen blockade" at this time.

"Castrate resistant" vs. "hormone refractory" prostate cancer: These terms are both sometimes used to describe prostate cancers that are no longer responding to hormones, although there is a difference between the two.

"Castrate resistant" means the cancer is still growing even when the testosterone levels are as low as what would be expected if the testicles were removed (called “castrate” levels). This low could be from an orchiectomy, an LHRH agonist, or an LHRH antagonist. Some men may be uncomfortable with this term, but it is specifically meant to refer to these cancers, some of which may still be helped by other forms of hormone therapy, such as the drugs abiraterone and enzalutamide. Cancers that are still responsive to some type of hormone therapy are not completely "hormone refractory" and so that term cannot be used.

"Hormone refractory" refers to prostate cancer that is no longer helped by any type of hormone therapy, including the newer medicines.

In conclusion Ghanaian and black men must know that your body is a little bit like a computer. It does exactly what you “tell” it to do, but often not what you want it to do. In other words, it responds in relatively predictable ways to various diet and lifestyle changes, but not in the way that most of us want. This is what I call compensatory adaptation at work (Our body often doesn't respond in the way we expect either, because we don't actually know how it adapts; this is especially true for long-term adaptations because Okinawan, Japanese have high T level yet low risk of prostate cancer because of their reliance on traditional foods. I strongly believe that lifestyle, nutrition and exercise habits that are compatible with our evolutionary past are the key to optimal health.

What initially feels like a burst of energy soon turns into something a bit more unpleasant. At first the unpleasantness takes the form of psychological phenomena, which were probably the “cheapest” for our bodies to employ in our evolutionary past. Feeling irritated is not as “expensive” a response as feeling physically weak, seriously distracted, nauseated etc. if you live in an environment where you don't have the option of going to the grocery store to find fuel, and where there are many beings around that can easily kill you.

Soon the responses take the form of more nasty body sensations. Nearly all of those who go from obese to lean will experience some form of nasty response over time. The responses may be amplified by nutrient deficiencies. Obesity would have probably only been rarely, if ever, experienced by our Paleolithic ancestors. They would have never gotten obese in the first place. Going from obese to lean is as much a Neolithic novelty as becoming obese in the first place, although much less common.

Contrary to the postulated racial difference, testosterone concentrations did not differ notably between black and white men. However, blacks had higher estradiol levels.

Blacks have from 3 to 19% more of the sex hormone testosterone than Whites or East Asians. These testosterone differences translate into more explosive energy, which gives Blacks the edge in sports like boxing, basketball, football, and sprinting. However some of these race differences, like heavier bone mass and smaller chest cavities, pose a problem for Black swimmers.

Hormone therapy works by stopping the hormone testosterone from reaching prostate cancer cells. It treats the cancer, wherever it is in the body.

Testosterone controls how the prostate gland grows and develops. It also controls male characteristics, such as erections, muscle strength, and the growth of the penis and testicles. Most of the testosterone in your body is made by the testicles and a small amount by the adrenal glands which sit above your kidneys.

Testosterone doesn't usually cause problems, but if you have aggressive prostate cancer, it can make the cancer cells grow faster. In other words, testosterone feeds the prostate cancer. If testosterone is taken away, the cancer will usually shrink, wherever it is in the body.

Ghanaian men must be told that Hormone therapy alone won't cure their prostate cancer but it can keep it under control, sometimes for several years, before you need further treatment and it can also be used with other treatments, such as radiotherapy, naturopathic remedies to make them more effective. Low blood levels of testosterone do not protect against prostate cancer and, indeed, may increase the risk. The evidence as it stands now are high blood levels of testosterone do not increase the risk of prostate cancer.

In men who do have metastatic prostate cancer and who have been given treatment that drops their blood levels of testosterone to near zero, starting treatment with testosterone (or stopping treatment that has lowered their testosterone to near zero) might increase the risk that residual cancer will again start to grow. A variety of nutritional and herbal supplements, lifestyle habits, dietary choices, and medications can inhibit the production or reduce the levels of estrogen in the body. Because a hormone balance among testosterone, estrogen, and progesterone is important for prostate health, men should have their hormone levels checked by a physician before taking medications or supplements to alter those levels.

What you have to know is that the body is just little bit a computer and It does exactly what you “tell” it to do, but often not what you want it to do. In other words, it responds in relatively predictable ways to various diet and lifestyle changes, but not in the way that most of us want. This is what I call compensatory adaptation at work (Our body often doesn't respond in the way we expect either, because we don't actually know how it adapts; this is especially true for long-term adaptations because Okinawan, Japanese have high T level yet low risk of prostate cancer because of their reliance on traditional foods. I strongly believe that lifestyle, nutrition and exercise habits that are compatible with our evolutionary past are the key to optimal health.

Yours in Prostate Health

Dr. Raphael NyarkoteyObu :ND(TAP00396)

Integrative Oncologist

MSc Prostate Cancer

Sheffield Hallam University, UK

Director of Men's Health Foundation Ghana

Tel: 0541090045

E. mail:[email protected]

Minority will expose the beneficial owners of SML, recover funds paid to company...

Minority will expose the beneficial owners of SML, recover funds paid to company...

Prof. Opoku-Agyemang has ‘decapitated’ the NPP’s strategies; don’t take them ser...

Prof. Opoku-Agyemang has ‘decapitated’ the NPP’s strategies; don’t take them ser...

Abubakar Tahiru: Ghanaian environmental activist sets world record by hugging 1,...

Abubakar Tahiru: Ghanaian environmental activist sets world record by hugging 1,...

Prof. Naana Opoku-Agyemang will serve you with dignity, courage, and integrity a...

Prof. Naana Opoku-Agyemang will serve you with dignity, courage, and integrity a...

Rectify salary anomalies to reduce tension and possible strike action in public ...

Rectify salary anomalies to reduce tension and possible strike action in public ...

Stop all projects and fix ‘dumsor’ — Professor Charles Marfo to Akufo-Addo

Stop all projects and fix ‘dumsor’ — Professor Charles Marfo to Akufo-Addo

Blue and white painted schools will attract dirt shortly – Kofi Asare

Blue and white painted schools will attract dirt shortly – Kofi Asare

I endorse cost-sharing for free SHS, we should prioritise to know who can pay - ...

I endorse cost-sharing for free SHS, we should prioritise to know who can pay - ...

See the four arsonists who petrol-bombed Labone-based CMG

See the four arsonists who petrol-bombed Labone-based CMG

Mahama coming back because Akufo-Addo has failed, he hasn't performed more than ...

Mahama coming back because Akufo-Addo has failed, he hasn't performed more than ...