In October 2003, while the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) approved the continued use of atrazine, the European Union (EU) announced a ban of atrazine because of its ever-present and unpreventable water contamination. If there is a chemical that has been successful at attaining widespread adoption in the phase of continuous criticism and sanctions, perhaps atrazine will be ranked among the top 5. Although banned in the EU since 2005, atrazine remains one of the most widely used herbicide across our country, particularly for growing maize.

After research had seen evidence that atrazine results in chemical castration (demasculinization) and in some instances feminizes exposed animals, concerns have been raised about the social and environmental sustainability of the people who use the chemical and their environment. It is a well known fact that amphibians are on the decline throughout the world. If common chemical pollutants, like atrazine, can depress the libido and behaviour of males in the wild as it has been reported from some laboratory experiments then it could pose a risk to the survival of wild populations. It is fair to investigate the effect of the chemical on the many farmers and communities in our maize growing belt that have been exposed to atrazine.

The Good of Atrazine

Since its development in 1958 as herbicide, atrazine has become one of the most widely used maize herbicides in almost all maize producing countries. It is the most commonly used herbicide in the world, and it is used in about 80 countries worldwide. In the US alone, it is estimated that over 35 million kilograms of atrazine are applied each year. Its relatively low cost and ability to kill broadleaf weeds without harming the maize plants have made it popular with farmers for decades.

In recent times, the scope of use of atrazine in many developing countries has broadened and it has been described as a selective systemic herbicide for pre- and post-emergent control of annual grass and broad leaved weed in maize, sorghum, fruits, orchards, sugar cane, pineapples, guavas, coffee, oil palm, roses, and forestry. Atrazine is used to stop pre- and post-emergence broadleaf and grassy weeds in major crops. The compound is both effective and inexpensive, and thus has been well-suited to production systems with very narrow profit margins, as is often the case with maize production in Ghana and many countries.

It is often claimed that atrazine is of great economic benefit to maize farmers. Some cost-benefit studies have assumed that atrazine boosts maize yields by 1%-6% average yield increase. Some farmers say that it saves them about GH¢5-10 per acre. Other farmers say that its ability to increase yields is critical as demand for food and alternative fuel increases. Support for these claims has however been limited. Cost-benefit analyses of atrazine indicate that its use is not justified economically. Such reported marginal yield increase does also not seem to warrant large-scale exposure of humans and the environment to this potentially hazardous chemical.

Atrazine and Sustainable Agriculture

Regrettably, atrazine is also one of the most commonly detected pesticides in ground and surface water in places where it is widely used. This concerns sustainable agriculture experts because atrazine has been linked to several kinds of health problems in humans and amphibians. It is phytotoxic to most vegetables, potatoes, soya beans, and groundnuts. It is alleged that it has endocrine disruptor effects, possible carcinogenic effect and an epidemiological connection to low sperm levels in men. As a result of these concerns, the use of this chemical has been restricted in conventional agriculture in many countries while it has been banned in sustainable agriculture.

Deficient in ways to estimate the expected value of harm, sustainable agriculture has taken the precautionary decision to ban atrazine, which also reflect society's judgments about the risks associated with worst-case outcomes. Also, if atrazine were banned the opportunity costs to the farmer could be surprisingly small.

Sustainable Agriculture in Ghana questioned?

It appears that our 'grow more food' campaign recently launched as part of the 26th Farmer's Day Celebration in Ghana has been largely successful. Our successes could be attributed to a long list of reasons most of which questions the sustainability of our approach and strategy. It therefore stands reason to interrogate our agricultural policy and to question the continuous use of unsustainable inputs and practices that have negative effects on our environment and our highly valued ecosystems.

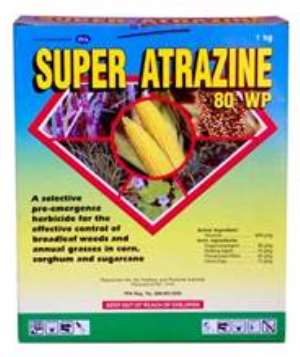

Sustainable agriculture banned Atrazine in 2005 and offered alternative pesticides in its place. However, the chemical is widely used in Ghana on maize, pineapple and orchard plots. Alternatives to these pesticides exist but the country has not yet made the switch to new types of agriculture production. In Ghana, the promotion of the chemical has received a major boost. Atrazine appears in the market under many trade names, often with the intent to outwit and to confuse unsuspecting farmers who try to avoid the use of the chemical. Input dealers have been very aggressive with the campaign to reach every corner of the country and every crop. Our unregulated and sometimes unprofessional advertising industry has also enhanced and facilitated promotions of these dealers with messages that are sometimes crafted to mislead, coerce and catch the attention of producers to incorrectly apply such chemicals. This makes it easy for input dealers to sell their chemicals. Farmers are led to accept fake packages and misleading marketing messages, not because of facts, but because they trust messages from people with a familiar face. As a result, many farmers in Ghana today are abandoning tried and tested sustainable practices for short term solutions that atrazine and other chemicals offer.

Sustainable agriculture banned Atrazine in 2005 and offered alternative pesticides in its place. However, the chemical is widely used in Ghana on maize, pineapple and orchard plots. Alternatives to these pesticides exist but the country has not yet made the switch to new types of agriculture production. In Ghana, the promotion of the chemical has received a major boost. Atrazine appears in the market under many trade names, often with the intent to outwit and to confuse unsuspecting farmers who try to avoid the use of the chemical. Input dealers have been very aggressive with the campaign to reach every corner of the country and every crop. Our unregulated and sometimes unprofessional advertising industry has also enhanced and facilitated promotions of these dealers with messages that are sometimes crafted to mislead, coerce and catch the attention of producers to incorrectly apply such chemicals. This makes it easy for input dealers to sell their chemicals. Farmers are led to accept fake packages and misleading marketing messages, not because of facts, but because they trust messages from people with a familiar face. As a result, many farmers in Ghana today are abandoning tried and tested sustainable practices for short term solutions that atrazine and other chemicals offer.

Atrazine is designed to kill

The harm that atrazine and other herbicides cause is not accidental. It is designed to kill living organisms and is therefore very often harmful to humans and other species, as well as the targeted pests. Like other triazine herbicides, atrazine functions by binding to the plastoquinone-binding protein in photosystem II, which animals' lack. Plant death results from starvation and oxidative damage caused by breakdown in the electron transport process. Oxidative damage is accelerated at high light intensity.

Ban Atrazine in Ghana

Maize growers fear that a ban action could undermine yields. For most farmers banning atrazine or using other, less effective herbicides, would mean sacrificing today's yields, which are already too low to secure them a sustainable livelihood and an efficient production system.

Such fear does not appear to have a place in a scientific and technological age like ours. In fact there are many viable ways of producing maize without relying on a controversial chemical. This has been demonstrated in European countries such as Germany and Italy, which both banned atrazine in 1991. Since the ban, it has been well documented that maize yields and acres of maize harvested in Italy and Germany have risen, not declined. This is a good indication that atrazine use is not as fundamental to crop production as the manufacturer would like the public and selling countries to believe.

Alternatives and Sustainable Agriculture?

Sygenta, the primary maker of atrazine, claims there are no viable alternatives to their best-selling herbicide. However, it has successfully produced an alternative herbicide that does about the same amount for maize yields as atrazine but which is more environmentally friendly than atrazine.

Farmers are not enemies of nature. They understand that a healthy ecosystem supports their production through environmental services such as pest control, pollination and soil fertility. But they do not always have the knowledge, technology or support to farm in the most efficient way for nature; and as a result they may make inappropriate choices for the long-term health of their farms and communities. Sustainable Agriculture is bringing signals from the market that farmers need to make changes and crucially it is also bringing training and technical assistance in how to make those changes.

Certified organic crop farmers have been proving for years that weed control is possible without chemicals. That doesn't mean that one has to be completely organic to be atrazine-free. However, it has become quite clear in recent times that certain best management practices, including organic and sustainable cropping strategies, can help remove herbicides like atrazine from conventional farm fields. Here are a few demonstrated strategies:

- Long crop rotations that consist of soybeans, forages and small grains can break up weed cycles quite effectively.

- Farmers have found that planting cover crops that have low market value after harvest of the main crop or even before planting can suppress weeds, as well as reduce erosion and enrich the soil.

- Mechanical weed control methods such as use of rotary hoes, cultivators and others can be effective tools particularly on land that is not highly erosive.

- Mixed cropping can reduce reliance on herbicide even more.

Sustainable agriculture is not just about organic growing. It is a whole chain of production systems that work, but the policy deficit has unfortunately undermined a production method that has been proven to be ecologically and socially friendly, and capable of ensuring food security.

What the EPA can do

As a developing country, we have less capacity to undertake thorough investigations into our ecosystems. We also have limited capacity to interrogate the industry that produces the chemical to provide data to actually prove that the chemical is harmful. Our approach to atrazine use must be similar to the European Union: to regulate the chemical. The EPA has to operate under the precautionary principle, which says that if there is the potential for a chemical to cause environmental and public health harm, then that chemical should be banned. In the case of Atrazine, it is better to ban it, because it is ubiquitous in our waters.

Conventional Agriculture can still act...

While we continue to procrastinate on a ban, the problems associated with atrazine will continue to send scientists, farmers and agronomists in search of ways to keep the herbicide from becoming a water pollutant. In many places, the majority of atrazine that leaves crop fields is known to be lost through water run-off, particularly after heavy rains. The remainder of lost atrazine is caused by soil erosion. Our conventional farmers would do us a great service to observe the following best practices to reduce atrazine applications and keep it from becoming a pollutant in our environment:

- Do not apply when heavy precipitation is in the forecast.

- Do not apply atrazine within 20 meters of any well or sinkhole.

- Do not apply atrazine within 60 meters of a lake, reservoir or pond. Mix chemical and fill and rinse your sprayer at least 60 meters from any well, stream, river, lake, reservoir or pond.

- Plant a 20-meter buffer of vegetation along streams or rivers.

- Incorporate atrazine into the soil using mechanical tillage equipment.

- Utilize high-residue farming methods to reduce soil erosion, and thus atrazine runoff.

There are also numerous ways to reduce atrazine applications while maintaining maize yields. The following are examples that could help transition from the use of atrazine:

- Use integrated pest management (IPM) to scout for weeds. This makes it possible to match spraying to weed infestations rather than applying chemicals to an entire field indiscriminately.

- Use less than what the label recommends.

- Applying atrazine after maize has emerged, rather than before, can reduce runoff by as much as 50%.

- Applying atrazine in a narrow band in crop rows can reduce the amount of herbicide needed.

- Rotating crops can reduce atrazine use by at least half.

A ban is imminent...

As a country, we must follow the path of sustainable agriculture in as far as use of atrazine and other similar herbicides like paraquat are concerned. We have to take the precautionary decisions, which also reflect our society's judgments about the risks associated with the worst-case outcomes of the continuous use of the chemicals. We have to consider how expensive it would be if the use of Atrazine were continued for many years. We have to think about the environmental and public health harm that atrazine causes and take the precaution to ban its use in our farming system.

There are many ways that sustainable farming is benefiting farmers and communities. There has been tremendous improvement in productivity and income for farmers who have adopted best management practices. These farmers have improved their productivity by applying the principles of Integrated Pest Management (IPM) to reduce pests and to apply fertilisers responsibly to improve on soil nutrients and to enhance the biodiversity in their farms. It is known that increased investment in natural resources management and rural development is critical to reducing poverty, improving food security and enhancing biodiversity conservation. As the "people, planet and prosperity" message spreads through the marketplace, demand for goods from sustainable farms is also growing. We can run away from the reality today, but the trend to responsible sourcing will catch with us up sooner than we expect. We cannot run away from the power of the market to change behaviour. Let us ban atrazine now before it bans us from our waters and from the rich diversity of nature in our country.

There are many ways that sustainable farming is benefiting farmers and communities. There has been tremendous improvement in productivity and income for farmers who have adopted best management practices. These farmers have improved their productivity by applying the principles of Integrated Pest Management (IPM) to reduce pests and to apply fertilisers responsibly to improve on soil nutrients and to enhance the biodiversity in their farms. It is known that increased investment in natural resources management and rural development is critical to reducing poverty, improving food security and enhancing biodiversity conservation. As the "people, planet and prosperity" message spreads through the marketplace, demand for goods from sustainable farms is also growing. We can run away from the reality today, but the trend to responsible sourcing will catch with us up sooner than we expect. We cannot run away from the power of the market to change behaviour. Let us ban atrazine now before it bans us from our waters and from the rich diversity of nature in our country.

Christian D. B. Mensah

Sustainable Agriculture Expert

Agro Eco-Louis Bolk Institute

Critics fear Togo reforms leave little room for change in election

Critics fear Togo reforms leave little room for change in election

Flooding: Obey weather warnings – NADMO to general public

Flooding: Obey weather warnings – NADMO to general public

Fire in NDC over boycott of Ejisu by-election

Fire in NDC over boycott of Ejisu by-election

NDC to outdoor Prof Jane Naana Opoku-Agyemang as running mate today

NDC to outdoor Prof Jane Naana Opoku-Agyemang as running mate today

Ejisu: CPP seeks injunction to stop April 30 by-election

Ejisu: CPP seeks injunction to stop April 30 by-election

Dismiss ECG, GWCL, GACL bosses over losses – United Voices for Change tells gov’...

Dismiss ECG, GWCL, GACL bosses over losses – United Voices for Change tells gov’...

Submit 2023 audited financial statements by May – Akufo-Addo order SOEs

Submit 2023 audited financial statements by May – Akufo-Addo order SOEs

Current power outages purely due to mismanagement – Minority

Current power outages purely due to mismanagement – Minority

ECG hoists red flag to fight Ashanti Regional Minister over arrest of General Ma...

ECG hoists red flag to fight Ashanti Regional Minister over arrest of General Ma...

Mahama’s 24hr economy will help stabilise the cedi; it’s the best sellable polic...

Mahama’s 24hr economy will help stabilise the cedi; it’s the best sellable polic...