The cancellation notice of the auction of Queen-Mother Idia mask on 4 December by Sotheby's could not have been shorter:

“The Benin Ivory Pendant Mask and other items consigned by the descendants of Lionel Galway which Sotheby's had announced for auction in February 2011 have been withdrawn from sale at the request of the consignors (2).

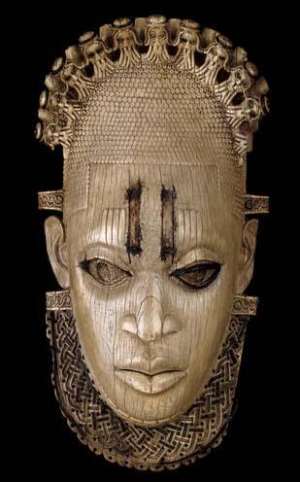

This short notice is a great contrast to the enthusiastic announcement of the proposed auction where the excellent artistry of the hip mask was underlined. “All of the ivory masks are widely recognized for the quality of their craftsmanship, for the enormous scale of Benin's artistic achievement and for their importance in the field of African art “.

But what more does the cancellation tell us? Very little except that the proposed auction will not take place as announced. Will the auction take place sometime in the future and somewhere else other than at Sotheby's? Will the mask be silently passed on to one of the so-called “universal museums” without our knowing?

It is stated that the Benin objects “have been withdrawn from sale at the request of the consignors” Did the “owners” withdraw because of the protests from Nigeria Liberty Forum and others, and hope to present them at a future date or have they arrived at the conclusion that it is wrong to sell the cultural property of others, especially in a case like this where the object has been acquired by an ancestor in a violent attack of the owners? Are they prepared to renounce their alleged rights to these blood artefacts? Did the consignors realize that the sale of such blood artefacts can only revive wounds that may still be felt by the successors of those killed in the process of invasion? Do the Galways intend to return the Queen-Idia mask and the other artefacts to the people of Benin or simply keep them out of public sight as they have done twice after exhibitions in 1947 - “Ancient Benin” and 1951 - “Traditional Sculpture from the Colonies” ?

Sotheby's and the Galways may have been amazed by the massive public outcry at the announcement of the proposed auction. The timing of the proposed auction may have been arbitrarily chosen but it is noteworthy that a week or so before, Sotheby's had auctioned an African artefact, a Luba female caryatid stool, for $7.1 million without any problem. This may have encouraged them to think it was the right time to make a huge profit on African artefacts. The history of that piece is different from that of the Benin pieces that are heavily charged with sentiments and emotions. Moreover, the Queen-Mother Idia hip mask has become a Pan-African symbol and thus invested with a symbolism and significance that extend far beyond the boundaries of Benin and Nigeria.

But Sotheby's and the Galway successors need not have been surprised since protest at the possession of Benin Bronzes by Western museums and private collections has a long history.

Various Nigerian governments and parliaments have called for the return of these objects. When a museum was to be opened in Benin City, Ekpo Eyo, on behalf of Nigeria made several requests to all the museums holding Benin objects to return a few of them. Not a single object was returned and the museum was opened with photographs of some of the Benin Bronzes:

“By the end of the 1960s, the price of Benin works had soared so high that the Federal Government of Nigeria was in no mood to contemplate buying them.

When, therefore a National Museum was planned for Benin City in 1968, we were faced with the problem of finding exhibits that would be shown to reflect the position that Benin holds in the world of art history. A few unimportant objects which were kept in the old local authority museum in Benin were transferred to the new museum and a few more objects were brought in from Lagos. Still the museum was “empty”. We tried using casts and photographs to fill gaps but the desired effect was unachievable. We therefore thought of making an appeal to the world for loans or return of some works so that Benin might also be to show its own works at least to its own people. We tabled a draft resolution at the General Assembly of the International Council of Museums (ICOM) which met in France in 1968, appealing for donations of one or two pieces from those museums which have large stocks of Benin works. The resolution was modified to make it read like a general appeal for restitution or return and then adopted.

When we returned to Nigeria, we circulated the adopted resolution to the embassies and high commissions of countries we know to have large Benin holdings but up till now we have received no reaction from any quarters and the Benin Museum stays “empty”. (3)

In 2000 the Benin Royal Family sent a petition to the British Parliament for the restitution of the Benin artefacts (4)

In addition to protests from Benin Royal Family over the ages, the late Bernie Grant, Member of the British Parliament and Chair of the African Reparations Movement (UK), regularly protested against the continued illegal detention of the Benin Bronzes. (5)

During the 2007 travelling exhibition, - BENIN - KINGS AND RITUALS, COURT ARTS FROM NIGERIA, the present Oba, His Majesty Oba Erediauwa of Benin, great grandson of Oba Ovonramwen, in whose reign the Benin bronzes were looted by the British in 1897, made again in the foreword to the catalogue of the exhibition a plea for the return of some of the Benin Bronzes: “We are pleased to participate in this exhibition. It links us, nostalgically, with our past. As you put this past on show today, it is our prayer that the people and government of Austria will show humaneness and magnanimity and return to us some of these objects which found their way to your country”. (6) Few pages later in the same catalogue, followed the response of four museum directors of Western countries in a preface which in its eurocentricism, arrogance, immorality and cynicism is only surpassed perhaps by the infamous Declaration on the Value and Importance of Universal Museums. (2002.(7) They rejected the demand for return of the Benin Bronzes and advised that the Nigerian should forget the past and look onto the future.

Again in 2007, Professor Tunde Babawale, Director of the CBACC, Lagos, wrote to Neil MacGregor, Director of the British Museum, stating that

“The essence of this letter is to request that the British Museum, safely return/hand over the original 16th century Ivory Mask which was last worn by King Ovoramwen Nogbasi of the ancient Benin Empire before he was exiled by Britain.

The Ivory Mask is the official Emblem for FESTAC AND A UNIFICATION SYMBOL FOR Nigerians and Black people worldwide. The mask is also of great significance to us as Africans.”

MacGregor's reply to Babawale does not address the main issue of the return of the mask which was said to be the essence of his letter. Instead, he writes:

“Let me assure you that the British Museum appreciates the significance of the Benin material in the collections for Nigeria, Africa and the world, and wishes to make it better understood and more accessible in Africa and worldwide. To this end, we are currently engaged in a new dialogue with the National Commission on Museums and Monuments in Nigeria”.

Both letters of Babawale and MacGregor are reproduced in Annex V below. It is remarkable that the British Museum denies to Nigeria and Africa the stolen/looted Benin mask in order “to make it better understood and made accessible in Africa and worldwide.” The reader must judge for himself or herself the value of such reasoning which flies in the face of truth and common sense,

In 2008, a formal request was sent on behalf of the Benin Royal Family to the Art Institute of Chicago and the Field Museum, Chicago for the return of some of the Benin Bronzes but to no avail. Not even a letter of acknowledgement was sent by the venerable institutions to the Benin Royal Family. There are people who praise the artistry of Benin but do not even feel obliged to extend the most elementary courtesy to the Benin Monarchy the presence of which generated the looted artefacts they are detaining.

The United Nations, UNESCO and ICOM (International Council of Museums) as well as several international conferences have urged the holders of artefacts such as the Benin Bronzes to return some to their countries of origin but with no success.

It is thus clear that there is a long history of protest and opposition to the holding of “blood artefacts” which were obtained at the cost of loss of several lives. Sotheby's and the consignors could therefore not have been totally surprised at the protest. However, they might have been overwhelmed by the extent of the world-wide protests. Westerners have been misled by many false prophets proclaiming the right and duty of the West to hold on to the blood artefacts. This has led to turning a deaf ear to requests for restitution and to non-consideration of such demands. This has removed any moral inhibitions people may have had with respect to dealing with looted/stolen artefacts of others. But times have changed and so must potential sellers and auction houses also change.

The wind is now blowing in favour of restitution. France has recently restored Korean manuscripts looted in 1866; Yale University has returned Peruvian artefacts than had been in the USA since 1912; and Egypt has recovered over the last decade some 5000 artefacts wrongfully taken from the country. Several American museums and universities have returned looted artefacts to Italy. The Brooklyn Museum is about to return some 4,500 pre-Columbian artifacts taken from Costa Rica a century ago even though Costa Rica has not asked for them and the possession by the museum appears to be legal. China, Egypt, Greece, Peru, Nigeria and other States have established a conference to press for cases of restitution and submitted lists of objects to be returned to their countries of origin. Henceforth, all are aware of the demand of certain countries for the return of their looted artefacts and one cannot continue to argue, as some in Western capitals are wont to, that there have been no requests for restitution.

The way forward to resolving cultural property disputes, as we have continued to argue, is to recognize that there is something wrong in the present situation where the Ethnology Museum of Berlin, or the British Museum or the Ethnology Museum, Vienna have more Benin Bronzes than Benin itself. Berlin, for example has 580 Benin artefacts. What are the Germans doing with so many Benin artefacts when the Benin people (Edo) have pleading in vain for years to get some of them back?

Recognition of the present imbalance in possessions of African cultural objects should lead to negotiations for returning some of them. We should, in principle, proceed first by dialogue and failing that, judicial process. However, Western museums and their governments have not shown themselves to be very keen on dialogue, despite all pretence to the contrary. Indeed, leading museum directors in London, Chicago, New York and Vienna have shown reluctance to discuss and resentment at the very mention of the idea of discussing restitution of looted cultural artefacts. Those calling for their return are considered unreasonable but not those refusing to discuss even the possibility of restitution. It seems to me that it is the lack of pressure to bear on Western museums and their governments that allows them to get away with arguments and defences that no student would dare to present to professors without the risk of being thrown out of the university.

Instead of seeking ways to accommodate the demands of Africans for the return of their artefacts, leading Western museum directors have been busy inventing theories and stories which end up by supporting their retention of looted African artefacts. They argue that our looted artefacts belong to the heritage of human kind and thus their location in Western museums is justifiable in the interest of humankind. But the “universalism” preached by the Westerners is a “European Universalism” as opposed to true “universal Universalism” which would include all humankind and work against the domination of one group by another. Western museum directors and their supporters have shown that they are not yet ready for such a world: they have hijacked the cultural artefacts of others and refuse to return any. Hence we have situations such as the proposed sale by successors of some of those who invaded Benin in 1897, killing many women and children, deposing the king, Oba Ovonramwen and setting Benin City on fire, just as they had done in Asante (Ghana) in 1874. Similar actions had also been carried on in Magdala, (Ethiopia) and in Beijing, (China). None of those involved in such actions seems to have any bad conscience. Indeed, they think they are doing us a great favour by keeping our artefacts with them. Unfortunately, some Africans who should know better seem to buy this dishonest argument.

But in all the discussions on the abortive auction of the Queen-Mother Idia mask as well as in the restitution debates, one major actor is conspicuously absent or ignored by some participants, namely, the British Government. There is no doubt that the main responsibility for the invasion of Benin, the looting of the Benin Bronzes and the burning of Benin City lie with the British Government which planned, financed, organized and implemented the invasion. Indeed, the British Government has not sought to deny its responsibility; what it has tried to do directly or through interposed agents, is to offer justifications for the invasion and looting, none of which is convincing. The most absurd explanation for the looting and selling of the Benin Bronzes has been that the British needed to finance the costs of the invasion and to provide for widows and children of the notorious punitive expedition. One commits an outrageous crime and defends that action by the need to finance that action and to assist those carrying out the action for damages they may have received in carrying out the action.

Another ploy of the British Government has been to divert all claims for restitution of looted objects to the British Museum which it turn declares its inability to respond positively to demands for restitution because of a governing parliamentary act. Demands for restitution should de directed in the first place to the British Government which is primarily responsible for the initial looting and to the British Museum for handling goods it knows or ought to have known were looted and illegally transferred from the country of origin.

The British Parliament has passed a law, Holocaust (Return of Cultural Objects)

Act 2009 (8) that enables owners of Nazi looted artworks now in public British museums and galleries not only to obtain compensation for the loss but to receive the looted object. Some have wondered whether this act would not be sufficient for recovering the Benin bronzes... It is suggested that the loss of the Benin bronzes could be compared to loss due to Nazi actions. I do not want to enter into comparisons here for injustice is injustice and both situations show humankind at its lowest level. However, we should recall that in one case, the offenders were German official whereas in the second case, the perpetrators were British. A British government is not very likely to pass a law that would enable recovery actions in situations where the Government itself had planned and executed the notorious actions in question. But even more important, the act makes it very clear that it only applies to actions relating to Nazi seizures within a specific period. Article 3 of the Act defines Nazi era thus: “Nazi era” means the period—(a) Beginning with 1 January 1933, and (b) Ending with 31 December 1945. “

Therefore the canons of judicial interpretation would not permit the extension of the Holocaust Act to looting by British soldiers in Benin in 1897. Indeed, the fear of claims by Benin and by Greece was a point which had to be clarified during debates preceding the passing of the act. A different law would have to be made. We should caution over confidence in the judicial system helping to solve issues arising from the loot of 1897. The matter should be dealt with in other arenas.

An entity that was also conspicuously silent and absent in the discussions on the projected auction of the Queen-Mother Idia mask was the Nigerian Government. Most people, especially, young Nigerians, had sought in vain for indications of the policy of their government on this and related issues. Fortunately, a group of young Nigerians took the initiative to start actions that led to the eventual cancellation of the proposed auction. We have now received reports of statements by the Nigerian government.

According to reports to the Nigerian Tribune, “the Federal Government is seeking diplomatic option to end the controversy surrounding the reported planned sale of the prized art objects.”(9) The Tribune reports further that “The source disclosed that President Jonathan had given instructions to the effect that no effort should be spared to get the Benin arts, as well as other such artefacts that symbolised the pride of Nigerians and their rich cultural heritage.

The president also ordered that machinery should be set in motion to get the artefacts repatriated into the country.

On the nature of the president's intervention, the source said appropriate officials that would handle the matter had been contacted and were expected to take the matter to the highest level of authority in Britain, adding that “we are ready to pursue the matter to the highest level.”

We have no detailed explanation about the “diplomatic option” that the Nigerian Government is said to be seeking. However, if this is the same as the so-called “quiet diplomacy” which Nigerian authorities have been pursuing in the last 50 years or so without any tangible results, then one may be sceptical. We would rather have an open and loud diplomacy in which the general public is well informed at every step about what is happening. We do not recommend an approach that keeps everything secret and when you inquire about progress you are told that diplomacy takes time or that one cannot, for diplomatic reasons, reveal anything. At the end one will be informed about the negative response based on one of the lame excuses in the arsenal of the British such as the Government cannot intervene in a matter of private law or that one should address oneself directly to the British Museum.

Nigerian authorities may wish to look at the position and methods of another African country which, unlike Nigeria, has been extremely successful in obtaining the return of its looted/stolen artefacts. Egypt, under the leadership of Zahi Hawass, has been able to secure the return of more than 5000 looted/stolen Egyptian artefacts from Western museum. The methods employed by Hawass are the opposite of “quiet diplomacy”. He lets the general public know what Egypt wants and reports on his homepage the responses of the museum to his requests. He gets the Egyptian public and the world at large to see and realize what is going on. He treats public matters publicly and so there is no doubt who is doing or not doing what. The transparency often proclaimed but hardly practised is seen here at work. Writing about the success of Peru in getting back thousands of its objects from the University of Yale in the USA, Hawass states “One of the key components in my campaign to return stolen artifacts to Egypt is the media. I have been insistent on bringing this unacceptable behavior to light through press releases, print media and television appearances.”(10)

We are encouraged to read that “The president also ordered that machinery should be set in motion to get the artefacts repatriated into the country.”

This new body should recommend sending a team from Nigeria to establish a list of looted/stolen Nigerian artefacts, including the Benin Bronzes, in Western museums. We have provided (Annex I) here a list of such institutions that could be used as a starting point. If the Government does not already have such a list. The experience of the Chinese government could be extremely useful. The aim of the visit of Chinese museum experts to Western museums was “to build a complete database of the Old Summer Palace's lost relics so we can have a clearer view of the historical royal garden...before it was looted and burned down in 1860 by invading British and French armies. We have clarified that this is an attempt to document rather than to seek a return of those relics, even though we do hope some previously unknown relics might surface and some might be returned to our country during our tracing effort.” (11)

Maybe the Nigerian authorities are not aware that regarding the restitution of the Benin Bronzes and other Nigerian artefacts, there is great support for Nigeria in this matter. Apart from Museum officials and those who have built their careers on blood artefacts, most Westerners are in favour of the restitution of the bonzes. Many are of course not aware of the existence of these objects in their towns and countries but once properly briefed, they are shocked that their governments could tolerate such a scandalous situation that deprives Africans of their cultural artefacts which have no role in European culture. But this support and sympathy have to be cultivated, canalized and utilized effectively. This implies contact with the public in all these through the media, e.g. press releases, adverts and articles. We are yet to see a Nigerian diplomat or official presenting Nigeria's views and position on this matter in Western media. Could Nigerian embassies that have public relations and public information sections not assist in this matter? Above all, there should be a definite place in the internet where the public could look for information on Nigeria's policies.

The abortive auction of the Queen-Mother Idia mask offers opportunity to Nigeria to make up for lost time and opportunities. Following are a few points that come to my mind:

- Issue a detailed Government policy on this case and on restitution generally;

- Create a website where all such issues can be discussed and government's policy explained;

- Name one person or body that speaks for Nigeria on restitution and related matters;

- Request Nigerian diplomats to attend exhibitions on Nigerian culture and related matters that are held at their duty stations;

- Publish and publicize Nigeria's activities on restitution and related issues;

- Review relevant Nigerian laws on cultural artefacts, their preservation and offences related thereto.

Nigeria, in alliance with Egypt, Ethiopia, Ghana, Greece, Italy, Peru as well as other States with interest in restitution matters must bring enough pressure on Western States so that it is finally accepted by all that stealing and looting the cultural property of others is against the fundamental principles of international co-operation as enshrined in the principles of the United Nations and UNESCO;

The moral principle and commandment that “Thou shalt not steal” must be accepted as extending to all objects and property.

Nigeria must finally indicate to the rest of the world that it intends to preserve and keep its cultural artefacts for future generations who will not need to go to London, Paris, Berlin, New York, Chicago and other Western cities in order to see what their forefathers have achieved in this area. Nigeria has a lot to be proud of but unless serious measures are taken, to discourage plundering and to recover the looted objects future generations will have very little to see and will curse earlier generations.

Kwame Opoku 1 January, 2011

NOTES

1. Museum, Vol. XXL, no 1, 1979, Return and Restitution of cultural

Property, pp. 18-21, at p.2, Nigeria. See also http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Nh2Tac1gNPU&feature=share http://www.modernghana.com/news/241980/1/youtube-crown-fraud-stolen-benin-bronzes-british-m.html http://www.youtube.com

2. Sotheby's http://investor.shareholder.com

The Independent, http://www.independent.co.uk

3. Museum, Vol. XXL, no 1, 1979, at p.21, Nigeria. See Annex I for list of the holders of the Benin Bronzes.

4. Annex II,

5. Annex III.

6. Barbara Plankensteiner (Ed), Benin Kings and Rituals: Court Arts from Nigeria, Snoeck, 2007.

7. Declaration on the Value and Importance of Universal Museums. (2002). http://www.clevelandart.org/museum/info/CMA206_Mar7_03.pdf The Declaration was signed in December 2002 by 18 major museums that declared their intention not to return the cultural artefacts from Greece ,African and Asian States that have been in Western museum over a long period.

K.Opoku, “Is the Declaration on the value and Importance of the“universal museums” now worthless? Comments on imperialist Museology. http://www.modernghana.com

8. Readers may wish to consult a very useful note on the Holocaust Restitution Bill by Philip Ward. http://www.parliament.uk/briefingpapers/commons/lib/research/briefings/snha-05090.pdf

The Art Newspaper wrote:

“The government's major concern about Mr Dismore's Private Members' Bill is that amendments may be put to extend its scope. In particular, it will inevitably be seized upon by parliamentarians who are campaigning for the return of the Parthenon Marbles to Athens. Similar moves might be made by those calling for the return of the Benin Bronzes to Nigeria, the Rosetta Stone to Egypt or the Lewis Chessmen to Scotland. The DCMS is therefore expected to press for a clear wording that would preclude deaccessioning being extended beyond the 1933-45 period.”

UK parliament closer to passing bill allowing museums to deaccession Nazi-looted art Legislation expected to be limited to 1933-1945 only

http://www.theartnewspaper

Andrew Dismore, the Labour MP for Hendon who introduced the Bill stated during debate in the Second Reading of the Holocaust (Stolen Art) Restitution Bill:

“Above all, the Bill is strictly limited as to time, place and perpetrator of the original deprivation of the object from its lawful owner. It is not a Trojan horse for the Parthenon sculptures—that is my next Bill—or for any other artworks or cultural items. It is a discreet, modest measure, limited in scope and time to rectify decades of injustice, and I commend it to the House.” http://services.parliament.un

See also, Elginism “Nazi looted artefacts in the UK can now return home “ http://www.elginism.com

K. Opoku, “Will Britain join other Nations in Returning Stolen/Looted Artworks to rhe Rightful Owners?”

http://www.modernghana.com

“Holocaust (Return of Cultural Objects) Act 2009” http://www.lootedart.com

9. Nigerian Tribune, http://tribune.com.ng

10. “Peru succeeds in getting 4,000 objects back home!” http://www.drhawass.com

Kwame Opoku,” Egyptian Season of Artefacts Returns: Hopeful Sign to be followed by Others? http://www.elginism.com

11. China to Research Foreign Museum Archives for Chinese Artifacts http://illicit-cultural-property, http://www.artsjournal.com

Elginism,”British Museum holds highest number of looted Chinese relics,” http://www.elginism.com

Elginism,”China wants to catalogue its artefacts in Museums abroad.” http://www.elginism.com

Elginism.” China's worldwide hunt for artefacts looted from Beijing's Summer Palace”, http://www.elginism.com

K. Opoku, “Chinese Research Artefacts Looted in Anglo-French Attack on the Summer Palace in 1860”, http://www.modernghana.com

K. Opoku, “Is it not time to fulfil Victor Hugo's wish? Comments on Chinese Claim to Looted Artefacts on Sale at Christie's”, http://www.modernghana.com

ANNEXES

These historic documents which are also found in Peju Layiwola, Benin 1897.com, Art and the Restitution Question, 2010,( Wy Art Editions, P.O. Box 19324, University Post Office, Ibadan, Oyo State, Nigeria. www.benin 1897.com ) enable the reader to follow closely the reasoning behind the positions of the parties involved in the debate on the restitution of the Benin Bronzes.

ANNEX I

LIST OF HOLDERS OF THE BENIN BRONZES

Almost every Western museum has some Benin objects. Here is a short list of where the Benin Bronzes are to be found and their numbers. Various catalogues of exhibitions on Benin art or African art also list the private collections of the Benin Bronzes. The museums refuse to inform the public about the number of Benin artefacts they have and do not display permanently the Benin artefacts in their possession since they do not have enough space. Some museums have their section on Benin or African artefacts closed for years for repair works or other reason.

Berlin – Ethnologisches Museum 580.

Chicago – Art Institute of Chicago 20, Field Museum 400.

Cologne – Rautenstrauch-Joest-Museum 73.

Glasgow _ Kelvingrove and St, Mungo's Museum of Religious Life 22

Hamburg – Museum für Völkerkunde, Museum fur Kunst und Gewerbe 196.

Dresden – Staatliches Museum für Völkerkunde 182.

Leipzig – Museum für Völkerkunde 87.

Leiden – Rijksmuseum voor Volkenkunde 98.

London – British Museum 900.

New York – Metropolitan Museum of Fine Art 163.

Oxford – Pitt-Rivers Museum/ Pitt-Rivers country residence, Rushmore in Farnham/Dorset 327.

Stuttgart – Linden Museum-Staatliches Museum für Völkerkunde 80.

Vienna – Museum für Völkerkunde 167.

ANNEX II

The Case of Benin

Memorandum submitted by Prince Edun Akenzua to the British Parliament

I am Edun Akenzua Enogie (Duke) of Obazuwa-Iko, brother of His Majesty, Omo, n'Oba n'Edo, Oba (King) Erediauwa of Benin, great grandson of His Majesty Omo n'Oba n'Edo, Oba Ovonramwen, in whose reign the cultural property was removed in 1897. I am also the Chairman of the Benin Centenary Committee established in 1996 to commemorate 100 years of Britain's invasion of Benin, the action which led to the removal of the cultural property.

HISTORY

“On 26 March 1892 the Deputy Commissioner and Vice-Consul, Benin District of the Oil River Protectorate, Captain H L Gallway, manoeuvred Obal Ovonramwen and his chiefs into agreeing to terms of a treaty with the British Government. That treaty, in all its implications, marked the beginning of the end of the independence of Benin not only on account of its theoretical claims, which bordered on the fictitious, but also in providing the British with the pretext, if not the legal basis, for subsequently holding the Oba accountable for his future actions.”

The text quoted above was taken from the paper presented at the Benin Centenary Lectures by Professor P A Igbafe of the Department of History, University of Benin on 17 February 1997.

Four years later in 1896 the British Acting Consul in the Niger-Delta, Captain James R Philip wrote a letter to the British Foreign Secretary, Lord Salisbury, requesting approval for his proposal to invade Benin and depose its King. As a post-script to the letter, Captain Philip wrote: “I would add that I have reason to hope that sufficient ivory would be found in the King's house to pay the expenses incurred in removing the King from his stool.”

These two extracts sum up succinctly the intention of the British, or, at least, of Captain Philip, to take over Benin and its natural and cultural wealth for the British.

British troops invaded Benin on 10 February1897. After a fierce battle, they captured the city, on February 18. Three days later, on 21 February precisely, they torched the city and burnt down practically every house. Pitching their tent on the Palace grounds, the soldiers gathered all the bronzes, ivory-works, carved tusks and oak chests that escaped the fire. Thus, some 3,000 pieces of cultural artwork were taken away from Benin. The bulk of it was taken from the burnt down Palace.

NUMBER OF ITEMS REMOVED

It is not possible for us to say exactly how many items were removed. They were not catalogued at inception. We are informed that the soldiers who looted the palace did the cataloguing. It is from their accounts and those of some European and American sources that we have come to know that the British carried away more than 3,000 pieces of Benin cultural property. They are now scattered in museums and galleries all over the world, especially in London, Scotland, Europe and the United States. A good number of them are in private hands.

WHAT THE WORKS MEAN TO THE PEOPLE OF BENIN

The works have been referred to as primitive art, or simply, artifacts of African origin. But Benin did not produce their works only for aesthetics or for galleries and museums. At the time Europeans were keeping their records in long-hand and in hieroglyphics, the people of Benin cast theirs in bronze, carved on ivory or wood. The Obas commissioned them when an important event took place which they wished to record. Some of them of course, were ornamental to adorn altars and places of worship. But many of them were actually reference points, the library or the archive. To illustrate this, one may cite an event which took place during the coronation of Oba Erediauwa in 1979. There was an argument as to where to place an item of the coronation paraphernalia. Fortunately a bronze-cast of a past Oba wearing the same regalia had escaped the eyes of the soldiers and so it is still with us. Reference was made to it and the matter was resolved. Taking away those items is taking away our records, or our Soul.

RELIEF SOUGHT

In view of the fore-going, the following reliefs are sought on behalf of the Oba and people of Benin who have been impoverished, materially and psychologically, by the wanton looting of their historically and cultural property.

(i) The official record of the property removed from the Palace of Benin in 1897 be made available to the owner, the Oba of Benin.

(ii) All the cultural property belonging to the Oba of Benin illegally taken away by the British in 1897 should be returned to the rightful owner, the Oba of Benin.

(iii) As an alternative, to (ii) above, the British should pay monetary compensation, based on the current market value, to the rightful owner, the Oba of Benin.

(iv) Britain, being the principal looters of the Benin Palace, should take full responsibility for retrieving the cultural property or the monetary compensation from all those to whom the British sold them.

March 2000

APPENDIX 21 http://www.publications.parliament.uk

ANNEX III

LETTER OF THE LATE BERNIE GRANT, MEMBER OF PARLIAMENT, TO DIRECTOR OF GLASGOW MUSEUM AND THE REPLY THERETO.

Mr Julian Spalding

Director

Art Gallery and Museum

Kelvingrove Glasgow

G3 6AG

10 December 1996

Dear Mr Spalding,

African Religious and Cultural Objects

Thank you very much indeed for your recent correspondence about the above matter.

I write on behalf of the Oba of Benin, Oma n'Oba, Uku Akpolokpolo, Oba Erediauwa, and on behalf of the Africa Reparations Movement (UK) of which I am the Chair. The subject of this letter is the Benin Bronzes, Ivories and other cultural and religious objects contained in the Glasgow Art Gallery and Museum, about which I understand you have recently spoken to Mr Edward Wood of the House of Commons Library.

As you are aware, most of the Benin religious and cultural objects currently in British museums and other institutions were looted in February 1897 from Benin City. The context of this was the battle for trade in the carve up of Africa, into "spheres of influence", by the European powers, and the launching of a military expedition by the British in 1897, to depose the King of Benin who insisted on preserving the independence and sovereignty of his kingdom.

The Benin religious and cultural objects belong to a living culture and have deep historic and social value, which go far beyond the aesthetic and monetary value which they hold in exile. I was recently informed by Prince Akenzua, the Oba's brother, who was in the UK on a quest to speak to MP's regarding the return of the Bronzes etc., that those officiating at the Oba's coronation ceremonies had forgotten the rituals. They had had to consult some of the Bronzes that are still in Benin, in order for them to wear the correct vestments and have the appropriate officials present.

Prince Akenzua explained that the previous coronation had been well over 50 years previously and because the ceremony is not written down, the officials had forgotten, and their only recourse to the proper rituals were the Bronzes which were made for that specific purpose. He went on to say that many of their ceremonies have not been performed satisfactorily because most of the Bronzes are missing. This situation is very distressing for the Benin people of today. Moreover, the objects have come to symbolise the intense sense of injustice widely felt in Africa, and indeed amongst many people of African origin in Britain, about the mis-appropriation of African art, cultural and religious objects, arising from the period of European colonisation.

There has for many years now, been a demand for these religious and cultural objects to be returned to Benin, and as the centenary of their looting approaches in February 1997, the strength of feeling around this has intensified. Formal requests for their return have been made in the past by the Nigerian Government, and by the Obas of Benin themselves, but have been met with refusal. A request for the mere loan of an ivory mask for the purposes of a major World African Arts Festival was denied in 1977, and this affair led to the cooling of relations between Britain and Nigeria at that time.

As Chair of the Africa Reparations Movement (UK), (ARM UK), at the recent meeting with Prince Akenzua, I discussed the plans for the centenary commemoration next year. The demand for the return of the Benin religious and cultural objects is clearly central to this occasion, and the Prince has formally authorised me to investigate the possibility of returning at least some of the objects at this time. However, as you will no doubt be aware, the legal position as regards returning artifacts lodged in English museums and institutions is complex, although a challenge to the current legislation features firmly on the agenda of ARM (UK). I understand though that the position in Scottish Law is different, and it is within the powers of individual local authorities to make decisions on the restitution of items from collections which they hold. I also understand that there are precedents for restitution where a formal request has been made.

The Royal Family of Benin has therefore authorised me to make such a formal request, and has asked me to draw an analogy with the recent return to Scotland of the Stone of Destiny. Just as the Stone is of such great significance to the people of Scotland, so the Benin treasures are signficant to the people of Benin. Theirs was a rich, sophisticated, and advanced civilisation, which was in many ways far more developed than contemporary European societies. The denial and destruction of the history of the Benin people were acts of appalling racism, which need urgently to be rectified. These are indeed some of the most distasteful and abiding injustices arising out of the period of European colonisation of Africa.

Whilst I am aware that the collection held in the Glasgow Art Gallery and Museum is a relatively minor one, its symbolic value is immense. The Oba himself would be more than pleased to visit Glasgow to receive the religious and cultural objects, and to express his appreciation if restitution can be arranged.

I would be grateful if you could look into this matter and let me have your views as soon as possible.

I remain,

Yours sincerely,

BERNIE GRANT M.P.

Art Gallery and Museum

Kelvingrove, Glasgow G3 BAG

Tel: 0141-287 2600 Fax: 0141-287 2608

Director of Glasgow Museums: Julian Spalding

Mr Bernie Grant MP

House of Commons

London SW1A OAA

10 January 1997

Dear Mr Grant

AFRICAN RELIGIOUS AND CULTURAL OBJECTS

We have now had a chance to consider your request for the return of the Benin bronzes, ivories and other cultural and religious objects contained in our collection. We have considered the whole complex position and have reached the following conclusion.

Though it is possible for our museum service to restitute items from its collection and we have done this recently in the case of some Aboriginal human remains, we cannot advise the City Council that this should happen in this case.

Our reasons are entirely professional. Museums have a collective responsibility, both nationally and internationally to preserve the past so that people can enjoy it and learn from it. In the case of the Benin collection in Glasgow though it is small and not of the highest quality, -it does play an important role in introducing our visitors to the culture, and religious beliefs of Benin, whose artistic achievements rank with the finest not just in Africa but in the whole world. Virtually all our 22 Benin items are on permanent view to the public in Kelvingrove and in St Mungo's Museum of Religious Life and their withdrawal from these displays would limit, in our opinion, our visitors' understanding of the world.

We have taken into account, too, the fact that the museums in Nigeria, including the one in Benin itself, do now have one of the world's finest representations of this great culture and our collections would not add significantly to this, even if the request for restitution had come from them. However, in this case, we are not considering a transfer from one public museum to another, but a request on behalf of the Oba of Benin, himself, for future religious use. We believe, however, that these artifacts have an important role to play in the public sector by informing over 3 million visitors here about the culture of Benin and, it has to be said, the history of British Imperialism.

Kind regards.

Juilan Spalding Director

cc Councillor F McAveety, Glasgow City Council

http://www.arm.arc.co.uk

Annex IV

Letter to Director, Glasgow Art Gallery And Museum - from Emmanuel N. Arinze - Chairman, West African Museums Programme

WAMP West African Museums Programme

Programme des Musées de l'Afrique de l'Ouset

B.P. 357. Dakar. Sénégal. Tel: (221) 22 50 57 Fax: (221) 22 12 33

P.O. Box 71041

Victoria Island

Lagos, Nigeria

Tel: 01-2622917, 09-2341722, 09-5234757

Fax: 01-2694642, 09-2341722

Dear Mr. Spalding

Return of Benin Objects to The Oba of Benin

I have just heard of the effort being made by Mr. Bernie Grant, MP to convince your Museum to return some Benin artefacts to the Oba of Benin as a gesture of historic reconciliation and positive response to the age long yearnings and aspirations of an aggrieved People. This gesture would not have come at a more appropriate time in the history of Benin and indeed Nigeria, as we prepare to celebrate the centenary of the great Benin Expedition of 1897.

The return of any single Benin artefact is of great significance as the object returns to the altar of our ancestors where they religiously, culturally and historically belong. Each object on the ancestral altar has a meaning and performs a function that is paramount and necessary to the life of the Edo. In a different context, environment and situation, the same object becomes sterile,. empty and just a work of art.

Having worked in Museums foreclose to twenty-five years, I do understand and appreciate that humanity should have access to the creative works of different peoples and different cultures. However this universal idea should not deprive people of their natural right to hold and to keep that which they have made and which is part of their very existence and humanity.

The sacred and unique religious ceremonies that are performed in the Palace of the Oba of Benin and which affect the life of every Edo citizen draw a huge crowd to the Palace grounds and it is significant that these ceremonies centre around the artefacts one finds on the ancestral altars.

In this regard, and in my capacity as the Chairman of the West African Museums Programme and President of the Commonwealth Association of Museums, I join my voice with those of eminent citizens like Rt, Hon. Bernie Grant, MP in appealing to you, your Museum and your Council to be gracious enough and agree to return the Benin artefacts in your Museum collection to the Oba of Benin who today is the personification of the Edo nation in all its ramifications.

This singular act of your Museum will encourage many others in our great profession to take the path of honour and join in the historic quest for restitution.

I wish you well

Best wishes

Emmanuel N, Arinze

Chairman

22-01-97

ANNEX V

LETTER FROM PROF.T.BABAWALE, CBAAC TO NEIL MACGREGOR, DIRECTOR, BRITISH MUSEUM.

OFFICE OF THE DIRECTOR

C/CBAAC183/114

16th February, 2007

Director of British Museum

Russell Square, London

EC1

Dear Sir,

COMMEMORATION OF THE 10th ANNIVERSARY OF FESTAC '77 REQUEST FOR SPONSORSHIP

IN 1977, Nigeria hosted the Second World Black and African Festival of Arts and Culture (FESTAC'77). The festival covered dance, exhibition, colloquium, durbar and a boat regatta. From all conceivable parameters FESTAC'77 was an unqualified story. It brought Africans from all over the world in a celebration of the rich cultural heritage of the African race. More importantly, it brought to the fore the invaluable contributions of Africans to the funds of universal knowledge.

The success of FESTAC'77 made it imperative that the gains of the festival should be sustained. The Centre for Black and African Arts and Civilization (CBACC) was established to perpetuate the gains of FESTAC'77.

Thirty years after the hosting of the momentous festival, CBAAC has considered it necessary to commemorate the epoch-making event. Thus a number of events have been lined up for the commemoration (Please see document attached). Proudly Nigerian Project has been commissioned by CBAAC to act on its behalf in sourcing for sponsorship and co-ordination of events.

The essence of this letter is to request that the British Museum, safely return/hand over the original 16th century ivory mask which was last worn by King Ovonramwen Nogbasi of the ancient Benin Empire in 1897 before he was exiled by Britain.

The ivory mask is the official emblem for FESTAC and a unification symbol for Nigerians and Black and African peoples worldwide. The mask is also of great significance to us as Africans.

Attempts were made to recover the mask for the 1977 FESTAC event but to no avail.

Nigeria and Britain have enjoyed a mutually warm and cordial relationship over the years. We are thefore optimistic that the British Museum would not object to this humble but historically significant request.

We await your reply in writing and look foreward to your positive response.

Thank you for your anticipated cooperation and assistance

Yours sincerely,

Prof. Tunde Babawale,

Director/Chief Executive.

REPLY OF DIRECTOR, BRITISH MUSEUM TO DIRECTOR CBAAC

THE BRITISH MUSEUM

FROM THE DIRECTOR

Prof.Tunde Babawale,

Director/Chief Executive.

CBAAC

National Theatre

Inganmu

Lagos

Nigeria

Dear Professor Babawale,

BENIN IVORY MASK

Thank you for the letter dated 23 February 2007, (which was delivered to the British Museum on 19th March 2007) concerning the Benin ivory mask, and the history of CBAAC's interest in it since FESTAC'77.

Let me assure you that the British Museum appreciates the significance of the Benin material in the collections for Nigeria, Africa and the world, and wishes to make it better understood and more accessible in Africa and worldwide. To this end, we are currently engaged in a new dialogue with the National Commission on Museums and Monuments in Nigeria. We have been invited by NCMM to offer our assistance and advice on the development of the Lagos Museum through a programme of museum development, training, professional exchanges, and capacity building for which we are seeking international backing. We are currently also involved with NCMM in a project together with the University of Frankfurt, Germany, on the material culture of Ife.

It is through programmes such as these, undertaken in partnership with our colleagues in Nigeria and at their instigation that we will best be able to further

relations between British and Nigerian museums and, most importantly, promote public understanding of Nigeria's culture and history worldwide.

Yours sincerely,

Neil MacGregor.

Akufo-Addo commissions Phase II of Kaleo solar power plant

Akufo-Addo commissions Phase II of Kaleo solar power plant

NDC panics over Bawumia’s visit to Pope Francis

NDC panics over Bawumia’s visit to Pope Francis

EC blasts Mahama over “false” claims on recruitment of Returning Officers

EC blasts Mahama over “false” claims on recruitment of Returning Officers

Lands Minister gives ultimatum to Future Global Resources to revamp Prestea/Bogo...

Lands Minister gives ultimatum to Future Global Resources to revamp Prestea/Bogo...

Wa Naa appeals to Akufo-Addo to audit state lands in Wa

Wa Naa appeals to Akufo-Addo to audit state lands in Wa

Prof Opoku-Agyemang misunderstood Bawumia’s ‘driver mate’ analogy – Miracles Abo...

Prof Opoku-Agyemang misunderstood Bawumia’s ‘driver mate’ analogy – Miracles Abo...

EU confident Ghana will not sign Anti-LGBTQI Bill

EU confident Ghana will not sign Anti-LGBTQI Bill

Suspend implementation of Planting for Food and Jobs for 2024 - Stakeholders

Suspend implementation of Planting for Food and Jobs for 2024 - Stakeholders

Tema West Municipal Assembly gets Ghana's First Female Aircraft Marshaller as ne...

Tema West Municipal Assembly gets Ghana's First Female Aircraft Marshaller as ne...

Dumsor is affecting us double, release timetable – Disability Federation to ECG

Dumsor is affecting us double, release timetable – Disability Federation to ECG