In middle school at St Peter's in Kumasi, those of us arriving from the valley were confronted daily with the ordeal of tackling the steep Roman Hill. In the 1950s, persistent lateness carried the risk of being “laid”: that is to say, being whipped in the morning assembly to deter future latecomers. It was a hot, sizzling penalty devoutly to be avoided.

So we had to evolve a method to conquer the hill. Sounding out the task from the bottom up, the novice runner might be tempted to scale the gradient in a straight line. But in stalking the hill, and plotting not to lose steam in midstream, the fastest way up was not through a straight line. To beat the gravity, the technique was in measured zig-zag motions, similar to the navigational skill of “tacking” used by sailing ships to maximize speed in spite of opposing sea winds.

Truly, necessity is the mother of innovation. We adapted, for the impending athletic feat, a work song, “Bonwere Kentenwere” [Kente weavers at Bonwere] which the venerable Ephraim Amu had scored for piano interludes.

At the signal “Go”, we dashed up the hill - swaying left, right, left, right - pacing to the refrain in the song “Kro kro, hi hi; Kro kro, hi hi”. Halfway up the hill, and needing an extra boost for the finish, we geared the tempo to “Kro hi ko, Kro hi ko”. The vigour so surged from Amu's spirit, propelled us to the hilltop in no time flat. In that particular matter of life or whip, Ephraim Amu was our very messiah.

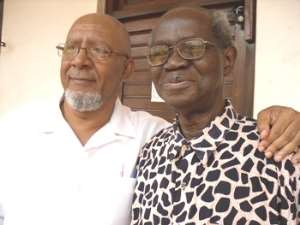

Prof Kwabena Nketia |

In lieu of “twisting” and “shouting”, GBC offered fresher glimpses into a world we already knew at our toe tips; but that world was now packaged with sparkling richness. At the end of each performance, the camera turned for commentaries, such as, the stories behind the lyrics, the meanings in the elegant moves of the dancers, the poetry in the drums, the instrumental improvisations, and a taste of what to expect next.

Presiding over the interpretations, in proud splendour, was the veritable duo – the late Dr A.A.Y. Kyerematen, and the maestro Prof J.H. Kwabena Nketia. Though the drums, songs, poetry, and dances were familiar, they were relayed to signal new delightful graces. The grass was green right there in our own native turf!

Prof Nketia's esteem preceded him through the contacts with Ephraim Amu at the Presbyterian Training College at Akropong, Akwapim (1937 – 1944) where the young Nketia taught Music and Twi, and collaborated with C.A. Akrofi in projects in Twi orthography and school texts. From 1944 – 1949, he studied at the University of London, and the Trinity College of Music. At the University of Ghana (1952 – 1979) he started from the Sociology Department (encouraged by Dr K.A. Busia), to the birth of the Institute of African Studies (inaugurated by Dr Kwame Nkrumah). Soon, he was the bona fide concurrent Director of both the Institute and the School of Music, Dance, and Drama.

It was not until about 1980 that I had the good luck of meeting Prof Nketia and his dear wife, Auntie Lily. He had come to the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) to the Dept of Music and the Institute of Ethnomusicology where he taught and supervised the doctoral dissertations of American and international students.

His admirers in California were not destined to love and keep him for long in the Golden State. In 1983, the University of Pittsburgh made him an offer he couldn't refuse: the Andrew W. Mellon Professor of Music. Soon thereafter he was made Chairman of the Music Department from 1986 – 1989, to add his subtle flavours to the courses in Ethnomusicology.

In June 1988, the China Conservatory of Music, Beijing, invited him to design a six-week course in Ethnomusicology for scholars in music research. From China, he was in Canberra, Australia, to participate and give a plenary address on “Exploring Intercultural Dimensions of Music in Education.” From 1989 to 1992, Prof Nketia served in the Overseer's Committee of Harvard University's Department of Music.

Prof Nketia cherishes the presentation of a “Festschrift” on him by UCLA (October 21, 1989). Conferred in two volumes titled “African Musicology: Current Trends”, the “Festschrift” celebrated “the international influence and recognition of one of the world's premier humanistic scholars, ethnomusicologists, and music educators, Professor J.H. Kwabena Nketia.” The event confirmed the deep respect in which Prof Nketia was held worldwide.

In the following month, Harvard honoured him to give the Charles Seeger Memorial Lecture. As Prof Nketia recalled, “The hall was packed and many people were sitting on the floor.” He described the event as “a sort of crowning thing in my career as an Ethnomusicologist in the United States.” From Pittsburgh, Prof Nketia was at Kansas University as Langston Hughes Professor of African and African-American Studies for the Spring of 1992.

Perusing Prof Nketia's CV is a dizzying affair. He is unique in having covered so much ground in one lifetime. The depth and richness in his intellectual experiences are extraordinary. No doubt he has tasted and enjoyed every fulfilment except boredom. The commitment leveraged by his ability to recall cadences, lyrics and motifs helped to blend and score music wherever he found them.

Hear him: “the materials I encountered in my research enabled me to develop my composition theory, to determine where I could move from tradition to modernity without masking my African voice or losing my African identity. This has been particularly important to me as a composer.”

He leaped off in the Gold Coast, in 1949, with his first book “Akanfoo Nnwom Bi” (Oxford Press), followed by his two classics “Funeral Dirges of the Akan People” (first published by the University of Ghana, and later by Greenwood Press), and “The Music of Africa” (W.W. Norton and Co), now translated into Japanese and Chinese. There was not a dull moment since. With the literary “virtuosa” Efua Sutherland, and the photographer Willis Bell, they founded the Afram Publications in the 1970s, and published “Anwonsem” (Akan Poetry), and “The Poetry of Atumpan Drums”, and others.

In preserving and sharing Ghana and Africa's rich heritage, he now has over 200 publications and more than 80 musical compositions to his credit. His own impetus has taken him to major musical and intellectual centres across the continents as the de facto Ethnomusicologist ambassador of Ghana. The man and his works are national treasures to be conserved for posterity.

As I write this piece, Prof Nketia - at age 88 (he was born June 22, 1921 at Mampong, Asante) has completed four manuscripts, each ready for publication as a complete book, and should attract prospective publishers:

1. Sound Instruments of Ghana, Vol I. Organology, Performance Practices, and Cultural Contexts.

2. Sound Instruments of Ghana, Vol II. Sound Instruments and Cultural policy. (Re-Defining the Boundaries of Tradition).

3. AYAN – The Poetry of Atumpan Drums. Vol I. A Study of the Themes, Referential System, and Performance Dynamics.

4. AYAN – The Poetry of Atumpan Drums. Vol II. Anthology.

Inasmuch as peculiar intelligences drive gifted learners and great achievers, Prof Nketia fits the Intrapersonal mode. He is reflective and examines perspectives to feel his own way. He avoids the mundane and gossip, and thinks largely in terms of ideas. He enjoys his private space, and sets goals which he achieves quietly. Though he tends to be alone, he is hardly lonely. He achieves best through listening, in his case through the poetry in music while composing his own songs, and sharing them.

At the core of Prof Nketia's being is that absolute modesty: “Ade pa nkasa”, as we say in Akan; the selflessness; the sense of purpose; his ability to relate to the young like peers; and lastly, those easy smiles that defy understanding.

Prof Nketia has compiled a selection of his music into CDs and cassette tapes in (ICAMD-DMV) Vols. 1 – 4 as a testimony of his lifelong interest in this creative field. He says in the companion booklet: “A hunter is the person whose venison lies on the hot grill and not the one whose venison is in the bush.” The collections are improvisations for symphony and orchestral performances with strings, percussions, piano, flutes, and horns, and are digitised by his archival assistant Andrews Agyemfra-Tettey, at the School of Performing Arts, University of Ghana, Legon.

[How I imagine, and wish the late impresario Duke Ellington were here to score and perform the Nketia suites for symphony and orchestra - at the Carnegie Hall (New York), and the National Theatre (Accra) - with Harry Belafonte, Miriam Makeba, Billy Holiday and Ella Fitzgerald singing in Akan! What wonderful worlds that would be!]

The source materials for his artistry were in the wellsprings of the traditional songs the young Kwabena Nketia absorbed from his grandmother, Yaa Amankwaa, and her cousin, the “Adowa hemmaa”. The stimulus began in small, pure streams; but he expanded and spread them out like winged rivers cascading into wider channels; he made his new stuff fit the old pieces like puzzles. The secrets were in his improvisations and innovations; they both sported his considerable qualities, and hatched a brave new genre – the contemporary African art music.

By Anis Haffar

The author consults and teaches internationally in Competent Writing Skills, Teaching Methodologies for Effective Learning, and Youth Leadership Training.

E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.gateinstitute.org

There’s nothing you can do for us; just give us electricity to save our collapsi...

There’s nothing you can do for us; just give us electricity to save our collapsi...

Ghanaian media failing in watchdog duties — Sulemana Braimah

Ghanaian media failing in watchdog duties — Sulemana Braimah

On any scale, Mahama can't match Bawumia — NPP Youth Organiser

On any scale, Mahama can't match Bawumia — NPP Youth Organiser

Never tag me as an NPP pastor; I'm 'pained' the 'Akyem Mafia' are still in charg...

Never tag me as an NPP pastor; I'm 'pained' the 'Akyem Mafia' are still in charg...

Your refusal to dedicate a project to Atta Mills means you never loved him — Kok...

Your refusal to dedicate a project to Atta Mills means you never loved him — Kok...

2024 elections: I'm competent, not just a dreamer; vote for me — Alan

2024 elections: I'm competent, not just a dreamer; vote for me — Alan

2024 elections: Forget NPP, NDC; I've the Holy Spirit backing me and nothing wil...

2024 elections: Forget NPP, NDC; I've the Holy Spirit backing me and nothing wil...

2024 elections: We've no trust in judiciary; we'll ensure ballots are well secur...

2024 elections: We've no trust in judiciary; we'll ensure ballots are well secur...

Performance tracker: Fire MCEs, DCEs who document Mahama's projects; they're not...

Performance tracker: Fire MCEs, DCEs who document Mahama's projects; they're not...

Train crash: Railway ministry shares footage of incident

Train crash: Railway ministry shares footage of incident