Reference is made to the letter from Philippe de Montebello, Director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art (1), New York, which was published in AFRIKANET on Friday, 18 April, 2008. http://www.afrikanet.info/. In his letter, Philippe de Montebello refers to my article entitled “Is Legality still a viable concept for European and American Museum Directors?” http://www.afrikanet.info/index. The Director of the Metropolitan does not address the main point of my article, namely, that the arguments the European and American museums present in defence of their holding of stolen African cultural objects are extremely weak. It seems the director is more interested in the picture inserted in the article than in the serious comments on legality. I shall therefore only comment on the points raised in his letter.

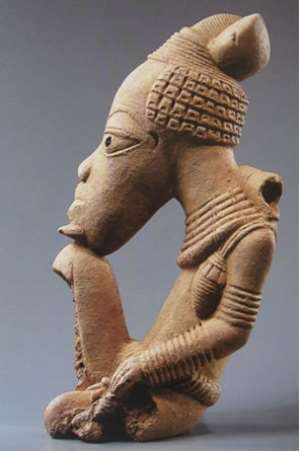

We are sorry that the Director of the Metropolitan Museum had to go to so much trouble in order to identify the Nok terracotta. Incidentally, why must a Nok sculpture be described as “haunting, strange-looking object”? This description comes from a museum director who has artworks from the Egyptians, Guro, Lobi, Dogon, Bamana, Senufo, Baule, Lumbo, Igbo, Fan Yoruba, Chokwe, etc among his collections. I thought we had long moved away from the period when the Europeans and Americans described whatever came out of Africa in these terms. Or are we going back to those days when an unbridgeable difference was assumed to exist between African art and European art? Surely, after the influence of African art on modern art and after so many exhibitions on African art, some organized by the Metropolitan Museum, such a description sounds somewhat odd, especially coming from a Director of one of the leading museums of the West.

The “haunting, strange-looking object” which the director could not identify is one of the three terracotta pieces which were bought by the French and kept in the Louvre (another “universal museum”) even though the objects were on the Red List of ICOM (International Council of Museums) which contains a list of items which are forbidden to be exported. (See Annex 1 below). This fact was known to the French but they did not care for the rules and it took the intervention of ICOM to bring the matter to discussion and to the embarrassment of the French who had bought the pieces in 1999 for the planned museum, Musée du Quai Branly. (2) Finally, France acknowledged the ownership of Nigeria in those pieces and signed an agreement by which Nigeria loaned the pieces to France for a period of twenty-five years (renewable). Did Montebello never hear of this story?

That the Metropolitan Museum does not own a Nok or Ife object should not lead to the conclusion by the Director of the Metropolitan Museum that “Nigeria seemed to have produced no art before the much later Benin period, well represented at the Metropolitan Museum”. Is the premise of this conclusion that what does not exist in the Metropolitan Museum does not exist and cannot exist? Montebello himself has said in his second paragraph that he “also discovered that more than 2000 years ago as well an Ife culture in Nigeria produced sculpture”. First a discovery of Ife and then a conclusion that nothing existed before Benin? Attention may be drawn to the information on Nok Terracotta issued in 2000 by the Department of Arts of Africa, Oceania, and the Americas, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, in the Timeline of Art History http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/nok/hd_nok.htm (October 2000) (ANNEX 2) The note refers to an image from the Minneapolis Institute of Arts. That image depicts a Nok figure of a seated dignitary the features of which are very similar to those of the image the Director of the Metropolitan Museum could not easily identify. The Minneapolis Institute of Arts note states that: “A few of the remarkable characteristics that distinguish Nok pieces from terracottas of later cultures in Nigeria include the triangular, pierced eyes; the elaborate coiffure and beard; and the placement of the ears.” http://www.artsmia.org/viewer/detail.php?v=12&id=5368

If the export of Nok or Ife objects from Nigeria is strictly forbidden, it is among other reasons, to preserve them in their original setting so that archaeologists can study them before the plunderers get their hands on them and sell them to the museums of the West. The Director of the Metropolitan Museum surely knows that these objects are also on the Red List of ICOM.

If the Metropolitan Museum has not been able to convince the Government of Nigeria to loan one object of each of the great cultures of Nigeria, there must be some reason which must have been explained by the Nigerian authorities. One cannot comment on this point without first studying the relevant correspondence.

The statement that “Dr. Opoku believes all Nok, Ife, and Benin pieces outside of Nigeria should be returned to Nigeria; that all works produced on its territory should remain there“ is surely incorrect and the maker of the statement knows it. As a person of culture who has spent a considerable part of my life visiting various museums all over the world, I reject very strongly this statement. It is an attempt to attribute to me an extreme position which can be easily dismissed instead of dealing with the serious arguments presented in detail (some would even say too much detail) in my various articles which are freely available on the internet.

a) I have not been concerned in my articles with all Nok, Ife and Benin pieces. I have been concerned mainly with those pieces of African culture which have been stolen, looted, illegally exported or which have dubious provenance and are in museums and their depots in Europe and America. We have not addressed the issue of private ownership. We also believe that some pieces may have been legally and legitimately acquired. The museum directors may wish to throw all in one basket in order to build up a better defence. That is their choice of strategy but this amalgam is neither honest nor very helpful.

b) Those objects which have archival or religious or ritual significance will have to be returned to the countries or communities of origin.

c) Those museums that are holding a large quantity of Benin pieces, British Museum, 700, Ethnological Museum, Berlin, 600, should return some of these to Nigeria. “Some” in my understanding does not mean “all”. The nightmare of the museum director of waking up one morning and finding that all the African pieces in his museum have disappeared has no foundation in reality but is a fiction of his troubled imagination.

d) The museums holding illegally acquired Nigerian cultural objects will have to acknowledge Nigerian ownership in these objects.

e) The Director of the Metropolitan Museum knows that there are many sculptures from Nok, Ife and Benin outside of Nigeria and in the West, if not in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Those interested in African art have already enough information at their disposal in the various museums and in various books, such as Philippe de Montebello said he consulted. There is no danger of these civilizations becoming unknown.

f) Philippe de Montebello writes about the importance of people seeing these objects in the museums. This is true but equally important, if not more important, is the need of the peoples of the countries of origin to have access to these objects in their own countries. The American or the British may widen his knowledge about the world in seeing African sculptures in the museums but do Africans not have any need also to learn about their own culture and the cultures of others?

g) We are all interested in cultural objects being accessible to others but this must be done on fair and equal basis and definitely not to the detriment of the countries/communities of origin.

h) If Philippe de Montebello cannot identify Nok sculpture as he appears to be saying, how then will he negotiate and correspond with the Nigerian authorities? Is he seriously saying he can only recognize pieces from the cultures represented in his museum?

i) Those interested in my views on the question of the restitution of African cultural objects may wish to read my articles which are easily available at AFRIKANET and elsewhere on the internet.

j) We should try to make it possible for all peoples to view objects from all cultures and not only those in the Euro-American world. So far when Western museum directors speak of mankind, they have only meant their kind. When are they going to start thinking about sending some European masterpieces to African museums so that Africans can also assess what Europeans have been able to achieve? They could send to Accra, Kumasi, Lagos, Abuja, Bamako, Cape Town, Dakar and Yaounde some Arcimboldo, Braque, Botticelli, Bourgeois, Bernini, Cézanne, Chagall, Courbet, Dürer, Dali, Gaugin, Giorgione, Klee, Klimt, Manet, Monet, Munch, Miró, Nolde, Picasso, Pollock, Raffael, Rembrandt, Rodin, Schiele, Tizian, Van Dyck, Warhol, etc. Or should it always be a one-way traffic?

As most readers will recall, the Director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, was one of the signatories of the so-called Declaration on the Importance and Value of the Universal Museums (2002) by which the largest museums- Louvre Museum, Paris, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, State Museums, Berlin, Solomon Guggenheim Museum, New York, The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, The Museum of Modern Art, New York and others-tried to secure for themselves immunity against the growing claims for the restitution of stolen art objects in their museums and also alleged that stolen objects which had been in their museums for a very long time have become part of the cultures of the countries where they are located. Though the British Museum was the instigator of the initiative which was aimed at countering the growing political pressure of Greece for the restitution of the Parthenon/Elgin Marbles, the BM cunningly did not sign it. To explain and make explicit the assumptions and insinuations of the champions of the so-called “universal museums” implicit in the letter of Philippe de Montebello would take another article. The reader is therefore advised to consult the following excellent articles: Mark O'Neill, “Enlightenment Museums - universal or merely global” http://www.elginism.com/20071012/826/; Tom Flynn, “The Universal Museum – a valid model for the 21 century?” (http://www.tomflynn.co.uk/)

It should also be added, though this may not mean much to some European and American museum directors, it is not simply a question of wanting or not to return cultural objects. There are laws and rules governing these matters. The 1970 UNESCO Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property as well as the 1995 UNIDROIT Convention on Stolen or Illegally Exported Cultural Objects contain provisions which relate to restitution. Various United Nations and UNESCO resolutions deal with the question of restitution and the need to return cultural objects to their countries or communities of origin. We have also had various conferences, such as, the recent UNESCO International Conference, The Return of Cultural Property to its Countries of Origin, 17-18 March, 2008, Athens, which urged museums to initiate dialogues on the return of important cultural property to the country and community of origin. Most legal systems have provisions relating to unlawful acquisition of property which are also relevant. The ICOM Code of Ethics contains provisions on the acquisition of objects by museums and on restitution (http://icom.museum/ethics.html.) It is therefore not only a question of will but also of law.

We have written articles to urge the restitution of stolen cultural objects. Philippe de Montebello, whilst rejoicing in the possession of Benin objects (including one of the two Idia ivory hip masks, the symbol of FESTAC), by his museum, the Metroplolitan Museum of Art, New York, complains about his inability to persuade the Nigerian Government to provide his museum with Nok and Ife objects he knows are on the Red List of ICOM and therefore illegal to export. He does not say a word about restitution. Clearly the epistemological revolution which is required if the large museums are to play a truly universal role is neither for today nor for tomorrow. Philippe de Montebello sees the world only from the vantage point of those in New York or London.

“Whether the signatories to the declaration considered how their joint utterance might be received by the international cultural community, or the extent to which it might polarise museum professionals remains unclear. However, it is hard to see how a potentially divisive and provocative policy document could have been constructed with such scant disregard for the broader museum community, which was not consulted.” Tom Flynn on the Declaration on the Importance and Value of Universal Museums, “The Universal Museum – a valid model for the 21 century?” (http://www.tomflynn.co.uk/)

Kwame Opoku 20 April, 2008.

NOTES

(1) The Metropolitan Museum is described in its own press release of 8 January, 2008 http://www.metmuseum.org/press_room/7D as follows:

“The Metropolitan Museum of Art is the largest museum in the Western Hemisphere, and the world's most encyclopedic art museum under one roof. Founded in 1870, its permanent collections, housed in 17 curatorial departments, embrace more than two million works of art spanning 5,000 years of world culture, from prehistory to the present, from every part of the globe, in all artistic media, and at the highest levels of creative excellence.”

(2) http://www.mcdonald.cam.ac.uk/projects/iarc/culturewithoutcontext/issue10/news.htm

K.Opoku, “Benin to Quai Branly: A Museum for the Arts of the Others or for the Stolen Arts of the Others?” http://www.museum-security.org/wordpress/

http://www.kmtspace.com/nok.htm

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nok

http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/entertainment/arts/1790882.stm

http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9F06E7DE113AF936A15752C1A9669C8B63

http://hum.lss.wisc.edu/hjdrewal/Nok.html

Bernard Dupaigne, Le Scandale des arts premiers: la véritable histoire du musée du quai Branly. Paris, Mille et une nuits, 2006.

For those who need an excellent introduction to Nok culture, one can recommend, The Nok Culture - Art in Nigeria 2500 years ago by Gert Chesi and Gerhard Meerzeder, Prestel, Munich, Berlin, London, New York,2006.

ANNEX. 1

ICOM RED LIST

Red List Africa I About the objects I ICOM and the protection of heritage I Red List Home

The looting of archaeological items and the destruction of archaeological sites in Africa are a cause of irreparable damage to African history and hence to the history of humankind. Whole sections of our history have been wiped out and can never be reconstituted. These objects cannot be understood once they have been removed from their archaeological context and divorced from the whole to which they belong. Only professional archaeological excavations can help recover their identity, their date and their location. But so long as there is demand from the international art market these objects will be looted and offered for sale.

In response of this urgent situation, a list of categories of African archaeological objects particularly at risk from looting was drawn up at the Workshop on the Protection of the African Cultural Heritage held in Amsterdam from 22 to 24 October 1997. Organised by ICOM (International Council of Museums), within the framework of its AFRICOM programme, it brought together professionals from African, European and North American museums to set up a common policy for fighting against the illicit traffic in African cultural property, and to promote regional and international agreements.

The Red List includes the following categories of archaeological items:

• Nok terracotta from the Bauchi Plateau and the Katsina and Sokoto regions (Nigeria)

• Terracotta and bronzes from Ife (Nigeria)

• Esie stone statues (Nigeria)

• Terracotta, bronzes and pottery from the Niger Valley (Mali)

• Terracotta statuettes, bronzes, potteries, and stone statues from the Bura System (Niger, Burkina Faso)

• Stone statues from the North of Burkina Faso and neighbouring regions

• Terracotta from the North of Ghana (Komaland) and Côte d'Ivoire

• Terracotta and bronzes so-called Sao (Cameroon, Chad, Nigeria)

These objects are among the cultural goods most affected by looting and theft. They are protected by national legislation, banned from export, and may under no circumstances be put on sale.

An appeal is therefore being made to museums, auction houses, art dealers and collectors to stop buying them.

This list is of objects which are particularly at risk, but in no way should it be considered exhaustive. The question of the legality of export arises with regard to any archaeological item.

Press Releases

NIGERIA'S OWNERSHIP OF NOK AND SOKOTO OBJECTS RECOGNISED

________________________________________

5 March 2002

ICOM welcomes the French government's decision to recognise Nigeria's ownership of three Nok and Sokoto artefacts.

The objects in question were acquired by France in 1999 for the planned Musée du Quai Branly and belong to the categories of archaeological objects identified on the ICOM Red List as being amongst the types of cultural goods most affected by thefts and looting. They are protected by national legislation and banned from export: on no account must they be purchased or offered for sale.

ICOM also applauds Nigeria's generous decision to deposit the artefacts concerned with the Musée du Quai Branly , to be exhibited with the museum's permanent collection, for the exceptionally long period of 25 years (renewable), in exchange for France's recognition of its ownership. ICOM recommends that visitors should be clearly informed of the precise status of these objects and the way in which they were discovered.

ICOM would like to take this opportunity to issue a reminder that the looting of archaeological items in Africa causes irreparable damage, destroying vital evidence of the history of the continent and of mankind as a whole. Museums must therefore take a lead in combating the illicit trade in cultural goods, by adopting scrupulous acquisition policy in line with the ICOM Code of Professional Ethics for museum professionals.

ANNEX 2

Nok Terracottas (500 B.C.–200 A.D.)". In Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/nok/hd_nok.htm (October 2000)

Area of Nigeria where terracotta heads were first discovered.

Seated Dignitary

The Minneapolis Institute of Arts

Seated Dignitary, c. 250 B.C.

Nok People, Africa, Eastern Nigeria, Nok Plateau

Fired Clay; H. 36 1/4 x W. 10 7/8 x D.14 in.

The John R. Van Derlip Fund

http://www.artsMIA.org

In 1943, tin mining in the vicinity of the village of Nok near the Jos Plateau region of Nigeria brought to light a terracotta head, evidence of the oldest known figurative sculpture south of the Sahara. Although stylistically related heads, figures, animals, and pottery shards have been found in a number of Nigerian sites since that time, such works are identified by the name of the small village where the first terracotta head was discovered. Artifacts continue to be unearthed without documentation of the context in which they were buried, a lack of extensive archaeological study that has severely limited our understanding of Nok terracottas. One of the earliest African centers of ironworking and terracotta figure production, the Nok culture remains an enigma.

Most Nok sculpture is hollow and coil-built like pottery. Finely worked to a resilient consistency from local clays and gravel, the millennia-long endurance of these ancient objects is a testament to the technical ability of their makers. This is not to say that Nok sculpture has survived unchanged by time. The slip (the mixture of clay and water used to give pottery surfaces an even texture) of many Nok terracottas has eroded, leaving a grainy, pocked exterior that does not reflect their original smooth appearance. Most of the Nok sculpture found consists of what appear to be portrait heads and bodies fragmented by damage and age. The recovered portions of the baked clay bodies that have survived show that they were sculpted in standing, sitting, and genuflecting postures.

Nok head fragments were once part of entire bodies and are the most renowned objects within the corpus known to date. These objects are so highly varied that it is likely they were modeled individually rather than cast from molds. Although terracottas are usually formed using additive techniques, many Nok pieces were sculpted subtractively in a manner similar to carving. This distinctive approach suggests that a comparable wood-carving tradition may have influenced them. The heads of Nok terracottas are invariably proportionally large relative to the bodies, and while not enough is known of Nok culture to explain this apparent imbalance, it is interesting to note that a similar emphasis of the head in later African art traditions often signifies respect for intelligence.

Although every Nok head is unique, certain stylistic traits are found throughout the corpus of known work. Triangular eyes and perforated pupils, noses, mouths, and ears combine to depict men and women with bold, abstracted features. Perhaps the most striking aspects of Nok sculptures are the elaborately detailed hairstyles and jewelry that adorn many of the figures. The variety, inventiveness, and beauty of their design is a beguiling record of cultivated devotion to body ornamentation. But as captivating as these embellishments are, the range of expression in Nok terracottas is far from limited to depictions of idealized health and beauty. Some pottery figures appear to depict subjects suffering from ailments such as elephantiasis and facial paralysis. These "diseased" visages may have been intended to protect against illness but, beyond conjecture, their meaning and the significance of Nok sculpture in general are still unknown.

The great sophistication of Nok terracottas has led some scholars to believe that an older, as yet undiscovered tradition must have preceded Nok terracotta arts. It has also been suggested that Nok terracottas have some sort of relationship to later portrait arts, such as those of Ife, but this is currently unproven. Masterful relics severed from their predecessors and successors by the passage of time, Nok terracottas currently occupy an important but isolated space in the history of African art.

Department of Arts of Africa, Oceania, and the Americas, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

________________________________________

ANNEX 3

NOK TERRACOTTA ACQUIRED ILLEGALLY BY FRANCE

Wikipedia.

Seated person. Nok cultural object, 500 BC - 500 AD.

Quai Branly, depot of Louvre, inv.No.70.1998.11. One of the three stolen items from Nigeria now in Paris.

Avoid pre-registered SIMs, buyer and seller liable for prosecution – Ursula Owus...

Avoid pre-registered SIMs, buyer and seller liable for prosecution – Ursula Owus...

Election 2024: Mahama has nothing new to offer Ghanaians, Bwumia is the future –...

Election 2024: Mahama has nothing new to offer Ghanaians, Bwumia is the future –...

OSP files fresh charges against ex- PPA Boss

OSP files fresh charges against ex- PPA Boss

Withdraw unreasonable GH¢5.8m fine against former board members – ECG tells PURC

Withdraw unreasonable GH¢5.8m fine against former board members – ECG tells PURC

Akroma mine attack: Over 20 armed robbers injure workers, steal gold at Esaase

Akroma mine attack: Over 20 armed robbers injure workers, steal gold at Esaase

Those who understand me have embraced hope for the future — Cheddar

Those who understand me have embraced hope for the future — Cheddar

Ghana will make maiden voyage into space should Bawumia become President — Chair...

Ghana will make maiden voyage into space should Bawumia become President — Chair...

Train crash: Despite the sabotage, we shall not be deterred and will persevere —...

Train crash: Despite the sabotage, we shall not be deterred and will persevere —...

Tema-Mpakadan railway project a perversion of the original viable concept design...

Tema-Mpakadan railway project a perversion of the original viable concept design...

Train crash: Elsewhere, everyone involved in the test will either be fired or re...

Train crash: Elsewhere, everyone involved in the test will either be fired or re...