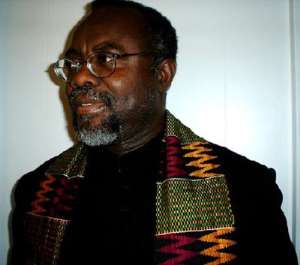

When he died very recently, most major Ghanaian newspapers sparingly described him as having served as a treasurer of the ruling New Patriotic Party (NPP). But for any Ghanaian of my generation, the Africanization Generation, gauging by the period of our births, that is, Mr. Kwesi Brew ranked high on the list of the first generation of postcolonial Ghanaian writers. He had distinguished himself as a quite formidable poet. And while in secondary school, I had envisaged the man as, perhaps, the finest Ghanaian poet. For he handled the English language with such deft and depth as to readily make him stand head-and-shoulders above the rest. And so for me, personally, it is rather a crying shame that I never met the man.

And so I was quite elated to learn, by reading his poignant tribute to Kwesi Brew, that, indeed, my paternal uncle, Mr. Cameron Duodu, had been fast friends with the esthetically inimitable Mr. Kwesi Brew. I was also deeply touched because Uncle Duodu – actually, according to Akan tradition, he is my father – also recently lost his wife, the famous Ms. Beryl Karikari. At the time, I had thought of writing a terse article paying homage to both Wofa Duodu and his late wife. I had actually attempted to put ink to paper but had to promptly abandon the entire noble enterprise. For there was one basic problem: besides blood ties, I knew practically next to nothing about Mr. Cameron Duodu.

The problem stems from a feud that my late father, I was to learn later, had with his own father, Opanyin Kwaku Gyimah, about the same year as the founding of the University of Ghana. My father had passed the entrance examination to GSTS, in Takoradi. In 1948, GSTS was a technical teachers' training college. His father, who was a renowned and quite successful storekeeper (businessman, in contemporary parlance), had determined it better to let my father truncate his academic ambitions in order to work with him at his store, located in the Opera section of Accra. My grandfather traded in Western-tailored suits, hats and shoes. My father once told me that so popular was his businessman father that Agya Koo Gyimah, as he was also affectionately called, had been nicknamed “London Opinion.” It appears that most of the European residents of Accra at the time, one way or another, had had commercial dealings with him. Of course, I would also later learn that, indeed, “London Opinion” was also the name of a sewing material.

And so, perhaps, Agya Koo Gyimah had been nicknamed after one of the favorite fabrics, of the time, in which he briskly traded. But whether it was the proverbial river which crossed the path, or the path it was which crossed the river, remains prime grist – and yarn – for a future narrative.

What struck me as tragically bizarre and outright odd, regarding the rather insolently piddling obituaries on Mr. Kwesi Brew published in the Ghanaian newspapers, was the strange suggestion that the man had barely eked out a decent existence in the very society whose rebirth he had witnessed, first-hand, and in whose development as a postcolonial nation-state he had actively participated. For as Wofa Duodu, in his inimitably eloquent style remarked, I believe, also quoting the London Guardian newspaper, the pioneering “Brew was recruited [in]to the early Ghanaian diplomatic service and worked in the UK, France, Germany, India and the USSR, before serving as [Ghana's] Ambassador in Mexico, Lebanon and Senegal…. Later,…he went into business, first joining his younger brother[,] Atu…as resident director of the Takoradi Flour Mills from 1975-81. He then developed his own company, the Golden Spoon Flour Mills, based in Tema” (see “Good Bye, Kwesi Brew,” Newtimesonline 10/16/07).

Evidently, none of the preceding sterling achievements meant anything to the Ghanaian newspapers that briefly and almost flippantly reported the momentous passing of Mr. Kwesi Brew. It is also quite dolorously interesting that my uncle, Cameron Duodu, makes the following telling observation: “The shock to me was all the greater because although I make it a point to try and read the Ghanaian newspapers that are online, I hadn't come across the terrible news that Kwesi Brew was dead. Rather, it was a casual glance at the obituaries section of the London Guardian that had me gasping: 'Oh no! Not Koo?'”

Needless to say, Uncle Duodu is hardly all by himself vis-à-vis the insultingly piddling coverage that was accorded Ghana's finest poet of the first postcolonial generation. Interestingly and significantly, had any of the Ghanaian journalists who reported the passing of Mr. Brew bothered to open the biographical head-note in Professors Kojo Senanu and Theo Vincent's edited anthology titled “A Selection of African Poetry” for “O”-Level School Certificate Examination, they would have reverently acquainted themselves with the same highlights of Mr. Brew's rich, long and eventful life and career as documented by the Guardian newspaper of London. Unfortunately, in a country in which literary and intellectual mediocrity is prized over and above the latter's super-ordinate counterpart of literary and intellectual discipline, I am not in the least bit surprised that Uncle Cameron Duodu learned about the momentous, to speak less of the traumatic, passing of Mr. Kwesi Brew from a London newspaper, and not one that is published in the very land of Mr. Brew's birth and death. For, to be frank with you, dear reader, one ought to have actually surfed the 'Net expressly looking for Mr. Brew's obituary, else it would have been virtually impossible to locate it. For vacuously identifying the deceased as a former treasurer of the New Patriotic Party, left the critical and reasonably well-educated reader more confused than enlightened.

I was also elated by my uncle's dead-on poignant quote from Brew's poem “The Mesh,” although I also firmly believe, perhaps against the grain, that the single greatest poem on the Anlo-Ewe littoral culture was written by the Akan-Fante Mr. Kwesi Brew. The poem is titled “The Sea Eats Our Land.” The latter poem has also been credited with having prompted the Ghanaian Government to erect a sea-defense system – or levee – for the protection of the Keta area of southeastern Ghana against massive soil erosion. Another concrete proof of the pen being mightier than the sword.

*Kwame Okoampa-Ahoofe, Jr., Ph.D., is Associate Professor of English and Journalism at Nassau Community College of the State University of New York, Garden City. He is the author of “The New Scapegoats: Colored-on-Black Racism” (iUniverse.com, 2005). E-mail: [email protected].

April 23: Cedi sells at GHS13.66 to $1, GHS13.07 on BoG interbank

April 23: Cedi sells at GHS13.66 to $1, GHS13.07 on BoG interbank

GRA clarifies tax status of resident individuals earning income abroad

GRA clarifies tax status of resident individuals earning income abroad

2024 elections: NDC to officially unveil Jane Opoku-Agyemang as running mate tom...

2024 elections: NDC to officially unveil Jane Opoku-Agyemang as running mate tom...

Bawumia embarks on working visit to Italy and the Vatican to boost bilateral tie...

Bawumia embarks on working visit to Italy and the Vatican to boost bilateral tie...

Senegal's new leader calls for a rethink of the country's relationship with the ...

Senegal's new leader calls for a rethink of the country's relationship with the ...

Chairman Kingsley Owusu Brobbey calls for Privatization of Electricity

Chairman Kingsley Owusu Brobbey calls for Privatization of Electricity

Gov't to consolidate cash waterfall revenue collection accounts

Gov't to consolidate cash waterfall revenue collection accounts

Gov't to settle lump sum for retired teachers by April 27

Gov't to settle lump sum for retired teachers by April 27

Former PPA CEO granted GH₵4million bail

Former PPA CEO granted GH₵4million bail

NPP trying to bribe us but we‘ll not trade our integrity on the altar of corrupt...

NPP trying to bribe us but we‘ll not trade our integrity on the altar of corrupt...