Mamadou Diallo was meant to meet his best friend to watch the Champions League after evening prayers.

Twenty minutes before their rendezvous, he received a phone call. His friend, also called Mamadou, had been shot dead.

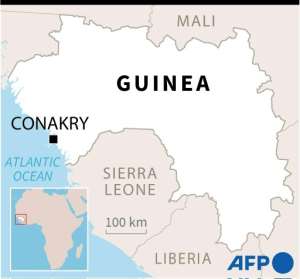

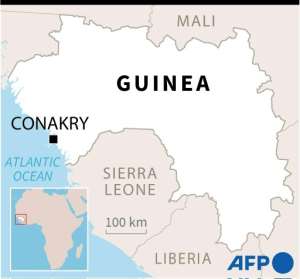

It was a November evening in 2018 in Wanindara, a northern suburb of Guinea's capital Conakry and flashpoint for the opposition to the country's president, Alpha Conde.

"I couldn't hold myself together," Diallo said, describing the moment he saw his friend's corpse.

Guinea. By Gillian HANDYSIDE (AFP)

Guinea. By Gillian HANDYSIDE (AFP)

He now documents killings and police violence in the neighbourhood for a coalition of opposition civil-society groups.

Two years on from his friend's death, violence has only become more regular.

Guinea is holding a referendum on Sunday on whether to change the constitution, in one of the most contested votes in the poor West African state in recent years.

The new text would bring needed change such as enshrining gender equality, the government argues.

But critics fear the real motive is to reset presidential term limits, allowing Conde, 82 next week, to run for a third term this year.

Guineans have demonstrated en masse against the possibility since mid-October, in protests where at least thirty protesters and one gendarme have been killed, according to an AFP tally.

Precise figures are hard to come by, but many of the killings are thought to have occurred in Wanindara.

A mostly-Fulani neighbourhood some 20 kilometres (12 miles) from central Conakry, Wanindara has a village feel beyond the thronged main road.

Narrow, pot-holed dirt roads lead to houses surrounded by clucking chickens, and hung-up laundry.

Cattle graze on large rubbish heaps while stray dogs shelter from blistering heat beneath parked lorries. Women in wax-print dresses draw water from communal wells.

The area is a stronghold of the former French colony's leading opposition party, the Union of Democratic Forces of Guinea (UFDG).

Residents complain of arbitrary violence and routine disappearances.

"The police come into the area and fire live rounds," said Ibrahim Barry.

He said his brother Idrissa was killed on February 13 while going to play football.

Sherif Balde, a truck driver, said his son Ibrahima, 14, was hustled into a white pick-up and has not been seen for two weeks.

A boy walks past a wall plastered with posters to vote 'Yes' in Sunday's referendum. By JOHN WESSELS (AFP)

A boy walks past a wall plastered with posters to vote 'Yes' in Sunday's referendum. By JOHN WESSELS (AFP)

"We're scared," he told AFP, adding that he was not sure who took him.

The government denies wrongdoing, and in a deeply polarised political climate, it has accused the opposition of provoking violence and of using casualties as a propaganda tool.

"There really is a type of urban guerilla warfare that's taking hold," said Guinea's suave security minister, Damantang Albert Camara, sitting in an air-conditioned office before a framed portrait of President Conde.

"It's tarnishing the image of Guinea... You have to ask yourself the question: who is benefitting from these deaths?"

'Axis of democracy'

Wanindara's history is deeply entwined with resentment toward the state.

Founded in the late 1970s as a concession to soldiers -- when the area was still verdant bush -- settlers moved in following the construction of a highway known as "Route le Prince", or the Prince's road.

Waves of Fulani people, also called Peul, then moved to Wanindara in 1998 after the authorities razed a nearby district, according to local government official Abou Bangoura.

The perceived injustice of the event still haunts popular memory.

Wanindara tranformed into a hotbed of anti-government activity under the former authoritarian leader Lansana Conte, political scientist Kabinet Fofana said.

It, and surrounding areas, became known as the "axis of democracy". To its detractors: "the axis of evil".

Government defiance has continued under Conde.

Huge demonstrations against changing the constitution have flooded Prince's road several times since October, although experts also say government neglect drives protests.

Fofana said political allegiances and poor services may explain opposition more than Wanindara's ethnic makeup.

"These are majority Fulani areas and they are also... forgotten areas," he said.

Guinea's politics are mostly drawn along ethnic lines. President Conde's party is largely backed by Malinke people, for example, and the UFDG by Fulani people, although both insist that they are pluralist.

A fiefdom of bullets

Animosity between residents and security forces has jumped in recent months.

Fatoumata Bah, 27, who was filmed being used by police as an apparent human shield against rock-throwing protesters. By JOHN WESSELS (AFP/File)

Fatoumata Bah, 27, who was filmed being used by police as an apparent human shield against rock-throwing protesters. By JOHN WESSELS (AFP/File)

One widely shared video showed police apparently using a 27-year-old woman as a human shield during a flare-up, provoking outrage. Police later said they arrested the perpetrator.

Last week, a 17-year-old boy was shot dead during unrest in Wanindara.

Bangoura, the local government official, said the neighbourhood's political colours made it a flashpoint. "Every leader has a fiefdom," he said, referring to UFDG leader Cellou Diallo.

Ranking of Guinea on key indicators, compared to neighbouring countries. By (AFP)

Ranking of Guinea on key indicators, compared to neighbouring countries. By (AFP)

Not all the protesters were peaceful, he admitted.

Still, several young residents interviewed by AFP said indiscriminate police violence led them to the streets.

"This is why Wanindara protests," said a 15-year-old boy who declined to be named. "So that the police do not harm our parents".

Camara, the security minister, said there was no evidence security forces had killed anyone and investigations were "systematically opened" following accusations.

He did not exclude the possibility of abuses, but said ascertaining the truth in the febrile political climate is difficult.

Twelve members of the security forces have also been killed, he said, including some by gunfire.

Human rights observers have delivered a withering assessment of the handling of the protests, however.

"Everything points towards the members of the security forces being responsible," said Francois Patuel of Amnesty International, pointing to "countless" eyewitness testimonies.

Dumsor: Mathew Opoku Prempeh has been disrespectful, he should be fired – IES

Dumsor: Mathew Opoku Prempeh has been disrespectful, he should be fired – IES

NPP prioritizing politics over power crisis solution — PR Strategist

NPP prioritizing politics over power crisis solution — PR Strategist

E/R: Gory accidents kills 3 persons at Aseseaso, several others critically injur...

E/R: Gory accidents kills 3 persons at Aseseaso, several others critically injur...

Nobody can come up with 'dumsor' timetable except Energy Minister – Osafo-Maafo

Nobody can come up with 'dumsor' timetable except Energy Minister – Osafo-Maafo

Dumsor: You ‘the men’ find it difficult to draw timetable when ‘incompetent’ NDC...

Dumsor: You ‘the men’ find it difficult to draw timetable when ‘incompetent’ NDC...

We’re working to restore supply after heavy rains caused outages in parts of Gre...

We’re working to restore supply after heavy rains caused outages in parts of Gre...

NPP government plans to expand rail network to every region — Peter Amewu

NPP government plans to expand rail network to every region — Peter Amewu

Dumsor must stop vigil part 2: We’ll choose how we demonstrate and who to partne...

Dumsor must stop vigil part 2: We’ll choose how we demonstrate and who to partne...

2024 elections: NDC stands on the side of morality, truth; NPP isn't an option —...

2024 elections: NDC stands on the side of morality, truth; NPP isn't an option —...

Akufo-Addo has moved Ghana from 'Beyond Aid' to ‘Beyond Borrowing’ — Haruna Idri...

Akufo-Addo has moved Ghana from 'Beyond Aid' to ‘Beyond Borrowing’ — Haruna Idri...