East Africa continues to battle a locust invasion with Uganda scrambling to respond to the latest arrivals. In nearby Ethiopia, one of the frontline countries, swarms of such magnitude have not been seen in more than 60 years. Since then, the country has rolled out a defence system to limit the damage.

“We get plastic bottles, we put stones in them and shake them and hit metal containers. We also scare them away with fires,” Amina Mohamed says on her small farm in the lowlands of Ethiopia's Dire Dawa region.

The farm was hit hard by the locusts. She and her family mostly warded them off, but much of her young sorghum – a popular grain in the country – was destroyed.

East Africa is in the midst of one its worst locust invasions in over 20 years.

Warm temperatures brought on cyclones from the Indian Ocean, which led to high rainfall on the Arabian Peninsula, specifically around Yemen, Oman and Saudi Arabia – optimal conditions for locusts.

Swarms are an annual occurrence, with the insects usually entering Ethiopia from Yemen, Somaliland or Somalia.

But this event is "exceptional", says Zebdewos Salato, the planned protection director at Ethiopia's Ministry of Agriculture.

"From June 2018, there were huge migration swarms in both directions – one in the northeast of Ethiopia, crossing Djibouti, and the other directly from Somaliland,” Salato explains.

What drives the locust?

Locusts, or hoppers as they're sometimes called, need specific conditions to really thrive: rain, moderate temperatures, moist soil and green vegetation.

The insect in itself is not harmful. But when breeding in favourable conditions, locusts begin to look for food in the fledgling phase – as soon as they grow wings – which is when swarms start gathering momentum.

“Somalia is not like Ethiopia. It's mostly desert. The coastal areas are favourable for breeding. So once they feed on trees there, they move to Ethiopia,” explains Hiwot Belihu, the base manager of the Desert Locust Control organisation in Dire Dawa.

Minimal damage

Amina Mohamed's fields appear bare as they stretch out to the nearby hills. She knows all too well what happens when locusts come in their swarms of hundreds of millions.

Not far from Mohamed is the farm of Ifto Adem Moussa.

“It was was like a fog, I couldn't count them, there were so many,” she tells me as she points to the stubs of sorghum on her field.

Both women cut the remaining stems down to sell as kindling.

Moussa also tried to scare-off the approaching locusts.

“We brought tires from the cars to burn, to make a thick smoke to force them away. We also put sand on the fire, we added different dry plants as well to increase the smoke to push them away.

In both cases, the sorghum crops were still at the milky stage, and so very appealing to locusts. Another month mature and the hoppers wouldn't have looked twice at the sorghum which would normally be about two metres in height.

But while their crops were devastated, the damage incurred across these locust-prone regions is generally considered minimal – thanks to the defence system in place.

Triple threat

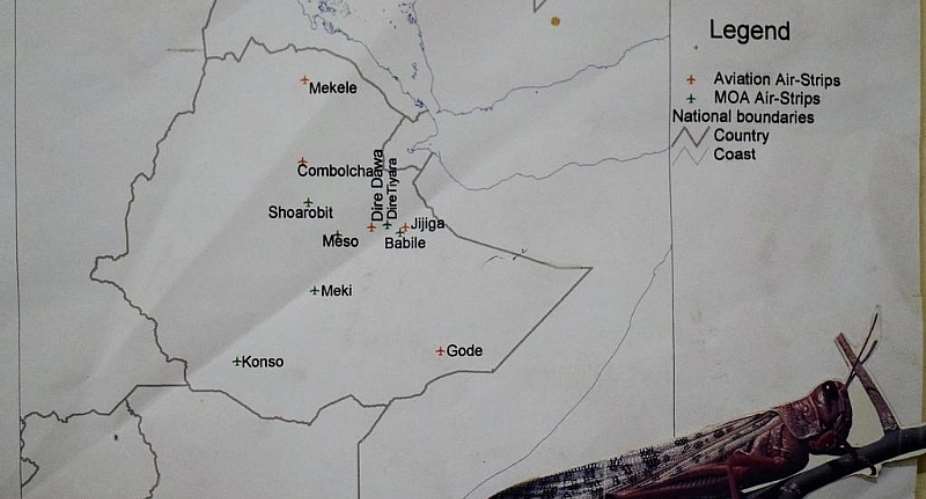

The capital Addis Ababa feels far from the locust crisis. But it's the hub for the country's locust activity surveillance and defence operations.

At the national and regional level, much of that is done through the Ministry of Agriculture, with Zebdewos Salato, followed by coordination with FAO-Ethiopia and FAO-Rome's Desert Locust Watch programme, and the Desert Locust Control organisation.

When advance warning of a pending invasion is received through surveillance within and without the country, the Ministry of Agriculture jumps into action.

“We have scouts...volunteer groups from the community, who share information in those frontline regions. We also have community elders and religious leaders who give information which immediately reaches us,” explains Salato.

Options to kill

The next step involves two options: aerial or mechanical operations.

Aerial eradication is reserved for the largest swarms, which can be seen from a distance, with planes spraying pesticides over them.

“The desert locust is a migratory pest. When it reproduces it hops around in huge bands. That requires ground application of pesticides in order to kill them at their breeding sites. After they form swarms, you can only control them using pesticides,” says Dr Mulatu Bayeh, an entomologist and Integrated Pest Management expert at the UN's Food and Agriculture Organization, based in Addis Ababa.

Mechanical operations are deployed against small swarms, or when the locusts are still at breeding stage.

Salato says mechanical methods can involve spraying pesticides from a backpack or by killing them individually – a far less effective method.

The three experts say the current invasion would have been minimised if Somalia had been able to wipe out the locusts in the breeding stage, while on its territory.

But Somalia doesn't carry out regular surveys and doesn't share reports with neighbouring countries. It is also worried about pesticides harming cattle and crops, which means locust swarms are left free to breed and move on to countries like Ethiopia, according to Zabdewos and Mulatu.

This story was produced for the Spotlight on Africa podcast.

NDC demands complete overhaul of security protocols at EC to safeguard electoral...

NDC demands complete overhaul of security protocols at EC to safeguard electoral...

Ghana reaches interim deal with international bondholders — Finance Ministry

Ghana reaches interim deal with international bondholders — Finance Ministry

Mahama to form joint army-police anti-robbery squads to safeguard 24-hour econom...

Mahama to form joint army-police anti-robbery squads to safeguard 24-hour econom...

Another man jailed eight months over shrinking penis

Another man jailed eight months over shrinking penis

Ghana to adjust external bond deal to meet IMF debt sustainability goals — Finan...

Ghana to adjust external bond deal to meet IMF debt sustainability goals — Finan...

IMF negotiations: We've not failed to reach an agreement with bondholders; we’ve...

IMF negotiations: We've not failed to reach an agreement with bondholders; we’ve...

EC begins recruitment of temporary electoral officials, closes on April 29

EC begins recruitment of temporary electoral officials, closes on April 29

NPP lost the 2024 elections in 2022 due to inflation and cedi depreciation — Mar...

NPP lost the 2024 elections in 2022 due to inflation and cedi depreciation — Mar...

Your good heart towards Ghana has changed; don’t behave like Saul - Owusu Bempah...

Your good heart towards Ghana has changed; don’t behave like Saul - Owusu Bempah...

Wa West: NDC organizes symposium for Vieri Ward Women

Wa West: NDC organizes symposium for Vieri Ward Women