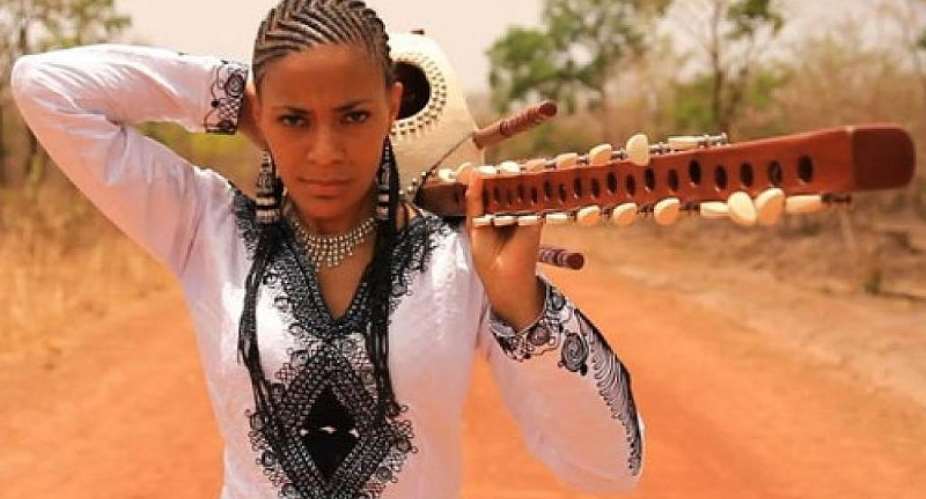

Sona Jobarteh comes from a long West African tradition of Griots and kora players from Mali and The Gambia. She's become one of the rare women in the world to master the 24-string instrument which is traditionally reserved to men. She talks to RFI about working within the tradition to be better able to expand it.

Sona Jobarteh's grandfather was Amadu Bansang Jobarteh, an oral historian and hereditary praise singer from the Mandinka people of The Gambia. Her cousin is Mali's Toumani Diabaté. Her brother began teaching her to play the kora when she was just three, but when she decided she wanted to make a career out of it, she turned to her father Sanjally Jobarteh.

"I always had a very natural connection with the older repertoire," Jobarteh explains as we sit at her hotel before a concert in Paris's New Morning early November. "That's why I really wanted to study with my father because he is very much an expert in that style of playing."

Her father was a demanding task-master.

"He told me that he will teach me as his child, not as his daughter, not as his son but as his child which is no gender. And also he told me that the one thing he wanted in return for teaching me is that I aim to be just a good kora player not a good female kora player."

"He said if someone listens to you they shouldn't be able to say it's a girl or it's a boy it's just a good kora player."

Jobarteh has gone on to become a very successful and respected kora player, vocalist and instrumentalist, demonstrating to her own and fuutre generations that "you don't have to conform to outside influence to be successful in the music industry. You can actually represent your tradition, you can even sing in your own language without having to bend to pressure not to do so."

She did just that in 2011, sinigng in Mandekan on her album Fasiya.

"Fasiya was all about my heritage and I saw it as a risk or a challenge because I'm no longer singing in English, I'm no longer playing any European instruments, and it's traditional.

"I was not sure if I would get any audience, but I made the conscious decision to prefer to do what means something to me and have very few people follow than try to conform to something that is not true to me and be popular."

Her gamble paid off. But she hasn't released another album since, putting all her energies, and finances, into the Gambia Academy of Music and Culture she returned to The Gambia to open in 2015.

The school educates children in their cultural traditions and heritage alongside the mainstream curriculum.

She says it's important to "demonstrate the worth of what they have rather than what they don't have," so that they remain in the country rather than believing that "hope, the future and everything lies outside their country".

"The academy is actually everything I do," she continues, "and in many ways the music increasingly is now just a means for me to be able to support and to spread awareness about what I'm trying to do in The Gambia."

Music in this week's programme is from Jobarteh's 2011 album Fasiya. Her upcoming album will focus on the future: social activism, education, women and raising awareness of the challenges her country is facing.

Follow Sona Jobarteh on facebook

We’ll no longer tolerate your empty, unwarranted attacks – TUC blasts Prof Adei

We’ll no longer tolerate your empty, unwarranted attacks – TUC blasts Prof Adei

Bawumia donates GHc200,000 to support Madina fire victims

Bawumia donates GHc200,000 to support Madina fire victims

IMF to disburse US$360million third tranche to Ghana without creditors MoU

IMF to disburse US$360million third tranche to Ghana without creditors MoU

Truck owner share insights into train collision incident

Truck owner share insights into train collision incident

Paramount chief of Bassare Traditional Area passes on

Paramount chief of Bassare Traditional Area passes on

Two teachers in court over alleged illegal possession of BECE papers

Two teachers in court over alleged illegal possession of BECE papers

Sunyani: Victim allegedly shot by traditional warriors appeals for justice

Sunyani: Victim allegedly shot by traditional warriors appeals for justice

Mahama vows to scrap teacher licensure exams, review Free SHS policy

Mahama vows to scrap teacher licensure exams, review Free SHS policy

Government will replace burnt Madina shops with a new three-story, 120-store fac...

Government will replace burnt Madina shops with a new three-story, 120-store fac...