The second-largest Ebola epidemic continues in North Kivu, DRC, as health responders continue to battle the disease. The outbreak has raged for more than a year, but numbers have begun dropping as those at its epicentre begin to feel more confident about how to deal with the virus.

In Part 3 of RFI's focus on issues surrounding the Ebola crisis, Laura Angela Bagnetto speaks to experts in the region about how cultural misunderstandings and miscommunication affected the Ebola response in the North Kivu.

The challenge of North Kivu is that it is linguistically diverse French and Kiswahili are two official languages spoken in the region, along with Kinande, a local language. When the Ebola epidemic hit the region in August 2018, an emergency response was mobilised with Francophone speakers – either from the African continent or Western countries.

With the danger and severity of the outbreak, less attention was paid “to make sure that the information actually being shared on how to prevent Ebola, and how to treat and cure the disease, in a language that people could actually understand”, says Mia Marzotto of Translators Without Borders, a group that aims to close the language gaps that hinder humanitarian efforts worldwide.

North Kivu is a restive region containing some 70 different armed militias, in an environment where large portions of the population, particularly women and old people, have not had the opportunities to study French, making the a language literally out of reach for many in the region.

And while Kiswahili was the second language responders used for posters and information campaigns, it is not standardised Kiswahili, but changes from city to city, town to town, says Marzotto, speaking to RFI in Goma, DRC.

“Health centre, or centre de santé in French is kituoa kya afia in Congolese Swahili, and ku dawa in local Swahili in Beni,” she says, giving one example.

And if that complicates issues, Kinande also contains hyper-local variations. Only 44 kilometres separates the town of Beni and the city of Butembo.

“Medical check-up is erilevya muviri in Kinande in Beni, and erisuvakolania ovulwere in Kinande in Butembo,” she adds.

Lost in translation

While some variation of Kinande eventually became the go-to language for the local response, health workers in the region created specialised medical terms that had never been used in a health context before. The terms were created for health workers and communications staff to educate people on the deadly disease, such as cas suspect in French, that is a suspected case of Ebola.

“The word cas in Kinande spoken in Beni is a diminutive. So when people hear cas, you're diminishing them,” says Marzotto, which creates confusion and negative connotations.

The term vainqueur, or 'winner' in French, is given to people who have been cured of Ebola. Translators Without Borders finds this term problematic, too.

“In people's minds they associated this with conflict or some kind of violence that they won,” says Marzotto.

“One thing that we heard from people we spoke to in Beni in our recent language assessment is that using this term vainqueur is as if saying somebody suspected -- a police term-- of having Ebola was brought to the treatment centre where he had a fight with the doctor and won,” she adds.

The term health officials use for the strategy of vaccinating people who have come into contact with an Ebola sufferer is 'ring de vaccination', or vaccination ring, a word in French borrowed from English.

Marzotto says that when they carried out their research in Beni, one of the Ebola hotspots in North Kivu, local people thought of this as a boxing ring. “Vaccination is linked to some violent conflict or confrontation between two people or more, and not necessarily as something that can protect you and make sure that you and your family can be safe,” she says.

'Westerners don't care about Congolese'

The communication divide in understanding exactly what Ebola is and how it can be transmitted only heightened with the arrival of foreigners for the health response, where mistrust of outsiders only adds to the perception the region has been largely forgotten by the international community.

According to the Kivu Security Tracker website, some 822 incidents perpetrated by armed militias in North Kivu since April 2017 have resulted in 1,589 violent deaths. The site, run jointly by New York University and Human Rights Watch, maps violence by state security forces and armed groups in the eastern DRC.

Civil society leaders from the group Forces vives du Nord-Kivu point out that at least 2850 people have been massacred by the rebel Ugandan Allied Democratic Forces (ADF) since they began terrorising the region in 2014.

“I've met some people who ask, why, when there are massacres in Beni, the international community doesn't know how to react. But when there's Ebola, all the community is mobilised, and today, the sickness has become international news,” says Merveille Saliboko, a Butembo-based blogger with Habari RDC, a news site that tackles misinformation and dispels rumours by fact-checking comments made about Ebola on social media.

Although Butembo is a big city in North Kivu with a population of one million, it is known for trade, not aid, says Saliboko. When the Ebola response began, more trucks and 4x4s were seen on its dirt roads than ever before. While the international health response mobilised, locals were initially cut out of the equation, creating resentment.

Attacks on medical staff and Ebola clinics and the misunderstandings through language forced people running the Ebola response to use another tack employing locals, including civil society, to transmit the message and inform people.

'Ebola Business'

“There's these [local] people who are part of the medical response, who yesterday couldn't buy a beer, and now, they are buying beers, and people see this and think, this is dirty money,” says Saliboko.

The perception of making money off people's pain angered many in the region, who struggle to put food on the table. Miscommunication again fuelled the 'Ebola business' scenario, according to feedback Translators Without Borders gathered on the Ebola posters dotted around the region.

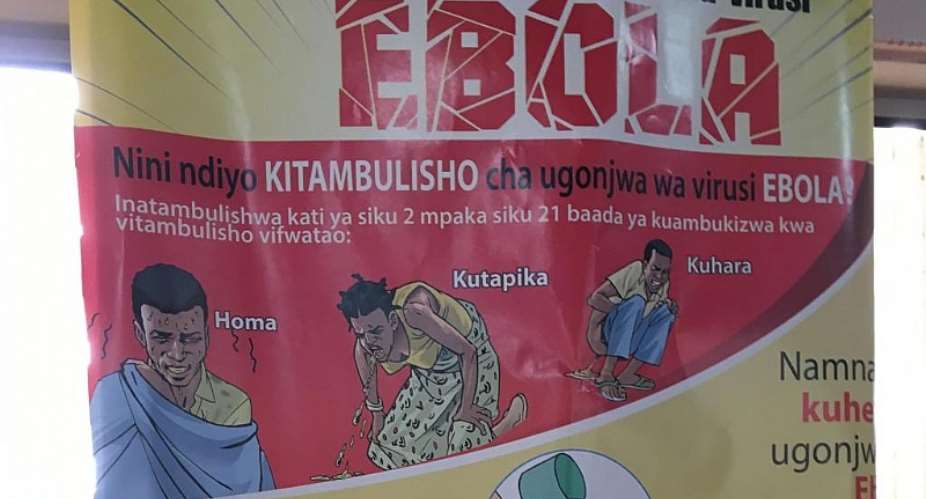

Some of the posters, with Ebola written in red at the top, depicted the various symptoms of Ebola: vomiting and bloody diarrhoea. Sources of Ebola, including touching dead animals, touching a corpse, touching the clothes of someone who had recently died of Ebola were also shown, with a bright red 'X' to indicate that this was a negative behaviour.

“Red is associated with blood, and of course, this is not present in all Ebola symptoms. There's blood involved, but there are dry symptoms as well or where blood wouldn't be seen, so that already was creating some confusion,” says Marzotto.

The background of these posters were yellow, for no particular reason, says Marzotto.

“People associate yellow with wealth or with money. So when this combination of red and yellow comes together, people told us that, to them, this means Ebola Business. That means the money that is behind the outbreak and the deaths of a lot of people, so of course it is something that hurts and is not necessarily understood in the way that we think it would be understood,” she adds.

Organ snatching and other cultural miscommunication

Communication confusion in Butembo and Beni, resentment and anger culminated in a number of attacks on healthcare centres and on medical personnel as well, including the murder of Cameroonian Doctor Richard Valery Mouzoko Kiboung in April.

Cultural considerations play a role in the reaction by some. Part of the Red Cross' remit includes handling burials during Ebola time, or otherwise. While normally a difficult job, especially when picking up and burying bodies after a militia attack, the level of danger encountered reached new heights after the Ebola outbreak began.

Three Congo Red Cross Ebola burial attendants were brutally attacked in October 2018 in Butembo while carrying out a burial.

According to Kizito Mbusa, Congolese Red Cross head in Butembo, locals initially did not understand why certain procedures had to be carried out to ensure a safe burial for Ebola victims, including putting the corpse in a body bag and then placing the body bag in a coffin for burial all while wearing protective gear and bleach, to disinfect the area.

“Everything that we use, our way of working, is nearly the same when we operate in a conflict zone,” says Mbusa, referring to the regular armed militia attacks in the area. “We use body bags and bleach, but when there's an attack, local communities are trying to flee, so they don't see what we do,” he adds.

In an effort to make local communities feel at ease, Red Cross volunteers went in to local communities to show exactly how they operate in order to dispel the numerous rumours around Ebola burial. Locals were up in arms after witnessing Red Cross workers place a swab in the dead person's mouth who was suspected to have died from Ebola. People thought the process of taking a sample of their saliva for testing was a way to extract their organs through their mouth.

“When we demonstrate to the community what we do and why we do it, they begin to understand. Before, they said, 'Everything you do when you put that in the dead person's mouth is to take out their tongue!' That's what they thought,” he adds.

Paying attention to cultural sensitivity and local feedback helped create a better atmosphere around the custom of burials.

“We received feedback saying that the family must be present when the corpse is put into the body bag, so we accommodated this,” says Mbusa. Local burial customs for the Nande people also include family members touching the corpse of their loved one, a practice that hastened the spread of Ebola in the area. Although locals were upset that they had to change certain cultural behaviours, Mbusa and the Red Cross team worked with the communities so everyone understood the reasoning behind the practice.

A compromise included Red Cross workers in full gear “opening the body bag so family members can see their face,” says Mbusa. They also left the body bag slightly unzipped at the head, so the dead person could communicate with their ancestors once they were buried.

Other Nande burial customs had to be modified. Women who die with braids in their hair are required to have their heads shaved before burials, but the Red Cross stressed that this practice could transmit Ebola.

For pregnant women who died of Ebola, other modifications were necessary. According to Nande custom, two people cannot be buried in the same coffin. Normally the foetus would be surgically removed and placed in a separate casket, but this rite could transmit Ebola. Family members or the chief must be paid a fine in order to allow the woman and foetus to be buried together.

“We heard that the community didn't understand what Ebola is, and initially we came without speaking to the community,” says Mbusa, which caused some attacks and initial community resentment. “But we went back to the community to say, 'what do you want us to stop? What's working?' and the community explained the difficulties and worries they had,” says Mbusa.

The Ebola epidemic has lasted more than a year in North Kivu, causing a number of adjustments for the local communities and with the Ebola health response teams. The initial lack of communication was surely a conduit for larger problems, according to Translators Without Borders.

“There's been a lot of effort on community engagement as a key pillar in the response plan, but at the same time, some of the linguistic dynamics remain,” says TWB's Marzotto.

“Some of the key gaps in terms of people actually understanding the information, health teams having access to information that is timely... in the health response overall, there is still quite a gap,” she adds.

We’ll protect state wealth from opaque deals – Prof Jane Naana

We’ll protect state wealth from opaque deals – Prof Jane Naana

Mauritania president says running for second term in June polls

Mauritania president says running for second term in June polls

I won't ever say I was a mere driver’s mate' — Prof. Opoku-Agyemang

I won't ever say I was a mere driver’s mate' — Prof. Opoku-Agyemang

2024 polls: 'EC struggling to defend credibility'— Prof. Opoku-Agyemang

2024 polls: 'EC struggling to defend credibility'— Prof. Opoku-Agyemang

Akufo-Addo gov't's 'greed, unbridled arrogance, unrestrained impunity, sheer dis...

Akufo-Addo gov't's 'greed, unbridled arrogance, unrestrained impunity, sheer dis...

Election 2024: Ghana needs an urgent reset, a leadership that is inspiring – Ma...

Election 2024: Ghana needs an urgent reset, a leadership that is inspiring – Ma...

Partner NDC to rollout a future of limitless prospects – Prof Jane Naana Opoku-A...

Partner NDC to rollout a future of limitless prospects – Prof Jane Naana Opoku-A...

NPP will remain in gov’t till Jesus comes — Diana Asamoah

NPP will remain in gov’t till Jesus comes — Diana Asamoah

Sunyani Technical University demands apology from former SRC president over sex-...

Sunyani Technical University demands apology from former SRC president over sex-...

'Dumsor' was resolved by Mahama but ‘incompetent' Akufo-Addo has destroyed the g...

'Dumsor' was resolved by Mahama but ‘incompetent' Akufo-Addo has destroyed the g...